Cell proliferation is an essential process with the key role of maintaining the life of an organism through the healing of wounds, developing the organs and regenerating the tissues. Stem cells are a particular type of cells that have two important properties: self-renewal and developing into different specialized functional cells. According to their potential to differentiate, there are three types of stem cells: totipotent (TSCs), pluripotent (PSCs) and multipotent (MPSCs). Various cellular behaviors such as adhesion, migration, differentiation, cytoskeleton distortion or even gene expression were shown earlier to clearly depend on the changes in surface topography.

- cell differentiation

- surface topography

- fibronectin

1. The Impact of the Surface Topography on Cell Proliferation

| Lithography | Patterned Material | Resulting Pattern | Pattern Dimension | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLW | chitosan, starch | pores | μm size | [30] |

| UV light | silk protein | non-spherical particles | several μm | [31] |

| UV light | wool keratin protein | lines circular patterns crosses triangles |

2 μm/width 3 μm/diameter 3 μm/width tens of μm |

[32] |

| EBL | sugar-based polymer | moth-eye patterns | 120 nm/period | [33] |

| EBL | biotinylated PEG | pads | ~10 μm | [34] |

| IBL | DNA oligonucleotides neutravidin anti-mouse IgG |

line assays complex stripes-based patterns |

1–2 μm/width down to 100 nm/width |

[35] |

| NIL | chitosan | lines circular pillars |

10 μm/width 500 nm/diameter |

[6] [36] |

| NIL | proteins | lines | 700 nm/period | [37] |

| NIL | gelatins/genipin | grooves holes pillars |

500 nm/width 500 nm/diameter 100 nm/diameter |

[38] |

| NIL | cellulose | holes lines square pillars rhombus pillars holes |

400 nm/diameter 140 nm/width 1 μm/diameter 600 nm/width 600 nm/diameter |

[39] [40] |

| μCP | protein/Sylgard 527 | arrays of nanodots | 200 nm × 200 nm | [41] |

| μCP | biomolecules/poly(4-aminostyrene) | stripes pads |

~2 μm/width ~7 μm/diameter |

[42] |

| μCP | silk | lines | hundreds of μm/width | [43] |

| μCP | neutravidin/biotin | arrays of nanodots | ~62 nm/diameter | [44] |

| μCP | amyloid | spider web arrays | hundreds of μm/width | [6] |

| TCSPL | enzyme | rectangles squares lines dots |

4.5 μm × 1.5 μm 100 nm ×100 nm 8–9 nm/width 8 nm/diameter |

[45] |

| PL | streptavidin | patches | 15 nm/diameter | [46] |

| DNSA | DNA | squares disks five-point stars rectangles triangles |

~100 nm/diameter ~100 nm/diameter ~100 nm/diameter ~100 nm/diameter ~100 nm/diameter |

[47] |

2. The Impact of the Surface Topography on Cell Differentiation

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23147731

References

- Yang, C.-Y.; Huang, W.-Y.; Chen, L.-H.; Liang, N.-W.; Wang, H.-C.; Lu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.-W. Neural Tissue Engineering: The Influence of Scaffold Surface Topography and Extracellular Matrix Microenvironment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 567–584.

- Rangappa, N.; Romero, A.; Nelson, K.D.; Eberhart, R.C.; Smith, G.M. Laminin-Coated Poly(L-Lactide) Filaments Induce Robust Neurite Growth While Providing Directional Orientation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 625–634.

- Inzana, J.A.; Olvera, D.; Fuller, S.M.; Kelly, J.P.; Graeve, O.A.; Schwarz, E.M.; Kates, S.L.; Awad, H.A. 3D Printing of Composite Calcium Phosphate and Collagen Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4026–4034.

- Simitzi, C.; Efstathopoulos, P.; Kourgiantaki, A.; Ranella, A.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Fotakis, C.; Athanassakis, I.; Stratakis, E.; Gravanis, A. Laser Fabricated Discontinuous Anisotropic Microconical Substrates as a New Model Scaffold to Control the Directionality of Neuronal Network Outgrowth. Biomaterials 2015, 67, 115–128.

- Antmen, E.; Ermis, M.; Demirci, U.; Hasirci, V. Engineered Natural and Synthetic Polymer Surfaces Induce Nuclear Deformation in Osteosarcoma Cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part. B Appl. Biomater. 2019, 107, 366–376.

- Li, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Cui, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Anisotropic Ridge/Groove Microstructure for Regulating Morphology and Biological Function of Schwann Cells. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100468.

- Vrana, N.E.; Elsheikh, A.; Builles, N.; Damour, O.; Hasirci, V. Effect of Human Corneal Keratocytes and Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells on the Mechanical Properties of Micropatterned Collagen Films. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4303–4310.

- Gil, E.S.; Park, S.-H.; Marchant, J.; Omenetto, F.; Kaplan, D.L. Response of Human Corneal Fibroblasts on Silk Film Surface Patterns. Macromol. Biosci. 2010, 10, 664–673.

- Li, N.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y.; Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Zhang, F.; Gu, N. Effect of Surface Topography and Bioactive Properties on Early Adhesion and Growth Behavior of Mouse Preosteoblast MC3T3-E1 Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 17134–17143.

- Nagata, I.; Kawana, A.; Nakatsuji, N. Perpendicular Contact Guidance of CNS Neuroblasts on Artificial Microstructures. Development 1993, 117, 401–408.

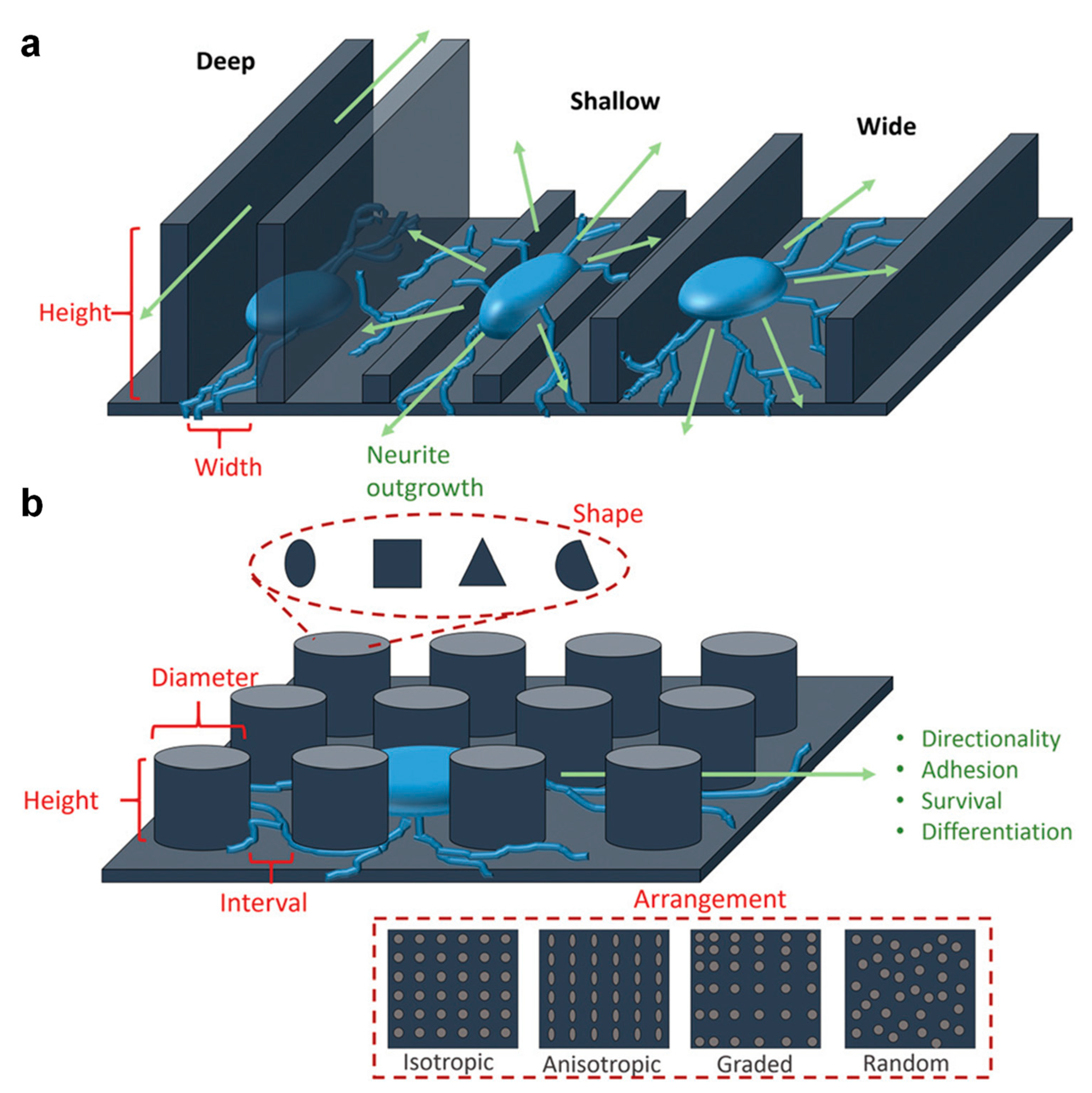

- Simitzi, C.; Ranella, A.; Stratakis, E. Controlling the Morphology and Outgrowth of Nerve and Neuroglial Cells: The Effect of Surface Topography. Acta. Biomater. 2017, 51, 21–52.

- Schmalenberg, K.E.; Uhrich, K.E. Micropatterned Polymer Substrates Control Alignment of Proliferating Schwann Cells to Direct Neuronal Regeneration. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 1423–1430.

- Miller, C.; Jeftinija, S.; Mallapragada, S. Micropatterned Schwann Cell–Seeded Biodegradable Polymer Substrates Significantly Enhance Neurite Alignment and Outgrowth. Tissue Eng. 2001, 7, 705–715.

- Wen, X.; Tresco, P.A. Effect of Filament Diameter and Extracellular Matrix Molecule Precoating on Neurite Outgrowth and Schwann Cell Behavior on Multifilament Entubulation Bridging Devicein Vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 76A, 626–637.

- Hsu, S.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lu, P.S.; Lai, C.-S.; Chen, C.-J. Oriented Schwann Cell Growth on Microgrooved Surfaces. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 92, 579–588.

- Vleggeert-Lankamp, C.L.A.M.; Pêgo, A.P.; Lakke, E.A.J.F.; Deenen, M.; Marani, E.; Thomeer, R.T.W.M. Adhesion and Proliferation of Human Schwann Cells on Adhesive Coatings. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2741–2751.

- Li, W.; Tang, Q.Y.; Jadhav, A.D.; Narang, A.; Qian, W.X.; Shi, P.; Pang, S.W. Large-Scale Topographical Screen for Investigation of Physical Neural-Guidance Cues. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8644.

- Zhong, C. Industrial-Scale Production and Applications of Bacterial Cellulose. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 605374.

- Bottan, S.; Robotti, F.; Jayathissa, P.; Hegglin, A.; Bahamonde, N.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Bayer, I.S.; Scarpellini, A.; Merker, H.; Lindenblatt, N.; et al. Surface-Structured Bacterial Cellulose with Guided Assembly-Based Biolithography (GAB). ACS Nano 2015, 9, 206–219.

- Anderson, J.M.; Rodriguez, A.; Chang, D.T. Foreign Body Reaction to Biomaterials. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 86–100.

- Robotti, F.; Bottan, S.; Fraschetti, F.; Mallone, A.; Pellegrini, G.; Lindenblatt, N.; Starck, C.; Falk, V.; Poulikakos, D.; Ferrari, A. A Micron-Scale Surface Topography Design Reducing Cell Adhesion to Implanted Materials. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10887.

- Ber, S.; Torun Köse, G.; Hasırcı, V. Bone Tissue Engineering on Patterned Collagen Films: An in Vitro Study. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 1977–1986.

- Murphy, C.M.; Haugh, M.G.; O’Brien, F.J. The Effect of Mean Pore Size on Cell Attachment, Proliferation and Migration in Collagen–Glycosaminoglycan Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 461–466.

- Anselme, K. Osteoblast Adhesion on Biomaterials. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 667–681.

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gu, X. The Interaction of Schwann Cells with Chitosan Membranes and Fibers in Vitro. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 4273–4278.

- Li, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Jiang, M.; Gu, X.; Yang, Y. Porous Chitosan Scaffolds with Surface Micropatterning and Inner Porosity and Their Effects on Schwann Cells. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 8503–8513.

- Gnavi, S.; Fornasari, B.; Tonda-Turo, C.; Laurano, R.; Zanetti, M.; Ciardelli, G.; Geuna, S. The Effect of Electrospun Gelatin Fibers Alignment on Schwann Cell and Axon Behavior and Organization in the Perspective of Artificial Nerve Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 12925–12942.

- Kalinina, S.; Gliemann, H.; López-García, M.; Petershans, A.; Auernheimer, J.; Schimmel, T.; Bruns, M.; Schambony, A.; Kessler, H.; Wedlich, D. Isothiocyanate-Functionalized RGD Peptides for Tailoring Cell-Adhesive Surface Patterns. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3004–3013.

- binte, M.; Yusoff, N.Z.; Riau, A.K.; Yam, G.H.F.; binte Halim, N.S.H.; Mehta, J.S. Isolation and Propagation of Human Corneal Stromal Keratocytes for Tissue Engineering and Cell Therapy. Cells 2022, 11, 178.

- Castillejo, M.; Rebollar, E.; Oujja, M.; Sanz, M.; Selimis, A.; Sigletou, M.; Psycharakis, S.; Ranella, A.; Fotakis, C. Fabrication of Porous Biopolymer Substrates for Cell Growth by UV Laser: The Role of Pulse Duration. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 8919–8927.

- Pal, R.K.; Kurland, N.E.; Jiang, C.; Kundu, S.C.; Zhang, N.; Yadavalli, V.K. Fabrication of Precise Shape-Defined Particles of Silk Proteins Using Photolithography. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 85, 421–430.

- Zhu, S.; Zeng, W.; Meng, Z.; Luo, W.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, C.; Huang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X.Y. Using Wool Keratin as a Basic Resist Material to Fabricate Precise Protein Patterns. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1900870.

- Takei, S.; Oshima, A.; Oyama, T.G.; Ito, K.; Sugahara, K.; Kashiwakura, M.; Kozawa, T.; Tagawa, S. Organic Solvent-Free Sugar-Based Transparency Nanopatterning Material Derived from Biomass for Eco-Friendly Optical Biochips Using Green Lithography. In Biophotonics: Photonic Solutions for Better Health Care IV; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; p. 912917.

- Rusen, L.; Cazan, M.; Mustaciosu, C.; Filipescu, M.; Sandel, S.; Zamfirescu, M.; Dinca, V.; Dinescu, M. Tailored Topography Control of Biopolymer Surfaces by Ultrafast Lasers for Cell–Substrate Studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 302, 256–261.

- Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Mak, W.C.; Trau, D. Integrated Direct DNA/Protein Patterning and Microfabrication by Focused Ion Beam Milling. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 1636–1643.

- Heedy, S.; Pineda, J.J.; Meli, V.S.; Wang, S.-W.; Yee, A.F. Nanopillar Templating Augments the Stiffness and Strength in Biopolymer Films. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3311–3322.

- Sanchez-deAlcazar, D.; Romera, D.; Castro-Smirnov, J.; Sousaraei, A.; Casado, S.; Espasa, A.; Morant-Miñana, M.C.; Hernandez, J.J.; Rodríguez, I.; Costa, R.D.; et al. Engineered Protein-Based Functional Nanopatterned Materials for Bio-Optical Devices. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 3980–3991.

- Makita, R.; Akasaka, T.; Tamagawa, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Miyata, S.; Miyaji, H.; Sugaya, T. Preparation of Micro/Nanopatterned Gelatins Crosslinked with Genipin for Biocompatible Dental Implants. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 1735–1754.

- Espinha, A.; Dore, C.; Matricardi, C.; Alonso, M.I.; Goñi, A.R.; Mihi, A. Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Photonic Architectures by Soft Nanoimprinting Lithography. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 343–348.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Dundar, F.; Carter, K.R.; Watkins, J.J. Fabrication of Patterned Cellulose Film via Solvent-Assisted Soft Nanoimprint Lithography at a Submicron Scale. Cellulose 2018, 25, 5185–5194.

- MacNearney, D.; Mak, B.; Ongo, G.; Kennedy, T.E.; Juncker, D. Nanocontact Printing of Proteins on Physiologically Soft Substrates to Study Cell Haptotaxis. Langmuir 2016, 32, 13525–13533.

- Wang, Z.; Xia, J.; Luo, S.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, T.; Guan, J. Versatile Surface Micropatterning and Functionalization Enabled by Microcontact Printing of Poly(4-Aminostyrene). Langmuir 2014, 30, 13483–13490.

- Ganesh Kumar, B.; Melikov, R.; Mohammadi Aria, M.; Ural Yalcin, A.; Begar, E.; Sadeghi, S.; Guven, K.; Nizamoglu, S. Silk-Based Aqueous Microcontact Printing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 1463–1470.

- Park, S.; Jackman, J.A.; Xu, X.; Weiss, P.S.; Cho, N.-J. Micropatterned Viral Membrane Clusters for Antiviral Drug Evaluation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 13984–13990.

- Liu, X.; Kumar, M.; Calo, A.; Albisetti, E.; Zheng, X.; Manning, K.B.; Elacqua, E.; Weck, M.; Ulijn, R.V.; Riedo, E. Sub-10 Nm Resolution Patterning of Pockets for Enzyme Immobilization with Independent Density and Quasi-3D Topography Control. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 41780–41790.

- Lum, W.; Gautam, D.; Chen, J.; Sagle, L.B. Single Molecule Protein Patterning Using Hole Mask Colloidal Lithography. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 16228–16234.

- Rothemund, P.W.K. Folding DNA to Create Nanoscale Shapes and Patterns. Nature 2006, 440, 297–302.

- Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Fei, Y.; Wu, H.; Ruan, D.; Paul, M.E.; Chen, X.; Yin, Z.; Heng, B.C.; et al. The Relationship between Substrate Topography and Stem Cell Differentiation in the Musculoskeletal System. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 505–521.

- Lanfer, B.; Seib, F.P.; Freudenberg, U.; Stamov, D.; Bley, T.; Bornhäuser, M.; Werner, C. The Growth and Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem and Progenitor Cells Cultured on Aligned Collagen Matrices. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5950–5958.

- Tay, C.Y.; Yu, H.; Pal, M.; Leong, W.S.; Tan, N.S.; Ng, K.W.; Leong, D.T.; Tan, L.P. Micropatterned Matrix Directs Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells towards Myocardial Lineage. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 1159–1168.

- Younesi, M.; Islam, A.; Kishore, V.; Anderson, J.M.; Akkus, O. Tenogenic Induction of Human MSCs by Anisotropically Aligned Collagen Biotextiles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 5762–5770.

- Seo, C.H.; Jeong, H.; Feng, Y.; Montagne, K.; Ushida, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Furukawa, K.S. Micropit Surfaces Designed for Accelerating Osteogenic Differentiation of Murine Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Enhancing Focal Adhesion and Actin Polymerization. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2245–2252.

- Hashemzadeh, H.; Allahverdi, A.; Ghorbani, M.; Soleymani, H.; Kocsis, Á.; Fischer, M.B.; Ertl, P.; Naderi-Manesh, H. Gold Nanowires/Fibrin Nanostructure as Microfluidics Platforms for Enhancing Stem Cell Differentiation: Bio-AFM Study. Micromachines 2019, 11, 50.

- Zhang, C.; Yuan, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, P.; Zhu, T.; Yang, L.; Yin, Z.; Heng, B.C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Well-Aligned Chitosan-Based Ultrafine Fibers Committed Teno-Lineage Differentiation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Achilles Tendon Regeneration. Biomaterials 2015, 53, 716–730.

- Evans, N.D.; Minelli, C.; Gentleman, E.; LaPointe, V.; Patankar, S.N.; Kallivretaki, M.; Chen, X.; Roberts, C.J.; Stevens, M.M. Substrate Stiffness Affects Early Differentiation Events in Embryonic Stem Cells. Eur. Cells Mater. 2009, 18, 1–13.

- Park, J.S.; Chu, J.S.; Tsou, A.D.; Diop, R.; Tang, Z.; Wang, A.; Li, S. The Effect of Matrix Stiffness on the Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Response to TGF-β. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3921–3930.

- Shukla, A.; Slater, J.H.; Culver, J.C.; Dickinson, M.E.; West, J.L. Biomimetic Surface Patterning Promotes Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 21883–21892.

- Metavarayuth, K.; Sitasuwan, P.; Zhao, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Q. Influence of Surface Topographical Cues on the Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Vitro. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 142–151.

- Fedele, C.; Mäntylä, E.; Belardi, B.; Hamkins-Indik, T.; Cavalli, S.; Netti, P.A.; Fletcher, D.A.; Nymark, S.; Priimagi, A.; Ihalainen, T.O. Azobenzene-Based Sinusoidal Surface Topography Drives Focal Adhesion Confinement and Guides Collective Migration of Epithelial Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15329.

- Bhadriraju, K.; Yang, M.; Alom Ruiz, S.; Pirone, D.; Tan, J.; Chen, C.S. Activation of ROCK by RhoA Is Regulated by Cell Adhesion, Shape, and Cytoskeletal Tension. Exp. Cell Res. 2007, 313, 3616–3623.

- Wang, Y.-K.; Yu, X.; Cohen, D.M.; Wozniak, M.A.; Yang, M.T.; Gao, L.; Eyckmans, J.; Chen, C.S. Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2-Induced Signaling and Osteogenesis Is Regulated by Cell Shape, RhoA/ROCK, and Cytoskeletal Tension. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 1176–1186.

- Gu, S.R.; Kang, Y.G.; Shin, J.W.; Shin, J.-W. Simultaneous Engagement of Mechanical Stretching and Surface Pattern Promotes Cardiomyogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 123, 252–258.

- Ding, H.; Zhong, J.; Xu, F.; Song, F.; Yin, M.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, J. Establishment of 3D Culture and Induction of Osteogenic Differentiation of Pre-Osteoblasts Using Wet-Collected Aligned Scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 222–230.