Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Microbiology

The human microbiome encodes more than three million genes, outnumbering human genes by more than 100 times, while microbial cells in the human microbiota outnumber human cells by 10 times. Thus, the human microbiota and related microbiome constitute a vast source for identifying disease biomarkers and therapeutic drug targets.

- biomarkers

- diagnostic biomarkers

- metagenomics

1. Introduction

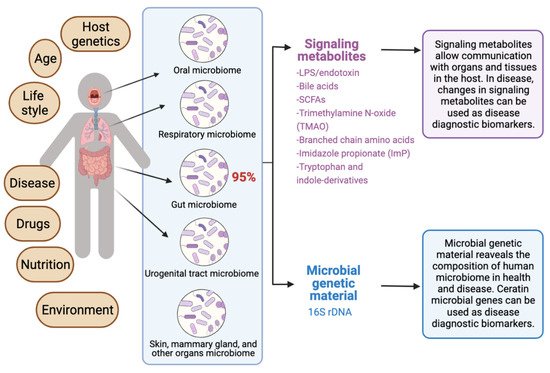

The human microbiota comprises 10–100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells constituting over 10,000 microbial species residing in the human body and outnumbering human cells by 10 times [1]. It consists primarily of bacteria, in addition to viruses, fungi, protozoa, and helminths residing in and on human body organs, such as the skin, mammary glands, mucosa, gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, and urogenital tracts [2,3,4]. The largest percentage of the human microbiota (95%) resides in the GI tract, and every human being has a unique microbiota composition which could potentially serve as a unique fingerprint. The human microbiome consists of the genes of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, and it is often viewed as our “other genome”, which consists of more than three million genes, in comparison with our 23,000 human genes. Hence, the human microbiome has gained increased interest recently with regard to identifying novel drug targets and biomarkers for human disease.

Microbiota affect human health and disease by modulating important metabolic and immunomodulatory processes [3,5]. The interactions between the human body and microbiota form a complex, distinct, and harmonized bionetwork that defines the relationship between the host and its microbiota as commensal, symbiotic, or pathogenic. The human microbiota is continually developing and changing throughout life by responding to host factors such as age, genes, hormonal changes, nutrition, predisposing disease, lifestyle, and many environmental factors [6,7,8,9]. Harmonized microbiota contribute substantially to healthy livelihood [7], while a disruption in microbiota hemostasis (dysbiosis) might contribute to life-threatening diseases [10]. The significant contribution of the human microbiome in health and disease has been recently described in the biomedical literature [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] delineating gastrointestinal [10,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], urinary tract [4,38], and skin [3] microbiota. Evidence from the biomedical literature indicates that alterations in host immunity might be closely related to the compositional and functional changes of gut flora [24,39].

Thus, the human microbiota can potentially lead to the discovery of effective disease diagnostic biomarkers. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), a biomarker is “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” [40]. A diagnostic biomarker is simply a biomarker that “detects or confirms the presence of a disease or condition of interest, or identifies an individual with a subtype of the disease” [41]. The most frequently used biomarkers are derived from either biological materials or imaging data. More recently, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have enabled the identification of highly predictive, disease-specific biomarkers [42].

In fact, microflora disturbances have been linked to many human diseases, including GI tract diseases [10,43], cardiovascular disease [13,44,45], allergies [39,46], inflammation [44,45,47], neuro-disease, stubborn bacterial infections [48,49,50,51], and cancer [37,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Aberrations in the human microbiome are linked to several cancers, including breast, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, and hepatic cancers [69,70]. Additionally, cancer could be provoked by viruses, fungi, helminths, and bacteria [69,70]. Microbiota might also contribute to cancer development by disrupting the balance between the growth and death of host cells after altering the immune system and affecting metabolism [58,71,72]. Furthermore, Microbiota affects cancer prognosis by several mechanisms, including genotoxicity, inflammation, and metabolism [73].

Recent reviews indicated that microbiome signatures can be exploited as disease diagnostic biomarkers [71,72,74,75,76,77,78,79]. Herein, we review the available evidence supporting the use of the human microbiome- and microbiota-derived metabolites for the purposes of disease diagnosis. A graphical summary of the concept in provided in Figure 1. We detail potential microbiota-derived biomarkers for the diagnosis of a variety of diseases, including complex diseases like diabetes, neuro-diseases, and cancer.

Figure 1. Exploiting the human microbiome for diagnostic disease biomarkers.

2. The Rationale for Microbiome-Based Disease Biomarkers

The identification of “ideal biomarkers” is considered a daunting task for many diseases, including some cancer types. Most of the current sampling techniques for cancer tissues cannot identify individuals who will lack response to therapy, and they fall short in classifying cancer types correctly, owing to the inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity of tumors [80]. A biomarker should be easily measurable, non-invasive, and cost-effective. The human microbiome, particularly the gut microbiome, can be considered as a non-invasive approach to identify disease biomarkers that can detect many diseases in the early stages [71,81]. Additionally, the identification of microbiome-based biomarkers can increase the accuracy of disease classification when it is combined with clinical information and other biomarkers. For example, some microbes are known to contribute to the adenoma-carcinoma transition in some cancers, such as colorectal carcer (CRC). Such microbes can be exploited as disease and immunotherapy efficacy biomarkers for CRC [71,81].

In addition to microbiome-based biomarkers, there is also an emerging interest in mast cells (MCs) [82,83,84,85], microRNAs (miRNAs) [86,87], imaging, and machine-learning models [42] as non-invasive disease diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers that promise to shape the future of precision medicine. Sometimes, there is a crosstalk between the human microbiota and other genetic or chemical biomarkers. For example, alterations in fecal small RNA profiles in CRC reflect gut microbiome composition in stool samples [88]. Thus, using multiple connected biomarkers of the network type (i.e., “network biomarkers”) may increase the effectiveness of existing biomarkers.

3. The Significance of Human Microbiota in Health and Disease

The human microbiota plays several important roles in the human body, such as helping in food digestion, producing vitamins, regulating the immune system, and protecting against pathogenic disease-causing microbes. In the following subsections, we review the significance of the human microbiota in health and disease and the importance of classifying healthy microbiomes from unhealthy microbiomes in clinical practice.

3.1. Conservation of Homeostasis

The human microbiota controls the immune system and affects the inflammatory cascade and immune homeostasis in newborn and children [89]. Children developing allergies at advanced ages showed ubiquity of anaerobic bacteria and Bacteroidaceae, as well as a low number of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis [11,27]. Studies reported that these microbes hydrolyze adulterants such as pesticides, plastic particles, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and organic compounds [23]. Further studies revealed that the urinary tract microbiomes detoxify toxins [90]. Studies showed that female genital tract microbiomes provoke an immune response through secreting antimicrobial peptides, inhibitory compounds, and cytokines [90].

3.2. Involvement in Host Immune System

The symbiosis interaction between the indigenous microbiome and the immune system results in the evolution of immune responses and the development of the immune system to recognize pathogens and beneficial microbiota [91,92]. Indeed, the immune system is shaped by the human microbiome [93]. The lack or alterations in the human microbiome might weaken the immune system and induce type II immunity responses and allergies [39,94]. Aberrations of microbiota induce allergic rhinitis in children [39,94]. The gut microbiome activates the regulatory T-cells (Tregs) and proinflammatory Th17cells in the intestine [95,96]. The older neutrophil decreases the proinflammatory properties in vivo [91]. The microbiota induces the growth of neutrophil through MyD88-mediated and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling cascades [91]. Changes in microbial flora decrease the old neutrophils and induce inflammation-mediated tissue injury, such as septic shock and sickle cell disease. Altogether, the microbial flora supervise disease-inducing neutrophil, which is a substantial component in inflammatory diseases [91]. In addition, the gut microbiomes protect the body against harmful pathogens through inducing colonization resistance, as well as synthesizing antimicrobial compounds [97]. A stable intestinal microbiota controls antibodies of CD8+T (killer) and CD4+ (helper) cells that impede the influx of the influenza virus to the respiratory system [89,97]. The gut flora supports and optimizes the functionality of the GIT [98,99]. Activating the regulatory T cells is essential in maintaining the hemostasis of the immune system [89].

3.3. Involvement in Host Nutrition and Metabolism

Gut microbiota provide nutrients to the host by digesting complex dietary elements (e.g., fiber and other complex carbohydrates) in food, permitting their absorption from the gut [100]. Additionally, intestinal microbiota offer essential nutrients that are not available, but are necessary for maintaining GI tract functionality [101]. Furthermore, intestinal microbiota halt cancer prognosis in the GI tract by generating butyrate, which is a product of fermentation complex nutrients [102]. Studies revealed that fruits’ and vegetables’ carbohydrates maintain a healthy GI tract microbiome [97]. In addition, the gut microbiome provide the required vitamins (K and folic acid) for host growth, such as enterobacteria and GI tract bacteria, including Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium species [100]. Moreover, gut microbiota contribute to red and white blood cells (RBC and WBC) synthesis [103]. Live microorganisms (probiotics) are deployed for treating allergic diseases [97]. Probiotics decrease and/or inhibit the activation of T-cells and restrain the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) that participates in systemic inflammation [97]. Gut microbiota produce important vitamins needed for blood coagulation, including B vitamins such as B12, thiamine and riboflavin, and Vitamin K [104,105,106].

3.4. Classifying Healthy and Unhealthy Microbiomes

The identification of microbiome-based biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, risk profiling, and precision medicine relies on the determination of microbial features associated with health or disease. It is often a daunting task to clearly define what constitutes a healthy microbiome in different human populations, especially because a person’s microbiota can be affected by many factors, including age, lifestyle, diet, smoking, exercise, ethnicity, environmental factors, and other factors. Another challenge in classifying healthy versus unhealthy microbiomes stems from limitations in the current technologies and methodologies that do not provide a high microbial resolution on the strain-level, impeding the functional understanding or relevance for health or disease [10].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics12071742

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!