Fertilizer Use Efficiency (FUE) is a measure of the potential of an applied fertilizer to increase its impact on the uptake and utilization of nitrogen (N) present in the soil/plant system. The productivity of N depends on the supply of those nutrients in a well-defined stage of yield formation that are decisive for its uptake and utilization. Traditionally, plant nutritional status is evaluated by using chemical methods. However, nowadays, to correct fertilizer doses, the absorption and reflection of solar radiation is used. Fertilization efficiency can be increased not only by adjusting the fertilizer dose to the plant’s requirements, but also by removing all of the soil factors that constrain nutrient uptake and their transport from soil to root surface. Among them, soil compaction and pH are relatively easy to correct. The goal of new the formulas of N fertilizers is to increase the availability of N by synchronization of its release with the plant demand. The aim of non-nitrogenous fertilizers is to increase the availability of nutrients that control the effectiveness of N present in the soil/plant system. A wide range of actions is required to reduce the amount of N which can pollute ecosystems adjacent to fields.

- crop growth rate

- fertilizer market

- nitrogen use efficiency

- nitrogen gap

1. Fertilizer Use Efficiency—A Real Farming Practice

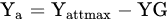

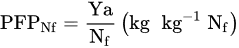

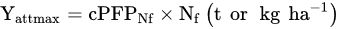

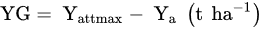

1.1. Nitrogen Gap and the Maximum Attainable Yield

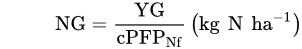

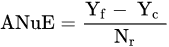

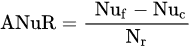

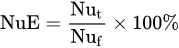

1.2. Fertilizer Use Efficiency—FUE

1.3. Factors Affecting Fertilizer Use Efficiency

2. Soil Factors Affecting FUE

2.1. Soil Texture

2.2. Water Content

2.3. Soil Compaction

2.4. Soil Temperature

2.5. Soil Reaction

2.6. Soil Salinity

2.7. Soil Organic Matter

2.8. Nutrient Shortage

3. FUE—A Message for Agricultural Practice

-

Determine the maximum attainable yield (Yattmax). This is the basis for choosing the most suitable variety for the actual climatic and soil conditions of the farm;

-

Identify soil conditions that constrain:

-

growth and architecture of the root system

-

water and nutrient availability;

-

-

Divide the whole field area into units of homogenous productivity;

-

Identify Nitrogen Hotspots both on the farm and on the specific field;

-

Observe the viability of plants at stages preceding the cardinal phases of yield formation;

-

Schedule the correction of the plant nutritional status during the season to exploit its yield potential.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants11141855

References

- Licker, R.; Johnston, M.; Foley, J.A.; Barford, C.; Kucharik, C.J.; Monfreda, C.; Ramankutty, N. Mind the gap: How do climate and agricultural management explain the ‘yield gap’ of croplands around the world? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 769–782.

- Tandzi, N.L.; Mutengwa, S.C. Factors affecting yields of crops. In Agronomy—Climate Change and Food Security; Amanullah, Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; p. 16.

- Sattari, S.Z.; Van Ittersum, M.K.; Bouwman, A.F.; Smit, A.L.; Janssen, B.H. Crop yield response to soil fertility and N, P, K inputs in different environments: Testing and improving the QEFTS model. Field Crops Res. 2014, 157, 35–46.

- Lollato, R.P.; Edwards, J.T. Maximum attainable wheat yield and resources-use efficiency in the Southern Great Plains. Crop Sci. 2015, 55, 2863–2875.

- Wallace, A.; Wallace, G.A. Closing the Crop-Yield Gap through Better Soil and Better Management; Wallace Laboratories: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003; p. 162.

- Grzebisz, W.; Łukowiak, R.; Sassenrath, G. Virtual nitrogen as a tool for assessment of nitrogen at the field scale. Field Crops Res. 2018, 218, 182–184.

- Dobermann, A.R. Nitrogen use efficiency—State of the art. In Agronomy & Horticulture Faculty Publications, Proceedings of the IFA International Workshop on Enhanced Efficiency Fertilizers, Frankfurt, Germany, 28–30 June 2005; University of Nebraska–Lincoln: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2005; Volume 316, pp. 1–16.

- Grzebisz, W.; Łukowiak, R. Nitrogen Gap Amelioration is a Core for Sustainable Intensification of Agriculture—A Concept. Agronomy 2021, 11, 419.

- Fixen, P.; Brentrup, F.; Bruulsema, T.; Garcia, F.; Norton, R.; Zingore, S. Nutrient/fertilizer use efficiency: Measurement, current situation and trends. In Managing Water and Fertilizer for Sustainable Agricultural Intensification; Drechsel, P., Heffer, P., Magen, H., Mikkelsen, R., Wichelns, D., Eds.; IFA: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 8–38.

- Oenema, O.; Kros, H.; De Vries, W. Approaches and uncertainties in nutrient budgets: Implications for nutrient management and environmental policies. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 20, 3–16.

- Pradhan, P.; Fischer, G.; van Velthuizen, H.; Reusser, D.E.; Kropp, J.P. Closing yield gaps: How sustainable can we be? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129487.

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA; Academic Press: London, UK , 1995; p. 899.

- Parry, A.J.; Andralojc, P.J.; Scales, J.C.; Salvucci, M.E.; Carmo-Silva, A.E.; Alonso, H.; Whitney, S.M. Rubisco activity and regulation as targets for crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 6493, 717–730.

- Guan, P. Dancing with hormones: A current perspective of nitrate signaling and regulation in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1697.

- Luo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, G. How does nitrogen shape plant architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4415–4427.

- Marschner, P. (Ed.) Marchnerr’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012; p. 672.

- Blecharczyk, A.; Zawada, D.; Sawińska, Z.; Małcka-Jankowiak, I.; Waniorek, W. Impact of crop seqeunce and fetilization on yield of winter wheat. Fragm. Agron. 2019, 36, 27–35.

- Tabak, M.; Lepiarczyk, A.; Filipek–Mazur, B.; Lisowska, A. Efficiency of Nitrogen Fertilization of Winter Wheat Depending on Sulfur Fertilization. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1304.

- Roberts, T.L. Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2008, 32, 177–182.

- Zhang, F.; Niu, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Yuan, L.; Xie, J. Potassium nutrition of crops under varied regimes of nitrogen supply. Plant Soil 2010, 335, 21–34.

- Osman, K.T. Soils: Principles, Properties and Management; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 271.

- Kome, G.K.; Enang, R.K.; Tabi, F.O.; Yerima, B.P.K. Influence of Clay Minerals on Some Soil Fertility Attributes: A Review. Open J. Soil Sci. 2019, 9, 155–188.

- Kopittke, P.M.; Menzies, N.W.; Wang, P.; McKenna, B.A.; Lombi, E. Soil and the intensification of agriculture for global food security. Environ. Int. 2019, 132, 105078.

- Merino, C.; Nannipieri, P.; Matus, F. Soil Carbon Controlled by Plant, Microorganism and Mineralogy Interactions. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2015, 15, 321–332.

- Sarkar, B.; Singh, M.; Mandal, S.; Churchman, G.J.; Bolan, N.S. Clay Minerals—Organic Matter Interactions in Relation to Carbon Stabilization in Soils. In The Future of Soil Carbon: Its Conservation and Formation; Garcia, C., Nannipieri, P., Hernandez, T., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; Chapter 3; pp. 71–86.

- Lal, R. Soil organic matter and water retention. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 3265–3277.

- Carter, M.R. Soil quality for sustainable land management: Organic matter and aggregation interactions that maintain soil function. Agron. J. 2002, 94, 38–47.

- Raheb, A.; Heidari, A. Effects of Clay Mineralogy and Physicochemical Properties on Potassium Availability under Soil Aquic Conditions. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 12, 747–761.

- Moraru, S.S.; Ene, A.; Badila, A. Physical and Hydro-Physical Characteristics of Soil in the Context of Climate Change. A Case Study in Danube River Basin, SE Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9174.

- Römheld, V.; Kirkby, E.A. Research on potassium in agriculture: Needs and prospects. Plant Soil 2010, 335, 155–180.

- Nieder, R.; Dinesh, K.B.; Scherer, H.W. Fixation and Defixation of Ammonium in Soils: A Review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 1–14.

- Barłóg, P.; Łukowiak, R.; Grzebisz, W. Predicting the content of soil mineral nitrogen based on the content of calcium chloride-extractable nutrients. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2017, 180, 624–635.

- Zheng, Z.; Parent, L.E.; MacLeod, J.A. Influence of soil texture on fertilizer and soil phosphorus transformations in Gleysolic soils. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2003, 83, 395–403.

- Wilson, M.J. Weathering of the primary rock-formingminerals: Processes, products and rates. Clay Miner. 2004, 39, 233–266.

- Erlandsson Lampa, M.; Sverdrup, H.U.; Bishop, K.H.; Belyazid, S.; Ameli, A.; Köhler, S.J. Catchment export of base cations: Improved mineral dissolution kinetics influence the role of water transit time. Soil 2020, 6, 231–244.

- Gavrilescu, M. Water, Soil, and Plants Interactions in a Threatened Environment. Water 2021, 13, 2746.

- Trinh, T.H.; KuShaari, K.; Basit, A. Modeling the Release of Nitrogen from Controlled-Release Fertilizer with Imperfect Coating in Soils and Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 6724–6733.

- Alaoui, I.; El-ghadraoui, O.; Serbouti, S.; Ahmed, H.; Mansouri, I.; El-Kamari, F.; Taroq, A.; Ousaaid, D.; Squalli, W.; Farah, A. The Mechanisms of Absorption and Nutrients Transport in Plants: A Review. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 6, 8–14.

- Comerford, N.B. Soil Factors Affecting Nutrient Bioavailability. In Nutrient Acquisition by Plants; Ecological Studies; Bassiri, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 181, p. 14.

- Oliveira, E.M.M.; Ruiz, H.A.; Alvarez, V.V.H.; Ferreira, P.A.; Costa, F.O.; Almeida, I.C.C. Nutrient supply by mass flow and diffusion to maize plants in response to soil aggregate size and water potential. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2020, 34, 317–327.

- Gransee, A.; Führs, H. Magnesium mobility in soils as a challenge for soil and plant analysis, magnesium fertilization and root uptake under adverse growth conditions. Plant Soil 2013, 368, 5–21.

- Hinsinger, P.; Brauman, A.; Devau, N.; Gérard, F.; Jourdan, C.; Laclau, J.P.; Le Cadre, E.; Jaillard, B.; Plassard, C. Acquisition of phosphorus and other poorly mobile nutrients by roots. Where do plant nutrition models fail? Plant Soil 2011, 348, 29–61.

- Rengel, Z. Availability of Mn, Zn and Fe in the rhizosphere. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2015, 15, 397–409.

- Mauceri, A.; Bassolino, L.; Lupini, A.; Badeck, F.; Rizza, F.; Schiavi, M. Genetic variation in eggplant for nitrogen use efficiency under contrasting NO3− supply. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 393–543.

- Maurel, C.; Nacry, P. Root architecture and hydraulics converge for acclimation to changing water availability. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 744–749.

- Haling, R.E.; Brown, L.K.; Bengough, A.G.; Young, I.M.; Hallett, P.D.; White, P.J.; George, T.S. Root hairs improve root penetration, root-soil contact, and phosphorus acquisition in soils of different strength. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3711–3721.

- Tron, S.; Bodner, G.; Laio, F.; Ridolfi, L.; Leitner, D. Can diversity in root architecture explain plant water use efficiency? A modeling study. Ecol. Model. 2015, 312, 200–210.

- Fang, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, A.; Qiao, S.; Xu, B.; Zhang, S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Chen, Y. Moderate Drought Stress Affected Root Growth and Grain Yield in Old, Modern and Newly Released Cultivars of Winter Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 672.

- Lupini, A.; Preiti, G.; Badagliacca, G.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Sunseri, F.; Monti, M.; Bacchi, M. Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Durum Wheat Under Different Nitrogen and Water Regimes in the Mediterranean Basin. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 607226.

- Becker, M.; Asch, F. Iron toxicity in rice—Conditions and management concepts. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 558–573.

- Vepraskas, M.J. Plant response mechanisms to soil compaction. In Plant-Environment Interactions; Wilkonson, R.E., Ed.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 263–287.

- Bengough, A.G.; McKenzie, B.M.; Hallett, P.D.; Valentine, T.A. Root elongation, water stress, and mechanical impedance: A review of limiting stresses and beneficial root tip traits. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 59–68.

- Correa, J.; Postma, J.A.; Watt, M.; Wojciechowski, T. Soil compaction and the architectural plasticity of root systems. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 6019–6034.

- Clark, L.J.; Whalley, W.R.; Barraclough, P.B. How do roots penetrate strong soil? Plant Soil 2003, 255, 93–104.

- Whalley, W.R.; Bengough, A.G.; Dexter, A.R. Water stress induced by PEG decreases the maximum growth pressure of the roots of pea seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 1689–1694.

- Iijima, M.; Morita, S.; Barlow, P.W. Structure and function of the root cap. Plant Prod. Sci. 2008, 11, 17–27.

- Hunbury, C.D.; Atwell, B.J. Growth dynamics of mechanically impeded lupin roots: Does altered morphology induce hypoxia? Ann. Bot. 2005, 96, 913–924.

- Jin, K.; Shen, J.; Ashton, R.W.; Dodd, I.C.; Parry, M.A.; Whalley, W.R. How do roots elongate in a structured soil? J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4761–4777.

- Bengough, A.G. Root elongation is restricted by axial but not by radial pressures: So what happens in field soil? Plant Soil 2012, 360, 15–18.

- Ramalingam, P.; Kamoshita, A.; Deshmukh, V.; Yaginuma, S.; Uga, Y. Association between root growth angle and root length density of a near-isogenic line of IR64 rice with DEEPER ROOTING 1 under different levels of soil compaction. Plant Prod. Sci. 2017, 20, 162–175.

- Thorup-Kristensen, K.; Cortasa, M.S.; Loges, R. Winter wheat roots grow twice as deep as spring wheat roots, is this important for N uptake and N leaching losses? Plant Soil 2009, 322, 101–114.

- Batey, T. Soil compaction and soil management—A review. Soil Use Manag. 2009, 25, 335–345.

- Jobbágy, E.G.; Jackson, R.B. The distribution of soil nutrients with depth: Global patterns and the imprint of plants. Biogeochemistry 2001, 53, 51–77.

- Valentine, T.A.; Hallett, P.D.; Binnie, K.; Young, M.W.; Squire, G.R.; Hawes, C.; Bengough, A.G. Soil strength and macropore volume limit root elongation rates in many UK agricultural soils. Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 259–270.

- Sitaula, B.K.; Hansen, S.; Sitaula, J.I.B.; Bakken, L.R. Effects of soil compaction on N2O emission in agricultural soil. Chemosphere-Glob. Chang. Sci. 2000, 2, 367–371.

- Chamindu Deepagoda, T.K.K.; Clough, T.J.; Thomas, S.M.; Balaine, N.; Elberling, B. Density Effects on Soil-Water Characteristics, Soil-Gas Diffusivity, and Emissions of N2O and N2 from a Re-packed Pasture Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 83, 118–125.

- Ruser, R.; Flessa, H.; Russow, R.; Schmidt, G.; Buegger, F.; Munch, J.C. Emission of N2O, N2 and CO2 from soil fertilized with nitrate: Effect of compaction, soil moisture and rewetting. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 263–274.

- Soane, B.; Van Ouwerkerk, C. Implications of soil compaction in crop production for the quality of the environment. Soil Till Res. 1995, 35, 5–22.

- Sommer, S.G.; Hutchings, N.J. Ammonia emission from field applied manure and its reduction. Eur. J. Agron. 2001, 15, 1–15.

- Onwuka, B.; Mang, B. Effects of soil temperature on some soil properties and plant growth. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 2018, 8, 34–37.

- Fang, C.M.; Smith, P.; Moncrieff, J.B.; Smith, J.U. Similar response of labile and resistant soil organic matter pools to changes in temperature. Nature 2005, 436, 881–883.

- Elbasiouny, H.; El-Ramady, H.; Elbehiry, F.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S. Plant Nutrition under Climate Change and Soil Carbon Sequestration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 914.

- Gahoonia, T.S.; Nielsen, N.E. Phosphorus uptake and growth of root hairless barley mutant (bald root barley) and wild type in low and high–p soils. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 1759–1766.

- Yilvainio, K.; Pettovuori, T. Phosphorus acquisition by barley (Hordeum yulgar) at suboptimal soil temperature. Agric. Food Sci. 2012, 21, 453–461.

- Lahti, M.; Aphalo, P.; Finér, L.; Ryyppö, A.; Lehto, T.; Mannerkoski, H. Effects of soil temperature on shoot and root growth and nutrient uptake of 5-year-old Norway spruce seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 115–122.

- Gavelienė, V.; Jurkonienė, S.; Jankovska-Bortkevič, E.; Švegždienė, D. Effects of Elevated Temperature on Root System Development of Two Lupine Species. Plants 2022, 11, 192.

- Huang, B.R.; Taylor, H.M.; McMichael, B.L. Effects of Temperature on the Development of Metaxylem in Primary Wheat Roots and Its Hydraulic Consequence. Ann. Bot. 1991, 67, 163–166.

- Falah, M.A.F.; Wajima, T.; Yasutake, D.; Sago, Y.; Kitano, M. Responses of root uptake to high temperature of tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) in soil-less culture. J. Agric. Technol. 2010, 6, 543–558.

- Xia, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Fu, Y.; Lu, H. Effects of Root Zone Warming on Maize Seedling Growth and Photosynthetic Characteristics Under Different Phosphorus Levels. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 746152.

- Fageria, N.K.; Barbosa Filho, M.B. Influence of pH on Productivity, Nutrient Use Efficiency by Dry Bean, and Soil Phosphorus Availability in a No-Tillage System. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 39, 1016–1025.

- Jackson, K.; Meetei, T.T. Influence of soil pH on nutrient availability: A Review. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2018, 5, 708–713.

- Neina, D. The Role of Soil pH in Plant Nutrition and Soil Remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 2019, 5794869.

- Bojórquez-Quintal, E.; Escalante-Magaña, C.; Echevarría-Machado, I.; Martínez-Estévez, M. Aluminum, a friend or foe of higher plants in acid soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1767.

- Błaszyk, R. Effects of Lime Fertilizer Reactivity on Selected Chemical Properties of Soil and Crop Yielding in Two Different Tillage Systems. Doctoral Thesis, Department of Agricultural Chemistry and Environmental Biogeochemistry, Poznan University of Life Sciences, Poznań, Poland, 2020; p. 237. (In Polish).

- McCauley, A.; Jones, C.; Jacobsen, J. Soil pH and Organic Matter. Montana State University (MSU) Extension. Available online: https://apps.msuextension.org/publications/pub.html?sku=4449-8 (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Rangel, A.F.; Madhusudana, R.I.; Johannes, H.W. Intracellular distribution and binding state of aluminum in root apices of two common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) genotypes in relation to Al toxicity. Physiol. Plant. 2009, 135, 162–173.

- Rahman, M.A.; Lee, S.H.; Ji, H.C.; Kabir, A.H.; Jones, C.S.; Lee, K.W. Importance of Mineral Nutrition for Mitigating Aluminum Toxicity in Plants on Acidic Soils: Current Status and Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3073.

- Bose, J.; Babourina, O.; Rengel, Z. Role of magnesium in alleviation of aluminum toxicity in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2251–2264.

- Čiamporová, M. Morphological and Structural Responses of Plant Roots to Aluminium at Organ, Tissue, and Cellular Levels. Biol. Plant. 2002, 45, 161–171.

- Singh, S.; Tripathi, D.K.; Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.K.; Chauhan, D.K.; Vaculík, M. Toxicity of aluminium on various levels of plant cells and organism: A review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 177–193.

- Zhao, X.Q.; Shen, R.F. Aluminum–Nitrogen Interactions in the Soil–Plant System. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 807.

- Ma, D.; Wang, J.; Xue, J.; Yue, Z.; Xia, S.; Song, L.; Gao, H. Effects of Soil pH on Gaseous Nitrogen Loss Pathway via Feammox Process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10393.

- Faria, J.M.S.; Teixeira, D.M.; Pinto, A.P.; Brito, I.; Barrulas, P.; Carvalho, M. Aluminium, Iron and Silicon Subcellular Redistribution in Wheat Induced by Manganese Toxicity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8745.

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712831.

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131.

- Mohanavelu, A.; Naganna, S.R.; Al-Ansari, N. Irrigation Induced Salinity and Sodicity Hazards on Soil and Groundwater: An Overview of Its Causes, Impacts and Mitigation Strategies. Agriculture 2021, 11, 983.

- Munns, R.; Passioura, J.B.; Colmer, T.D.; Byrt, C.S. Osmotic Adjustment and Energy Limitations to Plant Growth in saline Soil. New Phytol. 2019, 225, 1091–1096.

- Shahriaripour, R.; Tajabadi Pour, A.; Mozaffari, V. Effects of Salinity and Soil Phosphorus Application on Growth and Chemical Compositiono Pistachio Seedlings. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 144–158.

- Rengasamy, P. Soil processes affecting crop production in salt-affected soils. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 613–620.

- Maathuis, F.J.M. Sodium in plants: Perception, signalling, and regulation of sodium fluxes. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 849–858.

- Kronzucker, H.J.; Coskun, D.; Schulze, L.M.; Wong, J.R.; Britto, D.T. Sodium as nutrient and toxicant. Plant Soil 2013, 369, 1–23.

- Raddatz, N.; Morales de los Ríos, L.; Lindahl, M.; Quintero, F.J.; Pardo, J.M. Coordinated Transport of Nitrate, Potassium, and Sodium. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 247.

- Rosales, M.A.; Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Peinado-Torrubia, P.; Díaz-Rueda, P.; Álvarez, R.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M. Chloride Improves Nitrate Utilization and NUE in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 442.

- Acikbas, S.; Ozyazici, M.A.; Bektas, H. The Effect of Salinity on Root Architecture in Forage Pea (Pisum sativum ssp. arvense L.). Legume Res. 2021, 44, 407–412.

- Lal, R. Soil health and carbon management. Food Energy Secur. 2016, 5, 212–222.

- Kopittke, P.M.; Dalal, R.C.; Finn, D.; Menzies, N.W. Global changes in soil stocks of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur as influenced by long-term agricultural production. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 2509–2519.

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9575–9580.

- Huang, S.; Yang, W.; Ding, W.; Jia, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; He, P.; Yang, J. Estimation of Nitrogen Supply for Summer Maize Production through a Long-Term Field Trial in China. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1358.

- Luis, L.; Gilles, B.; Bruna, G.; Juliette, A.; Josette, G. 50 year trends in nitrogen use efficiency of world cropping systems: The relationship between yield and nitrogen input to cropland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 105011.

- Wei, X.; Shao, M.; Gale, W.; Li, L. Global pattern of soil carbon losses due to the conversion of forests to agricultural land. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4062.

- Xue, Z.; An, S. Changes in Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen at a Small Watershed Scale as the Result of Land Use Conversion on the Loess Plateau. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4757.

- Livsey, J.; Alavaisha, E.; Tumbo, M.; Lyon, S.W.; Canale, A.; Cecotti, M.; Lindborg, R.; Manzoni, S. Soil Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Contents along a Gradient of Agricultural Intensity in the Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. Land 2020, 9, 121.

- Haddaway, N.R.; Hedlund, K.; Jackson, L.E.; Kätterer, T.; Lugato, E.; Thomsen, I.K.; Jørgensen, H.B.; Isberg, P.E. How does tillage intensity afect soil organic carbon? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 2017, 6, 30.

- Krauss, M.; Wiesmeier, M.; Don, A.; Cuperus, F.; Gattinger, A.; Gruberf, S.; Haagsma, W.K.; Peign’e, J.; Chiodelli Palazzoli, M.; Schulz, F.; et al. Reduced tillage in organic farming affects soil organic carbon stocks in temperate Europe. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 2016, 105262.

- Powlson, D.S.; Bhogal, A.; Chambers, B.J.; Coleman, K.; Macdonald, A.J.; Goulding, W.T.; Whitmore, A.P. The potential to increase soil carbon stocks through reduced tillage or organic material additions in England and Wales: A case study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 146, 23–33.

- Szajdak, L.; Życzyńska-Bałoniak, I.; Meysner, T.; Blecharczyk, A. Bound amino acids in humic acids from arable cropping systems. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2004, 167, 562–567.

- Khalil, M.I.; Rahman, M.S.; Schmidhalter, U.; Olfs, H.-W. Nitrogen fertilizer–induced mineralization of soil organic C and N in six contrasting soils of Bangladesh. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2007, 170, 210–218.

- Barre, P.; Montagnier, C.; Chenu, C.; Abbadie, L.; Velde, B. Clay minerals as a soil potassium reservoir: Observation and quantification through X-ray diffraction. Plant Soil 2008, 302, 213–220.

- Khan, H.R.; Elahi, S.F.; Hussain, M.S.; Adachi, T. Soil Characteristics and Behavior of Potassium under Various Moisture Regimes. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1994, 40, 243–254.

- Ray, D.K.; Ramankutty, N.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1293.

- Schauberger, B.; Ben-Ari, T.; Makowski, D.; Kato, T.; Kato, H.; Ciais, P. Yield trends, variability and stagnation analysis of major crops in France over more than a century. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16865.

- Bindraban, P.S.; Dimkpa, C.; Nagarajan, L.; Roy, A.; Rabbinge, R. Revisiting fertilisers and fertilization strategies for improved nutrient uptake by plants. Boil. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 897–911.

- Spiertz, J.H.J. Nitrogen, sustainable agriculture and food security. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 43–55.

- Grzebisz, W.; Niewiadomska, A.; Przygocka-Cyna, K. Nitrogen Hotspots on the farm—A practice-oriented approach. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1305.

- Berbell, J.; Martinez-Dalmau, J. A simple agro-economic model for optimal farm nitrogen application under yield uncertainty. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1107.

- Olfs, H.-W.; Blankenau, K.; Brentrup, F.; Jasper, J.; Link, A.; Lammel, J. Soil- and plant-based nitrogen-fertilizer recommendations in arable farming. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 414–431.

- Córdova, C.; Barrera, J.A.; Magna, C. Spatial variation in nitrogen mineralization as a guide for variable application of nitrogen fertilizer to cereal crops. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 110, 83–88.

- Herath, A.; Ma, B.L.; Shang, J.; Liu, J.; Dong, T.; Jiao, X.; Kovacs, J.M.; Walters, D. On-farm spatial characterization of soil mineral nitrogen, crop growth, and yield of canola as affected by different rates of nitrogen application. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 98, 1–14.

- Stamatiadis, S.; Schepers, J.S.; Evangelou, E.; Tsadilas, C.; Glampedakis, M.; Dercas, N.; Spyropoulos, N.; Dalezios, N.R.; Eskridge, K. Variable-rate nitrogen fertilization of winter wheat under high spatial resolution. Precis. Agric. 2018, 19, 570–587.

- Klepper, B.; Rickman, R.W.; Waldman, S.; Chevalier, P. The physiological life cycle of wheat: Its use in breeding and crop management. Euphytica 1998, 100, 341–347.

- Vizzari, M.; Santaga, F.; Benincasa, P. Sentinel 2-based nitrogen VRT fertilization in wheat: Comparison between traditional and simple precision practices. Agronomy 2019, 9, 278.