Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

COVID-19 can spread throughout the central nervous system, impacting the brain and spinal cord, and neurological symptoms could explain this in people infected with long-term infection

- COVID-19

- brain

- neurological manifestations

1. Neurological Effects of COVID-19

Coronavirus was initially observed as a pathogen responsible for respiratory illness with cough, shortness of breath, fever, muscle pain, headache, sore throat with loss of taste and smell. These symptoms were declared by the center for disease control (CDC). Still, this virus was later considered a pathogen that negatively impacted multiple organs. Its heterogeneity showed more neurological disorders, indicating its RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of its infected patients in acute and long-term phases [1]. SARS-CoV-2 may directly impact the white and grey matter of the brain and spine with demyelinating lesions and symptoms of seizures, ataxia, dizziness, and cerebrovascular illness. French and Turkish scientists also reported neurological symptoms during coronavirus infection in patients with agitation, delirium, ischemic stroke, and encephalopathy, along with anosmia and dysgeusia, while headache is the most common manifestation [2]. This viral infection of the respiratory tract has the strength to cause psychiatric and neurological problems because COVID-19 is neurotropic in nature and has the strength to enter into the central nervous system, while antibodies of COVID-19 have been observed in deceased patient’s cerebrospinal fluid. It is essential to consider COVID-19 as a neuropsychiatric manifestation of long-term complications [3].

Another study observed that obscured monocular vision, dysphoria, vomiting, deliria, coma, brain herniation, loss of consciousness, up-rolling eyeballs, vomiting, four-limb twitching, confusion, and seizures are common in patients infected with the novel coronavirus [1]. However, the neurotropic and neuro-invasive symptoms were observed since the first case of coronavirus in human in 2003 [4]. A few neurological manifestations due to novel coronavirus are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1. List of neurological disorders caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Disorder | Mean Age (Years) | Onset of Disease | Percentage of Infected Patients | Effect | Treatment/Drug | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dizziness | 39 | Shortly after COVID-19 | 16.8% | Inflammation of the inner ear nerve that connected to the brain | Betahistine, danshenchuandomazine, meclizine, benzodiazepine, steroids, vestibular rehabilitation | [1][5][6][7] |

| Ischemic stroke and hemorrhage | 67.4 | In the first week of respiratory symptoms with moderate pulmonary involvement | 83.7% stroke and 20.8% hemorrhage | Numbness or weakness in the face, arm, or leg on one side of the body, confusion, difficulty speaking, dizziness, loss of balance, and severe headache | Apixaban 5 mg twice daily, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg every 12 h | [8][9][10][11] |

| Encephalopathy | 66 | At the time of documented COVID-19 infection | 8.7% while 31.8% in the case study of 509 COVID-19 hospitalized patients | Confusion, non-oriented to time, person, or place, seizures, and sleepiness | High-dose IV steroids, IV immunoglobulin, and immunomodulators (e.g., rituximab) | [12][13][14] |

| Delirium | 77.7 | As a sixth primary symptom of coronavirus | 28% | Confusion, disorientation, inattention, and cognitive disturbances commonly affect older persons | Haloperidol, melatonin as prophylaxis | [15][16] |

| Anosmia and Dysguesia | 47 | Initial symptoms for coronavirus infected patients | 47% 54/114 patients and 5.1% anosmia while 5.6% dysgeusia in another study of 214 infected patients | Official symptoms for COVID-19 | Caffeine in coffee | [17][18][19][20] |

| Dysautonomia (also known as secondary COVID-19 infection) | 48 | Onset 6 weeks following initial COVID-19 symptoms, within the last week of the illness, also seen symptom onset occur within three months of recovery. | 50% | Postural lightheadedness and near-syncope, fatigue, activity intolerance, hypertensive response, and orthostatic hypotension | Cefazolin and acebutolol (in case of significant hypertension) | [21][22][23][24] |

| Microbleed | 67.7 | Fever, productive cough, myalgias, headache during coronavirus attack | 24.4% | Confusion, agitation, and delayed recovery of consciousness | Co-amoxicillin, hydroxychloroquine, piperacillin, tazobactam, azithromycin, lopinavir, ritonavir, levofloxacin, tazobactam | [25][26] |

| Coma | 66 | Severe illness due to viral attack | 15% | Breathlessness, an erratic heart rate and fatigue, altered mental status, and inability to wakeup off leads to unconsciousness | Modafinil and carbidopa/levodopa, amantadine, aspirin, statin | [27] |

| Brain herniation, cerebral edema | 57 | Positive for SARS-CoV 2, fatigue, and fever | 3.9% | Hypertension, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and multiple juxtacortical hemorrhages (CT scan observation) | Midazolam, low dose norepinephrine | [27] |

| Cerebral ataxia and myoclonus | 59.6 | Acute onset within one month of COVID-19 | 40% ataxia and 46.7% Myoclonus | Spontaneous, action-induced, posture-induced, and mild dysarthria | Methylprednisolone daily for 5 days, clonazepam after 10 days of symptoms, levetiracetam started on day 14 | [28] |

| Seizures | 76- and 82-years old patient’s case history | Patients suffering from coronavirus | 23% detected by anti-CoV IgM | Convulsive activity and subtle twitching | Antiseizure medication (ASM) therapy, brivaracetam, lacosamide, carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, benzodiazepines, valproic acid, vancomycin, meropenem, and Acyclovir for CSF coverage, all drugs should be prescribed cautiously by following doctor’s advice in which patient’s health history is essential | [4][29] |

2. Routes for Entry of COVID-19 into the Brain and Neurological Manifestations

COVID-19 can spread throughout the central nervous system, impacting the brain and spinal cord, and neurological symptoms could explain this in people infected with long-term infection [30]. This novel virus enters into the brain and tissues through multiple ways, but there is a semi-permeable membrane, a blood–brain barrier that allows only selective nutrients, pathogens, and toxins to flow to and from the brain. This barrier strictly controls the neuronal microenvironment while maintaining neurons’ normal function. However, in the case of other diseases, this blood–brain barrier breaks down, and this dysfunction leads to the cause of infection, that is neurological deficits [31].

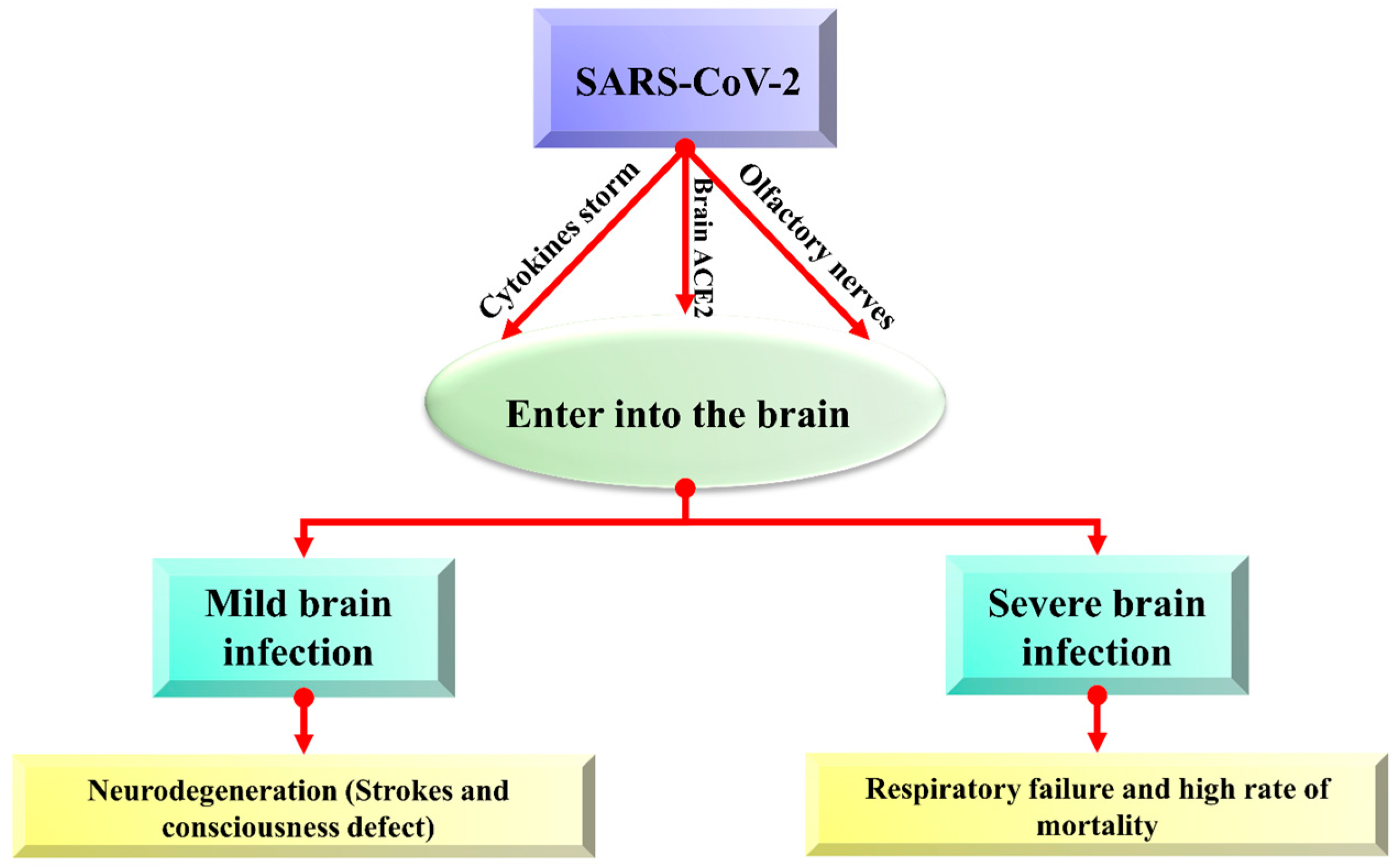

Brain cells can be harmed due to the triggered production of immune molecules and reduced blood flow to the brain. Sometimes, this contagious and deadly coronavirus directly enters the brain and affects its functionality. Viruses may spread to the brain via the lining of the nasal cavity in olfactory mucosa that borders the brain and infects astrocytes over other cells, and neurological symptoms can be described in the brain [32]. About 0.04% of long-term severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) infected patients showed symptoms of the affected central nervous system, and this problem is becoming scarier, while only 0.2% of neurological symptoms were observed with MERS [33]. There are possibly three main ways (olfactory bulb, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) pathway, and cytokine storm) that coronavirus follows to enter the brain, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The overview of possible entry routes of SARS-CoV-2 in the brain.

2.1. Coronavirus Enters the Brain via ACE2 Pathway

The COVID-19 virus enters the brain via angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 receptors present in the CNS and is particularly expressed in the nasal mucosa [34]. A transmembrane protein ACE-2 (Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2) is typically recognized for its carboxypeptidase activity and its physiological role in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) [35]. ACE-2 (Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2) has an ability to express in many tissues of the brain, and novel coronavirus can directly interact with this enzyme in the capillary endothelium due to which the blood–brain barrier is devastated, which enhances virus entry into the brain and affect the central nervous system, because ACE-2 can express throughout the brain. Viral mRNA also interacts with ACE-2 in COVID-19 infected patients. Increased neurological infections are due to a novel coronavirus that is promoted to enter the central nervous system because of the abundance of ACE-2 enzymes in the brain [36][37]. Viral spike protein interacts with the ACE-2 receptor, an important regulator of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). Its expression has also been studied in the retina, cerebellum, cerebrum, and olfactory mucosa [38]. The virus enters the brain via other receptor cells, too, like neuropilin-1 (NRP1), basigin (BSG; CD147), cathepsin L (CTSL), and serine protease 2 and 4 (TMPRSS2/4) [38][39][40].

2.2. Coronavirus Entry into the Brain via Olfactory Pathway

The presence of a high amount of virus in the nasal epithelium suggests that novel coronavirus can travel to the brain through olfactory nerves. Such viruses that can invade neurons can bind with olfactory receptor neurons [41]. nCoV-19 migrates from the cribriform plate by following the trigeminal pathway and penetrating the olfactory mucosa, which causes smell loss and may enter the brain [42]. The virus attaches to olfactory receptors, enters the neuroepithelium, then spreads in the brain stem, thalamus, and medulla oblongata and causes serious disorders. Postmortem reports also provided evidence of its presence in neural endothelial cells in frontal lobe tissues [43].

2.3. Coronavirus Entry in the Brain via Cytokine Storm

Cerebrospinal fluid and the blood–brain barrier help in creating a balanced environment to protect the brain from viruses and other pathogens, but these can enter via peripheral nerves and olfactory sensory neurons. SARS-CoV-2 trigger pro-inflammatory microglia phenotype (M1 phenotype) that activate proinflammatory cytokines and enhance neurodegenerative disorders [44]. Activating proinflammatory cytokines enhances neutrophil activation, resulting in the characteristic cytokine storm. Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-12, interferon (IFN) γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, which mainly targets the lung tissue, are also released along with proinflammatory cytokines. Damaged neuroepithelium cells cause inflammation and activate cytokine storms that damage neurons and neurological disorders. Cytokine storm is also associated with immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) and other encephalopathies associated with cytokine storm [45].

Increased levels of cytokines, including Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (M-CSF), interferon γ-induced protein (IP-10), and Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1-α (MIP1-α). The activated cytokine storm results in a hyperactive immune response that leads to inflammation and inflammatory cytokines, followed by a delayed production of interferons (IFN). The released cytokines stimulate the neutrophils that triggers inflammation when the virus replicates within the macrophages resulting in apoptosis [46].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12070971

References

- Cheng, Q.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J. Infectivity of human coronavirus in the brain. EBioMedicine 2020, 56, 102799.

- Bougakov, D.; Podell, K.; Goldberg, E. Multiple neuroinvasive pathways in COVID-19. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 564–575.

- Butler, M.; Pollak, T.A.; Rooney, A.G.; Michael, B.D.; Nicholson, T.R. Neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19. Br. Med. J. Publ. 2020, 371, m3871.

- Asadi-Pooya, A.A. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure 2020, 79, 49–52.

- Arabi, Y.; Harthi, A.; Hussein, J.; Bouchama, A.; Johani, S.; Hajeer, A.; Saeed, B.; Wahbi, A.; Saedy, A.; AlDabbagh, T. Severe neurologic syndrome associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS-CoV). Infection 2015, 43, 495–501.

- Saniasiaya, J.; Kulasegarah, J. Dizziness and COVID-19. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100, 29–30.

- Kong, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jian, J. 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia with onset of dizziness: A case report. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 506.

- Katz, J.M.; Libman, R.B.; Wang, J.J.; Sanelli, P.; Filippi, C.G.; Gribko, M.; Pacia, S.V.; Kuzniecky, R.I.; Najjar, S.; Azhar, S. Cerebrovascular complications of COVID-19. Stroke 2020, 51, e227–e231.

- Qureshi, A.I.; Baskett, W.I.; Huang, W.; Shyu, D.; Myers, D.; Raju, M.; Lobanova, I.; Suri, M.F.K.; Naqvi, S.H.; French, B.R. Acute ischemic stroke and COVID-19: An analysis of 27 676 patients. Stroke 2021, 52, 905–912.

- Karvigh, S.A.; Vahabizad, F.; Banihashemi, G.; Sahraian, M.A.; Gheini, M.R.; Eslami, M.; Marhamati, H.; Mirhadi, M.S. Ischemic stroke in patients with COVID-19 disease: A report of 10 cases from Iran. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 50, 239–244.

- Zakeri, A.; Jadhav, A.P.; Sullenger, B.A.; Nimjee, S.M. Ischemic stroke in COVID-19-positive patients: An overview of SARS-CoV-2 and thrombotic mechanisms for the neurointerventionalist. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2021, 13, 202–206.

- Haider, A.; Siddiqa, A.; Ali, N.; Dhallu, M. COVID-19 and the brain: Acute encephalitis as a clinical manifestation. Cureus 2020, 12, e10784.

- Umapathi, T.; Quek, W.M.J.; Yen, J.M.; Khin, H.S.W.; Mah, Y.Y.; Chan, C.Y.J.; Ling, L.M.; Yu, W.-Y. Encephalopathy in COVID-19 patients; viral, parainfectious, or both? Eneurologicalsci 2020, 21, 100275.

- Elkind, M.S.; Cucchiara, B.L.; Koralnik, I.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Kasner, S.E. COVID-19: Neurologic Complications and Management of Neurologic Conditions. 2021. Available online: https://www.medilib.ir/uptodate/show/128153 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Kennedy, M.; Helfand, B.K.I.; Gou, R.Y.; Gartaganis, S.L.; Webb, M.; Moccia, J.M.; Bruursema, S.N.; Dokic, B.; McCulloch, B.; Ring, H.; et al. Delirium in Older Patients With COVID-19 Presenting to the Emergency Department. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2029540.

- Velásquez-Tirado, J.D.; Trzepacz, P.T.; Franco, J.G. Etiologies of Delirium in Consecutive COVID-19 Inpatients and the Relationship Between Severity of Delirium and COVID-19 in a Prospective Study With Follow-Up. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 33, 210–218.

- Klopfenstein, T.; Kadiane-Oussou, N.J.; Toko, L.; Royer, P.Y.; Lepiller, Q.; Gendrin, V.; Zayet, S. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Médecine Mal. Infect. 2020, 50, 436–439.

- Vaira, L.A.; Deiana, G.; Fois, A.G.; Pirina, P.; Madeddu, G.; De Vito, A.; Babudieri, S.; Petrocelli, M.; Serra, A.; Bussu, F. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: Single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck 2020, 42, 1252–1258.

- Zahra, S.A.; Iddawela, S.; Pillai, K.; Choudhury, R.Y.; Harky, A. Can symptoms of anosmia and dysgeusia be diagnostic for COVID-19? Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01839.

- Hosseini, A.; Mirmahdi, E.; Moghaddam, M.A. A new strategy for treatment of Anosmia and Ageusia in COVID-19 patients. Integr. Respir. Med. 2020, 1, 2.

- Goodman, B.P.; Khoury, J.A.; Blair, J.E.; Grill, M.F. COVID-19 Dysautonomia. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 624968.

- Eshak, N.; Abdelnabi, M.; Ball, S.; Elgwairi, E.; Creed, K.; Test, V.; Nugent, K. Dysautonomia: An Overlooked Neurological Manifestation in a Critically ill COVID-19 Patient. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 360, 427–429.

- Barizien, N.; Le Guen, M.; Russel, S.; Touche, P.; Huang, F.; Vallée, A. Clinical characterization of dysautonomia in long COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14042.

- Alyesh, D.; Mathew, J.; Jordan, R.; Choe, W.; Sundaram, S. COVID-19 Dysautonomia: An Important Component of “Long-Hauler Syndrome”. EP Lab Dig. 2021, 21, 36–37.

- Fitsiori, A.; Pugin, D.; Thieffry, C.; Lalive, P.; Vargas, M.I. Unusual microbleeds in brain MRI of COVID-19 patients. J. Neuroimaging 2020, 30, 593–597.

- Jegatheeswaran, V.; Chan, M.W.; Chakrabarti, S.; Fawcett, A.; Chen, Y.A. Neuroimaging Findings of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Canadian Retrospective Observational Study. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2022, 73, 179–186.

- Roy, D.; Song, J.; Awad, N.; Zamudio, P. Treatment of unexplained coma and hypokinetic-rigid syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e239781.

- Chan, J.L.; Murphy, K.A.; Sarna, J.R. Myoclonus and cerebellar ataxia associated with COVID-19: A case report and systematic review. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 3517–3548.

- Hepburn, M.; Mullaguri, N.; George, P.; Hantus, S.; Punia, V.; Bhimraj, A.; Newey, C.R. Acute symptomatic seizures in critically ill patients with COVID-19: Is there an association? Neurocritical Care 2021, 34, 139–143.

- Alquisiras-Burgos, I.; Peralta-Arrieta, I.; Alonso-Palomares, L.A.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.E.; Salmerón-Bárcenas, E.G.; Aguilera, P. Neurological Complications Associated with the Blood-Brain Barrier Damage Induced by the Inflammatory Response During SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 520–535.

- Chen, Z.; Li, G. Immune response and blood–brain barrier dysfunction during viral neuroinvasion. Innate Immun. 2021, 27, 109–117.

- Marshall, M. COVID and the brain: Researchers zero in on how damage occurs. Nature 2021, 595, 484–485.

- Marshall, M. How COVID-19 can damage the brain. Nature 2020, 585, 342–343.

- Li, L.; Hill, J.; Spratt, J.C.; Jin, Z. Myocardial injury in severe COVID-19: Identification and management. Resuscitation 2021, 160, 16–17.

- El-Aziz, A.; Mohamed, T.; Al-Sabi, A.; Stockand, J.D. Human recombinant soluble ACE2 (hrsACE2) shows promise for treating severe COVID 19. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 258.

- Mao, X.-Y.; Jin, W.-L. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Consideration for Brain Infection. Neuroscience 2020, 437, 130–131.

- Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Ray, B.; Tuladhar, S.; Bhat, A.; Paneyala, S.; Patteswari, D.; Sakharkar, M.K.; Hamdan, H.; Ojcius, D.M.; Bolla, S.R.; et al. Does COVID-19 contribute to development of neurological disease? Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2021, 9, 48–58.

- Naik, G.O.A. COVID-19 and the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 1105–1107.

- Lou, J.J.; Movassaghi, M.; Gordy, D.; Olson, M.G.; Zhang, T.; Khurana, M.S.; Chen, Z.; Perez-Rosendahl, M.; Thammachantha, S.; Singer, E.J.; et al. Neuropathology of COVID-19 (neuro-COVID): Clinicopathological update. Free. Neuropathol. 2021, 2, 2.

- DeKosky, S.T.; Kochanek, P.M.; Valadka, A.B.; Clark, R.S.B.; Chou, S.H.; Au, A.K.; Horvat, C.; Jha, R.M.; Mannix, R.; Wisniewski, S.R.; et al. Blood Biomarkers for Detection of Brain Injury in COVID-19 Patients. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1–43.

- Butowt, R.; Meunier, N.; Bryche, B.; von Bartheld, C.S. The olfactory nerve is not a likely route to brain infection in COVID-19: A critical review of data from humans and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 809–822.

- Boldrini, M.; Canoll, P.D.; Klein, R.S. How COVID-19 Affects the Brain. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 682–683.

- Desai, I.; Manchanda, R.; Kumar, N.; Tiwari, A.; Kumar, M. Neurological manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019: Exploring past to understand present. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 773–785.

- Mehta, O.P.; Bhandari, P.; Raut, A.; Kacimi, S.E.O.; Huy, N.T. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Comprehensive Review of Clinical Presentation. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 582932.

- Pensato, U.; Muccioli, L.; Cani, I.; Janigro, D.; Zinzani, P.L.; Guarino, M.; Cortelli, P.; Bisulli, F. Brain dysfunction in COVID-19 and CAR-T therapy: Cytokine storm-associated encephalopathy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 968–979.

- Hirawat, R.; Saifi, M.A.; Godugu, C. Targeting inflammatory cytokine storm to fight against COVID-19 associated severe complications. Life Sci. 2021, 267, 118923.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!