Immunotherapy aims to engage various immune cells in the elimination of cancer cells. Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in the circulation and have unique mechanisms by which they can kill cancer cells opsonized by antibodies. However, neutrophil effector functions are limited by the inhibitory receptor SIRPα, when it interacts with CD47. The CD47 protein is expressed on all cells in the body and acts as a ‘don’t eat me’ signal to prevent tissue damage. Cancer cells can express high levels of CD47 to circumvent tumor elimination. Thus, blocking the interaction between CD47 and SIRPα may enhance anti-tumor effects by neutrophils in the presence of tumor-targeting monoclonal antibodies. Blocking the CD47-SIRPα interaction may therefore potentiate neutrophil-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) towards cancer cells, and various inhibitors of the CD47-SIRPα axis are now in clinical studies.

- tumor

- antibody therapy

- neutrophil

- CD47-SIRPα

- immune checkpoint

1. CD47-SIRPα as an Innate Immune Checkpoint in Neutrophil-Mediated Tumor Killing

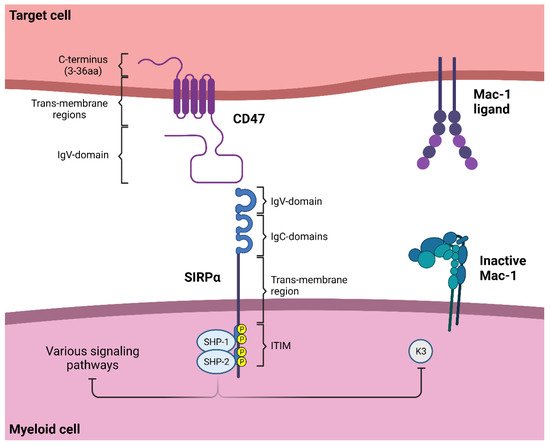

1.1. SIRPα Signaling

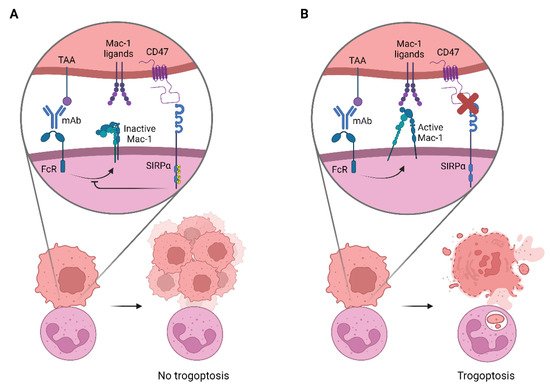

1.2. Neutrophil Effector Functions Influenced by CD47-SIRPα

1.3. The Innate Immune Checkpoint CD47-SIRPα in Cancer

2. Targeting CD47-SIRPα to Potentiate Antibody Therapy

2.1. CD47-Targeting Agents

2.2. Anti-SIRPα mAbs

2.3. Alternative Ways to Disrupt CD47-SIRPα Interactions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14143366

References

- Ellen M. van Beek; Fiona Cochrane; A. Neil Barclay; Timo K. Van Den Berg; Signal Regulatory Proteins in the Immune System. The Journal of Immunology 2005, 175, 7781-7787, 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7781.

- S Adams; L J Van Der Laan; E Vernon-Wilson; C Renardel De Lavalette; E A Döpp; C D Dijkstra; D L Simmons; T K Van Den Berg; Signal-regulatory protein is selectively expressed by myeloid and neuronal cells.. The Journal of Immunology 1998, 161, 1853-59, .

- T Vandenberg; Jeffrey Yoder; G Litman; On the origins of adaptive immunity: innate immune receptors join the tale. Trends in Immunology 2004, 25, 11-16, 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.006.

- Deborah Hatherley; Karl Harlos; D. Cameron Dunlop; David I. Stuart; A. Neil Barclay; The Structure of the Macrophage Signal Regulatory Protein α (SIRPα) Inhibitory Receptor Reveals a Binding Face Reminiscent of That Used by T Cell Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 14567-14575, 10.1074/jbc.m611511200.

- M.I. Reinhold; F.P. Lindberg; D. Plas; S. Reynolds; M.G. Peters; E.J. Brown; In vivo expression of alternatively spliced forms of integrin-associated protein (CD47). Journal of Cell Science 1995, 108, 3419-3425, 10.1242/jcs.108.11.3419.

- Eric J. Brown; Integrin-associated protein (CD47) and its ligands. Trends in Cell Biology 2001, 11, 130-135, 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01906-1.

- E Brown; L Hooper; T Ho; H Gresham; Integrin-associated protein: a 50-kD plasma membrane antigen physically and functionally associated with integrins.. Journal of Cell Biology 1990, 111, 2785-2794, 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2785.

- I G Campbell; P S Freemont; W Foulkes; J Trowsdale; An ovarian tumor marker with homology to vaccinia virus contains an IgV-like region and multiple transmembrane domains.. Cancer Research 1992, 52, 5416-5420, .

- Per-Arne Oldenborg; CD47: A Cell Surface Glycoprotein Which Regulates Multiple Functions of Hematopoietic Cells in Health and Disease. ISRN Hematology 2013, 2013, 1-19, 10.1155/2013/614619.

- Peihua Jiang; Carl F. Lagenaur; Vinodh Narayanan; Integrin-associated Protein Is a Ligand for the P84 Neural Adhesion Molecule. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 559-562, 10.1074/jbc.274.2.559.

- Martina Seiffert; Charles Cant; Zhengjun Chen; Irene Rappold; Wolfram Brugger; Lothar Kanz; Eric J. Brown; Axel Ullrich; Hans-Jörg Bühring; Human Signal-Regulatory Protein Is Expressed on Normal, But Not on Subsets of Leukemic Myeloid Cells and Mediates Cellular Adhesion Involving Its Counterreceptor CD47. Blood 1999, 94, 3633-3643, 10.1182/blood.v94.11.3633.

- Elizabeth F. Vernon-Wilson; Wai-Jing Kee; Antony C. Willis; A. Neil Barclay; David L. Simmons; Marion H. Brown; CD47 is a ligand for rat macrophage membrane signal regulatory protein SIRP (OX41) and human SIRPα 1. European Journal of Immunology 2000, 30, 2130-2137, 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8%3C2130::AID-IMMU2130%3E3.0.CO;2-8.

- Deborah Hatherley; Stephen Graham; Jessie Turner; Karl Harlos; David I. Stuart; A. Neil Barclay; Paired Receptor Specificity Explained by Structures of Signal Regulatory Proteins Alone and Complexed with CD47. Molecular Cell 2008, 31, 266-277, 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.026.

- Meike E. W. Logtenberg; J. H. Marco Jansen; Matthijs Raaben; Mireille Toebes; Katka Franke; Arianne M. Brandsma; Hanke L. Matlung; Astrid Fauster; Raquel Gomez-Eerland; Noor A. M. Bakker; et al. Glutaminyl cyclase is an enzymatic modifier of the CD47- SIRPα axis and a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 612-619, 10.1038/s41591-019-0356-z.

- Louise W. Treffers; Xi Wen Zhao; Joris Van Der Heijden; Sietse Q. Nagelkerke; Dieke J. Van Rees; Patricia Gonzalez; Judy Geissler; Paul Verkuijlen; Michel Van Houdt; Martin De Boer; et al. Genetic variation of human neutrophil Fcγ receptors and SIRPα in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity towards cancer cells. European Journal of Immunology 2017, 48, 344-354, 10.1002/eji.201747215.

- Deborah Hatherley; Susan Lea; Steven Johnson; A. Neil Barclay; Polymorphisms in the Human Inhibitory Signal-regulatory Protein α Do Not Affect Binding to Its Ligand CD47. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 10024-10028, 10.1074/jbc.m114.550558.

- Xi Wen Zhao; Ellen M. van Beek; Karin Schornagel; Hans Van der Maaden; Michel Van Houdt; Marielle A. Otten; Pascal Finetti; Marjolein Van Egmond; Takashi Matozaki; Georg Kraal; et al. CD47–signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) interactions form a barrier for antibody-mediated tumor cell destruction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 18342-18347, 10.1073/pnas.1106550108.

- Annemiek van Spriel; Jeanette Leusen; Marjolein Van Egmond; Henry B. P. M. Dijkman; Karel J. M. Assmann; Tanya N. Mayadas; Jan G. J. Van De Winkel; Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) is essential for Fc receptor–mediated neutrophil cytotoxicity and immunologic synapse formation. Blood 2001, 97, 2478-2486, 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2478.

- Meghan A. Morrissey; Nadja Kern; Ronald D. Vale; CD47 Ligation Repositions the Inhibitory Receptor SIRPA to Suppress Integrin Activation and Phagocytosis. Immunity 2020, 53, 290-302.e6, 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.008.

- Richard K. Tsai; Dennis E. Discher; Inhibition of “self” engulfment through deactivation of myosin-II at the phagocytic synapse between human cells. Journal of Cell Biology 2008, 180, 989-1003, 10.1083/jcb.200708043.

- Hanke L. Matlung; Liane Babes; Xi Wen Zhao; Michel van Houdt; Louise W. Treffers; Dieke J. van Rees; Katka Franke; Karin Schornagel; Paul Verkuijlen; Hans Janssen; et al. Neutrophils Kill Antibody-Opsonized Cancer Cells by Trogoptosis. Cell Reports 2018, 23, 3946-3959.e6, 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.082.

- Alexei Kharitonenkov; Zhengjun Chen; Irmi Sures; Hongyang Wang; James Schilling; Axel Ullrich; A family of proteins that inhibit signalling through tyrosine kinase receptors. Nature 1997, 386, 181-186, 10.1038/386181a0.

- Per-Arne Oldenborg; Hattie D. Gresham; Frederik P. Lindberg; Cd47-Signal Regulatory Protein α (Sirpα) Regulates Fcγ and Complement Receptor–Mediated Phagocytosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2001, 193, 855-862, 10.1084/jem.193.7.855.

- Ulrike Lorenz; SHP-1 and SHP-2 in T cells: two phosphatases functioning at many levels. Immunological Reviews 2009, 228, 342-359, 10.1111/j.1600-065x.2008.00760.x.

- Louise W. Treffers; Toine Ten Broeke; Thies Rösner; J. H. Marco Jansen; Michel van Houdt; Steffen Kahle; Karin Schornagel; Paul J.J.H. Verkuijlen; Jan M. Prins; Katka Franke; et al. IgA-Mediated Killing of Tumor Cells by Neutrophils Is Enhanced by CD47–SIRPα Checkpoint Inhibition. Cancer Immunology Research 2020, 8, 120-130, 10.1158/2326-6066.cir-19-0144.

- Eun-Ju Kim; Kyoungho Suk; Won-Ha Lee; SHPS-1 and a synthetic peptide representing its ITIM inhibit the MyD88, but not TRIF, pathway of TLR signaling through activation of SHP and PI3K in THP-1 cells. Inflammation Research 2013, 62, 377-386, 10.1007/s00011-013-0589-0.

- André Veillette; Eric Thibaudeau; Sylvain Latour; High Expression of Inhibitory Receptor SHPS-1 and Its Association with Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase SHP-1 in Macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, 22719-22728, 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22719.

- Katka Franke; Saravanan Y. Pillai; Mark Hoogenboezem; Marion J. J. Gijbels; Hanke L. Matlung; Judy Geissler; Hugo Olsman; Chantal Pottgens; Patrick J. Van Gorp; Maria Ozsvar-Kozma; et al. SIRPα on Mouse B1 Cells Restricts Lymphoid Tissue Migration and Natural Antibody Production. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 570963, 10.3389/fimmu.2020.570963.

- D Cooper; F P Lindberg; J R Gamble; E J Brown; M A Vadas; Transendothelial migration of neutrophils involves integrin-associated protein (CD47).. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1995, 92, 3978-3982, 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3978.

- C A Parkos; S P Colgan; T W Liang; A Nusrat; A E Bacarra; D K Carnes; J L Madara; CD47 mediates post-adhesive events required for neutrophil migration across polarized intestinal epithelia.. Journal of Cell Biology 1996, 132, 437-450, 10.1083/jcb.132.3.437.

- Frederik P. Lindberg; Daniel C. Bullard; Tony E. Caver; Hattie D. Gresham; Arthur L. Beaudet; Eric J. Brown; Decreased Resistance to Bacterial Infection and Granulocyte Defects in IAP-Deficient Mice. Science 1996, 274, 795-798, 10.1126/science.274.5288.795.

- Sanne M. Meinderts; Per-Arne Oldenborg; Boukje M. Beuger; Thomas R. L. Klei; Johanna Johansson; Taco W. Kuijpers; Takashi Matozaki; Elise J. Huisman; Masja de Haas; Timo K. Van Den Berg; et al. Human and murine splenic neutrophils are potent phagocytes of IgG-opsonized red blood cells. Blood Advances 2017, 1, 875-886, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017004671.

- Yuan Liu; Didier Merlin; Stephanie L. Burst; Mildred Pochet; James L. Madara; Charles A. Parkos; The Role of CD47 in Neutrophil Transmigration. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 40156-40166, 10.1074/jbc.m104138200.

- Ke Zen; Yuan Liu; Role of different protein tyrosine kinases in fMLP-induced neutrophil transmigration. Immunobiology 2008, 213, 13-23, 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.07.001.

- Yuan Liu; Hans-Jörg Bühring; Ke Zen; Stephanie L. Burst; Frederick J. Schnell; Ifor R. Williams; Charles A. Parkos; Signal Regulatory Protein (SIRPα), a Cellular Ligand for CD47, Regulates Neutrophil Transmigration. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 10028-10036, 10.1074/jbc.m109720200.

- Yuan Liu; Miriam B. O’Connor; Kenneth J. Mandell; Ke Zen; Axel Ullrich; Hans-Jörg Bühring; Charles A. Parkos; Peptide-Mediated Inhibition of Neutrophil Transmigration by Blocking CD47 Interactions with Signal Regulatory Protein α. The Journal of Immunology 2004, 172, 2578-2585, 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2578.

- Julian Alvarez-Zarate; Hanke L. Matlung; Takashi Matozaki; Taco W. Kuijpers; Isabelle Maridonneau-Parini; Timo K. Van Den Berg; Regulation of Phagocyte Migration by Signal Regulatory Protein-Alpha Signaling. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0127178, 10.1371/journal.pone.0127178.

- Per-Arne Oldenborg; Alex Zheleznyak; Yi-Fu Fang; Carl F. Lagenaur; Hattie D. Gresham; Frederik P. Lindberg; Role of CD47 as a Marker of Self on Red Blood Cells. Science 2000, 288, 2051-2054, 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051.

- Tomomi Ishikawa-Sekigami; Yoriaki Kaneko; Hideki Okazawa; Takeshi Tomizawa; Jun Okajo; Yasuyuki Saito; Chie Okuzawa; Minako Sugawara-Yokoo; Uichi Nishiyama; Hiroshi Ohnishi; et al. SHPS-1 promotes the survival of circulating erythrocytes through inhibition of phagocytosis by splenic macrophages. Blood 2006, 107, 341-348, 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1896.

- Mattias Olsson; Pierre Bruhns; William A. Frazier; Jeffrey V. Ravetch; Per-Arne Oldenborg; Platelet homeostasis is regulated by platelet expression of CD47 under normal conditions and in passive immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2005, 105, 3577-3582, 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2980.

- Takuji Yamao; Tetsuya Noguchi; Osamu Takeuchi; Uichi Nishiyama; Haruhiko Morita; Tetsuya Hagiwara; Hironori Akahori; Takashi Kato; Kenjiro Inagaki; Hideki Okazawa; et al. Negative Regulation of Platelet Clearance and of the Macrophage Phagocytic Response by the Transmembrane Glycoprotein SHPS-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 39833-39839, 10.1074/jbc.m203287200.

- Bruce R. Blazar; Frederik P. Lindberg; Elizabeth Ingulli; Angela Panoskaltsis-Mortari; Per-Arne Oldenborg; Koho Iizuka; Wayne M. Yokoyama; Patricia A. Taylor; Cd47 (Integrin-Associated Protein) Engagement of Dendritic Cell and Macrophage Counterreceptors Is Required to Prevent the Clearance of Donor Lymphohematopoietic Cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2001, 194, 541-550, 10.1084/jem.194.4.541.

- Hui Wang; Maria Lucia Madariaga; Shumei Wang; Nico Van Rooijen; Per-Arne Oldenborg; Yong-Guang Yang; Lack of CD47 on nonhematopoietic cells induces split macrophage tolerance to CD47 null cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 13744-13749, 10.1073/pnas.0702881104.

- Katsuto Takenaka; Tatiana K Prasolava; Jean Wang; Steven M Mortin-Toth; Sam Khalouei; Olga I Gan; John Dick; Jayne S Danska; Polymorphism in Sirpa modulates engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nature Immunology 2007, 8, 1313-1323, 10.1038/ni1527.

- Timo K. Van Den Berg; C. Ellen van der Schoot; Innate immune ‘self’ recognition: a role for CD47–SIRPα interactions in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Trends in Immunology 2008, 29, 203-206, 10.1016/j.it.2008.02.004.

- Lai Shan Kwong; Marion H. Brown; A. Neil Barclay; Deborah Hatherley; Signal‐regulatory protein α from the NOD mouse binds human CD 47 with an exceptionally high affinity – implications for engraftment of human cells. Immunology 2014, 143, 61-67, 10.1111/imm.12290.

- Takuji Yamauchi; Katsuto Takenaka; Shingo Urata; Takahiro Shima; Yoshikane Kikushige; Takahito Tokuyama; Chika Iwamoto; Mariko Nishihara; Hiromi Iwasaki; Toshihiro Miyamoto; et al. Polymorphic Sirpa is the genetic determinant for NOD-based mouse lines to achieve efficient human cell engraftment. Blood 2013, 121, 1316-1325, 10.1182/blood-2012-06-440354.

- Mark P. Chao; Ash A. Alizadeh; Chad Tang; June H. Myklebust; Bindu Varghese; Saar Gill; Max Jan; Adriel C. Cha; Charles K. Chan; Brent T. Tan; et al. Anti-CD47 Antibody Synergizes with Rituximab to Promote Phagocytosis and Eradicate Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cell 2010, 142, 699-713, 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044.

- Fangqiu Fu; Yang Zhang; Zhendong Gao; Yue Zhao; Zhexu Wen; Han Han; Yuan Li; Hong Hu; Haiquan Chen; Combination of CD47 and CD68 expression predicts survival in eastern-Asian patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2021, 147, 739-747, 10.1007/s00432-020-03477-3.

- A. Neil Barclay; Timo K. Van Den Berg; The Interaction Between Signal Regulatory Protein Alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: Structure, Function, and Therapeutic Target. Annual Review of Immunology 2014, 32, 25-50, 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120142.

- Kipp Weiskopf; Nadine S. Jahchan; Peter Schnorr; Sandra Cristea; Aaron Ring; Roy L. Maute; Anne K. Volkmer; Jens-Peter Volkmer; Jie Liu; Jing Shan Lim; et al. CD47-blocking immunotherapies stimulate macrophage-mediated destruction of small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2016, 126, 2610-2620, 10.1172/jci81603.

- Feng Li; Bingke Lv; Yang Liu; Tian Hua; Jianbang Han; Chengmei Sun; Limin Xu; Zhongfei Zhang; Zhiming Feng; Yingqian Cai; et al. Blocking the CD47-SIRPα axis by delivery of anti-CD47 antibody induces antitumor effects in glioma and glioma stem cells. OncoImmunology 2017, 7, e1391973, 10.1080/2162402x.2017.1391973.

- Stephen B. Willingham; Jens-Peter Volkmer; Andrew J. Gentles; Debashis Sahoo; Piero Dalerba; Siddhartha S. Mitra; Jian Wang; Humberto Contreras-Trujillo; Robin Martin; Justin D. Cohen; et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 6662-6667, 10.1073/pnas.1121623109.

- Badreddin Edris; Kipp Weiskopf; Irving L Weissman; Matt van de Rijn; Flipping the script on macrophages in leiomyosarcoma. OncoImmunology 2012, 1, 1202-1204, 10.4161/onci.20799.

- Ji-Feng Xu; Xiao-Hong Pan; Shui-Jun Zhang; Chen Zhao; Bin-Song Qiu; Hai-Feng Gu; Jian-Fei Hong; Li Cao; Yu Chen; Bing Xia; et al. CD47 blockade inhibits tumor progression human osteosarcoma in xenograft models. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 23662-23670, 10.18632/oncotarget.4282.

- Fei Liu; Miao Dai; Qinyang Xu; Xiaolu Zhu; Yang Zhou; Shuheng Jiang; Yahui Wang; Zhihong Ai; Li Ma; Yanli Zhang; et al. SRSF10-mediated IL1RAP alternative splicing regulates cervical cancer oncogenesis via mIL1RAP-NF-κB-CD47 axis. Oncogene 2018, 37, 2394-2409, 10.1038/s41388-017-0119-6.

- Mingzi Tan; Liancheng Zhu; Huiyu Zhuang; Yingying Hao; Song Gao; Shuice Liu; Qing Liu; Dawo Liu; Juanjuan Liu; Bei Lin; et al. Lewis Y antigen modified CD47 is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis and promotes early ovarian cancer metastasis.. American journal of cancer research 2015, 5, 2777-87, .

- Dieke J. van Rees; Maximilian Brinkhaus; Bart Klein; Paul Verkuijlen; Anton T.J. Tool; Karin Schornagel; Louise W. Treffers; Michel van Houdt; Arnon P. Kater; Gestur Vidarsson; et al. Sodium stibogluconate and CD47-SIRPα blockade overcome resistance of anti-CD20–opsonized B cells to neutrophil killing. Blood Advances 2022, 6, 2156-2166, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005367.

- Mark P. Chao; Chad Tang; Russell Pachynski; Robert Chin; Ravindra Majeti; Irving L. Weissman; Extranodal dissemination of non-Hodgkin lymphoma requires CD47 and is inhibited by anti-CD47 antibody therapy. Blood 2011, 118, 4890-4901, 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338020.

- Mark P. Chao; Chris H. Takimoto; Dong Dong Feng; Kelly McKenna; Phung Gip; Jie Liu; Jens-Peter Volkmer; Irving L. Weissman; Ravindra Majeti; Therapeutic Targeting of the Macrophage Immune Checkpoint CD47 in Myeloid Malignancies. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 9, 1380, 10.3389/fonc.2019.01380.

- Paula Martínez-Sanz; Arjan J. Hoogendijk; Paul J. J. H. Verkuijlen; Karin Schornagel; Robin van Bruggen; Timo K. Van Den Berg; Godelieve A. M. Tytgat; Katka Franke; Taco W. Kuijpers; Hanke L. Matlung; et al. CD47-SIRPα Checkpoint Inhibition Enhances Neutrophil-Mediated Killing of Dinutuximab-Opsonized Neuroblastoma Cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 4261, 10.3390/cancers13174261.

- Xi Wen Zhao; Taco W. Kuijpers; Timo K. Van Den Berg; Is targeting of CD47-SIRPα enough for treating hematopoietic malignancy?. Blood 2012, 119, 4333-4334, 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391367.

- Xi Wen Zhao; Hanke L. Matlung; Taco W. Kuijpers; Timo K. Van Den Berg; On the mechanism of CD47 targeting in cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, E2843-5, 10.1073/pnas.1209265109.

- Tracy C. Kuo; Amy Chen; Ons Harrabi; Jonathan T. Sockolosky; Anli Zhang; Emma Sangalang; Laura V. Doyle; Steven E. Kauder; Danielle Fontaine; Sangeetha Bollini; et al. Targeting the myeloid checkpoint receptor SIRPα potentiates innate and adaptive immune responses to promote anti-tumor activity. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2020, 13, 1-19, 10.1186/s13045-020-00989-w.

- Nan Guo Ring; Dietmar Herndler-Brandstetter; Kipp Weiskopf; Liang Shan; Jens-Peter Volkmer; Benson M. George; Melanie Lietzenmayer; Kelly M. McKenna; Tejaswitha J. Naik; Aaron McCarty; et al. Anti-SIRPα antibody immunotherapy enhances neutrophil and macrophage antitumor activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, E10578-E10585, 10.1073/pnas.1710877114.

- Louise W. Treffers; Michel Van Houdt; Christine W. Bruggeman; Marieke H. Heineke; Xi Wen Zhao; Joris Van Der Heijden; Sietse Q. Nagelkerke; Paul J. J. H. Verkuijlen; Judy Geissler; Suzanne Lissenberg-Thunnissen; et al. FcγRIIIb Restricts Antibody-Dependent Destruction of Cancer Cells by Human Neutrophils. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 9, 3124, 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03124.

- Gestur Vidarsson; Gillian Dekkers; Theo Rispens; IgG Subclasses and Allotypes: From Structure to Effector Functions. Frontiers in Immunology 2014, 5, 520-520, 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00520.

- Thies Rösner; Steffen Kahle; Francesca Montenegro; Hanke L. Matlung; J. H. Marco Jansen; Mitchell Evers; Frank Beurskens; Jeanette H.W. Leusen; Timo K. Van Den Berg; Thomas Valerius; et al. Immune Effector Functions of Human IgG2 Antibodies against EGFR. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2019, 18, 75-88, 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-18-0341.

- Sergey E Sedykh; Victor V Prinz; Valentina N Buneva; Georgy A Nevinsky; Bispecific antibodies: design, therapy, perspectives. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2018, ume 12, 195-208, 10.2147/dddt.s151282.

- Kaixin Du; Yulu Li; Juan Liu; Wei Chen; Zhizhong Wei; Yong Luo; Huisi Liu; Yonghe Qi; Fengchao Wang; Jianhua Sui; et al. A bispecific antibody targeting GPC3 and CD47 induced enhanced antitumor efficacy against dual antigen-expressing HCC. Molecular Therapy 2021, 29, 1572-1584, 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.01.006.

- Mark A. J. M. Hendriks; Emily M. Ploeg; Iris Koopmans; Isabel Britsch; Xiurong Ke; Douwe F. Samplonius; Wijnand Helfrich; Bispecific antibody approach for EGFR-directed blockade of the CD47-SIRPα “don’t eat me” immune checkpoint promotes neutrophil-mediated trogoptosis and enhances antigen cross-presentation. OncoImmunology 2020, 9, 1824323, 10.1080/2162402x.2020.1824323.

- Marcello Albanesi; David A. Mancardi; Friederike Jönsson; Bruno Iannascoli; Laurence Fiette; James Di Santo; Clifford A. Lowell; Pierre Bruhns; Neutrophils mediate antibody-induced antitumor effects in mice. Blood 2013, 122, 3160-3164, 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497446.

- Francisco J Hernandez-Ilizaliturri; Venkata Jupudy; Julie Ostberg; Ezogelin Oflazoglu; Amy Huberman; Elizabeth Repasky; Myron S Czuczman; Neutrophils contribute to the biological antitumor activity of rituximab in a non-Hodgkin's lymphoma severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model.. Clinical Cancer Research 2003, 9, 5866-5873, .

- William M. Siders; Jacqueline Shields; Carrie Garron; Yanping Hu; Paula Boutin; Srinivas Shankara; William Weber; Bruce Roberts; Johanne M. Kaplan; Involvement of neutrophils and natural killer cells in the anti-tumor activity of alemtuzumab in xenograft tumor models. Leukemia & Lymphoma 2010, 51, 1293-1304, 10.3109/10428191003777963.

- Eric F. Zhu; Shuning A. Gai; Cary F. Opel; Byron H. Kwan; Rishi Surana; Martin C. Mihm; Monique J. Kauke; Kelly Moynihan; Alessandro Angelini; Robert Williams; et al. Synergistic Innate and Adaptive Immune Response to Combination Immunotherapy with Anti-Tumor Antigen Antibodies and Extended Serum Half-Life IL-2. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 489-501, 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.004.

- Diane Tseng; Jens-Peter Volkmer; Stephen B. Willingham; Humberto Contreras-Trujillo; John W. Fathman; Nathaniel B. Fernhoff; Jun Seita; Matthew A. Inlay; Kipp Weiskopf; Masanori Miyanishi; et al. Anti-CD47 antibody–mediated phagocytosis of cancer by macrophages primes an effective antitumor T-cell response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 11103-11108, 10.1073/pnas.1305569110.

- Xiaojuan Liu; Yang Pu; Kyle R Cron; Liufu Deng; Justin Kline; William A. Frazier; Hairong Xu; Hua Peng; Yang-Xin Fu; Meng Michelle Xu; et al. CD47 blockade triggers T cell–mediated destruction of immunogenic tumors. Nature Medicine 2015, 21, 1209-1215, 10.1038/nm.3931.

- Tadahiko Yanagita; Yoji Murata; Daisuke Tanaka; Sei-Ichiro Motegi; Eri Arai; Edwin Widyanto Daniwijaya; Daisuke Hazama; Ken Washio; Yasuyuki Saito; Takenori Kotani; et al. Anti-SIRPα antibodies as a potential new tool for cancer immunotherapy. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e89140, 10.1172/jci.insight.89140.

- Rodney Cheng-En Hsieh; Sunil Krishnan; Ren-Chin Wu; Akash R. Boda; Arthur Liu; Michelle Winkler; Wen-Hao Hsu; Steven Hsesheng Lin; Mien-Chie Hung; Li-Chuan Chan; et al. ATR-mediated CD47 and PD-L1 up-regulation restricts radiotherapy-induced immune priming and abscopal responses in colorectal cancer. Science Immunology 2022, 7, eabl9330, 10.1126/sciimmunol.abl9330.

- Jonathan T. Sockolosky; Michael Dougan; Jessica R. Ingram; Chia Chi M. Ho; Monique J. Kauke; Steven C. Almo; Hidde L. Ploegh; K. Christopher Garcia; Durable antitumor responses to CD47 blockade require adaptive immune stimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, E2646-E2654, 10.1073/pnas.1604268113.

- Vanessa Gauttier; Sabrina Pengam; Justine Durand; Kevin Biteau; Caroline Mary; Aurore Morello; Mélanie Néel; Georgia Porto; Géraldine Teppaz; Virginie Thepenier; et al. Selective SIRPα blockade reverses tumor T cell exclusion and overcomes cancer immunotherapy resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2020, 130, 6109-6123, 10.1172/jci135528.

- Huanpeng Chen; Yuying Yang; Yuqing Deng; Fengjiao Wei; Qingyu Zhao; Yongqi Liu; Zhonghua Liu; Bolan Yu; Zhaofeng Huang; Delivery of CD47 blocker SIRPα-Fc by CAR-T cells enhances antitumor efficacy. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2022, 10, e003737, 10.1136/jitc-2021-003737.

- Jie Liu; Lijuan Wang; Feifei Zhao; Serena Tseng; Cyndhavi Narayanan; Lei Shura; Stephen Willingham; Maureen Howard; Susan Prohaska; Jens Volkmer; et al. Pre-Clinical Development of a Humanized Anti-CD47 Antibody with Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Potential. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0137345, 10.1371/journal.pone.0137345.

- Pierre Bruhns; Bruno Iannascoli; Patrick England; David A. Mancardi; Nadine Fernandez; Sylvie Jorieux; Marc Daëron; Specificity and affinity of human Fcγ receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood 2009, 113, 3716-3725, 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179754.

- Rosalynd Upton; Allison Banuelos; Dongdong Feng; Tanuka Biswas; Kevin Kao; Kelly McKenna; Stephen Willingham; Po Yi Ho; Benyamin Rosental; Michal Caspi Tal; et al. Combining CD47 blockade with trastuzumab eliminates HER2-positive breast cancer cells and overcomes trastuzumab tolerance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2026849118, 10.1073/pnas.2026849118.

- Branimir I. Sikic; Nehal Lakhani; Amita Patnaik; Sumit A. Shah; Sreenivasa R. Chandana; Drew Rasco; A. Dimitrios Colevas; Timothy O’Rourke; Sujata Narayanan; Kyriakos Papadopoulos; et al. First-in-Human, First-in-Class Phase I Trial of the Anti-CD47 Antibody Hu5F9-G4 in Patients With Advanced Cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019, 37, 946-953, 10.1200/jco.18.02018.

- Amer M. Zeidan; Daniel J. DeAngelo; Jeanne Palmer; Christopher S. Seet; Martin S. Tallman; Xin Wei; Heather Raymon; Priya Sriraman; Stephan Kopytek; Jan Philipp Bewersdorf; et al. Phase 1 study of anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody CC-90002 in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Annals of Hematology 2022, 101, 557-569, 10.1007/s00277-021-04734-2.

- Rama Krishna Narla; Hardik Modi; Lilly Wong; Mahan Abassian; Daniel Bauer; Pragnya Desai; Bonny Gaffney; Pilgrim Jackson; Jim Leisten; Jing Liu; et al. Abstract 4694: The humanized anti-CD47 monclonal antibody, CC-90002, has antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Research 2017, 77, 4694-4694, 10.1158/1538-7445.am2017-4694.

- Pau Abrisqueta; Juan-Manuel Sancho; Raul Cordoba; Daniel O. Persky; Msce Charalambos Andreadis; Mph Scott F. Huntington; Cecilia Carpio; Daniel Morillo Giles; Xin Wei; Ying Fei Li; et al. Anti-CD47 Antibody, CC-90002, in Combination with Rituximab in Subjects with Relapsed and/or Refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (R/R NHL). Blood 2019, 134, 4089-4089, 10.1182/blood-2019-125310.

- Haiqing Ni; Lei Cao; Zhihai Wu; Li Wang; Shuaixiang Zhou; Xiaoli Guo; Yarong Gao; Hua Jing; Min Wu; Yang Liu; et al. Combined strategies for effective cancer immunotherapy with a novel anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2021, 71, 353-363, 10.1007/s00262-021-02989-2.

- Nehal Lakhani; Marlana Orloff; Siqing Fu; Ying Liu; Yan Wang; Hui Zhou; Kedan Lin; Fang Liu; Shuling Yan; Amita Patnaik; et al. 295 First-in-human Phase I trial of IBI188, an anti-CD47 targeting monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphomas. Regular and young investigator award abstracts 2020, 8, A180, 10.1136/jitc-2020-sitc2020.0295.

- Jordan Berlin; Wael Harb; Alex Adjei; Yan Xing; Paul Swiecicki; Mahesh Seetharam; Lakshminarayanan Nandagopal; Ajay Gopal; Cong Xu; Yuan Meng; et al. 385 A first-in-human study of lemzoparlimab, a differentiated anti-CD47 antibody, in subjects with relapsed/refractory malignancy: initial monotherapy results. Regular and young investigator award abstracts 2020, 8, A233-A234, 10.1136/jitc-2020-sitc2020.0385.

- AmitKumar Mehta; Wael Harb; Claire Xu; Yuan Meng; Linda Lee; Vivian Yuan; Zhengyi Wang; Pengfei Song; Joan Huaqiong Shen; Ajay K Gopal; et al. Lemzoparlimab, a Differentiated Anti-CD47 Antibody in Combination with Rituximab in Relapsed and Refractory Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: Initial Clinical Results. Blood 2021, 138, 3542-3542, 10.1182/blood-2021-150606.

- Junyuan Qi; Jian Li; Bin Bin Jiang; Bo Jiang; Hongzhong Liu; Xinxin Cao; Meixiang Zhang; Yuan Meng; Xiaoyu Ma; Yingmin Jia; et al. A Phase I/IIa Study of Lemzoparlimab, a Monoclonal Antibody Targeting CD47, in Patients with Relapsed and/or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) and Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS): Initial Phase I Results. Blood 2020, 136, 30-31, 10.1182/blood-2020-134391.

- Penka S. Petrova; Natasja Nielsen Viller; Mark Wong; Xinli Pang; Gloria H. Y. Lin; Karen Dodge; Vien Chai; Hui Chen; Vivian Lee; Violetta House; et al. TTI-621 (SIRPαFc): A CD47-Blocking Innate Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor with Broad Antitumor Activity and Minimal Erythrocyte Binding. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 1068-1079, 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-16-1700.

- Gloria H. Y. Lin; Vien Chai; Vivian Lee; Karen Dodge; Tran Truong; Mark Wong; Lisa Johnson; Emma Linderoth; Xinli Pang; Jeff Winston; et al. TTI-621 (SIRPαFc), a CD47-blocking cancer immunotherapeutic, triggers phagocytosis of lymphoma cells by multiple polarized macrophage subsets. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187262, 10.1371/journal.pone.0187262.

- Stephen M. Ansell; Michael B. Maris; Alexander M. Lesokhin; Robert W. Chen; Ian W. Flinn; Ahmed Sawas; Mark D. Minden; Diego Villa; Mary-Elizabeth M. Percival; Anjali S. Advani; et al. Phase I Study of the CD47 Blocker TTI-621 in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Hematologic Malignancies. Clinical Cancer Research 2021, 27, 2190-2199, 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-3706.

- Christiane Querfeld; John A Thompson; Matthew H Taylor; Jennifer A DeSimone; Jasmine M Zain; Andrei R Shustov; Carolyn Johns; Sue McCann; Gloria H Y Lin; Penka S Petrova; et al. Intralesional TTI-621, a novel biologic targeting the innate immune checkpoint CD47, in patients with relapsed or refractory mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome: a multicentre, phase 1 study. The Lancet Haematology 2021, 8, e808-e817, 10.1016/s2352-3026(21)00271-4.

- Krish Patel; Radhakrishnan Ramchandren; Michael Maris; Alexander M. Lesokhin; Gottfried R. Von Keudell; Bruce D. Cheson; Jeff Zonder; Erlene K. Seymour; Tina Catalano; Gloria H. Y. Lin; et al. Investigational CD47-Blocker TTI-622 Shows Single-Agent Activity in Patients with Advanced Relapsed or Refractory Lymphoma: Update from the Ongoing First-in-Human Dose Escalation Study. Blood 2020, 136, 46-47, 10.1182/blood-2020-136607.

- Krish Patel; Jeffrey A. Zonder; Dahlia Sano; Michael Maris; Alexander Lesokhin; Gottfried von Keudell; Catherine Lai; Rod Ramchandren; Tina Catalano; Gloria H. Y. Lin; et al. CD47-Blocker TTI-622 Shows Single-Agent Activity in Patients with Advanced Relapsed or Refractory Lymphoma: Update from the Ongoing First-in-Human Dose Escalation Study. Blood 2021, 138, 3560-3560, 10.1182/blood-2021-153683.

- Kipp Weiskopf; Aaron M. Ring; Chia Chi M. Ho; Jens-Peter Volkmer; Aron M. Levin; Anne Kathrin Volkmer; Engin Özkan; Nathaniel B. Fernhoff; Matt van de Rijn; Irving L. Weissman; et al. Engineered SIRPα Variants as Immunotherapeutic Adjuvants to Anticancer Antibodies. Science 2013, 341, 88-91, 10.1126/science.1238856.

- Steven E. Kauder; Tracy C. Kuo; Ons Harrabi; Amy Chen; Emma Sangalang; Laura Doyle; Sony S. Rocha; Sangeetha Bollini; Bora Han; Janet Sim; et al. ALX148 blocks CD47 and enhances innate and adaptive antitumor immunity with a favorable safety profile. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0201832, 10.1371/journal.pone.0201832.

- Nehal J Lakhani; Laura Q M Chow; Justin F Gainor; Patricia LoRusso; Keun-Wook Lee; Hyun Cheol Chung; Jeeyun Lee; Yung-Jue Bang; Frank Stephen Hodi; Won Seog Kim; et al. Evorpacept alone and in combination with pembrolizumab or trastuzumab in patients with advanced solid tumours (ASPEN-01): a first-in-human, open-label, multicentre, phase 1 dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. The Lancet Oncology 2021, 22, 1740-1751, 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00584-2.

- Timo K. Van Den Berg; Thomas Valerius; Myeloid immune-checkpoint inhibition enters the clinical stage. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2018, 16, 275-276, 10.1038/s41571-018-0155-3.

- Henry Chan; Christina Trout; David Mikolon; Preston Adams; Roberto Guzman; Gustavo Fenalti; Konstantinos Mavrommatis; Mahan Abbasian; Lawrence Dearth; Brian Fox; et al. Discovery and Preclinical Characterization of CC-95251, an Anti-SIRPα Antibody That Enhances Macrophage-Mediated Phagocytosis of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) Cells When Combined with Rituximab. Blood 2021, 138, 2271-2271, 10.1182/blood-2021-147262.

- Paolo Strati; Eliza Hawkes; Nilanjan Ghosh; Joseph M. Tuscano; Quincy Chu; Mary Ann Anderson; Amar Patel; Michael R. Burgess; Kristen Hege; Sapna Chhagan; et al. Interim Results from the First Clinical Study of CC-95251, an Anti-Signal Regulatory Protein-Alpha (SIRPα) Antibody, in Combination with Rituximab in Patients with Relapsed and/or Refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (R/R NHL). Blood 2021, 138, 2493-2493, 10.1182/blood-2021-147292.

- Stéphane Champiat; Philippe A. Cassier; Nuria Kotecki; Iphigenie Korakis; Armelle Vinceneux; Christiane Jungels; Jon Blatchford; Mabrouk M. Elgadi; Nicole Clarke; Claudia Fromond; et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and preliminary biomarker data of first-in-class BI 765063, a selective SIRPα inhibitor: Results of monotherapy dose escalation in phase 1 study in patients with advanced solid tumors.. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021, 39, 2623-2623, 10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.2623.

- Akemi Irie; Akira Yamauchi; Keiichi Kontani; Minoru Kihara; Dage Liu; Yukako Shirato; Masako Seki; Nozomu Nishi; Takanori Nakamura; Hiroyasu Yokomise; et al. Galectin-9 as a Prognostic Factor with Antimetastatic Potential in Breast Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2005, 11, 2962-2968, 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-04-0861.

- Natasha Ustyanovska Avtenyuk; Ghizlane Choukrani; Emanuele Ammatuna; Toshiro Niki; Ewa Cendrowicz; Harm Jan Lourens; Gerwin Huls; Valerie R. Wiersma; Edwin Bremer; Galectin-9 Triggers Neutrophil-Mediated Anticancer Immunity. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 66, 10.3390/biomedicines10010066.

- Bryan Oronsky; Xiaoning Guo; Xiaohui Wang; Pedro Cabrales; David Sher; Lou Cannizzo; Bob Wardle; Nacer Abrouk; Michelle Lybeck; Scott Caroen; et al. Discovery of RRx-001, a Myc and CD47 Downregulating Small Molecule with Tumor Targeted Cytotoxicity and Healthy Tissue Cytoprotective Properties in Clinical Development. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 64, 7261-7271, 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00599.

- Bryan Oronsky; Pedro Cabrales; Scott Caroen; Xiaoning Guo; Curtis Scribner; Arnold Oronsky; Tony R. Reid; RRx-001, a downregulator of the CD47- SIRPα checkpoint pathway, does not cause anemia or thrombocytopenia. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology 2021, 17, 355-357, 10.1080/17425255.2021.1876025.

- Pedro Cabrales; RRx-001 Acts as a Dual Small Molecule Checkpoint Inhibitor by Downregulating CD47 on Cancer Cells and SIRP-α on Monocytes/Macrophages. Translational Oncology 2019, 12, 626-632, 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.12.001.

- Tony Reid; Bryan Oronsky; Jan Scicinski; Curt L Scribner; Susan J Knox; Shoucheng Ning; Donna M Peehl; Ron Korn; Meaghan Stirn; Corey A Carter; et al. Safety and activity of RRx-001 in patients with advanced cancer: a first-in-human, open-label, dose-escalation phase 1 study. The Lancet Oncology 2015, 16, 1133-1142, 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00089-3.

- Yusuke Tomita; Bryan Oronsky; Nacer Abrouk; Pedro Cabrales; Tony R. Reid; Min-Jung Lee; Akira Yuno; Jonathan Baker; Sunmin Lee; Jane B. Trepel; et al. In small cell lung cancer patients treated with RRx-001, a downregulator of CD47, decreased expression of PD-L1 on circulating tumor cells significantly correlates with clinical benefit. Translational Lung Cancer Research 2021, 10, 274-278, 10.21037/tlcr-20-359.

- Deepika Sharma Das; Arghya Ray; Abhishek Das; Yan Song; Z Tian; Bryan Oronsky; Paul Richardson; Jan Scicinski; Dharminder Chauhan; Kenneth C. Anderson; et al. A novel hypoxia-selective epigenetic agent RRx-001 triggers apoptosis and overcomes drug resistance in multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 2016, 30, 2187-2197, 10.1038/leu.2016.96.

- Bryan Oronsky; Tony R Reid; Christopher Larson; Scott Caroen; Mary Quinn; Erica Burbano; Gina Varner; Bennett Thilagar; Bradley Brown; Angelique Coyle; et al. REPLATINUM Phase III randomized study: RRx-001 + platinum doublet versus platinum doublet in third-line small cell lung cancer. Future Oncology 2019, 15, 3427-3433, 10.2217/fon-2019-0317.

- Zhiqiang Wu; Linjun Weng; Tengbo Zhang; Hongling Tian; Lan Fang; Hongqi Teng; Wen Zhang; Jing Gao; Yun Hao; Yaxu Li; et al. Identification of Glutaminyl Cyclase isoenzyme isoQC as a regulator of SIRPα-CD47 axis. Cell Research 2019, 29, 502-505, 10.1038/s41422-019-0177-0.

- Niklas Baumann; Thies Rösner; J. H. Marco Jansen; Chilam Chan; Klara Marie Eichholz; Katja Klausz; Dorothee Winterberg; Kristina Müller; Andreas Humpe; Renate Burger; et al. Enhancement of epidermal growth factor receptor antibody tumor immunotherapy by glutaminyl cyclase inhibition to interfere with CD47/signal regulatory protein alpha interactions. Cancer Science 2021, 112, 3029-3040, 10.1111/cas.14999.

- Teresa L. Burgess; Joshua D. Amason; Jeffrey S. Rubin; Damien Y. Duveau; Laurence Lamy; David D. Roberts; Catherine L. Farrell; James Inglese; Craig J. Thomas; Thomas W. Miller; et al. A homogeneous SIRPα-CD47 cell-based, ligand-binding assay: Utility for small molecule drug development in immuno-oncology. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0226661, 10.1371/journal.pone.0226661.

- Mitchell Evers; Thies Rösner; Anna Duenkel; J. H. Marco Marco Jansen; Niklas Baumann; Toine Ten Broeke; Maaike Nederend; Klara Eichholz; Katja Klausz; Karli Reiding; et al. The selection of variable regions affects effector mechanisms of IgA antibodies against CD20. Blood Advances 2021, 5, 3807-3820, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004598.

- Zhiqiang Li; Xuemei Gu; Danni Rao; Meiling Lu; Jing Wen; Xinyan Chen; Hongbing Wang; Xianghuan Cui; Wenwen Tang; Shilin Xu; et al. Luteolin promotes macrophage-mediated phagocytosis by inhibiting CD47 pyroglutamation. Translational Oncology 2021, 14, 101129, 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101129.

- Paolo Strati; Eliza Hawkes; Nilanjan Ghosh; Joseph M. Tuscano; Quincy Chu; Mary Ann Anderson; Amar Patel; Michael R. Burgess; Kristen Hege; Sapna Chhagan; et al. Interim Results from the First Clinical Study of CC-95251, an Anti-Signal Regulatory Protein-Alpha (SIRPα) Antibody, in Combination with Rituximab in Patients with Relapsed and/or Refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (R/R NHL). Blood 2021, 138, 2493-2493, 10.1182/blood-2021-147292.