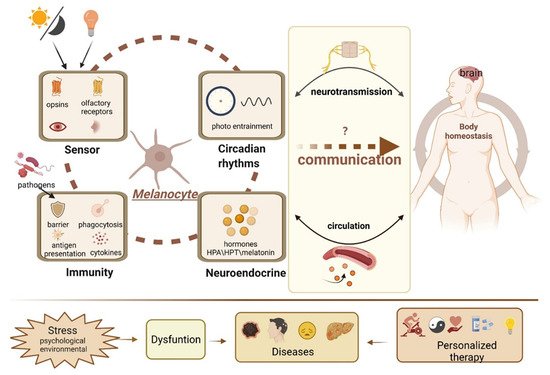

黑素细胞产生黑色素,以保护皮肤免受UV-B辐射。尽管如此,它们的功能范围远远超出了它们作为黑色素生产工厂的众所周知的作用。黑素细胞被认为是感觉和计算细胞。黑素细胞产生的神经递质,神经肽和其他激素使它们成为皮肤精心策划和复杂的神经内分泌网络的一部分,抵消环境压力源。黑素细胞也可以主动介导表皮免疫反应。黑素细胞具有类似于眼睛和鼻子的异位感觉系统,可以感知光和气味。此外,黑素细胞也被证明位于内耳,大脑和心脏等内部部位,这些部位不受阳光刺激。

- melanocytes

- neuroendocrinology

- circadian rhythm

- photoentrainment

- homeostasis

- regulatory network

- sensory functions

- opsins

- extracutaneous pigment cell

- innate immunity

1. Introduction

2. Melanocytes and the Endocrine System

2.1. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis Homolog

2.2. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis (HPT) Homolog

2.3. Serotoninergic/Melatoninergic System

2.4. Other Neuroendocrine Activities

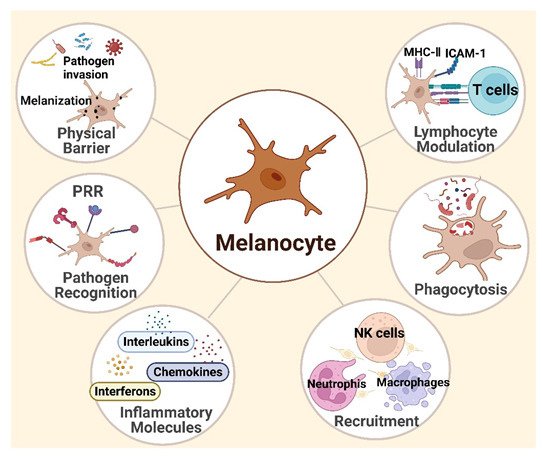

3. Melanocytes and Skin Immunity

3.1. Melanocytes Are Functional Immune Sentinel Cells in the Skin

3.2. Innate Immune Responses

3.3. Adaptive Immunity

4. Melanocytes and the Sensory System

4.1. The Melanocyte Photosensory System

4.1.1. Phototransduction

4.1.2. Circadian Photoentrainment

| Opsin | Species | Potential Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPN1 | Mouse | Not shown | [146] |

| Human | Not shown | [127][129] | |

| OPN2 | Mouse | Mediate UVA-induced immediate pigment darkening | [126][135][147] |

| Regulate clock genes and melanogenesis responding to white light | |||

| Human | Mediate UVR-induced early melanin synthesis | [127][128][129] | |

| OPN3 | Human | Sense blue light and regulate long-lasting hyperpigmentation | [129][130][131][132][133] |

| Negatively regulate pigmentation through interaction with MC1R | |||

| Regulate the survival of melanocytes | |||

| OPN4 | Mouse | Mediate UVA-induced immediate pigment darkening | [146][147][148] |

| Regulate clock genes and melanogenesis responding to white light | |||

| Mediate UVA-related proliferation and apoptosis | |||

| Mediate thermal activation of clock genes | |||

| Human | Photoreceptor of blue light | [124] | |

| OPN5 | Mouse | Local circadian photoentrainment | [145] |

| Human | Regulate UVR-induced melanogenesis |

4.2. The Melanocyte Olfactory System

5. Melanocytes Outside the Skin

5.1. 心脏

5.2. 耳朵

其他器官

| 位置 | 功能 | 参考 |

|---|---|---|

| 心 | 支持心脏瓣膜的刚度和机械性能 | [172][173][174][175][176] |

| 降低 ROS | ||

| 调节电气和结构改造 | ||

| 维持内淋巴潜力 | ||

| 调节人工耳蜗发育 | ||

| 稳定纹状体内液体-血液屏障 | ||

| 防止噪音和耳毒性 | ||

| 内耳 | 降低 ROS | [180][181][182][190][191][193] |

| 眼睛 | 眼睛色素沉着和紫外线防护 | [189][194][198][199] |

| 支持脉络膜的正常脉管系统 | ||

| 诱导趋化因子分泌和单核细胞迁移 | ||

| 皮脂腺 | 可能是黑素细胞干细胞的来源 | [200] |

| 脑 | 神经内分泌和解毒 | [195] |

| 脂肪的 | 减轻氧化应激和炎症 | [196][197] |

最近的证据表明,人们对皮肤黑素细胞的胚胎起源有了新的认识,因为这些色素细胞不仅起源于迁移神经嵴细胞,还来自神经来源的多能施旺细胞前体(SCP)。[201][202].此外,这种皮肤黑素细胞的SCP依赖性起源在进化过程中在鱼类,鸟类和哺乳动物中得到了保护。[201][202][203][204].尽管如此,位于内耳,脑膜,心脏和其他部位的皮外黑素细胞的起源一直是一个“神秘”的问题,迷人的科学家。最近,通过谱系追踪策略与3D可视化相结合,逐渐解决了这一长期存在的问题,揭示了周围神经衍生的SCP是皮外黑素细胞的基本细胞起源。[204][205].这种皮外黑素细胞的起源可能与它们的局部特化及其非常规作用有关。但这使我们对黑素细胞真正作用的理解复杂化。[204].因此,皮肤外的黑素细胞也表现出黑色素合成以外的迷人功能,进一步探索黑色素细胞的胚胎发育将导致对特定皮肤疾病的更好理解,并设想未来的预防和治疗策略。[204].

6. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11132082

References

- Lin, J.Y.; Fisher, D.E. Melanocyte biology and skin pigmentation. Nature 2007, 445, 843–850.

- Sulaimon, S.S.; Kitchell, B.E. The biology of melanocytes. Vet. Dermatol. 2003, 14, 57–65.

- Cordero, R.J.B.; Casadevall, A. Melanin. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R142–R143.

- ElObeid, A.S.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Abdelhalim, M.A.K.; Haseeb, A.M. Pharmacological Properties of Melanin and its Function in Health. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 120, 515–522.

- Plonka, P.M.; Passeron, T.; Brenner, M.; Tobin, D.J.; Shibahara, S.; Thomas, A.; Slominski, A.; Kadekaro, A.L.; Hershkovitz, D.; Peters, E.; et al. What are melanocytes really doing all day long…? Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 799–819.

- Slominski, A.T.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Skobowiat, C.; Zbytek, B.; Slominski, R.M.; Steketee, J.D. Sensing the environment: Regulation of local and global homeostasis by the skin’s neuroendocrine system. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2012, 212, 1–115.

- Slominski, A.; Paus, R.; Schadendorf, D. Melanocytes as “sensory” and regulatory cells in the epidermis. J. Theor. Biol. 1993, 164, 103–120.

- Cichorek, M.; Wachulska, M.; Stasiewicz, A.; Tyminska, A. Skin melanocytes: Biology and development. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2013, 30, 30–41.

- Slominski, A. Neuroendocrine activity of the melanocyte. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 760–763.

- Alexopoulos, A.; Chrousos, G.P. Stress-related skin disorders. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2016, 17, 295–304.

- Phan, T.S.; Schink, L.; Mann, J.; Merk, V.M.; Zwicky, P.; Mundt, S.; Simon, D.; Kulms, D.; Abraham, S.; Legler, D.F.; et al. Keratinocytes control skin immune homeostasis through de novo-synthesized glucocorticoids. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe0337.

- Paus, R.; Arck, P. Neuroendocrine perspectives in alopecia areata: Does stress play a role? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1324–1326.

- Kotb El-Sayed, M.I.; Abd El-Ghany, A.A.; Mohamed, R.R. Neural and Endocrinal Pathobiochemistry of Vitiligo: Comparative Study for a Hypothesized Mechanism. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 197.

- Zhang, B.; Ma, S.; Rachmin, I.; He, M.; Baral, P.; Choi, S.; Goncalves, W.A.; Shwartz, Y.; Fast, E.M.; Su, Y.; et al. Hyperactivation of sympathetic nerves drives depletion of melanocyte stem cells. Nature 2020, 577, 676–681.

- Bocheva, G.; Slominski, R.M.; Slominski, A.T. Neuroendocrine Aspects of Skin Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2798.

- Theoharides, T.C.; Stewart, J.M.; Taracanova, A.; Conti, P.; Zouboulis, C.C. Neuroendocrinology of the skin. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2016, 17, 287–294.

- Leis, K.; Mazur, E.; Jablonska, M.J.; Kolan, M.; Galazka, P. Endocrine systems of the skin. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2019, 36, 519–523.

- Takeda, K.; Takahashi, N.H.; Shibahara, S. Neuroendocrine functions of melanocytes: Beyond the skin-deep melanin maker. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2007, 211, 201–221.

- Rousseau, K.; Kauser, S.; Pritchard, L.E.; Warhurst, A.; Oliver, R.L.; Slominski, A.; Wei, E.T.; Thody, A.J.; Tobin, D.J.; White, A. Proopiomelanocortin (POMC), the ACTH/melanocortin precursor, is secreted by human epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes and stimulates melanogenesis. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1844–1856.

- Spencer, J.D.; Schallreuter, K.U. Regulation of pigmentation in human epidermal melanocytes by functional high-affinity beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone/melanocortin-4 receptor signaling. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 1250–1258.

- Slominski, A. Identification of beta-endorphin, alpha-MSH and ACTH peptides in cultured human melanocytes, melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma cells by RP-HPLC. Exp. Dermatol. 1998, 7, 213–216.

- Bhm, M.; Metze, D.; Schulte, U.; Becher, E.; Luger, T.A.; Brzoska, T. Detection of melanocortin-1 receptor antigenicity on human skin cells in culture and in situ. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 8, 453–461.

- Farooqui, J.Z.; Medrano, E.E.; Abdel-Malek, Z.; Nordlund, J. The expression of proopiomelanocortin and various POMC-derived peptides in mouse and human skin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 680, 508–510.

- Slominski, A.; Ermak, G.; Hwang, J.; Chakraborty, A.; Mazurkiewicz, J.E.; Mihm, M. Proopiomelanocortin, corticotropin releasing hormone and corticotropin releasing hormone receptor genes are expressed in human skin. FEBS Lett. 1995, 374, 113–116.

- Slominski, A.; Baker, J.; Ermak, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Pawelek, J. Ultraviolet B stimulates production of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) by human melanocytes. FEBS Lett. 1996, 399, 175–176.

- Kono, M.; Nagata, H.; Umemura, S.; Kawana, S.; Osamura, R.Y. In situ expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) genes in human skin. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 2297–2299.

- Slominski, A.; Zbytek, B.; Szczesniewski, A.; Semak, I.; Kaminski, J.; Sweatman, T.; Wortsman, J. CRH stimulation of corticosteroids production in melanocytes is mediated by ACTH. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E701–E706.

- Ramot, Y.; Bohm, M.; Paus, R. Translational Neuroendocrinology of Human Skin: Concepts and Perspectives. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 60–74.

- Skobowiat, C.; Dowdy, J.C.; Sayre, R.M.; Tuckey, R.C.; Slominski, A. Cutaneous hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis homolog: Regulation by ultraviolet radiation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 301, E484–E493.

- Skobowiat, C.; Nejati, R.; Lu, L.; Williams, R.W.; Slominski, A.T. Genetic variation of the cutaneous HPA axis: An analysis of UVB-induced differential responses. Gene 2013, 530, 1–7.

- Slominski, A.T.; Slominski, R.M.; Raman, C. UVB stimulates production of enkephalins and other neuropeptides by skin-resident cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020425118.

- Jozic, I.; Stojadinovic, O.; Kirsner, R.S.F.; Tomic-Canic, M. Skin under the (Spot)-Light: Cross-Talk with the Central Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 1469–1471.

- Sato, H.; Nagashima, Y.; Chrousos, G.P.; Ichihashi, M.; Funasak, Y. The expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone in melanoma. Pigment. Cell Res. 2002, 15, 98–103.

- Kim, M.H.; Cho, D.; Kim, H.J.; Chong, S.J.; Lee, K.H.; Yu, D.S.; Park, C.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Cho, B.K.; Park, H.J. Investigation of the corticotropin-releasing hormone-proopiomelanocortin axis in various skin tumours. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 910–915.

- Eberle, A.N.; Rout, B.; Qi, M.B.; Bigliardi, P.L. Synthetic Peptide Drugs for Targeting Skin Cancer: Malignant Melanoma and Melanotic Lesions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 1797–1826.

- Kingo, K.; Aunin, E.; Karelson, M.; Philips, M.A.; Ratsep, R.; Silm, H.; Vasar, E.; Soomets, U.; Koks, S. Gene expression analysis of melanocortin system in vitiligo. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2007, 48, 113–122.

- Shaker, O.G.; Eltahlawi, S.M.; Tawfic, S.O.; Eltawdy, A.M.; Bedair, N.I. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and CRH receptor 1 gene expression in vitiligo. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 41, 734–740.

- Spencer, J.; Gibbons, N.; Rokos, H.; Peters, E.; Wood, J.; Schallreuter, K. Oxidative stress via hydrogen peroxide affects proopiomelanocortin peptides directly in the epidermis of patients with vitiligo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 411–420.

- Mancino, G.; Miro, C.; Di Cicco, E.; Dentice, M. Thyroid hormone action in epidermal development and homeostasis and its implications in the pathophysiology of the skin. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 1571–1579.

- Bodo, E.; Kany, B.; Gaspar, E.; Knuver, J.; Kromminga, A.; Ramot, Y.; Biro, T.; Tiede, S.; van Beek, N.; Poeggeler, B.; et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, a novel, locally produced modulator of human epidermal functions, is regulated by thyrotropin-releasing hormone and thyroid hormones. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1633–1642.

- Baldini, E.; Odorisio, T.; Sorrenti, S.; Catania, A.; Tartaglia, F.; Carbotta, G.; Pironi, D.; Rendina, R.; D’Armiento, E.; Persechino, S.; et al. Vitiligo and Autoimmune Thyroid Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 290.

- Slominski, A.; Wortsman, J.; Kohn, L.; Ain, K.B.; Venkataraman, G.M.; Pisarchik, A.; Chung, J.H.; Giuliani, C.; Thornton, M.; Slugocki, G.; et al. Expression of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis related genes in the human skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2002, 119, 1449–1455.

- Gaspar, E.; Nguyen-Thi, K.T.; Hardenbicker, C.; Tiede, S.; Plate, C.; Bodo, E.; Knuever, J.; Funk, W.; Biro, T.; Paus, R. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone selectively stimulates human hair follicle pigmentation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 2368–2377.

- Sandru, F.; Carsote, M.; Albu, S.E.; Dumitrascu, M.C.; Valea, A. Vitiligo and chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 127–130.

- Liu, M.; Murphy, E.; Amerson, E.H. Rethinking screening for thyroid autoimmunity in vitiligo. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 1278–1280.

- Li, D.; Liang, G.; Calderone, R.; Bellanti, J.A. Vitiligo and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: Autoimmune diseases linked by clinical presentation, biochemical commonality, and autoimmune/oxidative stress-mediated toxicity pathogenesis. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 128, 69–75.

- Ellerhorst, J.A.; Naderi, A.A.; Johnson, M.K.; Pelletier, P.; Prieto, V.G.; Diwan, A.H.; Johnson, M.M.; Gunn, D.C.; Yekell, S.; Grimm, E.A. Expression of thyrotropin-releasing hormone by human melanoma and nevi. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 5531–5536.

- Ellerhorst, J.A.; Sendi-Naderi, A.; Johnson, M.K.; Cooke, C.P.; Dang, S.M.; Diwan, A.H. Human melanoma cells express functional receptors for thyroid-stimulating hormone. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, 1269–1277.

- Ursu, H. Functional TSH Receptors, Malignant Melanomas and Subclinical Hypothyroidism. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2012, 1, 208.

- Hou, P.; Liu, D.; Ji, M.; Liu, Z.; Engles, J.M.; Wahl, R.L.; Xing, M. Induction of thyroid gene expression and radioiodine uptake in melanoma cells: Novel therapeutic implications. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6200.

- Scheau, C.; Draghici, C.; Ilie, M.A.; Lupu, M.; Caruntu, C. Neuroendocrine Factors in Melanoma Pathogenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2277.

- Sevilla, A.; Chéret, J.; Slominski, R.M.; Slominski, A.T.; Paus, R. Revisiting the role of melatonin in human melanocyte physiology: A skin context perspective. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 72, e12790.

- Rusanova, I.; Martinez-Ruiz, L.; Florido, J.; Rodriguez-Santana, C.; Guerra-Librero, A.; Acuna-Castroviejo, D.; Escames, G. Protective Effects of Melatonin on the Skin: Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4948.

- Kim, T.K.; Kleszczynski, K.; Janjetovic, Z.; Sweatman, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, W.; Reiter, R.J.; Fischer, T.W.; Slominski, A.T. Metabolism of melatonin and biological activity of intermediates of melatoninergic pathway in human skin cells. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 2742–2755.

- Slominski, A.; Pisarchik, A.; Semak, I.; Sweatman, T.; Wortsman, J.; Szczesniewski, A.; Slugocki, G.; McNulty, J.; Kauser, S.; Tobin, D.J.; et al. Serotoninergic and melatoninergic systems are fully expressed in human skin. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 896–898.

- Slominski, A.T.; Kim, T.K.; Kleszczynski, K.; Semak, I.; Janjetovic, Z.; Sweatman, T.; Skobowiat, C.; Steketee, J.D.; Lin, Z.; Postlethwaite, A.; et al. Characterization of serotonin and N-acetylserotonin systems in the human epidermis and skin cells. J. Pineal Res. 2020, 68, e12626.

- Slominski, A.; Pisarchik, A.; Johansson, O.; Jing, C.; Semak, I.; Slugocki, G.; Wortsman, J. Tryptophan hydroxylase expression in human skin cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Basis Dis. 2003, 1639, 80–86.

- Kim, T.K.; Lin, Z.; Tidwell, W.J.; Li, W.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and its metabolites accumulate in the human epidermis in vivo and inhibit proliferation and tyrosinase activity in epidermal melanocytes in vitro. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2015, 404, 1–8.

- Slominski, A.; Semak, I.; Pisarchik, A.; Sweatman, T.; Szczesniewski, A.; Wortsman, J. Conversion ofL-tryptophan to serotonin and melatonin in human melanoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2002, 511, 102–106.

- Skobowiat, C.; Brozyna, A.A.; Janjetovic, Z.; Jeayeng, S.; Oak, A.S.W.; Kim, T.K.; Panich, U.; Reiter, R.J.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and its derivatives counteract the ultraviolet B radiation-induced damage in human and porcine skin ex vivo. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12501.

- Kleszczynski, K.; Kim, T.K.; Bilska, B.; Sarna, M.; Mokrzynski, K.; Stegemann, A.; Pyza, E.; Reiter, R.J.; Steinbrink, K.; Bohm, M.; et al. Melatonin exerts oncostatic capacity and decreases melanogenesis in human MNT-1 melanoma cells. J. Pineal Res. 2019, 67, e12610.

- Perdomo, J.; Quintana, C.; Gonzalez, I.; Hernandez, I.; Rubio, S.; Loro, J.F.; Reiter, R.J.; Estevez, F.; Quintana, J. Melatonin Induces Melanogenesis in Human SK-MEL-1 Melanoma Cells Involving Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 and Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4970.

- Janjetovic, Z.; Nahmias, Z.P.; Hanna, S.; Jarrett, S.G.; Kim, T.K.; Reiter, R.J.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and its metabolites ameliorate ultraviolet B-induced damage in human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 90–102.

- Janjetovic, Z.; Jarrett, S.G.; Lee, E.F.; Duprey, C.; Reiter, R.J.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and its metabolites protect human melanocytes against UVB-induced damage: Involvement of NRF2-mediated pathways. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 1274.

- Dong, K.; Goyarts, E.; Rella, A.; Pelle, E.; Wong, Y.H.; Pernodet, N. Age Associated Decrease of MT-1 Melatonin Receptor in Human Dermal Skin Fibroblasts Impairs Protection Against UV-Induced DNA Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 326.

- Gillbro, J.M.; Marles, L.K.; Hibberts, N.A.; Schallreuter, K.U. Autocrine catecholamine biosynthesis and the beta-adrenoceptor signal promote pigmentation in human epidermal melanocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 123, 346–353.

- Sivamani, R.K.; Porter, S.M.; Isseroff, R.R. An epinephrine-dependent mechanism for the control of UV-induced pigmentation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 784–787.

- Choi, M.E.; Yoo, H.; Lee, H.R.; Moon, I.J.; Lee, W.J.; Song, Y.; Chang, S.E. Carvedilol, an Adrenergic Blocker, Suppresses Melanin Synthesis by Inhibiting the cAMP/CREB Signaling Pathway in Human Melanocytes and Ex Vivo Human Skin Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8796.

- Slominski, A.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Pawelek, J. L-tyrosine and L-dihydroxyphenylalanine as hormone-like regulators of melanocyte functions. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2012, 25, 14–27.

- Ono, K.; Viet, C.T.; Ye, Y.; Dang, D.; Hitomi, S.; Toyono, T.; Inenaga, K.; Dolan, J.C.; Schmidt, B.L. Cutaneous pigmentation modulates skin sensitivity via tyrosinase-dependent dopaminergic signalling. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9181.

- Mackintosh, J.A. The antimicrobial properties of melanocytes, melanosomes and melanin and the evolution of black skin. J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 211, 101–113.

- Gasque, P.; Jaffar-Bandjee, M.C. The immunology and inflammatory responses of human melanocytes in infectious diseases. J. Infect. 2015, 71, 413–421.

- Quaresma, J. Organization of the Skin Immune System and Compartmentalized Immune Responses in Infectious Diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00034-18.

- Harder, J.; Schroder, J.M.; Glaser, R. The skin surface as antimicrobial barrier: Present concepts and future outlooks. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 1–5.

- Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Ning, W.; Xu, A. Cytosolic dsDNA triggers apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in normal human melanocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 298–300.

- Iverson, M.V. Hypothesis: Vitiligo virus. Pigment Cell Res. 2000, 13, 281–282.

- Erf, G.F.; Bersi, T.K.; Wang, X.; Sreekumar, G.P.; Smyth, J.R., Jr. Herpesvirus connection in the expression of autoimmune vitiligo in Smyth line chickens. Pigment Cell Res. 2001, 14, 40–46.

- Kawamura, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Aoki, R.; Shimada, S. Innate and intrinsic antiviral immunity in skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 75, 159–166.

- Kabashima, K.; Honda, T.; Ginhoux, F.; Egawa, G. The immunological anatomy of the skin. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 19–30.

- Coates, M.; Blanchard, S.; MacLeod, A.S. Innate antimicrobial immunity in the skin: A protective barrier against bacteria, viruses, and fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007353.

- Ahn, J.H.; Park, T.J.; Jin, S.H.; Kang, H.Y. Human melanocytes express functional Toll-like receptor 4. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 17, 412–417.

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384.

- Tapia, C.; Falconer, M.; Tempio, F.; Falcón, F.; López, M.; Fuentes, M.; Alburquenque, C.; Amaro, J.; Bucarey, S.; Di Nardo, A. Melanocytes and melanin represent a first line of innate immunity against Candida albicans. Med. Mycol. 2014, 52, 445–454.

- Tam, I.; Dzierzega-Lecznar, A.; Stepien, K. Differential expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated melanocytes from lightly and darkly pigmented skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 551–560.

- Tam, I.; Stępień, K. Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by normal human melanocytes in response to lipopolysaccharide. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 507–511.

- Song, H.; Lee, S.; Choi, G.; Shin, J. Repeated ultraviolet irradiation induces the expression of Toll-like receptor 4, IL-6, and IL-10 in neonatal human melanocytes. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2018, 34, 145–151.

- Koike, S.; Yamasaki, K. Melanogenesis Connection with Innate Immunity and Toll-Like Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9769.

- Vavricka, C.J.; Christensen, B.M.; Li, J. Melanization in living organisms: A perspective of species evolution. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 830–841.

- D’Alba, L.; Shawkey, M.D. Melanosomes: Biogenesis, Properties, and Evolution of an Ancient Organelle. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1–19.

- Tolleson, W.H. Human melanocyte biology, toxicology, and pathology. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 2005, 23, 105–161.

- Montefiori, D.C.; Zhou, J. Selective antiviral activity of synthetic soluble l-tyrosine and l-dopa melanins against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Antivir. Res. 1991, 15, 11–25.

- Ali, S.M.; Yosipovitch, G. Skin pH: From basic science to basic skin care. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2013, 93, 261–267.

- Gunathilake, R.; Schurer, N.Y.; Shoo, B.A.; Celli, A.; Hachem, J.P.; Crumrine, D.; Sirimanna, G.; Feingold, K.R.; Mauro, T.M.; Elias, P.M. pH-regulated mechanisms account for pigment-type differences in epidermal barrier function. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1719–1729.

- Elias, P.M.; Menon, G.; Wetzel, B.K.; Williams, J. Barrier requirements as the evolutionary “driver” of epidermal pigmentation in humans. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2010, 22, 526–537.

- Lin, T.K.; Man, M.Q.; Abuabara, K.; Wakefield, J.S.; Sheu, H.M.; Tsai, J.C.; Lee, C.H.; Elias, P.M. By protecting against cutaneous inflammation, epidermal pigmentation provided an additional advantage for ancestral humans. Evol. Appl. 2019, 12, 1960–1970.

- Jablonski, N.G.; Chaplin, G. Colloquium paper: Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107 (Suppl. S2), 8962–8968.

- Man, M.Q.; Lin, T.K.; Santiago, J.L.; Celli, A.; Zhong, L.; Huang, Z.M.; Roelandt, T.; Hupe, M.; Sundberg, J.P.; Silva, K.A.; et al. Basis for enhanced barrier function of pigmented skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2399–2407.

- Liu, J.; Man, W.Y.; Lv, C.Z.; Song, S.P.; Shi, Y.J.; Elias, P.M.; Man, M.Q. Epidermal permeability barrier recovery is delayed in vitiligo-involved sites. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010, 23, 193–200.

- Koike, S.; Yamasaki, K.; Yamauchi, T.; Inoue, M.; Shimada-Ohmori, R.; Tsuchiyama, K.; Aiba, S. Toll-like receptors 2 and 3 enhance melanogenesis and melanosome transport in human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018, 31, 570–584.

- Sun, L.; Pan, S.; Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liang, D.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Hu, J. Toll-like receptor 9 regulates melanogenesis through NF-κB activation. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1497–1504.

- Le Poole, I.C.; van den Wijngaard, R.M.; Westerhof, W.; Verkruisen, R.P.; Dutrieux, R.P.; Dingemans, K.P.; Das, P.K. Phagocytosis by normal human melanocytes in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 205, 388–395.

- Smit, N.; Le Poole, I.; van den Wijngaard, R.; Tigges, A.; Westerhof, W.; Das, P. Expression of different immunological markers by cultured human melanocytes. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1993, 285, 356–365.

- Le Poole, I.; Mutis, T.; van den Wijngaard, R.; Westerhof, W.; Ottenhoff, T.; de Vries, R.; Das, P. A novel, antigen-presenting function of melanocytes and its possible relationship to hypopigmentary disorders. J. Immunol. 1993, 151, 7284–7292.

- Lu, Y.; Zhu, W.Y.; Tan, C.; Yu, G.H.; Gu, J.X. Melanocytes are potential immunocompetent cells: Evidence from recognition of immunological characteristics of cultured human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2002, 15, 454–460.

- Dalesio, N.M.; Barreto Ortiz, S.F.; Pluznick, J.L.; Berkowitz, D.E. Olfactory, Taste, and Photo Sensory Receptors in Non-sensory Organs: It Just Makes Sense. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1673.

- Moraes, M.N.; de Assis, L.V.M.; Provencio, I.; Castrucci, A.M.L. Opsins outside the eye and the skin: A more complex scenario than originally thought for a classical light sensor. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 385, 519–538.

- Do, M.T.H. Melanopsin and the Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells: Biophysics to Behavior. Neuron 2019, 104, 205–226.

- Lee, S.J.; Depoortere, I.; Hatt, H. Therapeutic potential of ectopic olfactory and taste receptors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 116–138.

- Cheret, J.; Bertolini, M.; Ponce, L.; Lehmann, J.; Tsai, T.; Alam, M.; Hatt, H.; Paus, R. Olfactory receptor OR2AT4 regulates human hair growth. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3624.

- Buscone, S.; Mardaryev, A.N.; Raafs, B.; Bikker, J.W.; Sticht, C.; Gretz, N.; Farjo, N.; Uzunbajakava, N.E.; Botchkareva, N.V. A new path in defining light parameters for hair growth: Discovery and modulation of photoreceptors in human hair follicle. Lasers Surg. Med. 2017, 49, 705–718.

- Mignon, C.; Botchkareva, N.V.; Uzunbajakava, N.E.; Tobin, D.J. Photobiomodulation devices for hair regrowth and wound healing: A therapy full of promise but a literature full of confusion. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 745–749.

- Castellano-Pellicena, I.; Uzunbajakava, N.E.; Mignon, C.; Raafs, B.; Botchkarev, V.A.; Thornton, M.J. Does blue light restore human epidermal barrier function via activation of Opsin during cutaneous wound healing? Lasers Surg. Med. 2019, 51, 370–382.

- Portillo, M.; Mataix, M.; Alonso-Juarranz, M.; Lorrio, S.; Villalba, M.; Rodriguez-Luna, A.; Gonzalez, S. The Aqueous Extract of Polypodium leucotomos (Fernblock((R))) Regulates Opsin 3 and Prevents Photooxidation of Melanin Precursors on Skin Cells Exposed to Blue Light Emitted from Digital Devices. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 400.

- Lan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H. Opsin 3 is a key regulator of ultraviolet A-induced photoageing in human dermal fibroblast cells. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 1228–1244.

- Lan, Y.; Zeng, W.; Dong, X.; Lu, H. Opsin 5 is a key regulator of ultraviolet radiation-induced melanogenesis in human epidermal melanocytes. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 391–404.

- Massberg, D.; Hatt, H. Human Olfactory Receptors: Novel Cellular Functions Outside of the Nose. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1739–1763.

- Suh, S.; Choi, E.H.; Atanaskova Mesinkovska, N. The expression of opsins in the human skin and its implications for photobiomodulation: A Systematic Review. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2020, 36, 329–338.

- Leung, N.Y.; Montell, C. Unconventional Roles of Opsins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 33, 241–264.

- Buhr, E.D.; Yue, W.W.; Ren, X.; Jiang, Z.; Liao, H.W.; Mei, X.; Vemaraju, S.; Nguyen, M.T.; Reed, R.R.; Lang, R.A.; et al. Neuropsin (OPN5)-mediated photoentrainment of local circadian oscillators in mammalian retina and cornea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13093–13098.

- Olinski, L.E.; Lin, E.M.; Oancea, E. Illuminating insights into opsin 3 function in the skin. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2020, 75, 100668.

- Provencio, I.; Jiang, G.; De Grip, W.J.; Hayes, W.P.; Rollag, M.D. Melanopsin: An opsin in melanophores, brain, and eye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 340–345.

- Isoldi, M.C.; Rollag, M.D.; Castrucci, A.M.; Provencio, I. Rhabdomeric phototransduction initiated by the vertebrate photopigment melanopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 1217–1221.

- Bertolesi, G.E.; McFarlane, S. Seeing the light to change colour: An evolutionary perspective on the role of melanopsin in neuroendocrine circuits regulating light-mediated skin pigmentation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018, 31, 354–373.

- Kusumoto, J.; Takeo, M.; Hashikawa, K.; Komori, T.; Tsuji, T.; Terashi, H.; Sakakibara, S. OPN4 belongs to the photosensitive system of the human skin. Genes Cells 2020, 25, 215–225.

- Miyashita, Y.; Moriya, T.; Kubota, T.; Yamada, K.; Asami, K. Expression of opsin molecule in cultured murine melanocyte. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2001, 6, 54–57.

- Denda, M.; Fuziwara, S. Visible radiation affects epidermal permeability barrier recovery: Selective effects of red and blue light. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1335–1336.

- Tsutsumi, M.; Ikeyama, K.; Denda, S.; Nakanishi, J.; Fuziwara, S.; Aoki, H.; Denda, M. Expressions of rod and cone photoreceptor-like proteins in human epidermis. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 567–570.

- Wicks, N.L.; Chan, J.W.; Najera, J.A.; Ciriello, J.M.; Oancea, E. UVA phototransduction drives early melanin synthesis in human melanocytes. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 1906–1911.

- Haltaufderhyde, K.; Ozdeslik, R.N.; Wicks, N.L.; Najera, J.A.; Oancea, E. Opsin expression in human epidermal skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 117–123.

- Hu, Q.M.; Yi, W.J.; Su, M.Y.; Jiang, S.; Xu, S.Z.; Lei, T.C. Induction of retinal-dependent calcium influx in human melanocytes by UVA or UVB radiation contributes to the stimulation of melanosome transfer. Cell Prolif. 2017, 50, e12372.

- Regazzetti, C.; Sormani, L.; Debayle, D.; Bernerd, F.; Tulic, M.K.; De Donatis, G.M.; Chignon-Sicard, B.; Rocchi, S.; Passeron, T. Melanocytes Sense Blue Light and Regulate Pigmentation through Opsin-3. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 171–178.

- Ozdeslik, R.N.; Olinski, L.E.; Trieu, M.M.; Oprian, D.D.; Oancea, E. Human nonvisual opsin 3 regulates pigmentation of epidermal melanocytes through functional interaction with melanocortin 1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11508–11517.

- Wang, Y.; Lan, Y.; Lu, H. Opsin3 Downregulation Induces Apoptosis of Human Epidermal Melanocytes via Mitochondrial Pathway. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 83–93.

- de Assis, L.V.M.; Moraes, M.N.; Magalhaes-Marques, K.K.; Castrucci, A.M.L. Melanopsin and rhodopsin mediate UVA-induced immediate pigment darkening: Unravelling the photosensitive system of the skin. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 97, 150–162.

- Jin, H.; Zou, Z.; Chang, H.; Shen, Q.; Liu, L.; Xing, D. Photobiomodulation therapy for hair regeneration: A synergetic activation of β-CATENIN in hair follicle stem cells by ROS and paracrine WNTs. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 1568–1583.

- Le Duff, F.; Fontas, E.; Guardoli, D.; Lacour, J.; Passeron, T. HeaLED: Assessment of skin healing under light-emitting diode (LED) exposure-A randomized controlled study versus placebo. Lasers Surg. Med. 2022, 54, 342–347.

- Diogo, M.; Campos, T.; Fonseca, E.; Pavani, C.; Horliana, A.; Fernandes, K.; Bussadori, S.; Fantin, F.; Leite, D.; Yamamoto, Â.; et al. Effect of Blue Light on Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6943.

- Spinella, A.; de Pinto, M.; Galluzzo, C.; Testoni, S.; Macripò, P.; Lumetti, F.; Parenti, L.; Magnani, L.; Sandri, G.; Bajocchi, G.; et al. Photobiomodulation Therapy: A New Light in the Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis Skin Ulcers. Rheumatol. Ther. 2022, 9, 891–905.

- Kemény, L.; Varga, E.; Novak, Z. Advances in phototherapy for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 1205–1214.

- Allada, R.; Bass, J. Circadian Mechanisms in Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 550–561.

- Tanioka, M.; Yamada, H.; Doi, M.; Bando, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nishigori, C.; Okamura, H. Molecular clocks in mouse skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1225–1231.

- Sandu, C.; Dumas, M.; Malan, A.; Sambakhe, D.; Marteau, C.; Nizard, C.; Schnebert, S.; Perrier, E.; Challet, E.; Pevet, P.; et al. Human skin keratinocytes, melanocytes, and fibroblasts contain distinct circadian clock machineries. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 3329–3339.

- Plikus, M.V.; Andersen, B. Skin as a window to body-clock time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12095–12097.

- Upton, B.A.; Diaz, N.M.; Gordon, S.A.; Van Gelder, R.N.; Buhr, E.D.; Lang, R.A. Evolutionary Constraint on Visual and Nonvisual Mammalian Opsins. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2021, 36, 109–126.

- Buhr, E.D.; Vemaraju, S.; Diaz, N.; Lang, R.A.; Van Gelder, R.N. Neuropsin (OPN5) Mediates Local Light-Dependent Induction of Circadian Clock Genes and Circadian Photoentrainment in Exposed Murine Skin. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 3478–3487.e4.

- de Assis, L.V.; Moraes, M.N.; da Silveira Cruz-Machado, S.; Castrucci, A.M. The effect of white light on normal and malignant murine melanocytes: A link between opsins, clock genes, and melanogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 1119–1133.

- de Assis, L.V.M.; Mendes, D.; Silva, M.M.; Kinker, G.S.; Pereira-Lima, I.; Moraes, M.N.; Menck, C.F.M.; Castrucci, A.M.L. Melanopsin mediates UVA-dependent modulation of proliferation, pigmentation, apoptosis, and molecular clock in normal and malignant melanocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118789.

- Moraes, M.N.; de Assis, L.V.M.; Magalhaes-Marques, K.K.; Poletini, M.O.; de Lima, L.; Castrucci, A.M.L. Melanopsin, a Canonical Light Receptor, Mediates Thermal Activation of Clock Genes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13977.

- Solessio, E.; Engbretson, G.A. Antagonistic chromatic mechanisms in photoreceptors of the parietal eye of lizards. Nature 1993, 364, 442–445.

- Okano, T.; Yoshizawa, T.; Fukada, Y. Pinopsin is a chicken pineal photoreceptive molecule. Nature 1994, 372, 94–97.

- Zhao, X.; Haeseleer, F.; Fariss, R.N.; Huang, J.; Baehr, W.; Milam, A.H.; Palczewski, K. Molecular cloning and localization of rhodopsin kinase in the mammalian pineal. Vis. Neurosci. 1997, 14, 225–232.

- Czeisler, C.A.; Shanahan, T.L.; Klerman, E.B.; Martens, H.; Brotman, D.J.; Emens, J.S.; Klein, T.; Rizzo, J.F., 3rd. Suppression of melatonin secretion in some blind patients by exposure to bright light. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 6–11.

- Campbell, S.S.; Murphy, P.J. Extraocular circadian phototransduction in humans. Science 1998, 279, 396–399.

- Busse, D.; Kudella, P.; Gruning, N.M.; Gisselmann, G.; Stander, S.; Luger, T.; Jacobsen, F.; Steinstrasser, L.; Paus, R.; Gkogkolou, P.; et al. A synthetic sandalwood odorant induces wound-healing processes in human keratinocytes via the olfactory receptor OR2AT4. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2823–2832.

- Pavan, B.; Dalpiaz, A. Odorants could elicit repair processes in melanized neuronal and skin cells. Neural Regen Res. 2017, 12, 1401–1404.

- Spehr, M.; Gisselmann, G.; Poplawski, A.; Riffell, J.A.; Wetzel, C.H.; Zimmer, R.K.; Hatt, H. Identification of a testicular odorant receptor mediating human sperm chemotaxis. Science 2003, 299, 2054–2058.

- Griffin, C.A.; Kafadar, K.A.; Pavlath, G.K. MOR23 promotes muscle regeneration and regulates cell adhesion and migration. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 649–661.

- Weber, L.; Al-Refae, K.; Ebbert, J.; Jagers, P.; Altmuller, J.; Becker, C.; Hahn, S.; Gisselmann, G.; Hatt, H. Activation of odorant receptor in colorectal cancer cells leads to inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172491.

- Sondersorg, A.C.; Busse, D.; Kyereme, J.; Rothermel, M.; Neufang, G.; Gisselmann, G.; Hatt, H.; Conrad, H. Chemosensory information processing between keratinocytes and trigeminal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17529–17540.

- Tsai, T.; Veitinger, S.; Peek, I.; Busse, D.; Eckardt, J.; Vladimirova, D.; Jovancevic, N.; Wojcik, S.; Gisselmann, G.; Altmuller, J.; et al. Two olfactory receptors-OR2A4/7 and OR51B5-differentially affect epidermal proliferation and differentiation. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 58–65.

- Gelis, L.; Jovancevic, N.; Veitinger, S.; Mandal, B.; Arndt, H.D.; Neuhaus, E.M.; Hatt, H. Functional Characterization of the Odorant Receptor 51E2 in Human Melanocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 17772–17786.

- Wojcik, S.; Weidinger, D.; Stander, S.; Luger, T.; Hatt, H.; Jovancevic, N. Functional characterization of the extranasal OR2A4/7 expressed in human melanocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 1216–1223.

- Adameyko, I.; Lallemend, F. Glial versus melanocyte cell fate choice: Schwann cell precursors as a cellular origin of melanocytes. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 3037–3055.

- Lerner, M.R.; Reagan, J.; Gyorgyi, T.; Roby, A. Olfaction by melanophores: What does it mean? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 261–264.

- Karlsson, J.O.; Svensson, S.P.; Martensson, L.G.; Odman, S.; Elwing, H.; Lundstrom, K.I. Effects of odorants on pigment aggregation and cAMP in fish melanophores. Pigment. Cell Res. 1994, 7, 61–64.

- Gelis, L.; Jovancevic, N.; Bechara, F.G.; Neuhaus, E.M.; Hatt, H. Functional expression of olfactory receptors in human primary melanoma and melanoma metastasis. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 569–576.

- Ranzani, M.; Iyer, V.; Ibarra-Soria, X.; Del Castillo Velasco-Herrera, M.; Garnett, M.; Logan, D.; Adams, D.J. Revisiting olfactory receptors as putative drivers of cancer. Wellcome Open Res. 2017, 2, 9.

- Suzuki, T.; Tomita, Y. Recent advances in genetic analyses of oculocutaneous albinism types 2 and 4. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008, 51, 1–9.

- Nichols, S.E., Jr.; Reams, W.M., Jr. The occurrence and morphogenesis of melanocytes in the connective tissues of the PET/MCV mouse strain. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1960, 8, 24–32.

- Mjaatvedt, C.H.; Kern, C.B.; Norris, R.A.; Fairey, S.; Cave, C.L. Normal distribution of melanocytes in the mouse heart. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell Evol. Biol. 2005, 285, 748–757.

- Brito, F.C.; Kos, L. Timeline and distribution of melanocyte precursors in the mouse heart. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2008, 21, 464–470.

- Yajima, I.; Larue, L. The location of heart melanocytes is specified and the level of pigmentation in the heart may correlate with coat color. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2008, 21, 471–476.

- Sanchez-Pina, J.; Lorenzale, M.; Fernandez, M.C.; Duran, A.C.; Sans-Coma, V.; Fernandez, B. Pigmentation of the aortic and pulmonary valves in C57BL/6J x Balb/cByJ hybrid mice of different coat colours. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2019, 48, 429–436.

- Balani, K.; Brito, F.C.; Kos, L.; Agarwal, A. Melanocyte pigmentation stiffens murine cardiac tricuspid valve leaflet. J. R. Soc. Interface 2009, 6, 1097–1102.

- Carneiro, F.; Kruithof, B.P.; Balani, K.; Agarwal, A.; Gaussin, V.; Kos, L. Relationships between melanocytes, mechanical properties and extracellular matrix composition in mouse heart valves. J. Long Term Eff. Med. Implant. 2015, 25, 17–26.

- Levin, M.D.; Lu, M.M.; Petrenko, N.B.; Hawkins, B.J.; Gupta, T.H.; Lang, D.; Buckley, P.T.; Jochems, J.; Liu, F.; Spurney, C.F.; et al. Melanocyte-like cells in the heart and pulmonary veins contribute to atrial arrhythmia triggers. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3420–3436.

- Hwang, H.; Liu, F.; Levin, M.D.; Patel, V.V. Isolating primary melanocyte-like cells from the mouse heart. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 91, 4357.

- Hwang, H.; Liu, F.; Petrenko, N.B.; Huang, J.; Schillinger, K.J.; Patel, V.V. Cardiac melanocytes influence atrial reactive oxygen species involved with electrical and structural remodeling in mice. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12559.

- Tsai, W.C.; Chan, Y.H.; Hsueh, C.H.; Everett, T.H., IV; Chang, P.C.; Choi, E.K.; Olaopa, M.A.; Lin, S.F.; Shen, C.; Kudela, M.A.; et al. Small conductance calcium-activated potassium current and the mechanism of atrial arrhythmia in mice with dysfunctional melanocyte-like cells. Heart Rhythm. 2016, 13, 1527–1535.

- Tachibana, M. Sound needs sound melanocytes to be heard. Pigment. Cell Res. 1999, 12, 344–354.

- Zhang, W.; Dai, M.; Fridberger, A.; Hassan, A.; Degagne, J.; Neng, L.; Zhang, F.; He, W.; Ren, T.; Trune, D.; et al. Perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes in the inner ear are essential for the integrity of the intrastrial fluid-blood barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10388–10393.

- Zhang, F.; Dai, M.; Neng, L.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhi, Z.; Fridberger, A.; Shi, X. Perivascular macrophage-like melanocyte responsiveness to acoustic trauma--a salient feature of strial barrier associated hearing loss. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3730–3740.

- Huang, S.; Song, J.; He, C.; Cai, X.; Yuan, K.; Mei, L.; Feng, Y. Genetic insights, disease mechanisms, and biological therapeutics for Waardenburg syndrome. Gene Ther. 2021.

- Andrade, A.; Pithon, M. Alezzandrini syndrome: Report of a sixth clinical case. Dermatology 2011, 222, 8–9.

- O’Keefe, G.A.; Rao, N.A. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2017, 62, 1–25.

- Lee, T.L.; Lin, P.H.; Chen, P.L.; Hong, J.B.; Wu, C.C. Hereditary Hearing Impairment with Cutaneous Abnormalities. Genes 2020, 12, 43.

- Anbar, T.S.; El-Badry, M.M.; McGrath, J.A.; Abdel-Azim, E.S. Most individuals with either segmental or non-segmental vitiligo display evidence of bilateral cochlear dysfunction. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 406–411.

- Ertugrul, G.; Ertugrul, S.; Soylemez, E. Investigation of hearing and outer hair cell function of the cochlea in patients with vitiligo. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13724.

- Genedy, R.; Assal, S.; Gomaa, A.; Almakkawy, B.; Elariny, A. Ocular and auditory abnormalities in patients with vitiligo: A case-control study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 1058–1066.

- Mujica-Mota, M.A.; Schermbrucker, J.; Daniel, S.J. Eye color as a risk factor for acquired sensorineural hearing loss: A review. Hear. Res. 2015, 320, 1–10.

- Wrzesniok, D.; Beberok, A.; Otreba, M.; Buszman, E. Gentamicin affects melanogenesis in normal human melanocytes. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2015, 34, 107–111.

- Wrzesniok, D.; Rok, J.; Beberok, A.; Rzepka, Z.; Respondek, M.; Pilawa, B.; Zdybel, M.; Delijewski, M.; Buszman, E. Kanamycin induces free radicals formation in melanocytes: An important factor for aminoglycosides ototoxicity. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 1165–1173.

- Murillo-Cuesta, S.; Contreras, J.; Zurita, E.; Cediel, R.; Cantero, M.; Varela-Nieto, I.; Montoliu, L. Melanin precursors prevent premature age-related and noise-induced hearing loss in albino mice. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010, 23, 72–83.

- Shibuya, H.; Watanabe, R.; Maeno, A.; Ichimura, K.; Tamura, M.; Wakana, S.; Shiroishi, T.; Ohba, K.; Takeda, K.; Tomita, H.; et al. Melanocytes contribute to the vasculature of the choroid. Genes Genet. Syst. 2018, 93, 51–58.

- Gudjohnsen, S.; Atacho, D.; Gesbert, F.; Raposo, G.; Hurbain, I.; Larue, L.; Steingrimsson, E.; Petersen, P. Meningeal Melanocytes in the Mouse: Distribution and Dependence on Mitf. Front. Neuroanat. 2015, 9, 149.

- Randhawa, M.; Huff, T.; Valencia, J.C.; Younossi, Z.; Chandhoke, V.; Hearing, V.J.; Baranova, A. Evidence for the ectopic synthesis of melanin in human adipose tissue. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 835–843.

- Page, S.; Chandhoke, V.; Baranova, A. Melanin and melanogenesis in adipose tissue: Possible mechanisms for abating oxidative stress and inflammation? Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e21–e31.

- Jehs, T.; Faber, C.; Udsen, M.S.; Jager, M.J.; Clark, S.J.; Nissen, M.H. Induction of Chemokine Secretion and Monocyte Migration by Human Choroidal Melanocytes in Response to Proinflammatory Cytokines. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 6568–6579.

- Nag, T.C. Ultrastructural changes in the melanocytes of aging human choroid. Micron 2015, 79, 16–23.

- Jang, Y.H.; Kim, S.L.; Lee, J.S.; Kwon, K.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, W.J. Possible existence of melanocytes or melanoblasts in human sebaceous glands. Ann. Dermatol. 2014, 26, 469–473.

- Vandamme, N.; Berx, G. From neural crest cells to melanocytes: Cellular plasticity during development and beyond. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1919–1934.

- Adameyko, I.; Lallemend, F.; Aquino, J.B.; Pereira, J.A.; Topilko, P.; Muller, T.; Fritz, N.; Beljajeva, A.; Mochii, M.; Liste, I.; et al. Schwann cell precursors from nerve innervation are a cellular origin of melanocytes in skin. Cell 2009, 139, 366–379.

- Tatarakis, D.; Cang, Z.; Wu, X.; Sharma, P.P.; Karikomi, M.; MacLean, A.L.; Nie, Q.; Schilling, T.F. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of zebrafish cranial neural crest reveals spatiotemporal regulation of lineage decisions during development. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 110140.

- Kaucka, M.; Szarowska, B.; Kavkova, M.; Kastriti, M.E.; Kameneva, P.; Schmidt, I.; Peskova, L.; Joven Araus, A.; Simon, A.; Kaiser, J.; et al. Nerve-associated Schwann cell precursors contribute extracutaneous melanocytes to the heart, inner ear, supraorbital locations and brain meninges. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6033–6049.

- Bonnamour, G.; Soret, R.; Pilon, N. Dhh-expressing Schwann cell precursors contribute to skin and cochlear melanocytes, but not to vestibular melanocytes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021, 34, 648–654.