1. STEC-HUS as a Zoonosis: Reservoirs, Sources, and Modes of Transmission

The importance of cattle as the primary reservoir for STEC has been hypothesized since the first outbreaks associated with undercooked hamburgers [17]. Occasionally, sheep [76] or goats [77] have been reported as sources of outbreaks. Cattle are asymptomatic carriers of STEC: after internalization in bovine epithelial cells, Shiga toxin is excluded from the endoplasmic reticulum and localizes to lysosomes, where its cytotoxicity is abrogated [78]. Reported prevalence in farm and slaughterhouse studies varies widely, but a recent meta-analysis yielded an estimated prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in North America of 10.68% (95% CI: 9.17%–12.28%) in fed beef, 4.65% (95% CI: 3.37%–6.10%) in adult beef, and 1.79% (95% CI: 1.20%–2.48%) in adult dairy. In winter months, the prevalence was nearly 50% lower than that recorded in the summer months [79], consistent with the seasonality observed in human infections [80]. Contamination by EHEC decreases during processing of the meat [81], but some authors reported that salt at concentrations used for this process may in fact enhance Stx production [82]. Among animals positive for STEC, the term “super-shedder” is applied to cattle that shed concentrations of E. coli O157:H7 ≥ 10⁴ colony-forming units/g feces. The role of ground beef as a vehicle for STEC seems to be decreasing, and recent outbreaks have been associated with raw milk products, spinach [88], municipal drinking water [89], or fenugreek [90]. In a retrospective analysis of 350 outbreaks in the USA between 1982 and 2002, Rangel and colleagues found that 52% of outbreaks were foodborne (including 21% for which ground beef was the transmission route), 14% resulted from person to person transmission, and 6% from recreational water. The transmission route remained unknown after investigation in 21% of outbreaks [91]. It is noteworthy that E. coli can survive for months in the environment, potentially leading to the contamination of fresh produce [92].

1.1. Global Burden, Spatial and Temporal Distribution of STEC-HUS Cases

Hemorrhagic colitis and STEC-HUS represent serious health issues, although the global burden remains unclear, chiefly because of the lack of diagnostic tools that are easy to use in routine and a loose surveillance network in many countries. Nonetheless, it has been estimated that STEC accounts for 2.8 million acute illnesses and 3890 HUS cases annually [

8], with a slight decrease in its incidence since 2000 [

8,

93]. The estimated cost of STEC-associated diseases could exceed US$400 million [

94,

95]. STEC-HUS is one of the most common diseases requiring emergency renal replacement therapy in children [

96] and is responsible for 2%–5% of mortality worldwide during the acute phase [

97]. In global terms, the incidence of STEC-associated diseases varies widely, mainly in relation to environmental and agricultural factors such as stockbreeding, with Argentina having the highest prevalence worldwide: 12.2 cases per 100,000 children younger than 5 years old, approximately 10-fold higher than that in other industrialized countries [

8,

98,

99]. New Zealand reports an annual infection rate of 3.3 per 100,000 persons, whereas neighboring Australia only reports 0.4 cases per 100,000 persons [

100]. Rural areas also tend to be more affected than urban ones [

101,

102], and cases occur predominantly during summer months [

99,

103]. Incidence rates of HUS vary greatly depending on the age of the patient and have peaked to 3.3 cases per 100,000 children-years in children aged 6 months to 2 years, for example in France [

80]. Contrary to common belief, most cases of STEC-HUS are sporadic [

99,

104], and the incidence of STEC-HUS has been fairly steady since its recognition in the 1980s, with only a slight decrease after 2000 [

8], despite public and industry efforts to reduce the risk of food and water contamination [

105].

1.2. Propensity to Develop STEC-HUS

Approximately 5%–10% of infected patients will develop STEC-HUS about a week after the onset of digestive signs. The propensity to develop the disease varies according to microbiological and individual characteristics, although the determinants of the disease are not fully elucidated. First, the risk of HUS is greater for O157:H7

E. coli (≈10%) and Stx2v-harboring strains than for non-O157 serotypes and Stx1-harboring strains (≈1%) [

22,

23,

41,

43,

50,

62,

63]. Since the first documented outbreaks in the 1980s, the O157:H7 strain has genetically diversified and concurrently acquired enhanced virulence due to bacteriophage-related insertions, deletions, and duplications [

106]. Second, age is also an important risk factor for HUS, with peak incidence below 5 years and above 65 years [

99,

103,

107]. Gastric acidity is an important barrier to ingested pathogens, and the use of anti-acid medications has been suggested as a risk factor [

93]. Behavioral and environmental factors such as eating undercooked meat, contact with farm animals, and consumption of raw milk or well water have been described as risk factors in case control studies [

93]. Some authors also reported that female sex [

108] and a higher socio-economic status [

109] are associated with a higher risk of developing STEC-related disease. Genetic factors, like erythrocyte and serum Gb3 level [

110,

111] or presence of the platelet glycoprotein 1b alpha 145M allele [

112], could also influence the susceptibility to HUS.

2. Pathogenesis

EHEC ranks among the most dreaded enteric pathogens in temperate countries. Following ingestion of contaminated food or water, EHEC displays a sophisticated molecular machinery consisting of a dual strategy: colonization of the bowel and Shiga toxin production. Recent progress in the understanding of HUS mechanisms has highlighted the role of the complement pathway in endothelial damage and gone a long way in deciphering the intracellular trafficking of Shiga toxin. However, most studies have focused on the O157:H7 serotype, and whether the mechanisms uncovered in the setting of O157:H7 infections apply to non-O157 strains, or whether specific mechanisms are involved, is speculative. Another shortcoming has long been the absence of a reliable animal model. Briefly, until recently, murine models did not fully recapitulate the features of STEC-HUS as a result of predominant expression of Gb3 on mouse tubular cells [

113], as opposed to glomerular endothelial cells in humans [

114,

115]. Previous mouse models also relied on the co-injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in order to boost cytotoxicity [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120], thus obscuring the significance of the results considering the uncertainty regarding the implication of LPS in this pathology in humans. Indeed, even though the LPS-binding protein has been reported to be elevated in STEC-HUS patients [

121], the role of endotoxinemia has never been properly demonstrated, as opposed to HUS resulting from Shigellosis [

122]. More recently, new models have been created with refined Stx2 injection strategies and without the need for LPS injections. These models exhibit a wider range of the pathomechanisms expected in HUS [

123]. Primate models have sometimes provided conflicting results, as exemplified in

Section 4.4 in complement pathway research.

2.1. Colonization of the Bowel: The Attaching and Effacing Phenotype

Prior to adhering to the enterocytes, EHEC must first penetrate the thick mucus layer that protects the enterocytes. It accomplishes this by secreting the StcE metalloprotease, which reduces the inner mucus layer, thus allowing EHEC to access the intestinal epithelium [

124]. Like the enteropathogenic pathovar [

20], typical EHEC harbor the LEE [

125], which includes the type 3 secretion system, a protein appendage capable of translocating a wide repertoire of effector proteins into the cytoplasm of the target cell in the distal ileum. Among these, the translocated intimin receptor (Tir), once injected into the host cell, allows for the attachment of the bacterium. Once expressed on the surface of the enterocyte it acts as the receptor for intimin (

eae) and consolidates the attachment of

E. coli to mucosal surfaces initiated by their flagella [

126] and pili [

127]. Stx plays a role in reinforcing

E. coli adherence to the epithelium by increasing the expression of nucleolin, another surface receptor for intimin [

128]. Tir also links the extracellular bacterium to the cytoskeleton of the host cell via a Tir-cytoskeleton coupling protein (Tccp, also known as EspF(U)), in the presence of a host protein insulin receptor substrate protein of 53 kDa (IRSp53) [

129], in a process termed “pedestal formation”. Tccp, in turn, activates the actin nucleation-promoting factor WASP/N-WASP, enabling

E. coli to literally seize control of the eukaryotic cytoskeletal machinery [

130,

131]. However, EHEC are not tissue invasive and, if it was not due to Shiga toxins, their pathological effect would be identical to enteropathogenic

E. coli (i.e., invasion of the colon, disruption of tight junctions, and effacement of microvilli, resulting in watery diarrhea) [

20].

2.2. Shiga Toxin Production and Effect: Gb3 Fixation and Trafficking

After bacterial lysis, Shiga toxins are released into the intestinal lumen, and its B subunit binds to its receptor globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) (see

Section 2.2). Normal enterocytes (at variance with colon cancer cells [

132]) do not express Gb3. Thus, it is believed that Stx translocates across the intestinal epithelium tight junction by binding to Gb3 expressed on Paneth cells, which are seated in the deep crypts of the small intestine [

133]. Stx does so either by paracellular transport during neutrophil (PMN) transmigration, or by Gb3-independent transcytosis and macropinocytosis [

134,

135] before being released into the bloodstream. The mechanisms governing the circulation of Stx from the intestines to the target organs are still debated (reviewed in [

136]). Some authors point to the role of polymorphonuclear leucocytes as potential carriers [

137,

138], but these results have yet to be replicated [

139,

140], and Stx possibly only binds to mature polymorphonuclear cells [

141]. In any case, the estimated half-life of Stx in serum is less than 5 min, as it rapidly diffuses to affected tissues [

142]. It is thus likely that by the time patients develop HUS, Stx has disappeared from the serum [

140,

143]. Expression of Gb3 in humans is restricted to podocytes, microvascular endothelial cells (the highest content being found on microvascular glomeruli) [

144,

145], platelets [

146], germinal center B lymphocytes [

147], erythrocytes (where it constitutes the rare P

k antigen), and neurons [

148]. The physiological role of this glycosphingolipid and the reasons behind its specific distribution in human tissues are unknown. A Gb3 knock-out mouse model resulted in no apparent phenotype, except for the loss of sensitivity to Shiga toxins [

149]. In Gb3-positive cells, the Stx-Gb3 complex induces membrane invagination [

150] that facilitates endocytosis. Importantly, this initial process of Stx endocytosis is highly dependent on the close connection of Gb3 and lipid rafts [

151] stemming from animal cell membranes. Indeed, lipid rafts contain caveolin where polymerization provides the platform on which to form early endosomes. The mobilization of microtubular units bring into play both clathrin-dependent [

150,

152] and clathrin-independent pathways [

153,

154]. Next, the Stx-Gb3 complex is addressed from early endosomes to the endoplasmic reticulum though retrograde transport, making it possible for Stx Gb3 to escape lysosomal degradation [

155]. During transport [

155], the catalytic A subunit is cleaved by the protease furin into two fragments: A1 and A2. In the endoplasmic reticulum, the disulfide bound between the two fragments is reduced [

156], and the A1 fragment translocates into the cytoplasm (anterograde transport) where it is free to exert its cytotoxic effects by removing an adenine base at the

N-glycosidic bond from the 28S rRNA of the 60S ribosome [

157], thus inhibiting protein synthesis leading to cell death [

57,

158]. The mechanism allowing Shiga toxins to bypass late endosomes and lysosomes is only partially known, but is thought to involve cycling Golgi protein GPP130, which is susceptible to degradation by physiological concentrations of manganese, yielding hope for a future therapeutic application [

159]. The pathophysiology of Shiga toxin trafficking and intracellular action is schematized in

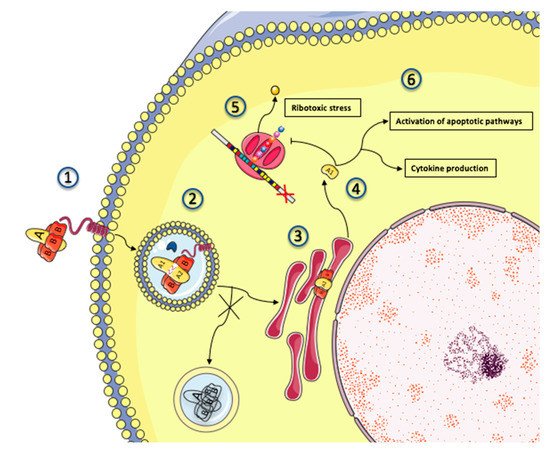

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Intracellular trafficking and cytotoxicity of Shiga toxin. A simplified depiction of Shiga toxin intracellular trafficking and mechanisms of toxicity. 1: Shiga toxins consist of a monomeric enzymatically active A subunit, non-covalently linked to a pentameric B subunit. The B subunit binds to the glycosphingolipid globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), present in lipid rafts on the surface of the target cell. 2: Shiga toxin and its receptor are internalized (endocytosis), and Shiga toxin is activated through cleavage of the A subunit into 2 fragments by the protease furin (represented by a blue crescent). Disulfide bonds keep the 2 fragments together in the endosome. 3: Shiga toxin avoids the lysosomal pathway and is directed towards the endoplasmic reticulum (retrograde transport) where the disulfide bound is reduced. 4: The A1 subunit translocates into the cytoplasm (anterograde transport) where it can exert its cytotoxic effects. 5: The processed A1 fragment cleaves one adenine residue from the 28S RNA of the 60S ribosomal subunit, thus inhibiting protein synthesis and triggering the ribotoxic and endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. 6: In addition to its ribotoxic effect, Shiga toxin activates multiple stress signaling and apoptotic pathways, and is responsible for the production of inflammatory cytokines by target cells.

2.3. Mechanisms of Shiga Toxin Cytotoxicity

Inhibition of protein translation by ribotoxic stress is the prominent mechanism of Stx cytotoxicity and a major gateway to apoptosis. The processed A1 fragment cleaves one adenine residue from the 28S RNA of the 60S ribosomal subunit, thus inhibiting protein translation and triggering the ribotoxic and endoplasmic reticulum stress responses, which in turn paves the way for cell apoptosis through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) activation [

160,

161] and various apoptotic pathways depending on the infected cell type [

162]. In addition to its ribotoxic effect, Shiga toxin activates multiple stress signaling and apoptotic pathways, and it is responsible for the production of inflammatory cytokines by target cells. On the cell surface of monocytes, Gb3 surface expression is not associated with lipid rafts, which means that Stx is routed towards the lysosomal pathway [

163,

164,

165]. This results in the production of a high amount of TNF-α, GM-CSF, and IL-8 by monocytes in response to Stx, enhancing endothelial dysfunction and organ damage in patients with HUS [

166,

167,

168,

169] along a ribotoxic-independent route [

170]. Stx can also be found in Gb3-negative intestinal cells (probably after internalization by macropinocytosis/transcytosis), where it can modulate the immune response by inhibiting the PI3K/NF-ϰB pathway [

171].

2.4. Activation of Complement Pathways: Culprit or Innocent Bystander?

By unraveling the role of alternative pathway dysregulation in atypical HUS [

172,

173,

174,

175,

176,

177], investigators have initiated the use of eculizumab, a terminal C5 inhibitor, which is now established as a mainstay in the management of patients with atypical HUS [

178,

179,

180,

181,

182]. Evidence has also been garnered suggesting the participation of an alternative pathway in STEC-HUS [

183]. Plasma levels of Bb and C5b-9, two complement pathway products [

184], and C3-bearing microparticles from platelets and monocytes [

185,

186], were found to be elevated in patients suffering from STEC-HUS. Both decreased at recovery but were not associated with disease severity. Recent in vitro studies demonstrated that Stx is capable of directly activating complement, in addition to its cytotoxic effects. Stx2 binds to complement factor H and its regulators [

187,

188]. Furthermore, Stx2 induces the expression of P-selectin on the human microvascular endothelial cell surface, which binds and activates C3 via the alternative pathway, leading to thrombi formation in a murine model of STEC-HUS [

189]. Recently, serological and genetic complement alterations were reported in 28% of STEC-HUS children [

190]. Nevertheless, these intriguing results have been diminished by the inability to replicate the findings in nonhuman primate models [

191]. The absence of C4d or C5b9 by immunochemistry in biopsies from 11 patients during the O104:H4 outbreak is also a source of concern [

192]. Lastly, mice lacking the lectin-like domain of

thrombomodulin, an endothelial glycoprotein with anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective properties, show higher glomerular C3 deposits and a higher mortality after intraperitoneal injection of Stx2 + LPS [

193], and a deficiency of this protein has been implied in rare cases of atypical HUS [

194]. Although preliminary, these results could provide the rationale for the use of ART-123, a human recombinant thrombomodulin tested in the setting of disseminated intravascular coagulation (without improvement of all-cause mortality) [

195] and acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (ongoing, NCT02739165), in STEC-HUS. Published results from three patients are encouraging [

196].

2.5. Endothelial Damage: From Stx Cytotoxicity to Thrombotic Microangiopathy

Once released into the bloodstream, Stx reach target organs [

197] and bind Gb3 on microvascular endothelial cells. Differences in Gb3 expression distribution across various vascular beds are the basis for differential organ susceptibility to Stx [

144,

198,

199]. Vascular dysfunction is both a hallmark of Shiga toxin pathophysiology and an early harbinger of negative clinical outcomes [

200,

201]. Damage to the vascular bed can broadly be categorized as (1) direct cytotoxicity to the endothelium; (2) disturbance of the hemostatic pathway; (3) enhanced release of chemokines; and (4) alternative pathway activation [

198,

201]. Shiga toxins induce a profound remodeling of the gene expression repertoire of endothelial cells rather than prompting cell death, provided that vascular cells are subjected to sublethal concentrations of Shiga toxin [

199,

202]. The net effect is that endothelial cells adopt a prothrombogenic phenotype by expressing increased levels of tissue factor (TF) [

203], releasing augmented levels of von Willebrand factor [

204,

205], and activating platelets [

206] via the CXCR4/CXCR7/SDF-1 pathway [

202]. In addition, Stx stimulates the expression of adhesion molecules [

207] and inflammatory chemokines [

208], thereby potentiating the cytotoxity of Stx [

209] and promoting the adhesion of leucocytes to endothelial cells, which in turn exacerbate thrombosis and tissue damage. At higher concentrations, Stx trigger endothelial apoptosis and cell detachment, exposing the subendothelial bed rich with prothrombogenic tissue factor and collagen [

209,

210,

211]. Finally, Stx elicits the formation of C3- and/or C9-coated microvesicles derived from platelets or red blood cells [

185,

186,

212]. Complement fraction C3a is believed to activate microvascular thrombosis by mobilizing P-selectin on the surface of endothelial cells [

189]. As a result, Stx-mediated changes in the endothelial phenotype result in a prothrombogenic environment, demonstrated by higher median plasma concentrations of prothrombin fragments, tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), and D-dimer in children in whom STEC-HUS develops, compared to those with uncomplicated infection [

200].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/toxins12020067