Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

RAP is suitable for re-construction or re-surfacing roads. RAP contains well-graded fine aggregates covered with asphalt cement and must be properly crushed and categorised. The four most frequently used processes for recycling RAP conserve natural resources and make pavement construction sustainable.

- asphalt recycling

- reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP)

- sustainable development

- rejuvenators

- flexible pavement

1. Introduction

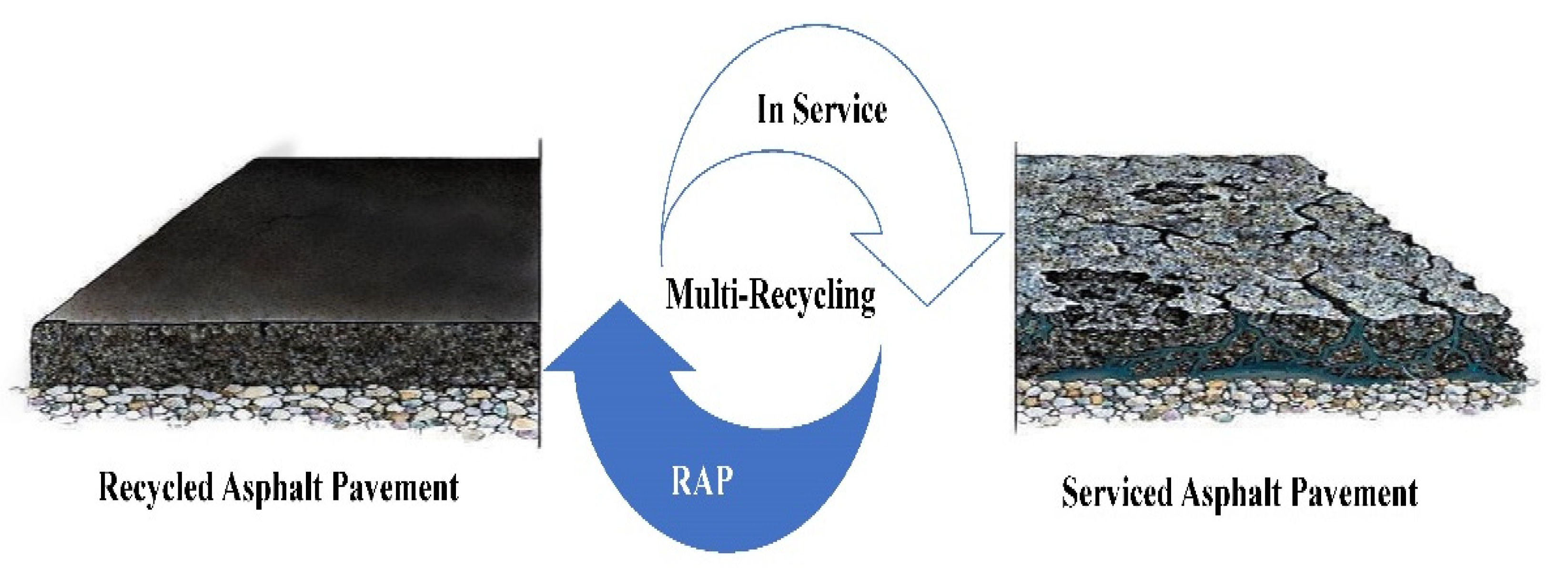

Researchers are dedicated to promoting the construction of sustainable asphalt pavements that are energy efficient and require fewer natural resources [1]. Despite the advances in RAP mixture technology and the performance and durability of waste asphalt pavement, waste recycling still poses significant challenges in Oman due to the shortage of disposal sites and the high rate of waste generation [2]. In 2021, Oman had a population of almost four million and generated about 1.6 million tonnes of solid waste, which is more than 1.5 kg per day; the amount of waste generated in Oman is among the highest globally [3]. The waste materials generated in Oman contain a high percentage of recyclables, namely 5% glass, 11% metals, 12% plastics and 26% paper [4]. Most waste materials were disposed of in authorised and unauthorised dumpsites and created health and environmental problems [5][6][7]. Recycling waste pavement materials is a sustainable alternative to road maintenance and rehabilitation [8]. Reusing RAP is an economically attractive option in Oman since some areas face a shortage of virgin aggregate and asphalt binder. Road network rehabilitation offers a valuable resource in highway construction [9][10][11]. The primary reason for using RAP is to remove the pavement materials containing asphalt and aggregates from the existing pavement. The pavement materials are recycled through a milling process that removes the upper pavement layers and replaces them with new pavement, or full-depth removal of existing pavement and reprocessing of the removed pavement [12][13]. Furthermore, the maintenance of road infrastructure produces a considerable amount of RAP that can be recycled without degrading its functionality, as shown in Figure 1. Consequently, it is essential to evaluate the multi-recycling capacity of the asphalt mixtures.

Figure 1. RAP recycling process.

RAP is suitable for re-construction or re-surfacing roads. RAP contains well-graded fine aggregates covered with asphalt cement and must be properly crushed and categorised. The four most frequently used processes for recycling RAP conserve natural resources and make pavement construction sustainable [14][15]. RAP is a suitable substitute for virgin materials because it reduces the use of virgin aggregates, thus reducing the quantity of new overpriced asphalt binder required for asphalt paving mixtures [16]. Three critical factors ensure the successful use of RAP, (i) cost-effectiveness, (ii) good performance, and (iii) environmentally friendly.

2. The Use of RAP in the Gulf Countries

Countries across the globe are exploring the use of sustainable and environmentally friendly materials, and RAP is currently a trendy new pavement material in road construction. The Gulf countries are transitioning to sustainable practices. For instance, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) uses RAP mixes in its current projects (such as the Kadra-Shawka road) without clear guidelines on cost reduction, while ensuring good pavement performance [17][18]. In 2020, Hasan et al. [19] investigated the utilisation of RAP in a segment of a 3.5 km highway. However, the study compared using RAP with Warm Mix Asphalt (WM) and Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) with recycled top-distressed asphalt pavement as natural aggregates and the environmental benefits of these alternatives for a life cycle of 30 years [20]. The study revealed that using RAP in the WMA by using about 15% of RAP content in the binder and wearing courses coupled with WMA resulted in significantly lower environmental impacts across all indicators [21].

Furthermore, at some stage in the rehabilitation, using a milled wearing course demonstrated that WMA has the capability of using high RAP content in the production mix. About 85% of in-plant WMA recycling of milled RAP was assessed and compared to virgin HMA asphalt. In Oman and the Gulf countries, RAP recycling is one of the best road maintenance options [9]. Road re-construction produces large amounts of RAP, which can be recycled into new asphalt pavement mixes. However, RAP is infrequently used in Oman because of the lack of expertise. Laboratory evaluation of cement stabilised RAP and RAP-virgin aggregate blends as base materials showed that the optimum moisture content, maximum dry density, and strength of RAP generally increase with the addition of virgin aggregate and cement, while longer curing time increases the yield strength. It is not feasible to use 100% RAP aggregate as a base material unless it is stabilised with cement [10].

In Egypt, the increasing demand for using HMA mixtures is produced merely from virgin material converted to green asphalt pavement worldwide [22]. However, recently, the existing waste RAP material, about 4 million tonnes annually, affecting landfills has led to environmental impacts by reducing energy consumption [23]. In 2015, El-Maaty & Elmohr [24] determined the mechanical properties and durability of dense-graded HMA mixtures by incorporating RAP materials. The results showed that a replacement ratio of 50% to 100% produced better durability, mechanical properties, and stripping resistance. Alwetaishi et al. [17] investigated the effects of incorporating 0%, 30%, 60% and 90% RAP and found that 90% RAP is the optimum percentage for road construction. The study similarly found that asphalt concrete mix with 90% RAP has the ideal energy efficiency; however, it is only suitable for building applications in regions with cold climates.

Compared to other recycled materials used globally, RAP is the most frequently recycled material [17]. In 2013, Sultan developed a technique to enhance the mechanical properties of RAP by mixing 40% RAP with virgin material to produce RAP with the minimum required mechanical properties for road construction. Analysis of the new mix showed that using RAP could save around 39% of the total pavement cost, hence providing Iraq with a cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and sustainable road construction technique [18]. RAP is used as a substitute for virgin aggregates throughout the globe. The UK, the USA, Japan, Canada, and other developed countries have well-established procedures, guidelines, and standards to classify and reuse recycled asphalt materials. The Gulf countries, the Middle East, and other developing countries do not have adequate standards, guidelines, and efficient procedures for determining the reclaimed asphalt materials [25][26][27][28].

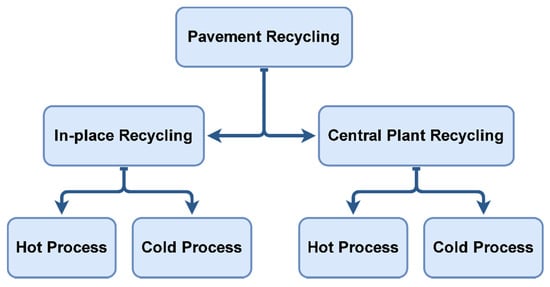

3. Classification of RAP Recycling Methods

The in situ recycling and central plant recycling methods for RAP are: cold central plant recycling (CCPR), hot in-place recycling (HIR), cold recycling, or cold in-place recycling (CIR), and full depth reclamation (FDR). In the in-situ recycling method, RAP modification is completed at the construction site, whereas in the central plant recycling method, the RAP modification is accomplished at a plant away from the construction site. Figure 2 shows the classification of RAP based on the recycling technique.

Figure 2. Classification of asphalt pavement recycling methods.

RAP recycling is classified as hot or cold recycling, depending on the use of heat. Cold recycling uses cutback or emulsion as recycling agents [29][30]. The recycling methods are also determined by the removal depth of the old pavement. Surface recycling involves removing and relaying the upper layer of the pavement, while full-depth reclamation requires removing and relaying all pavement layers, including the base [31]. Another method, hot-in-place recycling, requires heating and scarifying the pavement to the required depth, and depending on the characteristics of the milled RAP materials, this is followed by adding bitumen and new aggregates. The resulting mixture is then laid and compacted. This method reduces transportation costs, causes minor traffic disruption, and is less time consuming, but requires bulky machinery [32].

On the other hand, the CIPR approach does not require on-site heat application and uses cutback or emulsion as a binder. This method requires adequate time to cure the freshly laid layer. Additives, such as cement, quick lime or fly ash, can be used to reduce the emission of harmful gases [33][34]. Hot central plant recycling requires adding a bituminous binder and new aggregates to the RAP material in a hot mix plant away from the site. The properties and performance of the mixtures produced using this method are similar to the virgin hot mixture [34] because of the better-quality control in the central plant recycling method [30].

It is essential to store RAP material properly at construction sites that do not have sufficient storage because the RAP material is vulnerable to moisture [35][36]. Cold central plant recycling does not involve heat application at the plant and instead uses cutback or emulsion as a binder. The mixing time is critical because overmixing may prematurely break the emulsified binder. However, undermixing may cause an insufficient coating of the aggregates [29]. Table 1 summarises the research sought to determine the best RAP methods for pavement construction and rehabilitation.

Table 1. Previous research on RAP production methods.

| Researchers [Refs] | Country | Year | Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Recycling | Hot Recycling | ||||||

| CIR | CCPR | FDR | HIR | HMAR | |||

| Cross et al. [37] | The U.S.A | 2010 | √ | ||||

| Kamran et al. [38] | Pakistan | 2012 | √ | ||||

| Apeagyei et al. [39] | The U.S.A. | 2013 | √ | ||||

| Stimilli et al. [40] | Italy | 2013 | √ | ||||

| Feisthauer et al. [41] | Canada | 2013 | √ | ||||

| Hafeez et al. [42] | The U.S.A. | 2014 | √ | ||||

| Bhavsar et al. [43] | India | 2016 | √ | ||||

| Turk et al. [44] | Slovenia | 2016 | √ | ||||

| Noferini et al. [45] | Australia | 2017 | √ | ||||

| Zhao & Liu [46] | The U.S.A. | 2018 | √ | ||||

| Graziani et al. [47] | Italy | 2018 | √ | ||||

| Vázquez et al. [48] | Spain | 2018 | √ | ||||

| Bowers et al. [49] | The U.S.A. | 2019 | √ | ||||

| Gonzalo et al. [50] | Spain | 2020 | √ | ||||

| Jovanović et al. [51] | Serbia | 2021 | √ | ||||

| Iwański et al. [52] | Poland | 2022 | √ | ||||

4. RAP Standards and Mixed Design

Recently, the Oman government encouraged agencies to use RAP. The government regulations or standards for the mixing ratio, RAP analysis, and assembly/testing procedures should be established for the public and private contractors for the use of RAP [10][53]. Taha et al. [9] performed numerous tests on the feasibility of using 100/0, 80/20, 60/40, 20/80, and 0/100% RAP with virgin aggregates in road base and sub-base following the AASHTO T180 and AASHTO T193 [54]. The results showed that the maximum dry density decreased with higher RAP aggregate percentages and the California bearing ratio (CBR) increased with higher virgin aggregate contents in the blend, but the CBR decreased when using RAP as a complete replacement. Furthermore, the guideline established by the Superpave Mixtures Expert Task Group states that the design of HMA with RAP is based on a three-tier system [55][56]. Up to 15% of RAP can be utilised without changing the virgin binder grade of those chosen for the project conditions and locations. A 15 to 25% RAP content reduces the virgin binder’s low- and high-temperature by one grade, causing the ageing binder’s stiffening effect.

Lee et al. (1999) [57] examined the mechanical and rheological properties of blended asphalts containing RAP binders. However, the binders used were PG 58-28 and PG 64-22. When the amount of RAP in HMA exceeds 25%, blending charts are used to determine the suitable percentage of RAP with a given virgin binder. When using a blending chart, the RAP binder must be extracted, recovered, and tested following the specifications and guidelines presented in Table 2. Several factors determine the quantity of RAP in the new mixture, such as the specification limits for the type of mixtures; plant type; gradation; aggregate consensus properties; binder properties; the drying, heating and exhaust capacity of the plant; the moisture content of the RAP and the virgin aggregates; temperature of the virgin aggregate must be the superheated; and the ambient temperature of the RAP and virgin aggregate [58][59]. The limiting factors could be related to the material or the production process. An example of a production-related factor is the plant’s capacity to dry and heat the virgin aggregates and the RAP, where more energy is used to heat and dry the materials when the ambient temperature is low or when the material has a high moisture content. These factors influence the production rate of HMA.

Table 2. The RAP recycling formulas for development and estimation [55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63].

| Equation No. | Calculation Model | Purpose of Use |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mc=RAPw−RAPdRAPd×100 where: Mc = Moisture content expressed as a percentage RAPw = Weight of aggregate in stockpile condition RAPd = Weight of aggregate in SSD condition |

Calculate the Moisture content of RAP |

| 2 | Gse=100−Pb100Gmm−PbGb where: Gmm = Maximum specific gravity of the mixture Gb = Specific gravity of the asphalt cement Pb = Asphalt cement content as a percentage of the total mixture |

Calculate the effective specific gravity of RAP |

| 3 | Gsb=Gse(Pba×Gse 100×Gb+1) where: Gse = Effective specific aggregate gravity of aggregate Gsb = Bulk Specific Gravity of the aggregate Pba = Asphalt absorption of the aggregate Gb = Specific gravity of the asphalt cement |

Calculate the bulk specific gravity of RAP |

| 4 | %RAP=Tblend −Tvirgin TRAP −Tvirgin where: Tvirgin = Critical temperature of the virgin asphalt binder Tblend = Critical temperature of the blended asphalt binder %RAP = Percentage of RAP to be used; and TRAP = Critical temperature of the recovered RAP binder. |

Calculate the percentage of RAP |

| 5 | MdryRAP =MRAPAgg (100−Pb)×100 where: MdryRAP = Mass of dry RAP MdryAgg = Mass of RAP aggregate and binder Pb = RAP binder content |

Calculate the mass of dry RAP |

| 6 | Tc(High)=(log1−logG1a)+T1 where: Tc (high) = at which G*/sinδ is equal to 1.00 kPa G1 = G*/sinδ at temperature T1 T1 = Critical temperature a = slope of the stiffness-temperature curve |

Determine the critical high temperature |

| 7 | Tc(High)=(log2.2−logG1a)+T1 where: Tc (high) = At which G*/sinδ is equal to 2.2 kPa G1 = G*/sinδ at temperature T1 T1 = Critical temperature a = Slope of the stiffness-temperature curve |

Determine the critical high temperature based on RTFO |

| 8 | Tc(lnt)=(log5000−logG1a)+T1 where: Tc (Int) = At which G*sinδ is equal to 5000 kPa G1 = G*/sinδ at temperature T1 T1 = Critical temperature a = Slope of the stiffness-temperature curve |

Determine the critical intermediate temperature |

| 9 | Tc(S)=(log300−logS1a)+T1 where: Tc (S) = Critical low temperature S1 = S-value at temperature T1 T1 = Critical temperature |

Determine the critical low temperature |

| 10 | Tc(m)=(0.3−m1a)+T1 where: Tc (m) = Critical low temperature m1 = m-value at temperature T1 T1 = Critical temperature a = Slope of the stiffness-temperature curve |

Determine the critical low temperature |

| 11 | Tblend =Tvirgin (1−%RAP)+TRAP ×%RAP where: Tvirgin = Critical temperature of the virgin asphalt binder TRAP = Critical temperature of the blended asphalt binder %RAP = Percentage of RAP to be used TRAP = Critical temperature of the recovered RAP binder. |

Determine the critical temperature of the blended asphalt binder |

| 12 | Tvirgin =Tblend −(%RAP×TRAP )(1−%RAP) where: Tvirgin = critical temperature of the virgin asphalt binder Tblend = critical temperature of the blended asphalt binder %RAP = percentage of RAP to be used; and TRAP = critical temperature of the recovered RAP binder. |

Determine the critical temperature of the virgin asphalt binder |

| 13 | XRAP binder (s)= RAP content (%)100× RAP binder content (%) Asphalt mix binder content (%) where: XRAP binder(s) = RAP binder volume fraction Xrejuvenator = Rejuvenator oil volume fraction |

Calculate the binder content for the asphalt mix |

| 14 | D=logPENAB where: A = RAP percent binder content B = RAP percent in mixture D = Rejuvenator dosePEN = the penetration × 0.1 mm |

Calculate the rejuvenator dosage |

| 15 | E=0.5Pdt where: E = energy (lb.in/in) P = ultimate load at failure d = specimen vertical deformation at the ultimate load (in) t = specimen thickness (in) |

Calculate the absorbed energy |

| 16 | PER=Econditioned Econtrol where: PER = Percent of absorbed energy Econditioned = Average level of absorbed energy for conditioned specimens Ecotrol = Average level of absorbed energy for control specimens |

Calculate the percentage of absorbed energy |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/recycling7030035

References

- Kowalski, K.J.; Król, J.; Radziszewski, P.; Casado, R.; Blanco, V.; Pérez, D.; Viñas, V.M.; Brijsse, Y.; Frosch, M.; Le, D.M.; et al. Eco-friendly materials for a new concept of asphalt pavement. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 3582–3591.

- Zafar, S. Waste Management Outlook for the Middle East. In The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainability; Brinkmann, R., Garren, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 159–181.

- Okedu, K.E.; Barghash, H.F.; Al Nadabi, H.A. Sustainable Waste Management Strategies for Effective Energy Utilization in Oman: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 825728.

- Aljuboury, D.A.; Palaniandy, P.; Maqbali, K.S.A.A. Evaluating of performance of landfills of waste in Al-Amerat and Barka, in Oman. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 17, 1152–1160.

- Milad, A.A.; Ali, A.S.B.; Yusoff, N.I.M. A review of the utilization of recycled waste material as an alternative modifier in asphalt mixtures. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 42–60.

- Bilema, M.; Aman, M.Y.; Hassan, N.A.; Al-Saffar, Z.; Mashaan, N.S.; Memon, Z.A.; Milad, A.; Yusoff, N.I.M. Effects of Waste Frying Oil and Crumb Rubber on the Characteristics of a Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement Binder. Materials 2021, 14, 3482.

- Wahhab, H.A.A.; Ali, M.F.; Asi, I.M.; AI-Dubabe, I.A. Adaptation of Shrp Performance Based Binder Specifications to the Gulf Countries; Final Report, KACST Project AR-14-60; King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1995.

- Bilema, M.; Aman, M.Y.; Hassan, N.A.; Memon, Z.A.; Omar, H.A.; Izzi, N.; Yusoff, M.; Milad, A. Mechanical Performance of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement Modified with Waste Frying Oil and Crumb Rubber. Materials 2021, 14, 2781.

- Taha, R.; Ali, G.; Basma, A.; Al-Turk, O. Evaluation of reclaimed asphalt pavement aggregate in road bases and subbases. Transp. Res. Rec. 1999, 1652, 264–269.

- Taha, R.; Al-Rawas, A.; Al-Jabari, K.; Al-Harthy, A.; Hassan, H.; Al-Oraimi, S. An overview of waste materials recycling in the Sultante of Oman. Resour. Conserv. Recyc. 2004, 41, 293–306.

- Milad, A.; Taib, A.M.; Ahmeda, A.G.F.; Solla, M.; Yusoff, N.I.M. A review of the use of reclaimed asphalt pavement for road paving applications. J. Teknol. 2020, 82, 3.

- Arshad, A.; Karim, Z.A.; Shaffie, E.; Hashim, W.; Rahman, Z.A. Marshall properties and rutting resistance of hot mix asphalt with variable reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) content. In Materials Science and Engineering Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 271, p. 012078.

- Guthrie, W.S.; Cooley, D.; Eggett, D.L. Effects of reclaimed asphalt pavement on mechanical properties of base materials. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 2005, 44–52.

- Vandewalle, D.; Antunes, V.; Neves, J.; Freire, A.C. Assessment of Eco-Friendly Pavement Construction and Maintenance Using Multi-Recycled RAP Mixtures. Recycling 2020, 5, 17.

- Zaumanis, M.; Mallick, R.B. Review of very high-content reclaimed asphalt use in plant-produced pavement: State of the art. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2015, 16, 39–55.

- Tran, N.; Taylor, A.; Turner, P.; Holmes, C.; Porot, L. Effect of rejuvenator on performance characteristics of high RAP mixture. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2016, 18, 183–208.

- Alwetaishi, M.; Kamel, M.; Al-Bustami, N. Sustainable applications of asphalt mixes with reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) materials: Innovative and new building brick. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2019, 14, 364–374.

- Sultan, S.A.; Abduljabar, M.B.; Abbas, M.H. Improvement of the mechanical characteristics of reclaimed asphalt pavement in Iraq. Int. J. Struct. Civil Eng. Res. 2013, 2, 22–29.

- Hasan, U.; Whyte, A.; Al Jassmi, H. Life cycle assessment of roadworks in United Arab Emirates: Recycled construction waste, reclaimed asphalt pavement, warm-mix asphalt and blast furnace slag use against traditional approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120531.

- Farooq, M.A.; Mir, M.S. Use of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) in warm mix asphalt (WMA) pavements: A review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2017, 2, 10.

- Trsi, G.; Tataranni, P.; Sangiorgi, C. The Challenges of Using Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement for New Asphalt Mixtures: A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 4052.

- Mousa, E.; Azam, A.; El-Shabrawy, M.; El-Badawy, S. Laboratory characterization of reclaimed asphalt pavement for road construction in Egypt. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 44, 417–425.

- Mousa, E.; El-Badawy, S.; Azam, A. Evaluation of reclaimed asphalt pavement as base/subbase material in Egypt. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 26, 100414.

- El-Maaty, A.E.A.; Elmohr, A.I. Characterization of recycled asphalt pavement (RAP) for use in flexible pavement. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2015, 8, 233–248.

- Alam, T.B.; Abdelrahman, M.; Schram, S. Laboratory characterization of recycled asphalt pavement as a base layer. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2010, 11, 123–131.

- Hasan, A.; Hasan, U.; Whyte, A.; Al Jassmi, H. Lifecycle Analysis of Recycled Asphalt Pavements: Case Study Scenario Analyses of an Urban Highway Section. CivilEng 2022, 3, 242–262.

- Srour, I.M.; Chehab, G.R.; Gharib, N. Recycling construction materials in a developing country: Four case studies. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Econ. 2012, 3, 135–151.

- Hamdar, Y.S.; Bakchan, A.; Chehab, G.R.; Al-Qadi, I.; Little, D. Benchmarking pavement practices in data-scarce regions–case of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2021, 22, 294–306.

- Jain, S.; Singh, B. Cold mix asphalt: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124378.

- Kandhal, P.; Mallick, R. Pavement Recycling Guidelines for State and Local Governments; Federal Highway Administration FHWA-SA-98-042; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Epps, J.; Terrel, R.; Little, D.; Holmgreen, R. Guidelines for recycling asphalt pavements. J. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. 1980, 49, 144–176.

- Jones, G. Recycling of bituminous pavements on the road. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. Proc. 1979, 48, 240–251.

- Mosey, J.; Defoe, J. In-place recycling of asphalt pavements. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. Proc. 1979, 48, 261–272.

- Milad, A.; Ali, A.S.B.; Babalghaith, A.M.; Memon, Z.A.; Mashaan, N.S.; Arafa, S.; Yusoff, N.I. Utilisation of Waste-Based Geopolymer in Asphalt Pavement Modification and Construction—A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3330.

- Wolters, R. Bituminous hot mix recycling in Minnesota. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. Proc. 1979, 48, 295–327.

- Betenson, W. Recycled asphalt concrete in Utah. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. Proc. 1979, 48, 272–295.

- Cross, S.A.; Kearney, E.R.; Justus, H.G.; Chesner, W.H. Cold-in-Place Recycling in New York State; C-06-21; New York State Energy Research and Development Authority: Albany, NY, USA, 2010.

- Khan, K.M.; Kamal, M.A.; Ali, F.; Ahmed, S.; Sultan, T. Performance Comparison of Cold in Place Recycled and Conventional HMA Mixes. J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2012, 4, 27–31.

- Apeagyei, A.K.; Diefenderfer, B.K. Evaluation of Cold In-Place and Cold Central-Plant Recycling Methods Using Laboratory Testing of Field-Cored Specimens. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2013, 25, 1712–1720.

- Stimilli, A.; Ferrotti, G.; Graziani, A.; Canestrari, F. Performance evaluation of a cold-recycled mixture containing high percentage of reclaimed asphalt. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2013, 14, 149–161.

- Feisthauer, B.; Lacroix, D.; Carter, A.; Perraton, D. Simulation and Influence of Early-life Traffic Curing for Cold In-place Recycling and Full-depth Reclamation Materials. Proc. Annu. Conf.-Can. Soc. Civ. Eng. 2013, 5, 4469–4478.

- Hafeez, I.; Ozer, H.; Al-Qadi, I.L. Performance characterization of hot in-place recycled asphalt mixtures. J. Transp. Eng. 2014, 140, 04014029.

- Bhavsar, H.; Dubey, R.; Kelkar, V. Rehabilitation by in-situ cold recycling technique using reclaimed asphalt pavement material and foam bitumen at vadodara halol road project (SH87)—A case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 17, 359–368.

- Turk, J.; Pranjić, A.M.; Mladenovič, A.; Cotič, Z.; Jurjavčič, P. Environmental comparison of two alternative road pavement rehabilitation techniques: Cold-in-place-recycling versus traditional re-construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 45–55.

- Noferini, L.; Simone, A.; Sangiorgi, C.; Mazzotta, F. Investigation on performances of asphalt mixtures made with Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement: Effects of interaction between virgin and RAP bitumen. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2017, 10, 322–332.

- Zhao, S.; Liu, J. Using recycled asphalt pavement in construction of transportation infrastructure: Alaska experience. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 155–168.

- Graziani, A.; Iafelice, C.; Raschia, S.; Perraton, D.; Carter, A. A procedure for characterizing the curing process of cold recycled bitumen emulsion mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 754–762.

- Vázquez, V.F.; Terán, F.; Huertas, P.; Paje, S.E. Field assessment of a Cold-In place-recycled pavement: Influence on rolling noise. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 154–162.

- Bowers, B.F.; Diefenderfer, B.K.; Wollenhaupt, G.; Stanton, B.; Boz, I. Laboratory properties of a rejuvenated cold recycled mixture produced in a conventional asphalt plant. In Airfield and Highway Pavements 2019: Testing and Characterization of Pavement Materials; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 100–108.

- Gonzalo-Orden, H.; Linares-Unamunzaga, A.; Pérez-Acebo, H.; Díaz-Minguela, J. Advances in the Study of the Behavior of Full-Depth Reclamation (FDR) with Cement. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3055.

- Matić, B.; Jovanović, S.; Marinković, M.; Sremac, S.; Kumar Das, D.; Stević, Ž. A Novel Integrated Interval Rough MCDM Model for Ranking and Selection of Asphalt Production Plants. Mathematics 2021, 9, 269.

- Iwański, M.; Mazurek, G.; Buczyński, P.; Iwański, M.M. Effects of hydraulic binder composition on the rheological characteristics of recycled mixtures with foamed bitumen for full depth reclamation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 330, 127274.

- Bilema, M.; Aman, Y.B.; Hassan, N.A.; Al-Saffar, Z.; Ahmad, K.; Rogo, K. Performance of Aged Asphalt Binder Treated with Various Types of Rejuvenators. Civ. Eng. J. 2021, 7, 502–517.

- Officials, Transportation. AASHTO Guide for Design of Pavement Structures; The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 1993.

- Bukowski, J.R. Guidelines for the Design of Superpave Mixtures Containing Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP). In Proceedings of the Memorandum, ETG Meeting, FHWA Superpave Mixtures Expert Task Group, San Antonio, TX, USA, 28 March 1997.

- Al-Qadi, I.L.; Carpenter, S.H.; Roberts, G.; Ozer, H.; Aurangzeb, Q.; Elseifi, M.; Trepanier, J. Determination of Usable Residual Asphalt Binder in RAP; Illinois Center for Transportation (ICT): Rantoul, IL, USA, 2009.

- Lee, K.W.; Soupharath, N.; Shukla, A.; Franco, C.A.; Manning, F.J. Rheological and mechanical properties of blended asphalts containing recycled asphalt pavement binders. J. Assoc. Asph. Paving Technol. 1999, 68, 89.

- National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP). Recommended Use of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement in the Superpave Mix Design Method: Guidelines; Research Results Digest 253; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Olita, S.; Ciampa, D. SuPerPave® Mix Design Method of Recycled Asphalt Concrete Applied in the European Standards Context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9079.

- Terrel, R.; Joseph, P.; Fritchen, D. Five-year experience on low-temperature performance of recycled hot mix. Transp. Res. Rec. 1992, 2, 56–65.

- Al-Qadi, I.L.; Elseifi, M.; Carpenter, S.H. Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement—A Literature Review. Illinois 2007. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2142/46007 (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Huang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Kingery, W.; Zuo, G. Fatigue crack characteristics of HMA mixtures containing RAP. In Proceedings of the Fifth International RILEM Conference on Reflective Cracking in Pavements, Limoges, France, 5–7 May 2004; RILEM Publications SARL: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 631–638.

- Kandahl, P.S.; Rao, S.S.; Watson, D.E.; Young, B. Performance of Recycled Hot Mix Asphalt Mixtures, NCA Technology Report, 95-01; 1995. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/13635 (accessed on 16 April 2022).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!