Whether DOAC can be used instead of VKA in patients undergoing TAVR and requiring OAC is a matter of debate. The use of DOACs has been widely approved in patients with nonvalvular AF, with proven noninferiority versus VKA in the prevention of thromboembolic events for dabigatran, rivaroxaban and edoxaban [

151,

152,

153], and superiority for apixaban, with lower rate of bleeding events [

154]. In comparison with warfarin, DOACs reduce the risk of stroke, systemic embolism and intracranial hemorrhage in AF patients with valvular heart disease (VHD) (with the exception of severe mitral stenosis or mechanical heart valve) [

155]. Furthermore, the North American Consensus Statements have recently been updated and DOAC is the treatment of choice in AF patients undergoing PCI [

156].

AF is frequent in TAVR patients and associated with poorer outcomes. Furthermore, OAC is a correlated to mortality independently of AF in this population [

113]. Observational studies comparing DOACs with VKA provided inconsistent findings [

157,

158,

159,

160]. In the combined France-TAVI and France-2 registries, 8962 patients were treated with OAC after TAVR (24% on DAOCs, 77% on VKAs). After 3 years of follow-up, after propensity matching, there was a significant increase of 37% in mortality rates (VKA vs. DOAC: 35.6% vs. 31.2%;

p < 0.005) and 64% in major bleeding (12.3% vs. 8.4%;

p < 0.005) with VKAs compared to DOACs. No between-group difference on ischemic stroke and acute coronary syndrome was reported [

161]. Consistently, the STS/ACC registry, the largest to date with 21,131 patients undergoing TAVR with pre-existing or incident AF discharged on OAC, demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of death in patients on DOACs versus VKAs (15.8% vs. 18.2%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.85–1.00;

p = 0.043). In addition, DOACs were also associated with a 19% decrease in bleeding rates compared to VKAs (11.9% vs. 15.0%, respectively; adjusted HR 0.81; 95% CI, 0.33–0.87;

p < 0.001). The 1-year incidence of ischemic stroke was similar between the two groups [

162]. Moreover, in a recent meta-analysis of 12 studies, including patients with an indication for OAC, DOACs were associated with lower all-cause mortality compared to VKAs after more than 1 year of follow-up (RR = 0.64; 95% CI 0.42–0.96;

p = 0.03), while no between-group difference was shown in stroke and valve thrombosis rates [

163]. Conversely, in one nonrandomized study, the composite outcome of any cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality was 44% higher in the DOAC group vs. VKA (21.2% vs. 15.0%, respectively; HR 1.44;

p = 0.05). Nevertheless, the 1-year incidence of all-cause mortality was comparable between the two groups (16.5% vs. 12.2% for DOAC and VKA, respectively; HR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.90–2.06;

p= 0.136). Bleeding rates were also similar between the two groups [

164]. Of note, the increase of ischemic events was of borderline statistical significance. These findings could be the result of heterogeneity in baseline and procedural characteristics, considering the absence of randomization, and the higher prevalence or renal impairment and peripheral vascular among patients treated with NOAC. Furthermore, previously described observational studies and large registries did not correlate with these findings. Thus, in observational and large registries, DOACs seems to provide similar efficacy to VKA in the prevention of stroke, but improvement in the rates of mortality and bleeding, which could favor the use of DOACs after TAVR in patients with an underlying indication of OAC. However, these data from non-randomized studies should be carefully interpreted.

5.5. Patients without Underlying Indication for Anticoagulation

Considering the high risk of thromboembolic complications following TAVR and the potential development of subclinical obstructive valve thrombosis, post-TAVR OAC has been tested in the absence of other indications for anticoagulation. The GALILEO trial compared 3 months administration of low dose rivaroxaban (10 mg daily) plus aspirin followed by rivaroxaban alone with 3 months of aspirin plus clopidogrel followed by aspirin alone. The trial was terminated prematurely, with treatment with rivaroxaban being associated with a significantly higher risk of all-cause death (increase of 69%), of thromboembolic complications and of VARC-2 major, disabling or life-threatening bleeding (increase of 50%), compared to antiplatelet therapy [

150]. Consistently, in the Stratum 2 of the ATLANTIS trial, treatment with apixaban resulted in higher all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality compared with SAPT or DAPT among patients without an indication of OAC [

115]. Similar results were reported in An et al. meta-analysis [

162]. In the ESC/EACTS guidelines, OAC is contraindicated after TAVR in patients with no indications of OAC (class of recommendation: III, level of evidence: B) [

2].

5.6. Ongoing Trials Evaluating Antithrombotic Therapy after TAVR

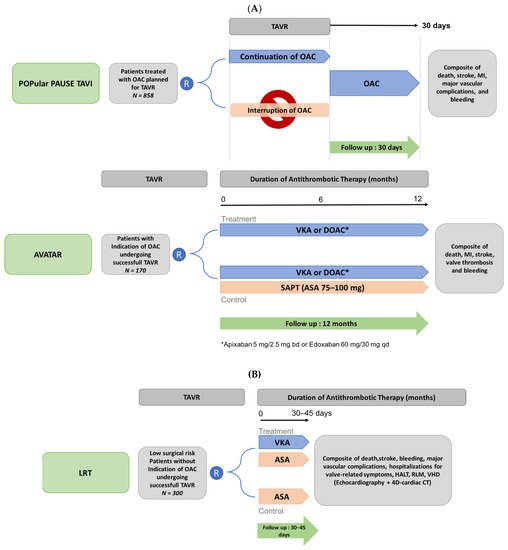

The main ongoing trials evaluating the antithrombotic regimen in TAVR patients are summarized in Figure 7. The AVATAR (Anticoagulation Alone Versus Anticoagulation and Aspirin Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Interventions) open-label randomized controlled trial (n = 170) will evaluate the safety and efficacy of anticoagulant therapy alone (VKA or DOAC) versus anticoagulant plus aspirin (NCT02735902) in patients requiring OAC who underwent successful TAVR, after a 12-month follow-up. This trial is expected to end in April 2023. The POPular PAUSE TAVI randomized trial previously cited will provide information on the optimal anticoagulant strategy to adopt during the TAVR procedure, with a comparison of the effect of peri-operative discontinuation versus continuation of OAC on VARC-2 ischemic and bleeding outcomes in patients undergoing TAVR with prior OAC therapy (NCT04437303). Finally, in low-risk patients undergoing TAVR with no indication for OAC, the ongoing LRT (Strategies to Prevent Transcatheter Heart Valve Dysfunction in Low Risk Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement) trial is currently exploring the effect of VKA in addition to aspirin, compared to aspirin only, on clinical outcomes and valvular heart deterioration (NCT03557242, with the estimation completion date in July 2023).

Figure 7. Design of ongoing trials of antithrombotic strategies in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement with (A) and without (B) an indication for oral anticoagulation. 4D-CT: 4-dimensional computed tomography; ASA: aspirin; DOAC: direct oral anticoagulation; HALT: hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; MI: myocardial infarction; RLM: reduced leaflet motion; TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement; VHD: valvular hemodynamic deterioration; VKA: Vitamin K antagonist; bd: bi-day; qd: quotidianly. (A) Patients with an underlying indication for OAC. (B). Patients without having an indication for OAC.