Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Late-stage Parkinson’s disease (LSPD) patients are highly dependent on activities of daily living and require significant medical needs. In LSPD, there is a significant caregiver burden and greater health economic impact compared to earlier PD stages.

- Parkinson’s disease

- late stage

- cognitive impairment

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) evolves throughout different stages, from the early one since the moment of diagnosis to the advanced stage when motor complications appear and become troublesome, up to the late stage (LS), which is the final part of the disease. LSPD has been labeled an “orphan population” due to the little data available on its care needs and the reduced number of available therapeutic options, largely due to the paucity or absence of clinical studies focused on these patients [1][2]. The above-described therapeutic landscape is in sharp contrast with LSPD being the patient group with the greatest impairment and level of dependence, having more complex care needs, and the highest health and economic impact among the different stages of PD stages [3]. In addition, LSPD is undoubtedly expected to have an exponential increase in its prevalence in the next few decades [4].

2. Therapeutic Challenges: Oral and Non-Pharmacological Approaches

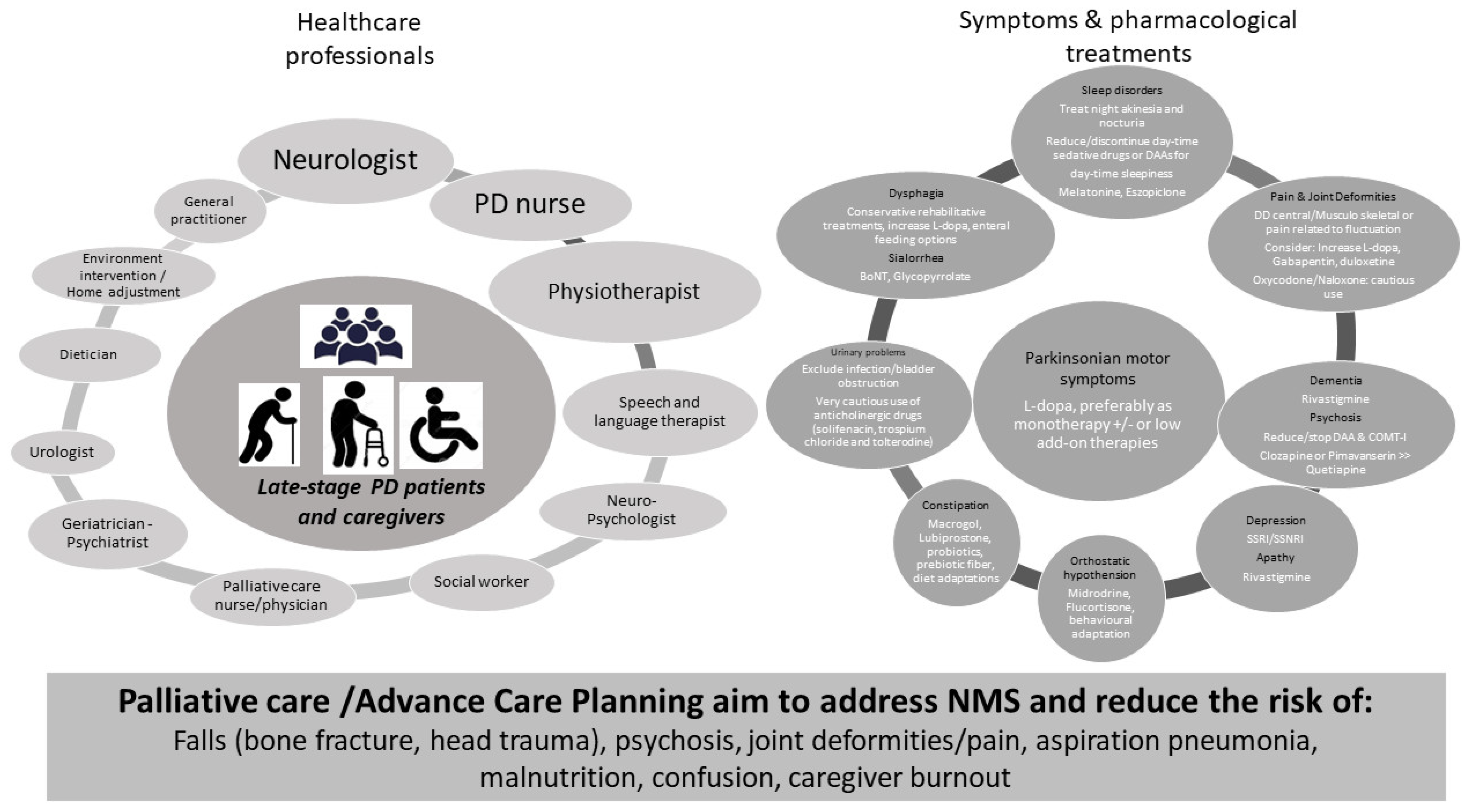

The reduction of the risk associated with the above-mentioned disease milestones has a crucial role in the management of LSPD (Figure 1), together with a symptom-based treatment.

Figure 1. Pillars for Late-stage PD treatment. Left panel: health care professionals involved in LSPD management. Right panel: motor and NMS and available pharmacological options. Bottom: the main objectives of prevention strategies for LSPD patients. COMT−I: Catechol−O-methyl transferase inhibitors; DAAs: dopamine-agonist; SSRI/SNRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor/serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Regarding symptomatic treatment, a good practice point consists in using L-dopa, preferentially as monotherapy and at the lowest dose possible. Indeed, other (add-on) dopaminergic therapies, including dopamine-agonists, catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors, are more likely to induce hallucinations, confusion, or orthostatic hypotension (OH) among elderly and frail PD patients and, consequently, should be cautiously used in this disease stage [5]. L-dopa has been shown to be effective on rigidity and tremor, especially among non-demented, tremor-dominant patients or those with dyskinesia in LSPD [6][7][8]. These patients may also benefit from cautious L-dopa dose increments for appendicular Parkinsonian symptoms. Conversely, the effect of L-dopa is often modest or barely absent on axial features, which include speech impairment, postural instability, and FoG. Consequently, a disproportionate increment of L-dopa dose to target these features may be unsuccessful and induce significant adverse effects (AEs), namely, worsening confusion or OH.

The management of NMS is based on the application of the clinical evidence available for earlier PD stages [9] and herein summarized in Figure 1 (right panel) [5][10] (see also BOX). Nevertheless, the dose therapeutic response, tolerance, and AEs profile may be distinct in LSPD, limiting its applicability. Of note, the regular assessment by a movement disorder specialist, offering specific treatment recommendations, has been shown to have a positive effect on the quality of life (QoL) of LPSD patients, in comparison with the follow-up exclusively by other physicians such as a general practitioner or general neurologist [11].

The implementation of non-pharmacological approaches is an important component in the management of LSPD. Non-pharmacological approaches include physiotherapy for the reduction of risk of falls and joint deformities, speech and language therapy (SLT) for the prevention of aspiration pneumonia, and cognitive training. When considering the complex care needs of PD patients, a multispecialty approach has been suggested as the most suitable solution for tailored and comprehensive care delivery to address care complexity in PD throughout the disease course. Nevertheless, the feasibility of these approaches is yet to be formally evaluated in LSPD, which needs to consider the presence of cognitive impairment and barriers to mobility that lead to an intervention being delivered at home and not in the clinic. A multidisciplinary team ideally involves a wide range of medical specialties and other health care professionals (Figure 1, left panel), implying the development of collaboration strategies amongst team members. There are different levels of care organization which can be coined as multidisciplinary (each discipline is responsible for a specific patient need without standardized coordination), interdisciplinary (a collaboration of the healthcare team members that make group decisions), or integrated care (a care plan involving multiple members of a health care team that is guided by consensus building and engagement of patients as team members). The ideal approach for LSPD patients is that the various components of a care team described above form an integrated palliative care approach to achieve an optimized and effective care delivery (see paragraph on “Home care”).

3. Management of Device-Aided Therapies in LSPD

LSPD patients previously submitted to device-aided therapies (DAT), i.e., deep brain stimulation (DBS), levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG), or continuous apomorphine subcutaneous infusion (CSAI), represent a small subset of patients in LSPD but are expected to require a more specialized level of care [12][13].

One caveat amongst DATs is CSAI. There is no report of LSPD patients with ongoing CSAI treatment, as likely AEs such as hallucinations, confusion, and OH determine its earlier discontinuation before a patient reaches LSPD. In addition, there are no data about the rate of drop-outs for LSPD in long-term studies of CSAI. Thus, the consideration of this treatment for LSPD patients relies solely on an expert opinion level of evidence. If CSAI is maintained in LSPD, the lowest effective dose should be used (as with any other dopaminergic intervention), likely ranging from 1–3 mg/h over the day, with careful monitorization of AEs, even if no formal recommendation/guideline is available. Equally, de novo administration of CSAI should be carefully considered, namely, the risk for poor tolerance (including worsening confusion) to dopamine agonist treatment in LSPD.

Regarding DBS, a common clinical question is the maintenance of this therapy at the time of replacement of the implantable pulse generator in patients no longer having clinically significant motor complications, and for whom the benefit of DBS may be doubtful. A small randomized, double-blind trial attempted to address this question, finding that DBS has a short and long-term benefit, similar to L-dopa, even in LSPD [14]. Worsening of dysphagia and Parkinsonism may occur after switching-off DBS and, at times, after a few days. An algorithm to evaluate the therapeutic benefit of DBS and criteria to discontinue DBS has been proposed [14]. A rule of thumb is to consider increasing neurostimulation with particular caution, especially for the most troublesome axial symptoms, as these likely are a manifestation of disease progression and will not be responsive to dopaminergic treatment [15] and thus to neurostimulation increment.

Regarding LCIG, there is no study has specifically focused on LSPD. A case-control study has recently shown that elderly PD patients (>80 years old) matched for disease duration and LCIG treatment duration with younger PD patients (<75 years) may have a similar benefit in QoL without a higher occurrence of treatment-related AEs [16]. Researchers suggests the use of LCIG in elderly patients who still present motor complications and are deemed poor candidates for DBS (see the case in the box). Nevertheless, the indication for LCIG (presence of troublesome motor complications, absence of dementia, presence of a caregiver) remains the same and needs to be carefully scrutinized in LSPD. Of note, PEG-J used for LCIG treatment is a viable route for enteral nutrition in LSPD patients with severe dysphagia [17].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jpm12050813

References

- Coelho, M.; Ferreira, J.J. Late-stage Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 435–442.

- Schrag, A.; Hommel, A.; Lorenzl, S.; Meissner, W.G.; Odin, P.; Coelho, M.; Bloem, B.R.; Dodel, R.; Clasp, C. The late stage of Parkinson’s-results of a large multina-tional study on motor and non-motor complications. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2020, 75, 91–96.

- Kruse, C.; Kretschmer, S.; Lipinski, A.; Verheyen, M.; Mengel, D.; Balzer-Geldsetzer, M.; Lorenzl, S.; Richinger, C.; Schmotz, C.; Tönges, L.; et al. Resource Utilization of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease in the Late Stages of the Disease in Germany: Data from the CLaSP Study. PharmacoEconomics 2021, 39, 601–615.

- Dorsey, E.R.; Bloem, B.R. The Parkinson Pandemic—A Call to Action. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 9–10.

- Fabbri, M.; Kauppila, L.A.; Ferreira, J.J.; Rascol, O. Challenges and Perspectives in the Management of Late-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, S75–S83.

- Fabbri, M.; Coelho, M.; Abreu, D.; Ferreira, J.J. Levodopa response in later stages of Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2019, 77, 160–162.

- Fabbri, M.; Coelho, M.; Abreu, D.; Guedes, L.C.; Rosa, M.M.; Costa, N.; Antonini, A.; Ferreira, J.J. Do patients with late-stage Parkinson’s disease still respond to levodopa? Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016, 26, 10–16.

- Rosqvist, K.; Horne, M.; Hagell, P.; Iwarsson, S.; Nilsson, M.H.; Odin, P. Levodopa Effect and Motor Function in Late Stage Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, 59–70.

- Seppi, K.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Coelho, M.; Fox, S.H.; Katzenschlager, R.; Perez Lloret, S.; Weintraub, D.; Sampaio, C. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease-an evidence-based medicine review. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Dis-Order Soc. 2019, 34, 180–198.

- Rukavina, K.; Batzu, L.; Boogers, A.; Abundes-Corona, A.; Bruno, V.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Non-motor complications in late stage Parkinson’s disease: Recognition, management and unmet needs. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2021, 21, 335–352.

- Hommel, A.L.; Meinders, M.J.; Weerkamp, N.J.; Richinger, C.; Schmotz, C.; Lorenzl, S.; Dodel, R.; Coelho, M.; Ferreira, J.J.; Tison, F.; et al. Optimizing Treatment in Undertreated Late-Stage Parkinsonism: A Pragmatic Randomized Trial. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, 1171–1184.

- Modugno, N.; Antonini, A.; Tessitore, A.; Marano, P.; Pontieri, F.E.; Tambasco, N.; Canesi, M.; Fabbrini, G.; Sensi, M.; Quatrale, R.; et al. Impact of Supporting People with Advanced Parkinson’s Disease on Carer’s Quality of Life and Burden. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2899–2912.

- Leta, V.; Dafsari, H.; Sauerbier, A.; Metta, V.; Titova, N.; Timmermann, L.; Ashkan, K.; Samuel, M.; Pekkonen, E.; Odin, P.; et al. Personalised Advanced Therapies in Parkinson’s Disease: The Role of Non-Motor Symptoms Profile. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 773.

- Fabbri, M.; Zibetti, M.; Rizzone, M.G.; Giannini, G.; Borellini, L.; Stefani, A.; Bove, F.; Bruno, A.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Modugno, N.; et al. Should We Consider Deep Brain Stimulation Discontin-uation in Late-Stage Parkinson’s Disease? Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2020, 35, 1379–1387.

- Limousin, P.; Foltynie, T. Long-term outcomes of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 234–242.

- Morgante, F.; Oppo, V.; Fabbri, M.; Olivola, E.; Sorbera, C.; De Micco, R.; Ielo, G.C.; Colucci, F.; Bonvegna, S.; Novelli, A.; et al. Levodopa–carbidopa intrajejunal infusion in Parkinson’s disease: Untangling the role of age. J. Neurol. 2020, 268, 1728–1737.

- Bove, F.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Naranian, T.; Fasano, A. Enteral feeding in Parkinson’s patients receiving levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2017, 42, 109–111.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!