Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Many factors influence the quality of virgin olive oil: olives, harvesting methods, extraction technologies from the crushing of the olives to the separation of the oily phase. All the operations required in the oil extraction process are aimed at obtaining the highest quality of oil from the fruits. In this context, the preparation phase of the olive paste is very fundamental.

- quality

- fruit

- extra virgin olive oil

1. Introduction

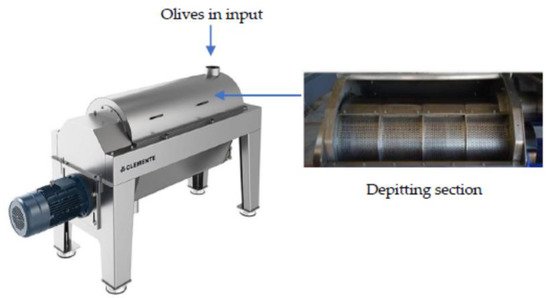

Many factors influence the quality of virgin olive oil: olives, harvesting methods, extraction technologies from the crushing of the olives to the separation of the oily phase [1][2]. All the operations required in the oil extraction process are aimed at obtaining the highest quality of oil from the fruits. In this context, the preparation phase of the olive paste is very fundamental [3]. Over time, traditional pressure extraction has been replaced with the centrifugation system; this system has some disadvantages, due to the addition of hot water to the olive paste. Therefore, a two-phase centrifugal decanter has been manufactured which can separate oil from pasta without adding water [4]. Extra virgin olive oil of high-quality presents both very special sensory characteristics and health benefits, therefore there is an increased consumers demand for this product. The goal of increasing the quality standards for virgin olive oil has stimulated the research for new technologies. Twenty years have passed since various producers have developed technological procedures that include removing the stone before the olive oil extraction process [5][6][7][8][9][10][11]. In the production plants of extra virgin olive oil from pitted olives, the pit removal machines are placed at the beginning of the olive processing line [12]. The washed olives are placed in continuous pitting machines which can be of two types [13][14]: total pitting machines (which eliminate all the stones) and partial pitting machines (which eliminate part of the stones). Total pitting machines had a limited diffusion because, despite adjustments of the decanter, the extraction yield is always slightly lower than that obtained using a paste containing a network of stone fragments. However, this problem is now reduced by controlling the water content of the pitted pulp, to ensure optimal separation of the oil [15][16]. The pitting takes place owing to the action of a rotating shaft (700–800 rpm) connected to metal bars coated in rubber, placed inside a horizontal perforated cylinder (holes from 4 to 6 mm) in turn placed inside a cylindrical casing with a continuous wall with, underneath, a tank for pulp collection (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Destoning machine (photos courtesy of Clemente Industry, Olive oil Srl, Italy)

The olives enter the machine by means of an auger. The pulp comes out through the holes in the internal cylinder and falls into the collection tank, while the rotating shaft pushes the stones outwards, on the side opposite the feeder. The hourly capacity of the machine is about 2000 kg/h of olives and the pulp does not undergo significant temperature increases [13]. The partial pitting machines (Figure 2) consist of two sections [16][17]: In the first, normal milling takes place through two counter-rotating toothed rollers at different angular speeds (about 70 rpm and about 140 rpm); the second section is very similar to a total pitting machine, with the difference that the holes in the internal cylinder have smaller diameters (2.5–3.5 mm). In this way, some stone fragments remain in the paste (generally 50–70%). The hourly capacity of these machines varies between 2000 and 6000 kg/h of olives [13]. With particular varieties of olives or with olives in the most advanced state of ripeness, pitting can cause some problems: in fact, stone dust can be generated which can clog the decanter, reducing the oil extraction yield [18]. The main advantage of using the destoned paste is that it ameliorates the sensory properties and prolongs the shelf-life of extra virgin olive oil. In the destoning process, the enzymes which were contained in the seeds are turned away so that they do not catalyze the oxidative reactions of chemical compounds [19][20][21].

Figure 2. Partial destoner machine proposed by Romaniello, Leone and Tamborrino [16]. Legend: A: chassis; B: mechanical crusher; C: destoner; D: cochlea for pits extraction; E: malaxing; F: olive feeding.

Moreover, thermal activities, responsible for the decomposition of different constituents present in oils, had a decrease [22]. In some research [23][24], it was observed that the destoning technique noticeably affected the phenolic compounds, in fact the destoned fruit oils were characterized by higher phenols content. These findings showed that owing to the peroxidase (POD) activity observed, the seed influences the phenols oxidative reactions, above all in the extractive phase [25]. Ranalli et al. [26] investigated the oils from destoned olives compared with non-stoned olives. Stone removal allowed the production of highly nutraceutical oils, rich in biophenols. Results reported in the literature [3] showed that the oil of destoned fruits had inferior values of free acidity and the spectrophotometric indices (K232 and K270, which show UV absorption in 232 nm and 270 nm) than the oil obtained by traditional methods, therefore, they had less oxidation. Both the phenolic fraction and the volatile compounds increase in olive oils obtained from destoned olives, leading to an improvement in the nutritional and sensory characteristics of the product. It was observed that stone removal increased in the oils the volatile compounds bonded to the “green” probably because the enzymes involved in the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway led to different products depending on whether they are found in the pulp or in the seed [11]. Titouh, Mazari and Meziane [27] reported the effect of both destoning of olives and the addition of talc as co-adjuvant, used in modern oil mills, during malaxation of the paste on the yield of extracted oil. As expected, destoning carried out a slight decrease of about 1.1 percent point of the oil yield compared to the whole fruits. It was observed that the addition of talc at 2.5% does not significantly improve the oil extraction from destoned fruits; however, the destoning of olives allowed improvement of oil quality, valuing local the traditional olive-growing by giving them bonding to the territory. In this sense, the authors noted in fact an enhancement in qualitative traits of oil which could add value to the local products distinguishing in comparison to those obtained by standard methods. In another study conducted by Guermazi, Gharsallaoui, Perri, Gabsi and Benincasa [28], the life cycle analysis was evaluated in a new olive oil technology process, consisting of a destoning and a two-phase extraction system. They obtained both the pulp to produce quality extra virgin olive oil and the stones to produce energy, thus concurring to reducing the environmental impact. Romaniello, Leone, and Tamborrino [16] designed and built an industrial prototype of a partial destoner machine. This machine did not completely remove the stone, but only a quantity of about 50% of the olive stone fragments. The authors investigated the extraction efficiency of the implant, the quality of the olive oil, and the rheological aspects. The results pointed out that the partial destoner machine compared to the total destoning allowed an increase in the extraction yield, a significant reduction in the viscosity of the paste, and the stones can be recovered. Moreover, the oils from the partial destoner machine were distinguished by the intensity of fruity flavor and aroma in comparison to samples from whole olives. A recent work, particularly interesting [17], introduced a new partial destoning machine (called Moliden), which had been placed in an experimental trial to assess the impact on the quality and sustainability of the extraction process. The partial de-stoner machine proposed by the authors allows considerable savings in the production process since it includes two sections: crushing and destoning. This aspect is especially important since compared with the standard parameter of the high-quality wood pellet it provides a higher quality stone to be used as a biomass fuel. This could have a significant impact on the environmental sustainability of the process. The destoning treatment also played an important role in the improvement of the aldehydes and esters with a positive impact on extra virgin olive oil flavor. Moreover, the authors found an increase in bioactive compound content that enhanced bitter and pungent sensory notes. Yorulmaz, Tekin and Turan [29] evaluated the influence of stone removal and malaxation in the nitrogen atmosphere on the oxidative stability of the oils. The findings highlighted that the combined effect of malaxing under nitrogen and destoning made it possible to obtain high-quality oils. Although the employment of the destoner can ameliorate the working capacity of the mill plant, as it eliminates part of the solid waste before extraction, a third-generation decanter is needed to separate the oil from the olive paste, since the removal of the stone changes the rheology of olive paste [30]. Other authors [31][32] have shown that de-stoner technology could represent a useful sustainability tool for olive oil extraction plants. In particular, stones of the olives can be used as fuel allowing significant energy savings [33]. In a recent study [34], the nutritional characteristics of destoned olive oils have been considered. The authors concluded that destoning technology could enhance both the sensory characteristics and nutritional value of the oil. The present work revisits, in light of recent progress, the state-of-the-art of the influence of stone removal on the quality of extra virgin olive oil with particular emphasis on phenols, volatile compounds, and sensory characteristics. It is hoped to give new life to destoned technology, with a significant advantage for the quality of the extra virgin olive oil and the sustainability of the system. It is now evident, that the interest in olive oil from stone removal is growing, since this technology allows a better working capacity, decreases waste generation, and improves virgin olive oil quality. These content will help olive oil producers to do the best choice for enhancing the qualitative characteristics of the product. An ulterior goal of this work is also to represent an important resource for scientists. It can offer inspiration for one’s own research to other researchers. Finally, it is noteworthy to report that in destoned olive oil production there are by-products with a lower environmental impact. In fact, due to the stones being about 25% of the total olive paste volume, with the stone removal, the solid waste processing quantity is considerably lesser [32].

2. Fruit Characteristics Affecting Destoning

The virgin olive oil composition depends primarily on olives characteristics, bonded on many parameters such as cultivar, ripening phase, and environmental conditions. An important role is played by the size of the olives; large olives are more suitable for the destoner machine. In fact, if the pulp is low, an excessive pulverization of the stone occurs. This, by increasing the adsorbing capacity, causes the loss of the oily fraction. It follows that the pulp must be thick and the stone small [35]. Kartas et al. [36] showed that the genetic features of a variety have a significant impact on the pulp/stone ratio. Varieties with a high fruit weight had a high pulp/stone ratio (8.25 to 6.07), while those with small fruits had a lower pulp/stone ratio (4.40). An experiment was carried out to study the influence of different amounts of irrigation water to olive trees of Coratina and Dolce cultivars [37]. The authors found that the features of olive trees were mostly influenced by irrigation; thus, the pulp/stone ratio gradually decreased with a lowering amount of water during irrigation. Morales-Sillero, Fernández and Troncoso [38] studied different doses of N-P-K fertilizer, and its effect on nutrient concentrations, yield, and oil quality. The fruit weight and pulp/stone ratio increased with fertilizer dose. However, olive oil quality was negatively affected by increasing fertilizer: polyphenol total content, bitterness, oxidative stability, and the relation of monounsaturated/polyunsaturated fatty acids decreased. Rosati, Caporali and Paoletti [39] observed that olive trees treated with N and K fertilization showed an increase in fruit weight and pulp/stone ratio. Another study evaluated how all qualitative characteristics of olive oil were influenced by foliar application with magnesium and potassium. Results showed that the pulp/seed ratio of olive fruits significantly increased after the treatments [40]. As regards the harvesting methods, many harvesting methods exist, and the choice depends on many factors [41]. Hand-picking is the slowest and most expensive method, but it allows the producer to get the best quality of the fruit. Ahmad [42] studied the performance of mechanical systems for the olive harvest and how they influenced the quality of the final product. Results revealed that mechanical harvesting increased productivity, but caused higher percentages of fruit damage, with respect to that obtained when the olives were manually harvested. However, divergences between the data reported in several studies have been found. Some researchers [43] compared different systems of harvesting olives from the tree (manual and mechanical). These studies have shown that mechanical harvesting has achieved the best results, with labor and time savings. Mechanically harvested olives were more intact than those harvested with other systems and have produced oil of high quality. The right choice of harvesting method is very important and must be taken not to damage the olives. This is one of the key points for obtaining good results from the use of destoner technology. In this regard, it is important to underline that, the damages caused to fruits due to errata harvesting have harmful effects on endogenous oxidative enzymes and negative consequences on oil quality. In all these cases, the enforcement of the destoning cannot assure the mentioned positive effects [34]. Based on the considerations made, destoning technology should be supported by suitable agronomic practices.

3. Importance of the Olives Endogenous Enzymes

To evaluate the impact of the de-stoner technology on the olive oil quality, the knowledge of how the olive’s endogenous enzymes act represents a piece of indispensable information [25]. Olives are made up of the exocarp or peel, the mesocarp or pulp, and the endocarp or fossa. There are numerous studies concerning enzymes, including lipase, peroxidase, glycosidase, lipoxygenase, and polyphenol oxidase [44][45][46]. The effects of the use of de-stoner are linked to the different sharing of enzymes in the various sections of the olive. The presence of peroxidase (POD) concentrated mainly (over 98% of the whole fruit) in the olive seed was reported in several studies [14][45][47][48]. Therefore, the exclusion of the seeds reduces the phenomena of enzymatic oxidation, especially POD oxidize main phenolic compounds, localized principally in the pulp. So, the destoned process excluding olive seeds with high peroxidase activity cut down the enzymatic degradation of phenols, and the resulting oils have higher phenol content with better oxidative stability than those obtained by whole drupes [49][50][51][52]. Polyphenoloxidase (PPO) is another endogenous enzyme of olive fruit, it is localized in the thylakoids and mitochondria. It is interesting that in the drupe mesocarp, PPO activity widely carries out its chemical activity [11][45]. However, among the enzymes, PPO plays an important role in the oxidation of phenolic substances during crushing [49]. PPO and POD can oxidize both the phenolic glucosides present in the drupe and the aglycone phenols that are formed during the processing technology to obtain the oil [48]. For this reason, the reduction of POD obtained by removing the stones had a great influence on the characteristics of the products. Lavelli and Bondesan [50] evaluated the effect of olive stone removal in six monovarietal extra virgin olive oils. The study showed that the effect of destoning was variety-dependent, and it was concluded that an acknowledgment of the endogenous enzyme heritage could be important in the management production of destoned extra virgin olive oil. Lipoxygenase (LOX) is among the endogenous enzymes of the olive fruit, the one that catalyzes the oxidation of fatty acids, in particular, linoleic and linolenic acids, with the production of volatile compounds in oils. Already about twenty years ago, some researchers [53] highlighted that LOX is mostly concentrated in chloroplasts, thylakoids, and microsomes. Generally, in extra virgin olive oils, the LOX pathway is the main cause of volatile compounds formation, responsible for fruity flavor, freshly cut grass, green fruit or vegetables such as artichoke and tomato [49]. Servili et al. [11] evaluated that the stone removal influences the LOX activity in the pastes and therefore modifies volatile composition in oils, increasing the concentration of the volatile substances, especially of hexanal, trans-2-hexenal, and C6 esters, with a consequent enhancement in “cut grass” and “floral” sensory notes [54][55]. Mazzuca, Spadafora and Innocenti [56] observed the two isoforms of oleuropein-degradative β-glucosidases present in the mesocarp of olives. The enzyme β -glycosidase, present in the olive pulp, is implicated in the conversion of secoridoids into aglycon forms, which demonstrated to be highly soluble in oil [57]. Clodoveo et al. [25] suggested that knowledge of the appropriate conditions of β-glucosidase activity, taking into account that the crushing system could inhibit the activity of β-glycosidases, with consequent decrease of phenols. It follows that endogenous enzymes of olives have a strong influence on the destoning process performance.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods11101479

References

- Ranalli, A.; Cabras, P.; Iannucci, E.; Contento, S. Lipochromes, vitamins, aromas and other components of virgin olive oil are affected by processing technology. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 445–451.

- Veneziani, G.; Sordini, B.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Urbani, S.; Di Maio, I.; Servili, M. Improvement of Olive Oil Mechanical Extraction: New Technologies, Process Efficiency, and Extra Virgin Olive Oil Quality. In Products from Olive Tree; Boskou, D., Clodoveo, M.L., Eds.; Book Citation Index in Web of Science™ Core Collection (BKCI); IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016.

- Del Caro, A.; Vacca, V.; Poiana, M.; Fenu, P.; Piga, A. Influence of technology storage and exposure on components of extra virgin olive oil (Bosana cv) from whole and de-stoned fruits. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 311–316.

- Salvador, M.D.; Aranda, F.; Gomez-Alonso, S.; Fregapane, G. Influence of extraction system, production year and area on Cornicabra virgin olive oil: A study of five crop seasons. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 359–366.

- Angerosa, F.; Basti, C.; Vito, R.; Lanza, B. Effect of fruit stone removal on the production of virgin olive oil volatile compounds. Food Chem. 1999, 67, 295–299.

- Amirante, P.; Catalano, P.; Amirante, R.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Montel, G.L.; Leone, A. Prove sperimentali di estrazione di oli extravergini di oliva da paste snocciolate. Olivo Olio 2002, 6, 16–22.

- Amirante, P.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Dugo, G.; Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A. Advance technology in virgin olive oil production from traditional and de-stoned pastes: Influence of the introduction of a heat exchanger on oil quality. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 797–805.

- De Luca, M.; Restuccia, D.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Puoci, F.; Ragno, G. Chemometric analysis for discrimination of extra virgin olive oils from whole and stoned olive pastes. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 432–437.

- Dugo, G.; Pellicano, T.M.; Pera, L.; Lo Turco, V.L.; Tamborrino, A.; Clodoveo, M.L. Determination of inorganic anions in commercial seed oils and in virgin olive oils produced from de-stoned olives and traditional extraction methods using suppressed ion exchange chromatography (IEC). Food Chem. 2007, 102, 599–605.

- Gambacorta, G.; Faccia, M.; Previtali, M.A.; Pati, S.; La Notte, E.; Baiano, A. Effects of olive maturation and stoning on quality indices and antioxidant content of extra virgin oils (cv. Coratina) during storage. J. Food Sci. 2010, 3, 229–235.

- Servili, M.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Montedoro, G. Effect of olive stoning on the volatile and phenolic composition of virgin olive oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7028–7035.

- Leone, A.; Romaniello, R.; Peri, G.; Tamborrino, A. Development of a new model of olives de-stoner machine: Evaluation of electric consumption and kernel characterization. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 81, 108–116.

- Leone, A. Olive milling and pitting. In The Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Handbook, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 117–126.

- Amirante, P.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Tamborrino, A.; Leone, A.; Paice, A.G. Influence of the crushing system: Phenol content in virgin olive oil produced from whole and de-stoned pastes. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Victor, R.P., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 69–76.

- Leone, A.; Esposto, S.; Tamborrino, A.; Romaniello, R.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Servili, M. Using a tubular heat exchanger to improve the conditioning process of the olive paste: Evaluation of yield and olive oil quality. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118, 308–317.

- Romaniello, R.; Leone, A.; Tamborrino, A. Specification of a new de-stoner machine: Evaluation of machining effects on olive paste’s rheology and olive oil yield and quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 115–121.

- Tamborrino, A.; Servili, M.; Leone, A.; Romaniello, R.; Perone, C.; Veneziani, G. Partial de-stoning of olive paste to increase olive oil quality, yield, and sustainability of the olive oil extraction process. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020, 122, 2000129.

- Leone, A.; Romaniello, R.; Zagaria, R.; Sabella, E.; De Bellis, L.; Tamborrino, A. Machining effects of different mechanical crushers on pit particle size and oil drop distribution in olive paste. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 1271–1279.

- Guermazi, Z.; Ghasallaoui, M.; Perri, E.; Gabsi, S.; Benincasa, C. Characterization of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Obtained from Whole and Destoned Fruits and Optimization of Oil Extraction with a Physical Coadjuvant (Talc) Using Surface Methodology. J. Anal. Bioanal. Tech. 2015, 6, 278–286.

- Katsoyannos, E.; Batrinou, A.; Chatzilazarou, A.; Bratakos, S.M.; Stamatopoulos, K.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Quality parameters of olive oil from stoned and nonstoned Koroneiki and Megaritiki Greek olive varieties at different maturity levels. Grasas Y Aceites 2015, 66, e067.

- Restuccia, D.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Chiricosta, S.; Puoci, F.; Altimari, I.; Picci, N. Antioxidant properties of extra virgin olive oil from Cerasuola cv olive fruit: Effect of stone removal. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2011, 23, 62–71.

- Saitta, M.; Lo Turco, V.; Pollicino, D.; Dugo, G.; Bonaccorsi, L.; Amirante, P. Oli di oliva da pasta denocciolata ottenuta da cv Coratina e Paranzana. Riv. Ital. Sostanze Grasse 2003, 80, 27–34.

- Ranalli, A.; Marchegiani, D.; Pardi, D.; Contento, S.; Pardi, D.; Girardi, F.; Kotti, F. Evaluation of functional phytochemicals in destoned virgin olive oil. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2009, 2, 322–327.

- Ranalli, A.; Contento, S. Analytical assessment of destoned and organic destoned extra-virgin olive oil. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 230, 965–971.

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Hbaieb, R.H.; Kotti, F.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Gargouri, M. Mechanical Strategies to Increase Nutritional and Sensory Quality of Virgin Olive Oil by Modulating the Endogenous Enzyme Activities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 135–154.

- Ranalli, F.; Ranalli, A.; Contento, S.; Casanovas, M.; Antonucci, M.; Di Simone, G. Concentrations of bioactives and functional factors in destoned virgin olive oil: The case study of the oil from Olivastra di Seggiano cultivar. J. Pharm. Nutr. Sci. 2012, 2, 83–93.

- Titouh, K.; Mazari, A.; Meziane, M.Z.A. Contribution to improvement of the traditional extraction of olive oil by pressure from whole and stoned olives by addition of a co-adjuvant (talc). Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids 2020, 27, 23.

- Guermazi, Z.; Gharsallaoui, M.; Perri, E.; Gabsi, S.; Benincasa, C. Integrated approach for the eco design of a new process through the life cycle analysis of olive oil: Total use of olive by-products. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1700009.

- Yorulmaz, A.; Tekin, A.; Turan, S. Improving olive oil quality with double protection: Destoning and malaxation in nitrogen atmosphere. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 637–643.

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Hbaieb, R.H. Beyond the traditional virgin olive oil extraction systems: Searching innovative and sustainable plant engineering solutions. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1926–1933.

- Rodrìguez, G.; Lama, A.; Rodrìguez, R.; Jiménez, A.; Guillén, R.; Fernàndez-Bolanos, J. Olive stone an attractive source of bioactive and valuable compounds. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5261–5269.

- Souilem, S.; El-Abbassi, A.; Kiai, H.; Hafidi, A.; Sayadi, S.; Galanakis, C.M. live oil production sector: Environmental effects and sustainability challenges. In Olive Mill Waste: Recent Advances for Sustainable Management; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–28.

- Pattara, C.; Cappelletti, G.M.; Cichelli, A. Recovery and use of olive stones: Commodity, environmental and economic assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 1484–1489.

- Restuccia, D.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Corbo, F.; Loizzo, M.R. De-stoning technology for improving olive oil nutritional and sensory features: The right idea at the wrong time. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 636–646.

- Rosati, A.; Cafiero, C.; Paoletti, A.; Alfei, B.; Caporali, S.; Casciani, L.; Valentini, M. Effect of agronomical practices on carpology, fruit and oil composition, and oil sensory properties, in olive (Olea europaea L.). Food Chem. 2014, 159, 236–243.

- Kartas, A.; Chliyeh, M.; Touati, J.; Ouazzani Touhami, A.; Gaboun, F.; Benkirane, R.; Douira, A. Evaluation of bio-agronomical characteristics of olive fruits (Olea europaea L.) of the introduced varieties and local types grown in the Ouazzane areas (Northern Morocco). Int. J. Adv. Pharm. Biol. Chem. 2016, 5, 39–43.

- Atta, N.M.M.; Mohamed, E.; Ahmed, A.A.; Gourgeose, K.G. Influence of Different Rates of Irrigation to Olive Trees on Fruits Yield, Quality and Sensory Attributes of Olive Oil Output. Ann. Agric. Sci. Moshtohor J. 2019, 57, 67–76.

- Morales-Sillero, A.; Fernández, J.E.; Troncoso, A. Pros and Cons of Olive Fertigation: Influence on Fruit and Oil Quality. ISHS Acta Hortic. 2011, 888, 269–276.

- Rosati, A.; Caporali, S.; Paoletti, A. Fertilization with N and K increases oil and water content in olive (Olea europaea L.) fruit via increased proportion of pulp. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 192, 381–386.

- Mahmoud, T.S.M.; Mohamed, E.S.A.; El-Sharony, T.F. Influence of Foliar Application with Potassium and Magnesium on Growth, Yield and Oil Quality of “Koroneiki” Olive Trees. Am. J. Food Technol. 2017, 12, 209–220.

- Mele, M.A.; Islam, M.Z.; Kang, H.M.; Giuffrè, A.M. Pre-and post-harvest factors and their impact on oil composition and quality of olive fruit. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2018, 30, 592–603.

- Ahmad, R.L. Efficiency of Mechanical Tools for Olive Harvest and Effect on Fruit Quality. In Proceedings of the ISHS Acta Horticulturae 1199, VIII International Olive Symposium, Split, Croatia, 10 October 2016; 2018.

- Abenavoli, L.M.; Proto, A.R. Effects of the divers olive harvesting systems on oil quality. Agron. Res. 2015, 13, 7–16.

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Dipalmo, T.; Schiano, C.; La Notte, D.; Pati, S. What’s now, what’s new and what’s next in virgin olive oil elaboration systems? A perspective on current knowledge and future trends. J. Agric. Eng. 2014, 193, 49–58.

- García-Rodríguez, R.; Romero-Segura, C.; Sanz, C.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Pérez, A.G. Role of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in shaping the phenolic profile of virgin olive oil. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 629–635.

- Sanchez-Ortiz, A.; Romero-Segura, C.; Sanz, C.; Perez, A.G. Synthesis of volatile compounds of virgin olive oil is limited by the lipoxygenase activity load during the oil extraction process. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 812–822.

- Luaces, P.; Romero, C.; Gutierrez, F.; Sanz, C.; Perez, A.G. Contribution of olive seed to the phenolic profile and related quality parameters of virgin olive oil. J. Scence Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2721–2727.

- Peres, F.; Martins, L.L.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Influence of Enzymes and Technology on Virgin Olive Oil Composition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3104–3126.

- Cerretani, L.; Baccouri, O.; Bendini, A. Improving of oxidative stability and nutritional properties of virgin olive oils by fruit de-stoning. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech 2008, 19, 21–23.

- Lavelli, V.; Bondesan, L. Secoiridoids, tocopherols, and antioxidant activity of monovarietal extra virgin olive oils extracted from destoned fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1102–1107.

- Mulinacci, N.; Giaccherini, C.; Innocenti, M.; Romani, A.; Vincieri, F.; Marotta, F.; Mattei, A. Analysis of extra virgin olive oils from stoned olives. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 662–670.

- Servili, M.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Di Maio, I.; Veneziani, G.; Selvaggini, R. New approaches to virgin olive oil quality, technology, and by-products valorization. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 1882–1892.

- Salas, J.J.; Sanchez, J.; Ramli, U.S.; Manaf, A.M.; Williams, M.; Harwood, J.L. Biochemistry of lipid metabolism in olive and other oil fruits. Prog. Lipid Res. 2000, 39, 151–180.

- Kalua, C.M.; Allen, M.S.; Bedgood, D.R., Jr.; Bishop, A.G.; Prenzler, P.D.; Robards, R. Olive oil volatile compounds, flavour development and quality: A critical review. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 273–286.

- Servili, M.; Esposto, S.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Di Maio, I.; Sordini, B.; Selvaggini, R.; Montedoro, G.; Angerosa, F. Volatile compounds of virgin olive oil: Their importance in the sensory quality. In Handbook of Advances in Olive Resources; Berti, L., Maury, J., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Kerala, India, 2009; ISBN 978-81-7895-388-5.

- Mazzuca, S.; Spadafora, A.; Innocenti, A.M. Cell and tissue localization of β-glucosidase during the ripening of olive fruit (Olea europaea) by in situ activity assay. Plant Sci. 2006, 171, 726–733.

- Velázquez-Palmero, D.; Romero-Segura, C.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Hernandez, L.; Vaistij, F.E.; Graham, I.A.; Pérez, A.G.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M. An Oleuropein β-Glucosidase from Olive Fruit Is Involved in Determining the Phenolic Composition of Virgin Olive Oil. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1902.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!