Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Environmental Studies

Food conservation is an issue of global importance. In unstable conditions such as pandemics and wars, clean plate campaigns have been developed to limit food waste around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic threatens global food security and has created an urgent need for food conservation

- China

- COVID-19

- food waste

1. Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral interventions gained the attention of policymakers around the world in 2010 [47,48]. In the field of food waste, one main type of behavioral intervention has been the dissemination of information, which has helped to change wasteful behavior [49]. However, the effectiveness of different messages may differ. Zhang et al. [50] stated that interventions intended to provide information are important, but what they say is even more important. For example, a simple prompt-style message (encouraging people not to waste food) is more effective than a message that simply states the amount of food waste [51]. Providing information about the negative effects of food waste significantly reduces food waste, whereas providing information about composting food waste generates more waste [52].

In terms of clean plate campaigns, relevant posters are available from China and the US, but not from Korea, by searching the Google and Baidu engines. As shown in Figure 1, the posters at the top are from the US Food Administration and the posters at the bottom are from the Chinese government and netizens.

Figure 1. Posters related to clean plate campaigns from the United States and China, with translations. (A) Food will win the war; (B) Food is the fuel for fighters; (C) Saving food is patriotic; (D) Take on demand and refuse to waste; (E) Eating up food is glorious; (F) Waste leads to failure.

As seen from these posters, the slogans of the US movement combined food with the idea of victory in war, which is related to civil rights and national honor. By contrast, the Chinese slogans focus more on personal morality and character, and cleaning the plate is always presented as a virtue or a character trait required for personal success. However, the binding force of morality is weak.

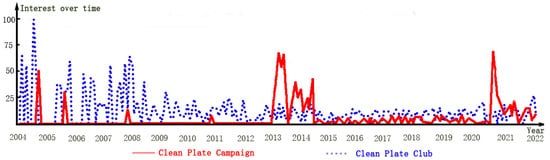

There is a lack of empirical studies comparing the effects of the two campaigns. Google Trends can show search interest for a specific topic or term from 2004 onwards. Given the different market shares held by Google in China and the US, this paper could not directly compare specific values of interest. As shown in Figure 2, although the American Clean Plate Club was originally launched in 1917, the public’s interest in the topic has never faded. The geographical areas of interest are concentrated in Canada and the USA. Interest in China’s Clean Your Plate Campaign peaked in January 2013 and August 2020, coinciding with Xi Jinping’s two public statements about limiting food waste. This is consistent with the results of the Baidu Index (the Baidu Index is the big data analysis platform of Baidu, which is currently the most popular search engine in China. Baidu index is similar to Google Trends). The Baidu Index shows that there were very few searches or reports at other times, indicating that attention to CYPC in China has been sporadic rather than continuous. Empirical studies have found that CYPC I has had limited effects [53,54]. There have not been enough studies on the effect of CYPC II.

Figure 2. Interest over time in clean plate movements according to Google Trends.

In addition to information-based interventions, Metcalfe et al. [55] summarized other nudge interventions: placement/convenience and variety/portions. Adams et al. [56] discovered a relationship between the location of a salad bar and the waste of fruit and vegetables. Changing plate and portion sizes are also effective at limiting food waste. One experiment indicated that reducing plate size can reduce food waste by 19.5% [57]. Wansink and Van Ittersum [58] found that buffet diners with large plates wasted 135% more food than those with smaller plates. Furthermore, permanent (i.e., hard plastic) plates [59], the introduction of fridge cameras or food sharing apps [60], and interventions by Home Labs (a collaborative experiment with householders) [61] were also reported to be effective.

2. Cultural Factors

Diet composition, consumption norms, and the significance of food vary widely between countries and are culturally specific [62]. Food habits are determined by multiple stimuli pertaining to the dietary framework of a particular culture or religion [63].

Some scholars link religious beliefs to food waste [64]. Religion has a positive influence on sustainable consumption practices [65,66]. One study revealed the significant impact of religiosity on attitudes and subjective norms about food waste reduction [67]. Aschemann-Witzel et al. [68] indicated that religious beliefs are a critical factor when it comes to the degree of motivation to avoid food waste. In general, religions discourage food waste. In Christianity, one passage in the New Testament states: “When they had all had enough to eat, Jesus said to his disciplines, ‘Gather the pieces that are left over. Let nothing be wasted’” (John 6:12 [NIV]). Similarly, Judaism has the Talmudic concept of bal tashchit, which can be interpreted as “thou shalt not waste” [69]. In the case of Islam, the Holy Quran states: “eat and drink, but don’t waste. Indeed, He likes not the wasteful”. In this religion, wasting food is a sin and an act of ingratitude; this perspective has proven to be one of the strongest drivers of reducing food waste [44]. However, it was discovered that restrictive religious norms (e.g., rules about food consumption and fasting) lead to greater food waste [70]. For example, Elmenofi et al. [71] found that food waste increases during the fasting month of Ramadan (an Islamic month of fasting) in Egypt. A review found that nearly 25–50% of the food prepared in some Arabic countries during Ramadan is wasted due to over-preparation [72].

However, Elshaer et al. [73] found that religiosity had a very weak negative influence on people’s intention to waste food, whereas food consumption culture has a significant positive influence on people’s intention to waste food. The characteristics of a nation’s culture can affect the quantity of wasted food [74,75]. First, different cultures develop different attitudes towards food and food waste. Not all food waste is considered unacceptable in all cultures. Since meat is still at the center of most Danish dishes, it is more culturally acceptable in Denmark to throw away foods that are thought of as having lower status, like bread and vegetables [76]. Moreover, it is considered inappropriate to finish all the food on one’s plate in Abu Dhabi [74,77]. In terms of moral judgments, the Masai think food wasting is more immoral than the Yali and the Poles [78]. Second, cultural contexts shape eating habits [15]. French traditions of moderation (versus American traditions of abundance) and a focus on quality (versus quantity) mean that the French eat less than Americans [79]. The Chinese dine together, and the dishes are often served in large portions. Conversely, Westerners tend to eat separately, and each person is assigned a limited amount of food on their plate. Third, cultural norms influence portion sizes [80,81]. China is influenced by collectivism. Each dish is served in a large portion to ensure that everyone has enough. By comparison, Japanese food is served in small portions. Japanese culture contains the concept of mottainai, which expresses the regret of wasting something valuable [82].

Two cultural values, namely hospitality and face-saving (in Chinese, mianzi), play an important role in food waste across many cultures. In terms of hospitality, Saudis and Arabs place a high value on generous hospitality. They provide guests with large quantities of food to exceed their expectations [73,83]. Slovenians and Chinese people also offer guests more food than is necessary [84,85]. Elshaer, Sobaih, Alyahya, and Abu Elnasr [73] have noted that this culture of serving a lot of food to show hospitality means that people are highly likely to waste food. There is also the concept of being a “good provider”, which means that one shows hospitality to family and friends by providing lots of food. Various scholars argue that the “good provider” mentality is a barrier to tackling the problem of food waste [85,86]. Wang, McCarthy, and Kapetanaki [85] have stated that expressions of hospitality through food are central to the social fabric of most societies and that “good provider” norms, along with socio-cultural factors, help to explain food waste behavior.

The American preacher Smith [87] has stated that face-saving is the most basic and important characteristic of the Chinese people. Face-saving significantly influences food waste [88,89]. In China, the concept of “face” is a highly valued quality related to reputation and ego. It is gained through success or boasting [90]. Specifically, preparing or ordering excessive meals is considered a sign of affluence or status, which allows people to “gain face”. Doing the opposite causes people to “lose face”. Moreover, China is a society based on favor (in Chinese, renqing), “favor” often refers to resources (tangible goods such as money and food, or intangible things such as help and opportunities) that are exchanged during interactions. This involves exchanges in a society of acquaintances, relying on moral constraints rather than regulatory constraints [91]. Treating people to dinner is the most basic way to exchange benefits, whether one is asking for a favor or thanking someone for help. Over-ordering is a common way of showing sincerity. Wang et al. [92] argue that when food is considered to be a social tool rather than a delicacy or necessity, food waste becomes an issue of low concern.

3. Political Factors

Culliford and Bradbury [93] found that consumers in the UK remain resistant to some aspects of sustainable diets. They highlighted the fact that policy action is required to enable behavioral change. Many countries have implemented policies or programs to limit food waste. According to a report produced in 2011, more than a hundred food waste prevention initiatives have been launched in EU countries [94]. Policy factors have been shown to curb food waste to a large extent [95,96]. Revised meal standards and policies have been found to significantly lower plate waste in school cafeterias [97]. Secondi, Principato, and Laureti [12] have emphasized the need for public–private partnerships and diverse policy interventions at the local level (i.e., targeting community-based interventions).

In China, the requirement to improve laws and regulations has appeared eight times in the previous 26 policies. It was first mentioned in the 1996 policy. It was not until 29 April 2021, that China’s first official anti-food waste law was enacted. Other countries have also enacted laws against food waste, such as France, Italy, and Japan. These countries are compared in Table 1. For its categories of analysis, this study referred to Vittuari [98], adopting the approach, instruments, and stages used in that study. Policy approaches to food waste prevention can be classified as suasive (e.g., communication campaigns, educational activities) or regulatory (e.g., legal obligations to donate surplus food, mandatory standards). Instruments can be market-based (e.g., subsidies, taxes, and tax concessions) or public services (e.g., food donation infrastructures) [98]. Food waste prevention pyramids, such as disposal, recovery, recycling, reuse, and prevention (ranked from least to most effective) have also been introduced as ways of studying the effectiveness of anti-food waste laws and policies [99].

Table 1. Anti-food waste laws in different countries.

| France (https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000032036289, Accessed on 16 March 2022) | Italy (https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2016/08/30/16G00179/sg, Accessed on 16 March 2022) | Japan (https://perma.cc/LK8H-A8KU, accessed on 16 March 2022) | China (http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/202104/83b2946e514b449ba313eb4f508c6f29.shtml, Accessed on 16 March 2022) | |

| Adoption time | 11 February 2016 | 19 August 2016 | 24 May 2019 | 29 April 2021 |

| Main approach | Regulatory | Suasive | Suasive | Suasive |

| Main instrument | Public services | Market-based | Public services | Public services |

| Main objects | Retailers, charities | General public, catering service providers | Governments | Governments, catering service providers |

| Main stage | Re-use, prevention | Prevention, re-use | Prevention | Prevention |

| Funding | No | Yes | No | No |

| Donations | Mandatory (Fine) | Incentive (Tax reduction) |

Supported | Guided |

| Main points | 1. Food retailers are forbidden to destroy unsold food products still fit for consumption. 2. Obligation to establish a partnership with a charity organization to donate unsold food products, for stores over 4305 square feet. |

1. Municipalities may apply a waste tax reduction for entities engaged in food donation. 2. For a donation below €15,000, no official procedures are required. 3. Donation of products that are beyond the minimum term of conservation is possible 4. The law establishes a stakeholders’ committee on food waste. |

1. Local municipalities will be urged to draft and act on their own plans. 2. October becomes the annual Food Loss Reduction Month 3. The law also sets up a body for the promotion of food loss reduction within the Cabinet Office. |

1. An anti-food waste supervision and inspection mechanism should be established. 2. Restaurants must provide small portions, display anti-waste signs, and offer packing services. 3. Prohibit the spread of content promoting food waste (overeating) or face fines. |

France requires large stores to sign agreements with charities or face hefty fines. “The law is wrong in both target and intent,” argued Jacques Creyssel, the head of a distribution organization for big supermarkets. “Big stores are already the pre-eminent food donors” [100]. Meanwhile, charities face the challenge of managing large quantities of food which are at times low-quality or inedible [101]. With extremely limited storage and distribution capacity, they must often discard uneaten food and bear the disposal costs [102]. Furthermore, Eubanks [103] argued that public awareness campaigns and the resulting cultural changes would more effectively eliminate food waste than fines and penalties. France’s 2016 law focused on the retail sector, while the 2019 law extended to the mass catering and food industry.

Unlike the French law, the Italian law has instead focused on incentives. Moreover, there are five provisions of funds in the Italian law to provide support, while no specific funding is given for measures against food waste in the French law [99,104]. Busetti [105] summarized the innovative measures of the Italian law, namely the possibility of donating food after the best-before date and a significant simplification of the bureaucracy of donations. At the same time, they saw a number of constraints, such as failure to address donors’ propensity to donate, the capacity and will of charities, and the reputational risk implied by food after the best-before date [105].

Although the Japanese law specifies that it is the responsibility of both the national government and local authorities to reduce food loss, it lacks specific requirements for measures from companies or precise plans from authorities to enact such steps [106]. Japanese law thus acts as more of a rough guide. In addition to regulating governments, Chinese law gives more detailed requirements for other targets, especially catering service providers. Moreover, Chinese law also lists penalties for non-compliance but does not give objective and operational criteria for judging. Food donations are also briefly mentioned in the Chinese and Japanese laws, but these regulations are not as important or actionable as in France and Italy. Ayako [106] proposed that ambiguities related to responsibility for issues such as hygiene when providing food to charities have hindered such donations in Japan.

4. COVID-19 Factors

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, food production and consumption systems have undergone significant changes [107]. Food consumption routines and the perspective of consumers on food have also changed [108]. Specifically, lockdown and quarantine policies have forced some dietary and routine changes, such as increases in online shopping, less eating out [109], and increases in people’s culinary skills [110,111]. Researchers have also discovered a shift towards healthier diets (e.g., increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables) [112] or unhealthier diets (e.g., eating more processed foods) [113]. Other changes include an increase in the consumption of local or domestic products [111,114], as well as weakened purchasing power (due to unemployment or pay reduction) [110].

Many scholars have studied the impact of the pandemic on food waste. The pandemic has led to stockpiling and panic buying [115,116]. Non-perishable food items were prioritized by stockpilers [110]. For example, Ben Hassen et al. [117] have shown the extent of panic purchasing in Lebanon, with 73.13 percent of respondents reporting that they stocked up on food once COVID-19 became serious. The same phenomenon was observed in Morocco [118]. People’s reasons for stockpiling were the fear of food shortages and price rises, an attempt to reduce store visits to limit exposure to COVID-19 [1,119], and a need to feel in control of a perilous situation [120]. Cosgrove et al. [121] found that food stockpiling was a predictor of increased overall food waste. Recent data show that individuals did not consume a good proportion of their stockpiled food, leading to increased waste [122,123]. Other reasons for increased food waste include unappetizing taste and food exceeding the expiration date or rotting [124].

However, most studies show that the pandemic has led to a reduction in food waste and a shift towards more sustainable patterns of consumption [110,125,126]. These studies mostly took the form of online questionnaires or self-monitored reports. Based on data derived from the waste management department in Malaysia, one study estimated that there was a 15.1% decrease in food waste during the lockdown in the country [127]. There are many possible reasons for this decrease in food waste. First, COVID-19 improved people’s awareness about food and food waste [114,128,129]. Second, the COVID-19 lockdown improved people’s ability to manage food, encouraging them to plan their food shopping more effectively, enhance their in-house food storage, and use up more leftovers [120,130]. Third, Pappalardo et al. [131] found that concerns about the impact that the pandemic could have on the waste management system and the desire not to add pressure to that system both helped to decrease food waste.

Overall, the impact of COVID-19 on food waste has varied from country to country. This is due to epidemiological circumstances, the baseline socio-economic situation, and the shock resilience of different countries [116]. Rodgers et al. [132] found that people in the US reduced their relative food waste to a greater extent than people from Italy. However, the effects have also varied from person to person. Amicarelli et al. [133] identified three different clusters after the COVID-19 lockdown: some people wasted more food and some wasted less. Armstrong et al. [134] found that participants with food security wasted a smaller percentage of purchased and cooked foods compared to participants without food security. Other influencing factors included age, gender, household composition, and employment status [135,136,137,138].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14084699

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!