The Mediterranean diet varies by country and region, so it has a range of definitions. In general, however, it is high in vegetables, fruits, legumes (such as beans), nuts, cereals, fish and unsaturated fats (such as olive oil). It usually includes a low intake of meat and dairy foods. In particular, some plants are characteristic of the Mediterranean vegetation; some have been present for thousands of years, such as olive trees, walnuts, oregano, pomegranates, onions and others including various citrus species. Polyphenols have a typical molecular structure with one or more aromatic rings, and one or more double bonds are present in the molecule. This structure guarantees an antioxidant action for all classes, as there is delocalization of the free radical itself, with consequent antioxidant activity.

1. Introduction

Angel Keys, a biologist and physiologist who based his conclusions on his studies focusing on the dietary habits of people living in Southern Italy, was the first to present the phrase “Mediterranean diet” to the popular imagination, investing it with a scientific and cultural meaning. Now, following the joint candidacy of Italy, Spain, Greece and Morocco, followed by Cyprus, Croatia and Portugal, it has the recognition of not only UNESCO, but also of the WHO and FAO. The Mediterranean diet varies by country and region, so it has a range of definitions. In general, however, it is high in vegetables, fruits, legumes (such as beans), nuts, cereals, fish and unsaturated fats (such as olive oil). It usually includes a low intake of meat and dairy foods. In particular, some plants are characteristic of the Mediterranean vegetation; some have been present for thousands of years, such as olive trees, walnuts, oregano, pomegranates, onions and others including various citrus species

[1]. The Mediterranean diet represents one of the first examples of a positive correlation between diet and cardiovascular health; in fact, a diet that involves the frequent eating of fruit and vegetables, possibly in season, in addition to seeds and olive oil, has been shown to exhibit significant benefits in health terms, resulting not only in preventing cardiovascular disease, but also diabetes, obesity and even various forms of cancer

[2][3][4][5], although the dietary polyphenol intake in Europe seems to be high in the north

[6]. This effect can be explained, at least in part, by the regular and varied intake of food polyphenols that characterize the Mediterranean diet. Although there is no set recommended daily dose, polyphenols have an important role in modulating and preventing various diseases, such as cardiovascular

[6], as well as inflammatory diseases such as arthritis

[7]. Probably the most important actions by polyphenols are carried out in the regulation and management of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and immunomodulation. The pathways that are influenced by much of them are those of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein Kinase (MAPK) and arachidonic acids and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases/protein kinase B (PI3K/AkT) as an inhibitor. On the other hand, they upregulate superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) expression: GPR40

[8][9][10][11].

Polyphenols are very often linked to the colors of the plants that contain them. They are present in practically all plant species and in various parts of the plant itself, especially in the leaves, fruits and roots

[12]. On the other hand, while showing promising in vitro activity, they often present the obstacle of bioavailability, which does not always make them so useful if tested directly on humans. Polyphenols have a typical molecular structure with one or more aromatic rings, and one or more double bonds are present in the molecule. This structure guarantees an antioxidant action for all classes, as there is delocalization of the free radical itself, with consequent antioxidant activity.

[12]. Together with this, polyphenols have a genomic and epigenomic action, in fact there are numerous studies that underline their regulatory action, among others, on NF-κB, MAPK and nuclear factor erythroid related factor 2 (Nrf2)

[11][13][14]. In addition to that, they show epigenetic activity in modulating microRNAs expression and from this point of view the microRNAs could represent a useful evaluation tool to study polyphenols action in human.

2. Dietary Sources

2.1. Naringenin

Naringenin is especially abundant in rosemary (55.1 mg/100 g) and present in grapefruit juice (37.76 mg/100 mL), red wine (0.75 mg/100 mL) and orange juice (0.07 mg/100 mL) (

Figure 1). Naringenin is a flavonoid belonging to the subclass of flavanones, also often found in food in its glycosides form.

[15].

Figure 1. Main foods and beverages that contain naringenin, according to the database Phenol-Explore (

http://phenol-explorer.eu/ accessed on 29 January 2021) and USDA Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods (

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ accessed on 13 February 2021).

2.2. Apigenin

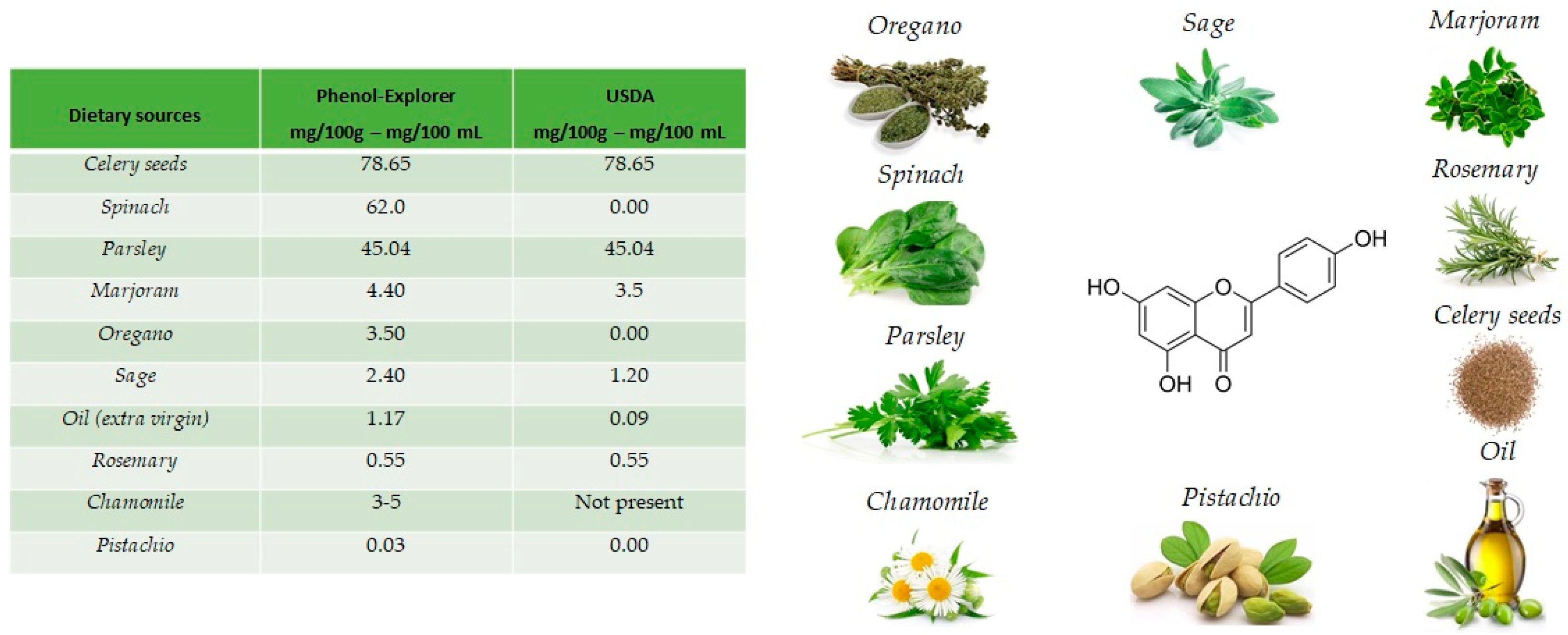

The name apigenin derives from the genus Apium in the Apiaceae also known as Umbelliferae and is found as a unique ingredient in chamomile (

Matricaria chamomilla), an annual herb native to western Asia and Europe. Drinks prepared from chamomile contain from 0.8% to 1.2% of apigenin. Apigenin is abundant in a variety of other dietary sources

[16], including fruits and vegetables (

Figure 2), such as celery seeds (78.65 mg/100 g), spinach (62.0 mg/100 g), parsley (45.04 mg/100 g), marjoram (4.40 mg/100 g), Italian oregano (3.5 mg/100 g), sage (2.40 mg/100 g), chamomile (3 to 5 mg/100 g) and pistachio (0.03 mg/100 g), but the richest sources are the respective dried sources.

[17].

Figure 2. Main foods that contain apigenin, according to the database Phenol-Explore (

http://phenol-explorer.eu/ accessed on 29 January 2021) and USDA Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods (

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ accessed on 13 February 2021).

2.3. Kaempferol

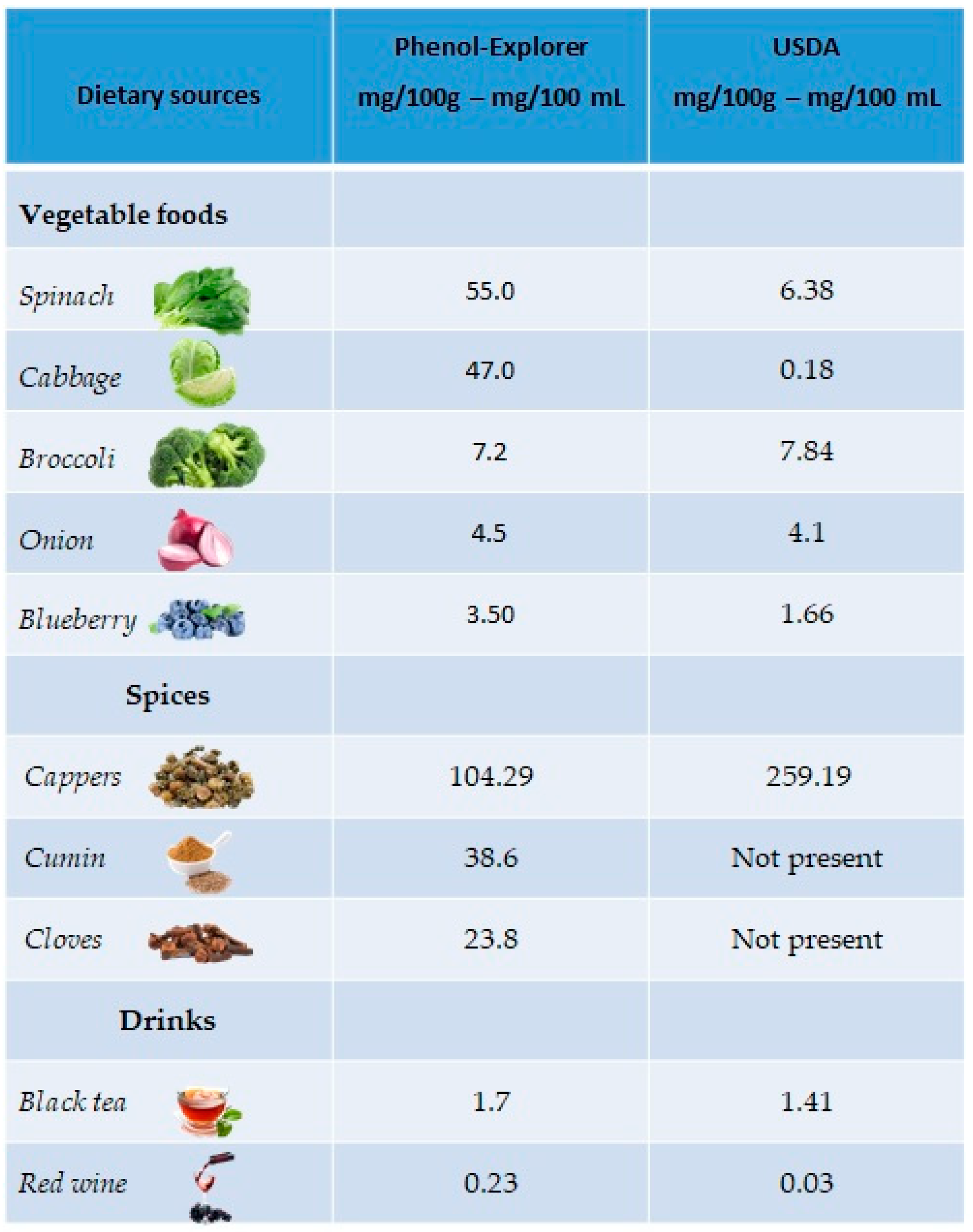

The richest plant sources of kaempferol are green leafy vegetables, such as spinach (55 mg/100 g), cabbage (47 mg/100 g) and broccoli (7.2 mg/100 g), but also in onions (4.5 mg/100 g) and blueberries (3.17 mg/100 g). Regarding drinks, kaempferol is mainly present in black tea (1.7 mg/100 mL) and red wine (0.23 mg/100 mL). A good percentage is also present in spices such as capers (104.29 mg/100 g), cumin (38.6 mg/100 g) and cloves (23.8 mg/100 g) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Main foods and beverages that contain kaempferol, according to the database Phenol-Explore (

http://phenol-explorer.eu/ accessed on 29 January 2021) and USDA Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods (

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ accessed on 13 February 2021).

2.4. Hesperidin

Hesperidin and its aglycone, hesperetin, are two flavonoids, which together with rutin and quercetin, are the main compounds of citrus fruits and, for this reason, this compound is called “citroflavonoid”. It is present mainly in blood orange (43.71 mg/100 mL), mandarin juice (36.11 mg/100 mL), blond orange juice (25.85 mg/100 mL), lemon (17.81 mg/100 mL) and lime (13.41 mg/100 g) (Figure 4). The presence of this compound has also been detected in plants; a high value is reported in peppermint (480.65 mg/100 g).

Figure 4. Main foods that contain hesperidin according to the database Phenol-Explore (

http://phenol-explorer.eu/ accessed on 29 January 2021) and USDA Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods (

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ accessed on 13 February 2021).

2.5. Ellagic Acid

Ellagic acid, a dilactone of the dimer gallic acid, is a polyphenol found in fruit and vegetables. Some foods contain a more complex version called ellagitannin, which will be converted into ellagic acid by organism. Ellagic acid is prevalent in berries (

Figure 5). Foods high in ellagic acid are chestnut (735.44 mg/100 g), blackberries (43.67 mg/100 g), black raspberries (38 mg/100 g), walnuts (28.50 mg/100 g), cloudberries (15.30 mg/100 g), pomegranate juice (2.06 mg/100 mL), strawberries (1.24 mg/100 g), red raspberries (1.14 mg/100 g) and muscadine grape (0.90 mg/100 g)

[18]. Ellagic acid is synthetized by plants as a defense mechanism against infections and parasites.

Figure 5. Structure and main foods that contain ellagic acid, according to the database Phenol-Explore (

http://phenol-explorer.eu/ accessed on 29 January 2021). There is no value reported for the USDA Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods (

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ accessed on 13 February 2021).

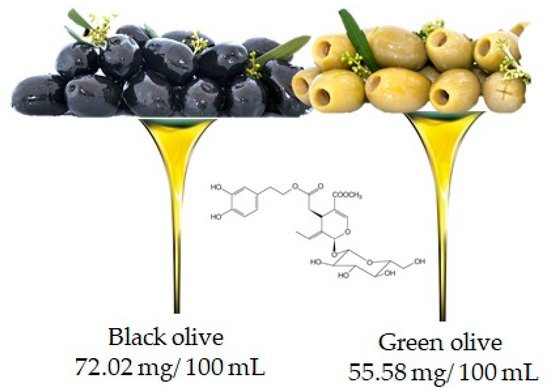

2.6. Oleuropein

Oleuropein is the molecule responsible for the bitter taste of olives and is the most common phenolic component in the leaves, seeds, pulp and skin of unripe olives. Although abundant, this compound undergoes hydrolysis during fruit ripening leading to the production of other important compounds such as hydroxytyrosol and ester derivatives

[19]. It is important to underline that the oleuropein content may also depend on the variety of the olive (in fact black and green olives contain 72.02 mg/100 mL and 55.58 mg/100 mL, respectively (

Figure 6)), but also, and above all, on the processing techniques used to obtain the oil

[20].

Figure 6. Olive is the main food that contains oleuropien, according to the database Phenol-Explore (

http://phenol-explorer.eu/ accessed on 29 January 2021). There is no value reported for the USDA Database for the flavonoid content of selected foods (

https://www.ars.usda.gov/ accessed on 13 February 2021).

3. Chemistry

Polyphenols are natural compounds synthesized exclusively by plants and characterized by two phenyl rings at least and one or more hydroxyl substituents. This description comprehends a large number of heterogeneous compounds with reference to their complexity. All phenolic compounds are synthesized through the phenylpropanoid pathway (

Figure 7), starting from the amino acid phenylalanine

[21], which is, in turn, a product of the shikimate pathway; the latter links carbohydrate metabolism to the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids and secondary metabolites shikimate pathway

[22].

Figure 7. Phenylpropanoid Pathway. The metabolites of the shikimate pathway and p-coumaroyl CoA are shaded in grey.

The phenylpropanoid pathway leads to different classes of compounds which can be can be simply classified into flavonoids and nonflavonoids, or be subdivided in many subclasses depending on the structural diversity. This arises from the number of phenol units within the structure, substituent groups, variations in hydroxylation pattern and/or the linkage type between phenol units.

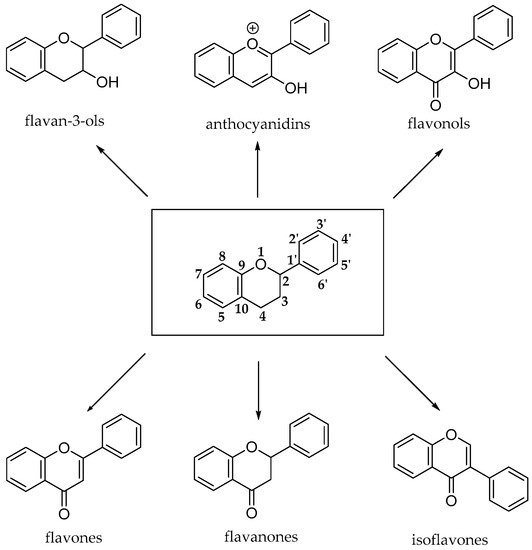

The flavonoid pathway (calchone synthase) leads to the synthesis of six major classes of metabolites, such as flavonols, flavan-3-ols, anthocyanidins, proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins. All these compounds share the basic structure of diphenyl propanes (C6-C3-C6), in which phenolic rings (ring A and ring B) are usually linked by a heterocyclic ring (ring C), which usually is a closed pyran, as shown in

Figure 8 [23].

Figure 8. Basic structures of flavonoid subclasses.

Most flavonoids occur in edible plants and foods as β-glycosides, bound to one or more sugar units with the exception of flavan-3-ols (catechins and proanthocyanidins) and glycosylated isoflavones that are exposed to microbial β-glucosidases, which catalyze the hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond.

3.1. Naringenin

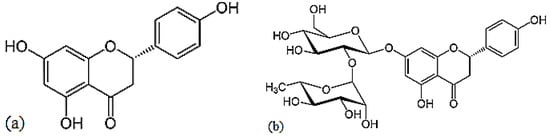

Naringenin is a flavorless, colorless flavanone with three hydroxy groups at the 7, 5 and 4′ carbons (

Figure 9)

[24]. It may be found both in the aglycol form, naringenin (a), or in its glycosidic form, naringin (b), which has the addition of the disaccharide neohesperidose attached via a glycosidic linkage at carbon.

Figure 9. Structures of naringenin (a) and naringin (b).

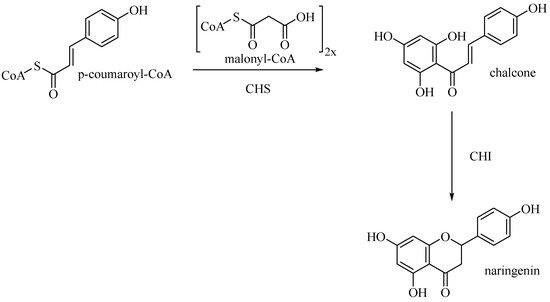

Entering the flavone synthesis pathway, enzyme chalcone synthase (CHS) catalyzes consecutive condensations of three equivalents of malonyl CoA followed by aromatization to convert starting p-coumaroyl-CoA to chalcone

[25]. Chalcone isomerase (CHI) performs stereospecific isomerization of tetrahydroxychalcone to (2S)-flavanone, which is the branch point precursor of many important downstream flavonoids, including flavones (

Figure 10).

Figure 10. Biosynthetic pathway of naringenin.

3.2. Apigenin

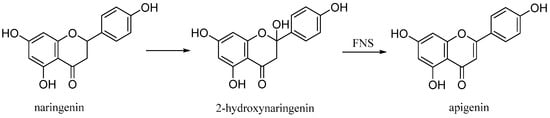

Apigenin (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone), is a natural product belonging to the flavone class that is the aglycone of several naturally occurring glycosides. It is a yellow crystalline solid that has been used to dye wool. The approximately 650 known flavones arise from flavanones by oxidative processes catalyzed by a flavanone synthase (FNS) enzyme (

Figure 11)

[26]. Two types of FNS have previously been described; FNS I, a soluble enzyme that uses 2-oxogluturate, Fe2+ and ascorbate as cofactors and FNS II, a membrane bound, NADPH dependent cytochrome p450 monooxygenase

[27].

Figure 11. Biosynthetic pathway of apigenin.

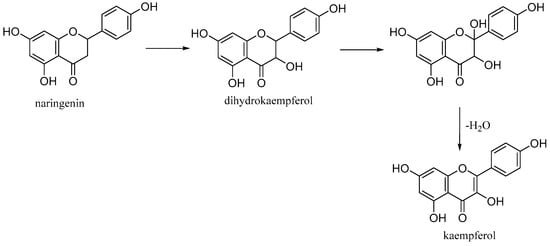

3.3. Kaempferol

Kaempferol (3,5,7-trihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one) is a natural flavonol found in common foods derived from plants and fruits. It is biosynthesized from naringenin via a 2-hydroxy intermediate (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Biosynthesis of kaempferol.

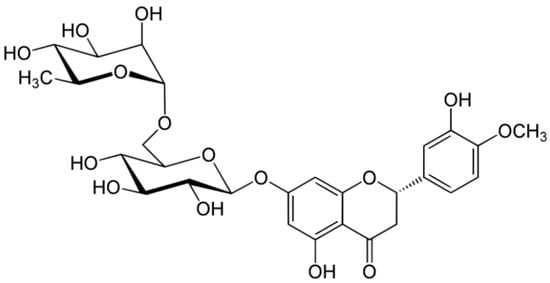

3.4. Hesperidin

Hesperidin is a flavanone glycoside found in citrus isolated in 1828 by French chemist Lebreton from the white inner layer of citrus peels (mesocarp, albedo)

[28]. The structure consists of a flavanone aglycone, hesperetin, similar to naringenin, which differs from it for the different pattern of substitution on the B ring, which is functionalized with hydroxy group on 3′ carbon and methoxy group on 4′ carbon, whereas the naringenin lacks the methoxy group (

Figure 13)

[29].

Figure 13. Structure of hesperidin.

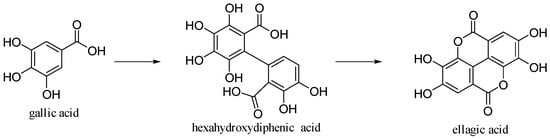

3.5. Ellagic Acid

Ellagic acid is 2,3,7,8-tetrahydroxy[l]benzo-pyrano-[5,4,3-cde]

[1] benzopyran-5,10-dione

[30]. It is formed by dimerization of gallic acid by oxidative coupling with intramolecular lactonization of both carboxylic acid groups; thus, it is a dilactone of the dimer of gallic acid (

Figure 14).

Figure 14. Gallic and ellagic acids.

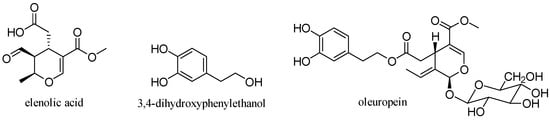

3.6. Oleuropein

Oleuropein is a glycosylated secoiridoid produced by secondary metabolism of plants and is present in all olive tissues. The term oleuropein is derived from the botanical name of the olive tree,

Olea europaea. Oleuropein is an ester of elenolic acid with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (hydroxytyrosol), which is linked to a unit of glucose by a β-glycosidic bond (

Figure 15)

[31].

Figure 15. Structure of oleuropein.

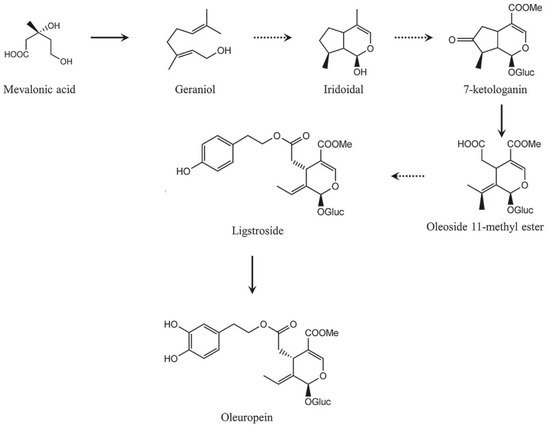

Secoiridoid conjugates that contain an esterified phenolic moiety, such as oleuropein, result from a branching in the mevalonic acid pathway in which terpene synthesis (oleoside moiety) and phenylpropanoid metabolism (phenolic moiety) merge

[32]. This is illustrated schematically in

Figure 16.

Figure 16. A simplified scheme of the oleuropein biosynthesis.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox10020328