Rapid and profound changes anticipated in the future of work will have significant implications for the education and training of occupational safety and health (OSH) professionals and the workforce. As the nature of the workplace, work, and the workforce change, the OSH field must expand its focus to include existing and new hazards (some yet unknown), consider how to protect the health and well-being of a diverse workforce, and understand and mitigate the safety implications of new work arrangements. Preparing for these changes is critical to developing proactive systems that can protect workers, prevent injury and illness, and promote worker well-being. An in-person workshop held on February 3–4, 2020 at The University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth) School of Public Health in Houston, Texas, USA, examined some of the challenges and opportunities OSH education will face in both academic and industry settings. The onslaught of the COVID-19 global pandemic reached the United States one month after this workshop and greatly accelerated the pace of change.

- expanding occupational safety and health paradigm

- future of work

- occupational safety and health professional

- training and education

- Total Worker Health

Introduction

The world is undergoing major changes in the way work is performed, the workforce, and the workplace. With the goal of increasing productivity and the greater incorporation of technology, the pace of work has intensified. While short-term, temporary employment arrangements represent greater flexibility for employers, they can translate into more precarious situations for workers; lower pay for equivalent education, skills, and experience compared to those with long-term contracts; fewer benefits; and greater turnover [1–3]. Thirty percent of the U.S. workforce now engages in nonstandard work arrangements, such as contingent work, temporary contracts, and part-time work [4]. Additionally, estimates of teleworking under the COVID-19 pandemic reached upwards of 50% of all employed U.S. adults, and it is highly likely that the decades-long trend to increased teleworking, which has been accelerated by the pandemic, will continue [5]. Future of work scenarios describe an increasing global reliance on the informal sector and hazardous work exposures that are exacerbated by work-life stress and health consequences of precarious work [6].

Factors influencing worker health and well-being now go beyond traditional occupational safety and health (OSH) hazardous exposures and include changing demographic profiles (e.g., older, more diverse), greater burden of chronic disease, varying employment arrangements including informal work with fewer protections, shifts in work organization, increased psychosocial stressors, and the role of technology and related intensification of work demands. These combine with individual health and lifestyle and factors in the home, community, and general society to affect worker health and well-being [7]. Recent years have also seen a strong movement toward measuring worker well-being as a major safety and health outcome [7,8]. Together, these changes underscore the need for an expanded focus for OSH that goes beyond simply summing workplace illness and injury prevention with health promotion [9]. This expanded focus can significantly transform how we train future OSH professionals, conduct OSH research, and design forward-thinking policies to maximize worker health and well-being.

The NIOSH Future of Work Initiative and the Total Worker Health® Approach

The NIOSH Future of Work (FOW) Initiative was launched in 2019 and applies the Total Worker Health® (TWH) framework by encouraging collaboration across organizational policies, programs, and practices. Central to both of these NIOSH futures-oriented priorities is the concept of worker well-being, which integrates the traditional OSH goal of protecting workers from occupational hazards with the promotion of health and illness prevention in the workplace and is being operationalized by NIOSH through its TWH program [10,11].

Towards an Expanded Focus for Occupational Safety and Health

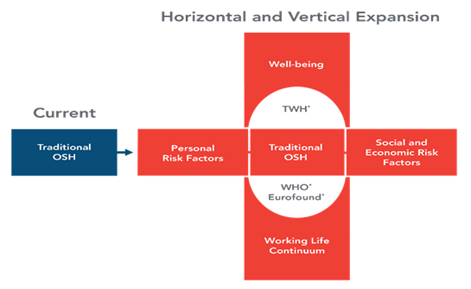

The OSH field will need an expanded, more holistic focus to address challenges and changes posed by FOW scenarios to prepare the professionals of the future. This paradigm shift challenges traditional OSH systems by focusing on worker well-being as an outcome, goes beyond the prevention of workplace injury and illness or health promotion, and expands the types of hazards typically considered in the traditional OSH paradigm. Beyond this, though, we need a more expansive paradigm to include greater recognition of both individual worker and workforce well-being as important OSH outcomes. Embracing this paradigm shift mandates a more expansive, systems thinking approach to better integrate traditional OSH with personal and socioeconomic risk factors, both horizontally (broadening the range of factors to examine their impact on health) and vertically (from a short-term, single job perspective to a work life continuum perspective encompassed by the overarching concept of well-being) [9]. The model for this expanded focus for OSH was modified from Schulte et al. [9,12] and is presented in Figure 1.

This will require greater interprofessionalism, collaborative organizational leadership, proactive company policies, accountability, training, and engagement of management and employees, as well as following benchmarks over time and identifying opportunities for early corrective or enhancing interventions [13]. Moreover, as the paradigm expands, there will be a need for greater integration of systems thinking and transdisciplinary efforts, and for finding innovative ways to attract and train students into OSH professions. Systems thinking is the process of understanding the interconnection of elements (systems) that are organized to achieve a specific purpose [14]. Transdisciplinary efforts are those that cross multiple disciplines and professions and result in a broader and more holistic approach to problems solving strategies [15]. It is therefore likely that there will be a need for new disciplines and specialties in OSH or, at a minimum, a broader skill set and expanded training of traditional OSH professions to include occupational health psychology, human resource management, and TWH [16].

Figure 1. An expanded focus for occupational safety and health. * Horizontal and vertical expansion build on the work of WHO [17], Eurofound [18], and TWH [19.20].

Conclusions and Recommendations

The OSH professional of the future needs to take a more holistic approach that brings several opportunities to engage leadership in the development of company/agency statements of purpose that goes beyond shareholders. Academic OSH programs should develop new approaches and methods, creating opportunities for targeted and focused training that can be personalized. Training programs should also integrate OSH practice earlier in the degree pathway and re-engineer competency-based learning to achieve personalized learning objectives. Responding to shifts in historic worker characteristics will create opportunities to change human resource practices and selection practices. Unions and organized labor will need a broader agenda to both reach and represent new, non-traditional groups and remain a sustained voice for workers. OSH should pay attention to and anticipate new risks posed by different FOW challenges. How the field responds to these challenges can help address the gradual marginalization of OSH by creating a proactive rather than responsive profile.

These recommendations will help develop a roadmap toward an expanded focus for OSH, built on the traditional OSH paradigm and the TWH framework, to anticipate future education and training needs. A new approach to training OSH professionals that anticipates changes the future of work will bring is a critical next step to developing systems that not only protect workers by preventing potential injury and illness but also promote worker well-being over the work-life continuum to optimize a productive and healthy life course.

References

- Schulte, P.; Vainio, H. Well-being at work–overview and perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2010, 36, 422-429.

- Cappelli, P.H.; Keller, J.R. A study of the extent and potential causes of alternative employment arrangements. Industrial Labor Review 2013, 66, 874-901.

- Cummings, K.J.; Kreiss, K. Contingent workers and contingent health: Risks of a modern economy. JAMA 2008, 299, 448-450.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO]. Contingent workforce: Size, characteristics, earnings and benefits.; Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/669899.pdf, 2018.

- Guyot, K.; Sawhill, I.V. Telecommuting will likely continue long after the pandemic. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/04/06/telecommuting-will-likely-continue-long-after-the-pandemic/ (accessed May 14, 2020).

- Schulte, P.A.; Streit, J.M.K.; Sheriff, F.; Delclos, G.; Felknor, S.A.; Tamers, S.L.; Fendinger, S.; Grosch, J.; Sala, R. Potential scenarios and hazards in the work of the future: A systematic review of the peer-reviewed and gray literatures. Annals of Work Exposures and Health 2020, ePub ahead of print.

- Chari, R.; Chang, C.-C.; Sauter, S.L.; Sayers, E.L.P.; Cerully, J.L.; Schulte, P.; Schill, A.L.; Uscher-Pines, L. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health a new framework for worker well-being. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine 2018, 60, 589.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Measuring well-being and progress: Well-being research. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/statistics/measuring-well-being-and-progress.htm (accessed June 25, 2020).

- Schulte, P.A.; Delclos, G.; Felknor, S.A.; Chosewood, L.C. Toward an expanded focus for occupational safety and health: A commentary. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 4946.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH]. NIOSH Total Worker Health®. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/webinar.html (accessed Dec 6, 2018).

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH]. Future of Work Initiative. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/future-of-work/default.html (accessed September 14, 2020).

- Schulte, P. Towards an expanded focus for occupational safety and health. Presented at How will the future of work shape the OSH professional of the future? A workshop. Shaping the Future to Ensure Worker Health and Well-being: Shifting Paradigms for Research, Training and Policy, Houston, TX, USA, February 2020.

- Tamers, S.L.; Goetzel, R.; Kelly, K.M.; Luckhaupt, S.; Nigam, J.; Pronk, N.P.; Rohlman, D.S.; Baron, S.; Brosseau, L.M.; Bushnell, T., et al. Research methodologies for Total Worker Health®: Proceedings from a workshop. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine 2018, 60, 968-978.

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008.

- Nicolescu, B. Manifesto of transdisciplinarity. State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2002.

- Newman, L.S.; Scott, J.G.; Childress, A.; Linnan, L.; Newhall, W.J.; McLellan, D.L.; Campo, S.; Freewynn, S.; Hammer, L.; Leff, M., et al. Education and training to build capacity in Total Worker Health® proposed competencies for an emerging field. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2020, ePub ahead of print.

- Burton, J.; Kortum, E.; Abeytunga, P.; Coelho, F.; Jain, A.; Lavoie, M.; Leka, S.; Pahwa, M. Healthy workplaces: A model for action for employers, workers, policy-makers, and practitioners; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Eurofound. Sustainable work throughout the life course: National policies and strategies; Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1610en_4.pdf, 2016.

- Total Worker Health®. Hudson, H.L., Nigam, J.A.S., Sauter, S.L., Chosewood, L.C., Schill, A.L., Howard, J.J. (Eds.). American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Schill, A.L.; Chosewood, L.C. The NIOSH Total Worker Health™ program: An overview. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2013, 55, S8-S11.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph17197154