Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) stands out among endogenous lipid mediators for its neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic functions. PEA belonging to the N-acetylanolamine class of phospholipids was first isolated from soy lecithin, egg yolk, and peanut flour. It is currently used for the treatment of different types of neuropathic pain, such as fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and many other conditions.

- PEA

- ALIAmides

- neuroinflammation

1. PEA, an Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Substance

Lipid molecules may play a primary role essential to fight, or at least delay, chronic neuroinflammation, a phenomenon underlying many neurodegenerative diseases. A class of anti-inflammatory molecules are the Autacoid Local Injury Antagonist (ALIA) amides [1]. This acronym, coined by the research group of Rita Levi Montalcini, describes a group of endogenous bioactive acyl ethanolamides with anti-inflammatory properties [2], generally referred to as N-acylethanolamines (NAEs). NAEs include PEA, an anti-inflammatory and analgesic substance, oleoylethanolamide (OEA), an anorectic substance, and anandamide (AEA), an endocannabinoid (eCB) substance with autocrine and paracrine signaling properties [3]. PEA cannot strictly be considered a classic eCB, because it has a low affinity for the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 [4][5]. However, the presence of PEA enhances the AEA activity, likely through an “entourage effect”. PEA is endowed with important anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and analgesic actions, and some of its effects are mediated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α. PEA anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective functions have been attributed in particular to eCBs belonging to the acyl ethanolamide family, as well as to their congeners, since their production is significantly increased in the sites of neuronal damage [6]. PEA is naturally found in some foods, such as egg yolk, peanut flour, soybean oil, and corn [1][7]. In animal cells, PEA is synthesized from palmitic acid, the most common fatty acid present in many foods including palm oil, meats, cheeses, butter, and other dairy products [8]. Because of its high safety and tolerability [9][10][11][12], PEA is often used as an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective mediator in the treatment of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases, alone or combined with antioxidant or analgesic molecules acting on molecular targets of central and peripheral nervous system and immune cells [11][13][14]. In the brain, PEA is produced “on demand” by neurons, microglia, and astrocytes, and thus plays a pleiotropic and pro-homeostatic role, when faced with external stressors provoking inflammation. PEA exerts a local anti-injury function by down-modulating mast cell activation and protecting neurons from excitotoxicity [15][16][17]. The synthesis of PEA takes place in the membranes of various cell populations and mainly involves the class of N-acylphosphatidylethanolamines (NAPEs). Similar to its eCB congeners, PEA acts as local neuroprotective mediator and its physiological tone depends on the finely regulated balance between biosynthesis (mainly catalyzed by NAPE-selective phospholipase D) and degradation (mainly catalyzed by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase) [18][19][20].

It was proposed that PEA exerts its effects through three mechanisms, which are not mutually exclusive. The first mechanism advances that PEA acts by down-regulating mast-cell degranulation, via an ALIA effect [21][22][23]; the second one, the entourage effect, postulates that PEA acts by enhancing the anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive effects exerted by AEA [4][24][25]; and finally, the third one, the “receptor mechanism”, is based on PEA’s capability to directly stimulate either PPAR-α or the orphan receptor G-protein coupling, GPR55, which mediates many anti-inflammatory effects [26][27].

PEA lacks a direct antioxidant capacity to prevent the formation of free radicals and counteract the damage of DNA, lipids, and proteins [1]. With its lipid structure and the large size of heterogeneous particles in the naïve state, PEA has limitations in terms of solubility and bioavailability. To overcome these problems, PEA has been micronized (m-PEA) or ultra-micronized (um-PEA) [28]. Several in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies attest that PEA, especially in its micrometer-sized crystalline forms, may be a therapeutic agent for the effective treatment of neuroinflammatory pathologies [29]. m-PEA and um-PEA show enhanced rate of dissolution and absorption [30], better bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy when compared to its naïve form [31][32]. Since, as already mentioned, PEA has no antioxidant effects per se, the combination of PEA’s ultra-micronized forms with an antioxidant agent, such as a flavonoid, results in more efficacious forms than either molecule alone, potentiating the pharmacological effects of both compounds [33]. In fact, among the natural molecules with excellent antioxidant and antimicrobial functions there are flavonoids, as firstly luteolin, and also polydatin, quercetin, and silymarin. These compounds possess marked antioxidant and neuroprotective pharmacological actions, by modulating apoptosis and release of cytokines and free radicals (reactive oxygen and nitrogen species), suppressing the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha, inhibiting autophagy, and controlling signal transduction pathways [1][34]. In particular, luteolin is able to improve the PEA morphology: while naïve PEA has a morphology featured by large flat crystals, very small quantities of luteolin stabilize the microparticles by inhibiting the PEA crystallization process [35]. The combination of PEA and luteolin makes co-um-PEALut a product able to tackle several neuroinflammatory conditions, and to have protective effects [33].

2. PEA Action in the Presence of Aging and Neurodegeneration

Aging is the result of a continuous interaction between biological mechanisms and environmental factors, such as life events, health conditions, and lifestyle habits. Although aging is not necessarily synonymous with disease, the deterioration in cell function that increases with advancing age progressively increments the risk of developing disease and disability, because bodily and brain cellular responses become less and less efficient [36]. Namely, aging is characterized by gradual and permanent accumulation of cellular and molecular damage (such as abnormal protein dynamics, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, oxidative stress, neurotrophin dysfunction), progressive structural changes of neurons (deregulation of neurotransmitters and neuro-signals), loss of tissue and organ function, and neuroinflammatory processes [37][38][39]. Unlike the normally beneficial acute inflammatory response, chronic neuroinflammation can lead to damage and destruction of tissues, and often results from inappropriate immune responses [40]. A fundamental principle behind neuroinflammation is the existence of numerous signaling pathways between glial cells and immune system. Notably, despite different triggering events, a common feature of several central and peripheral neuropathologies is chronic immune activation, particularly of the microglia, the resident macrophages of the central nervous system [41]. Individual neurodegenerative disorders are heterogeneous in etiopathogenesis and symptomatology, but biomedical research has revealed many similarities among them at the subcellular level. These similarities suggest that therapeutic advances against one neurodegenerative disease might ameliorate other diseases as well [42].

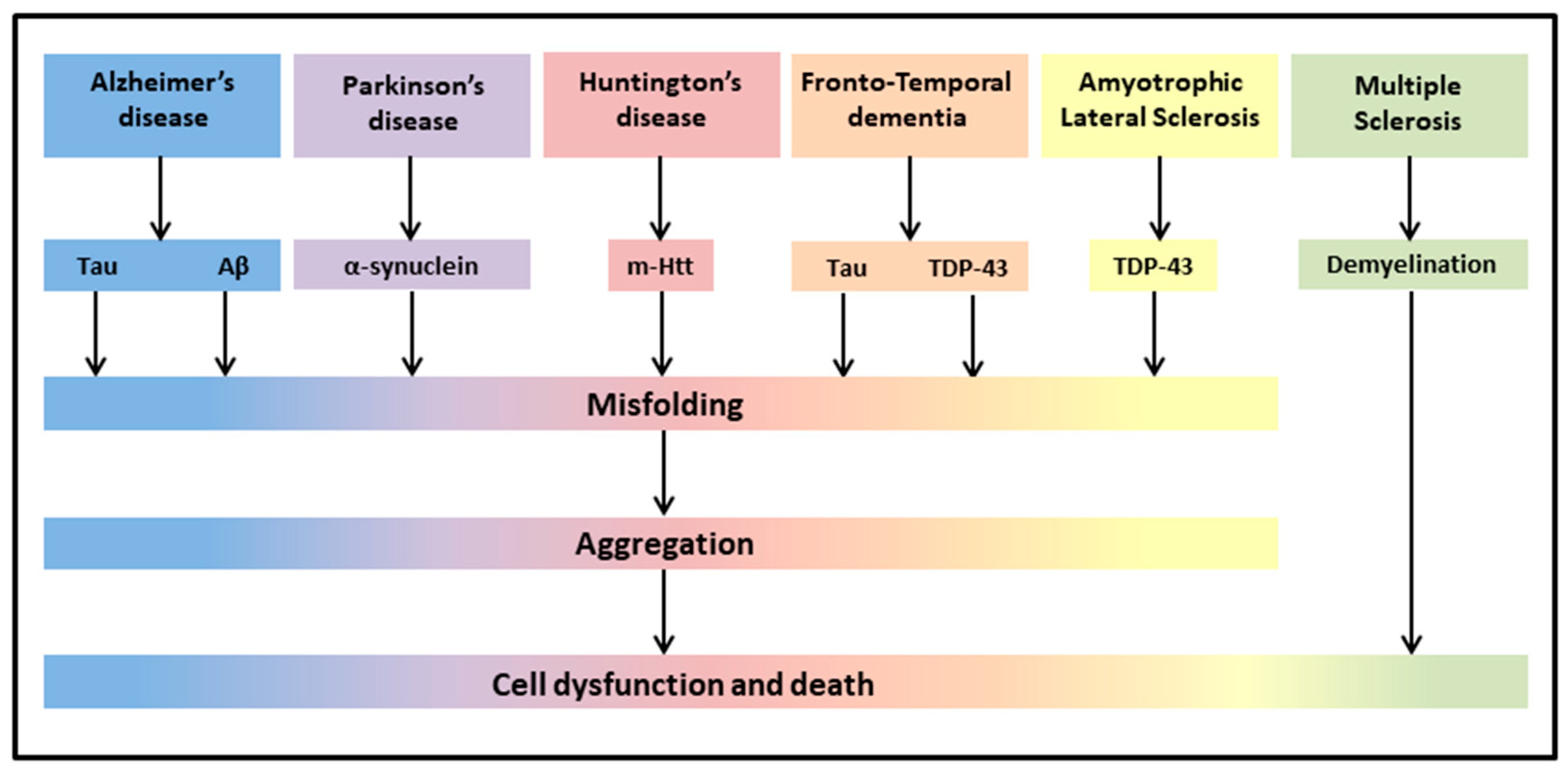

The most common neurodegenerative diseases encompass a wide range of conditions which impair mobility, muscle coordination and strength, mood, and cognition. They are amyloidosis, tauopathies, α-synucleinopathies, proteopathies (TAR DNA-binding protein 43, TDP-43), and include Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Huntington’s Disease (HD), Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) (Figure 1) [43].

Figure 1. Neurodegenerative diseases share common pathological hallmarks leading to cell dysfunction and death.

Up to now, the treatment of most of these neurodegenerative diseases was mainly symptomatic (dopaminergic treatment for PD, inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase for cognitive disorders, antipsychotics for dementia), despite significant attempts to find drugs reducing or rescuing the debilitating symptoms [44][45][46]. In this context, integrative treatments of these neurodegenerative diseases have been investigated through a number of in vitro and in vivo animal models of disease, and, when combined with classical drug therapies, are in the frontline of research in an attempt to protect against neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, and thereby improve symptomatology of the neurodegenerative patients [45]. Since most clinical studies on PEA are related to neuropathic pain or inflammation-related peripheral conditions, and there are fewer studies evaluating the possible beneficial effects of PEA on neurodegenerative diseases, researchers were interested to offer a general overview of the effects of PEA on different symptoms of neurodegeneration, taking into account both human (Table 1) and rodent (Table 2) studies.

Table 1. Summary of human studies using PEA in the presence of neurodegeneration.

| Study | Disease | Sample | um PEA (Alone or In Combination) |

Dosage | Duration | Main Outcomes of PEA Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [47] | MCI | 1 patient | co-um-PEALut | 700/70 mg daily | T3: 3 months treatment T9: 9 months follow-up | T3: mild (though not significant) cognitive improvement; T9: near-normal neuropsychological assessment; improvement in test scores; brain SPECT near-normal. |

| [48] | PD | 30 patients | PEA added to regular levodopa |

600 mg daily | 12 months | Progressive reduction in the total MDS-UPDRS score; reduction in most nonmotor and motor symptoms. |

| [49] | PD | 1 patient | co-um-PEALut added to regular carbidopa/levodopa | 700/70 mg daily | 4 months | Complete resolution of leg and trunk dyskinesia and marked reduction in the onset of camptocormia during the “off” state. |

| [50] | FTD | 17 patients | co-um-PEALut | 700 mg/2 daily | 4 weeks | Improvement in test scores and neurophysiological evaluation; increase in TMS-evoked frontal lobe activity and of high-frequency oscillations in the beta/gamma range. |

| [51] | ALS | 1 patient | PEA | 600 mg/2 daily | ∼40 days | Improvement in clinical picture. |

| [52] | ALS | 28 treated and 36 untreated patients |

PEA + 50 mg riluzole or 50 mg riluzole only |

600 mg/2 daily | 6 months | Lower decrease in forced vital capacity over time as compared with untreated ALS patients. |

| [53] | MS | 24 patients 17 healthy controls |

eCBs levels in blood | _ | _ | eCB system is altered in MS. |

| [54] | MS | 1 patient | PEA | 600 mg/2 daily | ∼9 months | Pain reduction; increased interval between acupuncture sessions. |

| [55] | MS | 29 patients | PEA added to IFN-β1a or placebo |

600 mg daily | 12 months | Improvement in pain sensation, no reduction of erythema at the injection site, improved evaluation of quality of life, increase in PEA, AEA and OEA plasma levels, reduction of interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-17 serum profile. |

| [56] | Myasthenia gravis | 22 patients | PEA | 600 mg/2 daily | 1 week | Reduced level of disability and decremental muscle response. |

AEA-Anandamide; ALS-Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; co-um-PEALut-combined ultra-micronized PEA/Lutein; eCB-endocannabinoid; FTD-Frontotemporal Dementia; IFN-β1-Interferon-beta-1; MCI-Mild Cognitive Impairment; MDS-UPDRS-Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; MS-Multiple Sclerosis; OEA-Oleoylethanolamide; PD-Parkinson Disease; um-ultra-micronized.

Table 2. Summary of experimental studies using PEA in the presence of neurodegeneration.

| Study | Disease | Sample | um PEA (Alone or In Combination) |

Dosage | Duration | Main Outcomes of PEA Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [57] | AD model (Aβ 1–42 intra-hippocampal injection) |

Male adult Sprague-Dawley rats (9–12/group) |

i.p. PEA PEA added to GW6471 |

PEA:10 mg/kg; GW647: 2 mg/kg |

7 days | Restoration of Aβ 1–42-induced alterations; reduced mnestic deficits. |

| [58] | AD model (Aβ 25–35 i.c.v. injection) |

Male PPAR-α/(B6.129S4-SvJaePparatm 1Gonz) and WT mice (9–10/group) |

s.c. PEA and GW7647 |

PEA: 3–30 mg/kg daily, GW7647: 5 mg/kg daily | 1–2 weeks or a single dose |

Reduction (10 mg/kg) or prevention (30 mg/kg) of behavioral impairments. No rescue of memory deficits. PEA acute treatment was ineffective. |

| [59] | AD model | 3-month-old male 3 × Tg-AD and WT mice (9–10/group) |

s.c. PEA or vehicle |

10 mg/kg daily | 90 days | Counteraction of disease progression, improvement of trophic support to neurons, in the absence of astrocytes and neuronal toxicity. |

| [60] | AD model | 3-month-old or 9-month-old male 3 × Tg-AD or WT mice (7–11/group) |

s.c. PEA or vehicle |

10 mg/kg daily | 90 days | Improvement of learning and memory, amelioration of depressive and anhedonia-like symptoms, reduced Aβ formation, tau protein phosphorylation, promotion of hippocampal neuronal survival and astrocytic function, rebalancing of glutamatergic transmission, restraint of neuroinflammation. |

| [61] | AD model | 2-month-old male 3 × Tg-AD or WT mice (7–11/group) |

oral PEA or vehicle |

single dose/sub-chronic/chronic:100 mg/kg daily | 1–8–90 days | Rescue of cognitive deficit, restraint of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, reduced increase in hippocampal glutamate levels. |

| [62] | PD model (MPTP) | 6–7-week-old male PPAR-αKO PPAR-αWT mice (10/group) |

i.p. PEA |

10 mg/kg | 8 days | Reduction of MPTP-induced microglial activation, glial fibrillary acidic protein positive expression astrocyte numbers, overexpression of S100b; protection against alterations in microtubule-associated protein 2a,b, dopamine transporter, nNOS-positive cells in the substantia nigra. Reversal of motor deficits. |

| [63] | PD model (MPTP) | 3/21-month-old male CD1 mice (10/group) |

oral PEA |

10 mg/kg | 60 days | Amelioration of behavioral deficits and of reduction of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine transporter in substantia nigra. Reduction of hippocampal proinflammatory cytokines and pro-neurogenic effects. |

| [64] | PD model (6-OHDA) |

Ten-week-old male Swiss CD1 mice (6 × group) | s.c. PEA or GW7647 |

PEA 3–30 mg/kg/day; GW7647 5 mg/kg/day |

28 days | Improvement of behavioral impairment. Increased tyrosine hydroxylase expression at striatal level. Reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory enzymes, protective scavenging effect. |

| [65] | PD model (MPTP) | 8-week-old male C57BL/6 (10/group) | i.p. co-um-PEALut |

1 mg/kg daily | 8 days | Reduction of motor impairment, cataleptic response, immobility and anxiety levels. Reduction of neuronal degeneration and of specific PD markers, attenuation of inflammatory processes (activation of astrocytes, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and nitric oxide synthase), stimulation of autophagy. |

| [66] | PD model (MPTP) |

8-week-old male C57BL/6 (10/group) |

oral PEA-OXA or vehicle |

10 mg/kg daily | 8 days | Prevention of MPTP-induced bradykinesia and anxiety, and neuronal degeneration of the dopaminergic tract, prevention of dopamine depletion, modulation of microglia and astrocyte activation. |

| [67] | HD model | ∼32-day-old-R6/2 10-week-old R6/2 mice and WT mice (4/group) |

Measurement of PEA, AEA and 2-AG endogenous levels |

_ | _ | Alteration of the eCB system, decreased levels of PEA in the striatum |

| [68] | MS model (EAE) | 12-week-old female C57BL/6 (8/group) |

i.p. PEA or CBD or in combination |

PEA 5 mg/kg CBD 5 mg/kg |

3 days | Reduced severity of EAE neurobehavioral scores, diminished inflammation, demyelination, axonal damage and inflammatory cytokine expression. |

| [69] | MS model (chronic relapsing EAE) | Biozzi ADH mice (>6/group) |

i.v. or i.p. PEA |

1–10 mg/kg | Single injection |

Amelioration of spasticity |

| [70] | MS model (EAE) | C57BL/6 mice (8/group) |

i.p. co-um-PEALut or vehicle |

0.1, 1, and 5 mg/kg | 16 days | Dose-dependent improvement of clinical signs through anti-inflammatory signals and pro-resolving circuits. |

| [71] | MS model (TMEV-IDD) | Four-week female SJL/J mice |

i.p. PEA or vehicle |

5 mg/kg | 10 days | Reduction of motor disability, anti-inflammatory effect. |

| [72] | Vascular dementia |

CD1 mice | Oral PEA-OXA or vehicle |

10 mg/kg daily | 15 days | Improvement of behavioral deficits, reduction of histological alterations, decrease of markers of astrocyte and microglia activation and oxidative stress, modulation of antioxidant response, inhibition of apoptotic process. |

2-AG-2-Arachidonoylglycerol; 6-OHDA-6-hydroxydopamine; Aβ-amyloid beta; CBD-cannabidiol; EAE-Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis; i.c.v.-intracerebroventricular; i.p.-intraperitoneal; KO-knockout; MPTP-1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; nNOS-neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase; PEA-OXA-2-pentadecyl-2-oxazoline; PPAR-α-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α; s.c.-subcutaneous; TMEV-IDD-Theiler’s Murine Encephalomyelitis Virus-Induced Demyelinating Disease; WT-Wild Type.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12050667

References

- Peritore, A.F.; Siracusa, R.; Crupi, R.; Cuzzocrea, S. Therapeutic Efficacy of Palmitoylethanolamide and Its New Formulations in Synergy with Different Antioxidant Molecules Present in Diets. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2175.

- Chiurchiù, V.; Leuti, A.; Smoum, R.; Mechoulam, R.; Maccarrone, M. Bioactive lipids ALIAmides differentially modulate inflammatory responses of distinct subsets of primary human T lymphocytes. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2018, 32, 5716–5723.

- Rahman, I.A.; Tsuboi, K.; Uyama, T.; Ueda, N. New players in the fatty acyl ethanolamide metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 86, 1–10.

- Ho, W.S.; Barrett, D.A.; Randall, M.D. ‘Entourage’ effects of N-palmitoylethanolamide and N-oleoylethanolamide on vasorelaxation to anandamide occur through TRPV1 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155, 837–846.

- Musella, A.; Fresegna, D.; Rizzo, F.R.; Gentile, A.; Bullitta, S.; De Vito, F.; Guadalupi, L.; Centonze, D.; Mandolesi, G. A novel crosstalk within the endocannabinoid system controls GABA transmission in the striatum. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7363.

- Costa, B.; Conti, S.; Giagnoni, G.; Colleoni, M. Therapeutic effect of the endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitoylethanolamide, in rat acute inflammation: Inhibition of nitric oxide and cyclo–oxygenase systems. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 137, 413–420.

- Carta, G.; Murru, E.; Banni, S.; Manca, C. Palmitic Acid: Physiological Role, Metabolism and Nutritional Implications. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 902.

- Keppel Hesselink, J.M.; de Boer, T.; Witkamp, R.F. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Natural Body–Own Anti–Inflammatory Agent, Effective and Safe against Influenza and Common Cold. Int. J. Inflam. 2013, 2013, 151028.

- Nestmann, E.R. Safety of micronized palmitoylethanolamide (microPEA): Lack of toxicity and genotoxic potential. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 5, 292–309.

- Gabrielsson, L.; Mattsson, S.; Fowler, C.J. Palmitoylethanolamide for the treatment of pain: Pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 932–942.

- Petrosino, S.; Di Marzo, V. The pharmacology of palmitoylethanolamide and first data on the therapeutic efficacy of some of its new formulations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1349–1365.

- Petrosino, S.; Schiano Moriello, A. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Nutritional Approach to Keep Neuroinflammation within Physiological Boundaries–A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9526.

- Petrosino, S.; Cristino, L.; Karsak, M.; Gaffal, E.; Ueda, N.; Tüting, T.; Bisogno, T.; De Filippis, D.; D’Amico, A.; Saturnino, C.; et al. Protective role of palmitoylethanolamide in contact allergic dermatitis. Allergy 2010, 65, 698–711.

- Tsuboi, K.; Uyama, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Ueda, N. Endocannabinoids and related N-acylethanolamines: Biological activities and metabolism. Inflamm. Regener. 2018, 38, 28.

- Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Palmitoylethanolamide is a new possible pharmacological treatment for the inflammation associated with trauma. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 237–255.

- Mattace Raso, G.; Russo, R.; Calignano, A.; Meli, R. Palmitoylethanolamide in CNS health and disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 86, 32–41.

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Zusso, M.; Giusti, P. An Inflammation–Centric View of Neurological Disease: Beyond the Neuron. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 72.

- Solorzano, C.; Zhu, C.; Battista, N.; Astarita, G.; Lodola, A.; Rivara, S.; Mor, M.; Russo, R.; Maccarrone, M.; Antonietti, F.; et al. Selective N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase inhibition reveals a key role for endogenous palmitoylethanolamide in inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20966–20971.

- Tsuboi, K.; Ikematsu, N.; Uyama, T.; Deutsch, D.G.; Tokumura, A.; Ueda, N. Biosynthetic pathways of bioactive N–acylethanolamines in brain. CNS Neurol. Disord. 2013, 12, 7–16.

- Rankin, L.; Fowler, C.J. The Basal Pharmacology of Palmitoylethanolamide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7942.

- Aloe, L.; Leon, A.; Levi-Montalcini, R. A proposed autacoid mechanism controlling mastocyte behaviour. Agents Actions 1993, 39, C145–C147.

- Paladini, A.; Varrassi, G.; Bentivegna, G.; Carletti, S.; Piroli, A.; Coaccioli, S. Palmitoylethanolamide in the Treatment of Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Pain Res. Treat. 2017, 2017, 1486010.

- Roviezzo, F.; Rossi, A.; Caiazzo, E.; Orlando, P.; Riemma, M.A.; Iacono, V.M.; Guarino, A.; Ialenti, A.; Cicala, C.; Peritore, A.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide Supplementation during Sensitization Prevents Airway Allergic Symptoms in the Mouse. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 857.

- Conti, S.; Costa, B.; Colleoni, M.; Parolaro, D.; Giagnoni, G. Antiinflammatory action of endocannabinoid palmitoylethanolamide and the synthetic cannabinoid nabilone in a model of acute inflammation in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 181–187.

- Saturnino, C.; Popolo, A.; Ramunno, A.; Adesso, S.; Pecoraro, M.; Plutino, M.R.; Rizzato, S.; Albinati, A.; Marzocco, S.; Sala, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant and Crystallographic Studies of N-Palmitoyl-ethanol Amine (PEA) Derivatives. Molecules 2017, 22, 616.

- Warden, A.; Truitt, J.; Merriman, M.; Ponomareva, O.; Jameson, K.; Ferguson, L.B.; Mayfield, R.D.; Harris, R.A. Localization of PPAR isotypes in the adult mouse and human brain. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27618.

- Shi, Q.X.; Yang, L.K.; Shi, W.L.; Wang, L.; Zhou, S.M.; Guan, S.Y.; Zhao, M.G.; Yang, Q. The novel cannabinoid receptor GPR55 mediates anxiolytic-like effects in the medial orbital cortex of mice with acute stress. Mol. Brain 2017, 10, 38.

- D’Amico, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Di Paola, R. ALIAmides Update: Palmitoylethanolamide and Its Formulations on Management of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5330.

- Beggiato, S.; Tomasini, M.C.; Ferraro, L. Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 821.

- Ardizzone, A.; Fusco, R.; Casili, G.; Lanza, M.; Impellizzeri, D.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Effect of Ultra-Micronized-Palmitoylethanolamide and Acetyl-l-Carnitine on Experimental Model of Inflammatory Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1967.

- Impellizzeri, D.; Bruschetta, G.; Cordaro, M.; Crupi, R.; Siracusa, R.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Micronized/ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide displays superior oral efficacy compared to nonmicronized palmitoylethanolamide in a rat model of inflammatory pain. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 136.

- Noce, A.; Albanese, M.; Marrone, G.; Di Lauro, M.; Pietroboni Zaitseva, A.; Palazzetti, D.; Guerriero, C.; Paolino, A.; Pizzenti, G.; Di Daniele, F.; et al. Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide (um-PEA): A New Possible Adjuvant Treatment in COVID-19 patients. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 336.

- Cordaro, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Crupi, R. An Update of Palmitoylethanolamide and Luteolin Effects in Preclinical and Clinical Studies of Neuroinflammatory Events. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 216.

- Ashaari, Z.; Hadjzadeh, M.A.; Hassanzadeh, G.; Alizamir, T.; Yousefi, B.; Keshavarzi, Z.; Mokhtari, T. The flavone luteolin improves central nervous system disorders by different mechanisms: A review. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 65, 491–506.

- Adami, R.; Liparoti, S.; Di Capua, A.; Scogliamiglio, M.; Reverchon, E. Production of PEA composite microparticles with polyvinylpyrrolidone and luteolin using supercritical assisted atomization. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2019, 143, 82–89.

- Power, R.; Prado-Cabrero, A.; Mulcahy, R.; Howard, A.; Nolan, J.M. The Role of Nutrition for the Aging Population: Implications for Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 619–639.

- Vauzour, D.; Camprubi-Robles, M.; Miquel-Kergoat, S.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Bánáti, D.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Bowman, G.L.; Caberlotto, L.; Clarke, R.; Hogervorst, E.; et al. Nutrition for the ageing brain: Towards evidence for an optimal diet. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 35, 222–240.

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42.

- Azam, S.; Haque, M.E.; Balakrishnan, R.; Kim, I.S.; Choi, D.K. The Ageing Brain: Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 683459.

- Skaper, S.D.; Barbierato, M.; Facci, L.; Borri, M.; Contarini, G.; Zusso, M.; Giusti, P. Co–Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide/Luteolin Facilitates the Development of Differentiating and Undifferentiated Rat Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 103–114.

- Jakel, S.; Dimou, L. Glial Cells and Their Function in the Adult Brain: A Journey through the History of Their Ablation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 24.

- Hussain, R.; Zubair, H.; Pursell, S.; Shahab, M. Neurodegenerative Diseases: Regenerative Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 177.

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028035.

- Desai, A.K.; Grossberg, G.T. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2005, 64, S34–S39.

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Schapira, A.H.V. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 464–474.

- Rees, K.; Stowe, R.; Patel, S.; Ives, N.; Breen, K.; Clarke, C.E.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as disease-modifying agents for Parkinson’s disease: Evidence from observational studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, Cd008454.

- Calabrò, R.S.; Naro, A.; De Luca, R.; Leonardi, S.; Russo, M.; Marra, A.; Bramanti, P. PEALut efficacy in mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from a SPECT case study! Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 1279–1282.

- Brotini, S.; Schievano, C.; Guidi, L. Ultra–micronized Palmitoylethanolamide: An Efficacious Adjuvant Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2017, 16, 705–713.

- Brotini, S. Palmitoylethanolamide/Luteolin as Adjuvant Therapy to Improve an Unusual Case of Camptocormia in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Report. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 18, 12–14.

- Assogna, M.; Casula, E.P.; Borghi, I.; Bonnì, S.; Samà, D.; Motta, C.; Di Lorenzo, F.; D’Acunto, A.; Porrazzini, F.; Minei, M.; et al. Effects of Palmitoylethanolamide Combined with Luteoline on Frontal Lobe Functions, High Frequency Oscillations, and GABAergic Transmission in Patients with Frontotemporal Dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 76, 1297–1308.

- Clemente, S. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis treatment with ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide: A case report. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2012, 11, 933–936.

- Palma, E.; Reyes–Ruiz, J.M.; Lopergolo, D.; Roseti, C.; Bertollini, C.; Ruffolo, G.; Cifelli, P.; Onesti, E.; Limatola, C.; Miledi, R.; et al. Acetylcholine receptors from human muscle as pharmacological targets for ALS therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016, 113, 3060–3065.

- Jean-Gilles, L.; Feng, S.; Tench, C.R.; Chapman, V.; Kendall, D.A.; Barrett, D.A.; Constantinescu, C.S. Plasma endocannabinoid levels in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 287, 212–215.

- Kopsky, D.J.; Hesselink, J.M. Multimodal stepped care approach with acupuncture and PPAR–α agonist palmitoylethanolamide in the treatment of a patient with multiple sclerosis and central neuropathic pain. Acupunct. Med. 2012, 30, 53–55.

- Orefice, N.S.; Alhouayek, M.; Carotenuto, A.; Montella, S.; Barbato, F.; Comelli, A.; Calignano, A.; Muccioli, G.G.; Orefice, G. Oral Palmitoylethanolamide Treatment Is Associated with Reduced Cutaneous Adverse Effects of Interferon–β1a and Circulating Proinflammatory Cytokines in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 2016, 13, 428–438.

- Onesti, E.; Frasca, V.; Ceccanti, M.; Tartaglia, G.; Gori, M.C.; Cambieri, C.; Libonati, L.; Palma, E.; Inghilleri, M. Short–Term Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide Therapy in Patients with Myasthenia Gravis: A Pilot Study to Possible Future Implications of Treatment. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2019, 18, 232–238.

- Scuderi, C.; Stecca, C.; Valenza, M.; Ratano, P.; Bronzuoli, M.R.; Bartoli, S.; Steardo, L.; Pompili, E.; Fumagalli, L.; Campolongo, P.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide controls reactive gliosis and exerts neuroprotective functions in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1419.

- D’Agostino, G.; Russo, R.; Avagliano, C.; Cristiano, C.; Meli, R.; Calignano, A. Palmitoylethanolamide protects against the amyloid–β25–35–induced learning and memory impairment in mice, an experimental model of Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 37, 1784–1792.

- Bronzuoli, M.R.; Facchinetti, R.; Steardo, L., Jr.; Romano, A.; Stecca, C.; Passarella, S.; Steardo, L.; Cassano, T.; Scuderi, C. Palmitoylethanolamide Dampens Reactive Astrogliosis and Improves Neuronal Trophic Support in a Triple Transgenic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: In vitro and In vivo Evidence. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4720532.

- Scuderi, C.; Bronzuoli, M.R.; Facchinetti, R.; Pace, L.; Ferraro, L.; Broad, K.D.; Serviddio, G.; Bellanti, F.; Palombelli, G.; Carpinelli, G.; et al. Ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide rescues learning and memory impairments in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by exerting anti–inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 32.

- Beggiato, S.; Tomasini, M.C.; Cassano, T.; Ferraro, L. Chronic Oral Palmitoylethanolamide Administration Rescues Cognitive Deficit and Reduces Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Glutamate Levels in A Transgenic Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 428.

- Esposito, E.; Impellizzeri, D.; Mazzon, E.; Paterniti, I.; Cuzzocrea, S. Neuroprotective activity of palmitoylethanolamide in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41880.

- Crupi, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Casili, G.; Evangelista, M.; Cuzzocrea, S. N–palmitoylethanolamide prevents parkinsonian phenotypes in aged mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 8455–8472.

- Avagliano, C.; Russo, R.; De Caro, C.; Cristiano, C.; La Rana, G.; Piegari, G.; Paciello, O.; Citraro, R.; Russo, E.; De Sarro, G.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide protects mice against 6–OHDA–induced neurotoxicity and endoplasmic reticulum stress: In vivo and in vitro evidence. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 113 Pt A, 276–289.

- Siracusa, R.; Paterniti, I.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Crupi, R.; Navarra, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Esposito, E. The Association of Palmitoylethanolamide with Luteolin Decreases Neuroinflammation and Stimulates Autophagy in Parkinson’s Disease Model. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 1350–1365.

- Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Crupi, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Peritore, A.F.; D’Amico, R.; Gugliandolo, E.; Di Paola, R.; Cuzzocrea, S. 2–Pentadecyl–2–Oxazoline Reduces Neuroinflammatory Environment in the MPTP Model of Parkinson Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 9251–9266.

- Bisogno, T.; Martire, A.; Petrosino, S.; Popoli, P.; Di Marzo, V. Symptom-related changes of endocannabinoid and palmitoylethanolamide levels in brain areas of R6/2 mice, a transgenic model of Huntington’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52, 307–313.

- Baker, D.; Pryce, G.; Croxford, J.L.; Brown, P.; Pertwee, R.G.; Makriyannis, A.; Khanolkar, A.; Layward, L.; Fezza, F.; Bisogno, T.; et al. Endocannabinoids control spasticity in a multiple sclerosis model. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 300–302.

- Rahimi, A.; Faizi, M.; Talebi, F.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Kahrizi, F.; Naderi, N. Interaction between the protective effects of cannabidiol and palmitoylethanolamide in experimental model of multiple sclerosis in C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci. 2015, 290, 279–287.

- Contarini, G.; Franceschini, D.; Facci, L.; Barbierato, M.; Giusti, P.; Zusso, M. A co–ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide/luteolin composite mitigates clinical score and disease–relevant molecular markers in a mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 126.

- Loría, F.; Petrosino, S.; Mestre, L.; Spagnolo, A.; Correa, F.; Hernangómez, M.; Guaza, C.; Di Marzo, V.; Docagne, F. Study of the regulation of the endocannabinoid system in a virus model of multiple sclerosis reveals a therapeutic effect of palmitoylethanolamide. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 633–641.

- Impellizzeri, D.; Siracusa, R.; Cordaro, M.; Crupi, R.; Peritore, A.F.; Gugliandolo, E.; D’Amico, R.; Petrosino, S.; Evangelista, M.; Di Paola, R.; et al. N–Palmitoylethanolamine–oxazoline (PEA–OXA): A new therapeutic strategy to reduce neuroinflammation, oxidative stress associated to vascular dementia in an experimental model of repeated bilateral common carotid arteries occlusion. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 125, 77–91.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!