Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The basis of the MedDi model is the diet of the people of the island of Crete in the early 1950s; it is characterized by a high plant/animal food ratio, and, compared with other populations, it is linked with a markedly low prevalence of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, asthma, erectile dysfunction, depression and cognitive decline, and with a high life expectancy.

- Mediterranean diet

- asthma

- atopy

- antioxidants

- lipids

- vitamin

1. Introduction

The prevalence of atopy and asthma has increased substantially in most developed countries [1][2][3], a trend potentially influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [4]. While our genetic profile is unlikely to have altered much in the last decades, our living conditions and habits have undergone major changes [5]. Environmental exposures are, therefore, considered to be the key culprit for the escalation [6]. As environmental factors may be amenable to intervention, their identification is important in efforts to curtail the current allergy epidemic. The observation that the rate of asthma has risen concomitantly with the degree of affluence [7] has kindled a search for specific cultural influences. It has been documented that culture shapes the asthma experience, its diagnosis and management, relevant research, and the politics determining funding [8].

As initially proposed by Burney [9] and later supported and extended by Seaton [10], changes in dietary habits could be partly responsible for the observed increase in atopic disease [11]. The rise in the prevalence of asthma in Western societies has coincided with marked modifications in the diet of these populations, leading to theories of a link between nutritional factors and asthma/atopy [12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. Among other factors, a link between a diet high in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and AGE-forming sugars and an increase in food allergy was proposed by Smith and colleagues [2]. It is thought that AGEs might function as a “false alarm” for the immune system against food antigens. In the pathogenesis of asthma/allergic airway inflammation, a receptor specific for the AGEs (RAGE) appears to be a critical participant [19].

A trend towards a lower prevalence of asthma in the Mediterranean region was identified in 1998 by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) [20], and epidemiological evidence has indicated that the Mediterranean diet (MedDi) might be protective against asthma [21][22][23][24].

Hence, a reasonable hypothesis is that adherence to the MedDi may modulate asthma pathogenesis, but even with a substantial body of research evidence, findings on such an association are far from conclusive. To account for the discrepant results, a variety of limitations, cultural, geographical, biological and methodological, must be taken into consideration. In this entry, researchers present and discuss the currently available evidence on the relationship of the MedDi with asthma/atopy, researchers underscore the research pitfalls, and researchers propose ways forward, including possible interventions. Researchers have opted to focus on the “contemporary Greek MedDi”, rather than the general archetype of the “Mediterranean diet of the previous century”, in an effort to circumvent one of the key research limitations, which is the diversity of the MedDi.

2. Obstacles to the Validation of Associations

2.1. Issue No. 1: What Is a “Mediterranean Diet”?

The basis of the MedDi model is the diet of the people of the island of Crete in the early 1950s [25]; it is characterized by a high plant/animal food ratio, and, compared with other populations, it is linked with a markedly low prevalence of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, asthma, erectile dysfunction, depression and cognitive decline, and with a high life expectancy [26].

The typical MedDi pattern is composed of the following [25][27][28]: (1) daily consumption of refined cereals, and their products (bread, pasta, etc.), fruit (4–6 servings/day), vegetables (2–3 servings/day), olive oil (as the principal source of fat), wine (1–2 glasses/day) and dairy products (1–2 servings/day); (2) weekly consumption of fish, legumes, poultry, olives and nuts (4–6 servings/week), and (3) monthly consumption of red meat and meat products (4–5 servings/month). In sum, the MedDi is characterized by a high intake of plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes, olive oil and nuts, a high to moderate intake of fish and seafood, a moderate to low intake of dairy products and wine, and only small quantities of red meat.

MedDi is, by most accounts, a generalization, if not a misnomer, as several variations are observed around the Mediterranean basin [29], which, unsurprisingly, reflects the diversity in religious, economic and social structures in these areas. For example, Muslims abstain from pork and wine, while Greek Orthodox populations usually avoid eating meat on Wednesdays and Fridays and during the 40-day fasting periods before major religious festivals. Differences stem also from the local availability of foodstuffs, which was a critical issue until some decades ago, as food transfer was arduous, and people had to rely on what they could produce and procure locally. In the 1960s, therefore, even different regions within the same Mediterranean country followed their own, distinct, dietary patterns [30].

Food transport is no longer a factor, but regional production continues to dictate, to some extent, the local cuisine. In parallel, food consumption patterns have changed during the last 50 years in most regions, including Crete [31], with adaptation to Westernized dietary patterns, leading to a poor MedDi quality index [32][33][34]. The cardinal feature of a Mediterranean-type diet, olive oil, however, still serves as the principal source of dietary fat in Crete, as in many Mediterranean regions, providing the precious monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyphenols [35][36].

2.2. Issue No. 2: Nutrients, Foods or Dietary Patterns?

Diet is a highly complex exposure variable. Traditional research approaches, focusing on individual nutrients, generate methodological pitfalls, as they may fail to take into account important nutrient interactions [37][38]. Perceived “healthy” foods contain numerous beneficial nutrients, necessitating stringent analytical adjustment to uncover their individual actions [39], but this approach would require sample sizes in excess of those reported in most published studies [40][41]. There are also conceptual issues; humans consume concurrently a variety of foods containing a constellation of nutrients, and the clinical relevance of the presumed effects of single nutrients is, therefore, questionable. It is reasonable to assume that any beneficial clinical effect is mediated through the combined action of several dietary agents [42][43], and the implication is that large-scale dietary manipulation, rather than single nutrient supplementation, would be a more promising approach for asthma-related research and possible disease prevention. In practice, the investigation of dietary patterns, rather than individual nutrients, is a paradigm that is gaining momentum [44]. To that end, the use of diet scores has been recommended, and various different MedDi scores have been constructed and used in research, including the Mediterranean diet score (MDS),the Mediterranean diet scale (MDScale) and the Mediterranean food pattern (MFP) [28][45][46]. All these indices show satisfactory performance in assessing adherence to the MedDi [47], and the MDScale and MedDi show correlation with olive oil and fiber constituents, while the MDScale shows correlation with waist-to-hip ratio and total energy intake [35].

It is of note that individual foods and constituents within the MedDi, specifically fish and olive oil appear to be particularly beneficial for asthma outcomes [48][49][50].

2.3. Issue No. 3: Observation versus Intervention

Findings on a possible correlation between diet and asthma are conflicting, but it appears that most of this disparity derives from a single methodological feature, namely, whether the studies are observational or interventional. A consistent theme in the epidemiological/cross-sectional literature is that of a beneficial effect of several dietary agents on asthma/atopy; this is in contrast with randomized clinical trials/supplementation studies, which yield inconclusive results. Several theories have been proposed to explain this discrepancy, such as the short duration of supplementation, or the requirement of an underlying deficiency for supplementation of the nutrient to show effects [51], both of which have been partly overthrown [12].

It has been suggested that positive observational evidence may stem from prenatal maternal nutrition, which could define the asthma risk of the offspring, and also serve as a model for the dietary habits of the child/grown adult [52][53]. In effect, observational studies could erroneously link the diet of the child/adult with favorable effects, when the defining factor may, in fact, be the maternal diet during pregnancy; this would also explain the failure of postnatal interventions. Although this theory has not been confirmed, it is plausible that the maternal prenatal diet may modify the future asthma risk of the child via epigenetic “programming” of the fetal lung and immune system [54]. Interest in the role of modifiable nutritional factors specific to both the prenatal and the early postnatal life is increasing, as during this time the immune system is particularly vulnerable to exogenous influences. A variety of perinatal dietary factors, including maternal diet during pregnancy, duration of breastfeeding, use of special milk formulas, timing of the introduction of complementary foods, and prenatal and early life supplementation with vitamins and probiotics/prebiotics, have all been addressed as potential targets for the prevention of asthma [55].

Breastfeeding is a sensitive period, and knowledge of its effects has, to date, been gained observationally [56][57][58]. The results related to the possible protection gained through breastfeeding against allergies and asthma have been inconsistent [59][60]. Current evidence suggests a protective role of exclusive breastfeeding in atopic dermatitis (AD), related to atopic heredity [61].

Reduced intake of omega 3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) may be a contributing factor to the increasing prevalence of wheezing disorders [62][63], and a higher ratio of n-6/n-3 PUFAs in the maternal diet, and maternal asthma, increase the risk of wheeze/asthma in the offspring [63]. The effect of n-3 PUFA supplementation in pregnant women on the risk of persistent wheeze and asthma in their offspring has been assessed. Supplementation with n-3 long-chain (LC)PUFA in the third trimester of pregnancy was shown to reduce the absolute risk of persistent wheeze and lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in infancy [64][65], and the risk of asthma by the age of 5 years [66], and later in life [67].

3. Evaluation of Dietary Constituents

Two major research hypotheses have been proposed to explain the link between dietary constituents and asthma: the lipid hypothesis and the antioxidant hypothesis. Both hypotheses are based on foods that are hallmarks of the MedDi. A third one, the anti-inflammatory hypothesis emerges to merge and corroborate the other two.

3.1. The Lipid Hypothesis

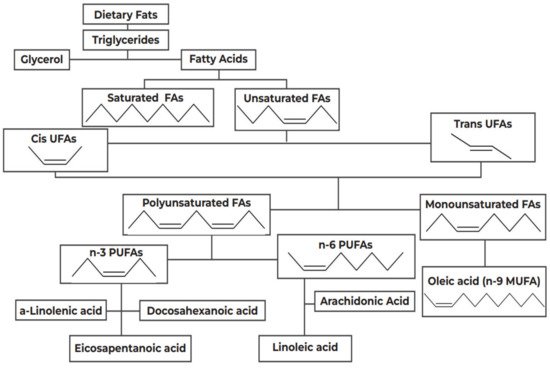

In 1997, Black and Sharpe [68] originally suggested that changes in the intake of fatty acids (FAs), in both type and quantity, has contributed to the rise of asthma and atopy in the West. FAs are categorized as saturated or unsaturated, depending on the presence of double carbon bonds, as shown in Figure 1. Unsaturated FAs are classified into MUFAs, such as oleic acid, and PUFAs, which are further divided into subgroups, the n-6 and the n-3 PUFAs, based on the position of the double carbon bonds.

Figure 1. Categorization of dietary fats. FA: Fatty Acids; PUFAs: Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids; MUFA: Monounsaturated Fatty Acids.

The n-6 PUFAs have proinflammatory properties [69]; for example, linoleic acid (LA), which is a common n-6 PUFA and the principal FA in the US diet [70], is converted into arachidonic acid (ARA), which is further metabolized by cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase into 2-series prostanoids and 4-series leukotrienes [71]. The proinflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of these agents, their promotion of a Th2 phenotype, and their association with bronchoconstriction, are well established [72][73]. A causal link between increased intake of n-6PUFAs and a high incidence of allergic disease has been suggested, which is supported by biologically plausible mechanisms, related to the role of eicosanoid mediators produced from the n-6 PUFA ARA [74]. Conversely, the n-3PUFAs, exemplified by a linolenic acid (ALA), exert an anti-inflammatory action by restricting the metabolism of ARA [75].

As shown in Figure 1, this proposed beneficial effect of the ALA catabolism products, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, n-3) stems from the competitive inhibition of LA(n-6) catabolism; EPA and DHA, naturally occurring in fish oil [76], also downregulate COX-2 gene expression and activity and suppress neutrophil function [77].

It was therefore postulated that the rising prevalence of atopy in affluent societies was preceded by reduced consumption of oily fish, which contain n-3 PUFAs, and increased intake of margarine and vegetable oils rich in n-6 PUFAs, which were favored by public health measures aimed at decreasing cholesterol levels by the replacement of butter, which contains saturated FAs [78]. It is likely that such dietary modifications affect asthma mechanisms in several ways, and hence, the controversy over the lipid hypothesis continues [79]. For example, FAs may influence the Th cells and the synthesis of Th1/Th2-associated cytokines, which playa basic role in the cell membrane regulating protein function, membrane fluidity and gene expression [80][81].

All PUFAs are necessary for normal epidermal structure and function, and a reduction in the levels of both n3 and n6 PUFAs, brought about by an inherent abnormality of D6-desaturase, has been suggested as paving the way for the presentation of AD [82][83]. The consumption of oily fish rich in the n-3 PUFAs EPA and DHA [84] is an integral constituent of the lipid hypothesis. The original MedDi score did not include high fish intake, but as fish is also a key constituent of the contemporary MedDi, this parameter was added in a later modification [85]; the people of Crete have been reported to consume up to 30-fold more fish than their US peers [86]. Whether there is a meaningful difference between oily and non-oily fish is under debate [87][88], and at least one study has reported similar protective effects of maternal prenatal intake of non-oily fish and intake of both non-oily and oily fish, on the development of asthma/atopy in the offspring [89]; hence, an atopy-modifying effect of non-oily fish cannot be dismissed.

Both observational and intervention studies support a protective effect of prenatal maternal fish intake on asthma/atopy in the offspring (Table 1), but in the epidemiological approach, a variety of factors appear to modify this effect diversely, and occasionally contradictorily. In one US case-control study, monthly oily fish intake during pregnancy was associated with a reduced asthma risk in childhood, but only in children born to asthmatic mothers [87]. A high maternal plasma n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio in the second trimester of pregnancy was associated with current wheeze, current asthma and diagnosed asthma in 1019 children at the age of 4 to 6 years; male sex and maternal asthma increased the risk of wheeze and asthma [63]. Conversely, in a cross-sectional study from Italy, weekly prenatal fish consumption protected from skin prick test (SPT)-evidenced atopy, but only in children born to non-allergic mothers [90]. In a study from Mexico, weekly fish consumption during pregnancy safe guarded the offspring of mothers both with and without a history of allergy from AD, SPT-evidenced atopy and wheeze; adjustment for breastfeeding nullified the wheeze-related effect [91]. In a racially diverse cohort of 1131 pregnant women in the US, 67% were African-American and 42% had a history of atopic disease; 17% of their children had AD, and a higher level of n-6 PUFAs in the second trimester of pregnancy was associated with AD in the children of women with atopy [43].

Table 1. Synopsis of the effect of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and n3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and vitamins A, C and E on asthma and atopy outcomes, and the effect of Vitamin D on bronchial and atopy outcomes.

| Type of Lipids | Asthma/Atopy Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MUFAs | • Reduced risk of asthma/atopy | [70][92] |

| • Cell membranes support-reduced AD | [93] | |

| n-3 PUFAs (fish oils) | Prenatal | |

| • reduced risk of wheeze/asthma | [62][63][66][67][87][94] | |

| • respiratory infections | [65] | |

| • atopy | [90][91][95] | |

| • AD | [96] | |

| Postnatal | ||

| observational: protection on asthma, atopy | [26][69][97][98][99][100][101][102][103] | |

| interventional: inconclusive on | ||

| • AD | [104][105] | |

| • asthma/wheeze | [66][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113] | |

| • worsening on asthma in aspirin-intolerant patients | [114][115] | |

| n-6 PUFAs | Prenatal | |

| no effect or increased risk of | ||

| • AD | [43][116][117] | |

| • atopy | [118] | |

| Postnatal | ||

| • contradictory results on AD and asthma | [119][120][121][122] | |

| Trans-fat | Increased risk of asthma/atopy | [123][124][125][126] |

| Saturated FAs | Increased | |

| • bronchial hyperresponsiveness | [127] | |

| • asthma | [128] | |

| • atopy | [129] | |

| Vitamins C, E, A (fruits and vegetables) | Prenatal | |

| • observational: conflicting evidence on asthma/atopy | [130] | |

| • interventional: lack of evidence | ||

| Postnatal | ||

| • observational: generally favorable on asthma/wheeze, atopy | [43][50][131][132][133][134][135][136][137][138][139][140] | |

| • interventional: conflicting evidence, nutrient specific | [12][141][142][143][144][145][146][147][148] | |

| Vitamin D | Prenatal | |

| • observational: generally favorable on bronchial outcomes | [12][13][149][150][151][152][153] | |

| • interventional: favorable when mother has asthma | [154][155][156] | |

| Postnatal | ||

| • observational: favorable on asthma/atopy | [157][158][159] | |

| • interventional: favorable on asthma/atopy | [160][161] |

3.2. The Antioxidant Hypothesis

The antioxidant hypothesis was proposed in 1994 by Seaton and colleagues [10], who suggested that a Westernized diet, progressively deficient in antioxidants, could be held accountable for the rising prevalence of atopy. Accumulating evidence indicates the possible involvement of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of inflammatory disorders such as asthma and allergic rhinitis [44][162][163].

The lungs are susceptible to oxidative injury because of their high oxygen environment, large surface area and rich blood supply [164]; hence the respiratory system has evolved elaborate antioxidant defenses, including three key antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase and catalase, and numerous non-enzymatic antioxidant compounds, including glutathione, vitamins C and E, α-tocopherol, lycopene, β-carotene, and others. Disruption in the redox balance may favor asthma induction [165].

Maternal consumption of a MedDi rich in fruits, vegetables, fish and vitamin D-containing foods has been shown to exert possible benefit against the development of allergies and asthma [21], or at least to protect small airway function, in childhood [166]. Fruit and vegetables commonly consumed by Mediterranean populations [24], particularly those produced locally, such as oranges, cherries, grapes and tomatoes [167][168], are rich in antioxidants, such as glutathione, vitamin C, vitamin E, vitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids (α-carotene, β-carotene, β- cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin and lycopene), and polyphenols (primarily flavonoids) [44][168]. Numerous observational studies have suggested a protective effect of high postnatal (childhood/adult) consumption of such foods against asthma/allergic rhinitis [50][169] and atopy/AD [132][167].

Interpretation of these findings should not overlook the effect of specific micronutrients on the outcomes investigated. For instance, low dietary vitamin C intake, and low levels of serum such as corbate have been associated with current wheeze [133], asthma and reduced ventilatory function in numerous epidemiological studies, possibly confirming that vitamin C is a major bronchial antioxidant [134][135]. McEvoy and colleagues in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers showed better pulmonary function at 3 months of age in the offspring of mothers taking vitamin C [170].

Supplementation with vitamin C, however, of even up to 16 weeks, has generally yielded poor results [136], as also concluded by a Cochrane review [137]. Vitamin C supplementation may benefit exercise-induced bronchoconstriction [134], and treatment with high doses of intravenous vitamin C was suggested to control allergy symptoms [138]. The compounded evidence points towards a protective effect of a longstanding habitual diet rich in vitamin C, rather than short-or medium-term supplementation and/or intervention in already established asthma [43][133].

The case for vitamin E is similar; vitamin E is the principal defense against oxidant-induced membrane injury [171]; its dietary sources are olive oil, olives, nuts and avocado [172], which are key constituents of the MedDi. Vitamin E, in contrast to vitamin C, exerts additional non-antioxidant immune-regulating action in the form of the modulation of IL-4 gene expression, production of eicosanoid and IgE, neutrophil migration and allergen-induced monocyte proliferation [173][174].

Intervention studies in the postnatal setting have produced conflicting findings [141][142][143]. Considerable epidemiological evidence suggests a protective role against asthma for vitamin E [143] although there are also reports of no benefit [144], possibly indicative of the opposing regulatory effects of the tocopherol isoforms of vitamin E [145]. Favorable reports have been produced in the prenatal observational setting, with some studies showing a protective effect of high maternal prenatal consumption on asthma/AD outcomes in the offspring [130]. This may reflect the immune modulating action of vitamin E during a critical period for immune system ontogeny. As with vitamin C, habitual dietary intake of vitamin E may protect against asthma, but this may be due to interaction between closely related nutrients; for example, concurrent vitamin C and E supplementation was observed to protect against bronchoconstriction in one cross-sectional study in preschool children [139], but firm conclusions could not be drawn on the effectiveness of vitamin C and E on either asthma control or exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, in a systematic review by Wilkinson and colleagues [140].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14091825

References

- Christiansen, E.S.; Kjaer, H.F.; Eller, E.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Høst, A.; Mortz, C.G.; Halken, S. The Prevalence of Atopic Diseases and the Patterns of Sensitization in Adolescence. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27, 847–853.

- Smith, P.K.; Masilamani, M.; Li, X.-M.; Sampson, H.A. The False Alarm Hypothesis: Food Allergy Is Associated with High Dietary Advanced Glycation End-Products and Proglycating Dietary Sugars That Mimic Alarmins. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 429–437.

- McKenzie, C.; Silverberg, J.I. The Prevalence and Persistence of Atopic Dermatitis in Urban United States Children. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 123, 173–178.e1.

- Papadopoulos, N.G.; Miligkos, M.; Xepapadaki, P. A Current Perspective of Allergic Asthma: From Mechanisms to Management. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 268, 69–93.

- Musaad, S.M.A.; Paige, K.N.; Teran-Garcia, M.; Donovan, S.M.; Fiese, B.H. Childhood Overweight/Obesity and Pediatric Asthma: The Role of Parental Perception of Child Weight Status. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3713–3729.

- Murrison, L.B.; Brandt, E.B.; Myers, J.B.; Hershey, G.K.K. Environmental Exposures and Mechanisms in Allergy and Asthma Development. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 1504–1515.

- Asher, M.I.; García-Marcos, L.; Pearce, N.E.; Strachan, D.P. Trends in Worldwide Asthma Prevalence. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002094.

- Fortun, M.; Fortun, K.; Costelloe-Kuehn, B.; Saheb, T.; Price, D.; Kenner, A.; Crowder, J. Asthma, Culture, and Cultural Analysis: Continuing Challenges. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 795, 321–332.

- Burney, P.G. The Causes of Asthma–Does Salt Potentiate Bronchial Activity? Discussion Paper. J. R. Soc. Med. 1987, 80, 364–367.

- Seaton, A.; Godden, D.J.; Brown, K. Increase in Asthma: A More Toxic Environment or a More Susceptible Population? Thorax 1994, 49, 171–174.

- Garcia-Larsen, V.; Del Giacco, S.R.; Moreira, A.; Bonini, M.; Charles, D.; Reeves, T.; Carlsen, K.-H.; Haahtela, T.; Bonini, S.; Fonseca, J.; et al. Asthma and Dietary Intake: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Allergy 2016, 71, 433–442.

- Allan, K.; Devereux, G. Diet and Asthma: Nutrition Implications from Prevention to Treatment. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 258–268.

- Nurmatov, U.; Devereux, G.; Sheikh, A. Nutrients and Foods for the Primary Prevention of Asthma and Allergy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 724–733.e30.

- Robison, R.; Kumar, R. The Effect of Prenatal and Postnatal Dietary Exposures on Childhood Development of Atopic Disease. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 10, 139–144.

- Allan, K.; Kelly, F.J.; Devereux, G. Antioxidants and Allergic Disease: A Case of Too Little or Too Much? Clin. Exp. Allergy 2010, 40, 370–380.

- Anandan, C.; Nurmatov, U.; Sheikh, A. Omega 3 and 6 Oils for Primary Prevention of Allergic Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Allergy 2009, 64, 840–848.

- Varraso, R. Nutrition and Asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012, 12, 201–210.

- Arvaniti, F.; Priftis, K.N.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Dietary Habits and Asthma: A Review. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010, 31, e1–e10.

- Perkins, T.N.; Oczypok, E.A.; Dutz, R.E.; Donnell, M.L.; Myerburg, M.M.; Oury, T.D. The Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products Is a Critical Mediator of Type 2 Cytokine Signaling in the Lungs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 796–808.e12.

- Worldwide Variations in the Prevalence of Asthma Symptoms: The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Eur. Respir. J. 1998, 12, 315–335.

- Chatzi, L.; Kogevinas, M. Prenatal and Childhood Mediterranean Diet and the Development of Asthma and Allergies in Children. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1629–1634.

- Garcia-Marcos, L. Mediterranean Diet as a Protection against Asthma: Still Another Brick in Building a Causative Association. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2016, 44, 97–98.

- Biagi, C.; Di Nunzio, M.; Bordoni, A.; Gori, D.; Lanari, M. Effect of Adherence to Mediterranean Diet during Pregnancy on Children’s Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 997.

- Mazzocchi, A.; Leone, L.; Agostoni, C.; Pali-Schöll, I. The Secrets of the Mediterranean Diet. Does Olive Oil Matter? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2941.

- Hidalgo-Mora, J.J.; García-Vigara, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.L.; García-Pérez, M.-Á.; Tarín, J.; Cano, A. The Mediterranean Diet: A Historical Perspective on Food for Health. Maturitas 2020, 132, 65–69.

- Sikalidis, A.K.; Kelleher, A.H.; Kristo, A.S. Mediterranean Diet. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 31.

- Eleftheriou, D.; Benetou, V.; Trichopoulou, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Bamia, C. Mediterranean Diet and Its Components in Relation to All-Cause Mortality: Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 1081–1097.

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Hershey, M.S.; Zazpe, I.; Trichopoulou, A. Transferability of the Mediterranean Diet to Non-Mediterranean Countries. What Is and What Is Not the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1226.

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153.

- Menotti, A.; Puddu, P.E. How the Seven Countries Study Contributed to the Definition and Development of the Mediterranean Diet Concept: A 50-Year Journey. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 245–252.

- Tourlouki, E.; Matalas, A.-L.; Bountziouka, V.; Tyrovolas, S.; Zeimbekis, A.; Gotsis, E.; Tsiligianni, I.; Protopapa, I.; Protopapas, C.; Metallinos, G.; et al. Are Current Dietary Habits in Mediterranean Islands a Reflection of the Past? Results from the MEDIS Study. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2013, 52, 371–386.

- Belahsen, R. Nutrition Transition and Food Sustainability. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 385–388.

- Konieczna, J.; Yañez, A.; Moñino, M.; Babio, N.; Toledo, E.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Sorlí, J.V.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; et al. Longitudinal Changes in Mediterranean Diet and Transition between Different Obesity Phenotypes. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 966–975.

- Garcia-Closas, R.; Berenguer, A.; González, C.A. Changes in Food Supply in Mediterranean Countries from 1961 to 2001. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 53–60.

- Apostolaki, I.; Pepa, A.; Magriplis, E.; Malisova, O.; Kapsokefalou, M. Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Social Capital and Health Related Quality of Life in the Older Adults of Crete, Greece: The MINOA Study. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 13, 149–161.

- Nowak, D.; Gośliński, M.; Popławski, C. Antioxidant Properties and Fatty Acid Profile of Cretan Extra Virgin Bioolive Oils: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 5554002.

- Garcia-Larsen, V.; Luczynska, M.; Kowalski, M.L.; Voutilainen, H.; Ahlström, M.; Haahtela, T.; Toskala, E.; Bockelbrink, A.; Lee, H.-H.; Vassilopoulou, E.; et al. Use of a Common Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) to Assess Dietary Patterns and Their Relation to Allergy and Asthma in Europe: Pilot Study of the GA2LEN FFQ. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 750–756.

- Tapsell, L.C.; Neale, E.P.; Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Foods, Nutrients, and Dietary Patterns: Interconnections and Implications for Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 445–454.

- Barabasi, A.-L.; Menichetti, G.; Loscalzo, J. The Unmapped Chemical Complexity of Our Diet. Nat. Food 2019, 1, 33–37.

- Lv, N.; Xiao, L.; Ma, J. Dietary Pattern and Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Asthma Allergy 2014, 7, 105–121.

- Bédard, A.; Li, Z.; Ait-Hadad, W.; Camargo, C.A.J.; Leynaert, B.; Pison, C.; Dumas, O.; Varraso, R. The Role of Nutritional Factors in Asthma: Challenges and Opportunities for Epidemiological Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3013.

- Forte, G.C.; da Silva, D.T.R.; Hennemann, M.L.; Sarmento, R.A.; Almeida, J.C.; de Tarso Roth Dalcin, P. Diet Effects in the Asthma Treatment: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1878–1887.

- Han, Y.-Y.; Forno, E.; Holguin, F.; Celedón, J.C. Diet and Asthma: An Update. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 15, 369–374.

- Guilleminault, L.; Williams, E.J.; Scott, H.A.; Berthon, B.S.; Jensen, M.; Wood, L.G. Diet and Asthma: Is It Time to Adapt Our Message? Nutrients 2017, 9, 1227.

- De Batlle, J.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Antó, J.M.; Romieu, I. Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Reduced Asthma and Rhinitis in Mexican Children. Allergy 2008, 63, 1310–1316.

- Andrianasolo, R.M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Adjibade, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Varraso, R. Associations between Dietary Scores with Asthma Symptoms and Asthma Control in Adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1702572.

- Milà-Villarroel, R.; Bach-Faig, A.; Puig, J.; Puchal, A.; Farran, A.; Serra-Majem, L.; Carrasco, J.L. Comparison and Evaluation of the Reliability of Indexes of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2338–2345.

- Papamichael, M.M.; Shrestha, S.K.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Erbas, B. The Role of Fish Intake on Asthma in Children: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 29, 350–360.

- Yang, H.; Xun, P.; He, K. Fish and Fish Oil Intake in Relation to Risk of Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80048.

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Konstantinou, G.N.; Dimitriou, A.; Manios, Y.; Koumbi, L.; Papadopoulos, N.G. The Impact of Food Histamine Intake on Asthma Activity: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3402.

- McKeever, T.M.; Britton, J. Diet and Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 725–729.

- Lee-Sarwar, K.; Litonjua, A.A. As You Eat It: Effects of Prenatal Nutrition on Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 711–718.

- Von Mutius, E.; Smits, H.H. Primary Prevention of Asthma: From Risk and Protective Factors to Targeted Strategies for Prevention. Lancet 2020, 396, 854–866.

- Noutsios, G.T.; Floros, J. Childhood Asthma: Causes, Risks, and Protective Factors; a Role of Innate Immunity. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2014, 144, w14036.

- Muraro, A.; Halken, S.; Arshad, S.H.; Beyer, K.; Dubois, A.E.J.; Du Toit, G.; Eigenmann, P.A.; Grimshaw, K.E.C.; Hoest, A.; Lack, G.; et al. EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines. Primary Prevention of Food Allergy. Allergy 2014, 69, 590–601.

- Sonnenschein-van der Voort, A.M.M.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; van der Valk, R.J.P.; Willemsen, S.P.; Hofman, A.; Moll, H.A.; de Jongste, J.C.; Duijts, L. Duration and Exclusiveness of Breastfeeding and Childhood Asthma-Related Symptoms. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 39, 81–89.

- Erratum to Supplement—The Pregnancy and Birth to 24 Months Project: A Series of Systematic Reviews on Diet and Health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 1041.

- Güngör, D.; Nadaud, P.; LaPergola, C.C.; Dreibelbis, C.; Wong, Y.P.; Terry, N.; Abrams, S.A.; Beker, L.; Jacobovits, T.; Järvinen, K.M.; et al. Infant Milk-Feeding Practices and Food Allergies, Allergic Rhinitis, Atopic Dermatitis, and Asthma throughout the Life Span: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109 (Suppl. 7), 772S–799S.

- Lodge, C.J.; Tan, D.J.; Lau, M.X.Z.; Dai, X.; Tham, R.; Lowe, A.J.; Bowatte, G.; Allen, K.J.; Dharmage, S.C. Breastfeeding and Asthma and Allergies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 38–53.

- Kim, J.H. Role of Breast-Feeding in the Development of Atopic Dermatitis in Early Childhood. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017, 9, 285–287.

- Lin, B.; Dai, R.; Lu, L.; Fan, X.; Yu, Y. Breastfeeding and Atopic Dermatitis Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Dermatology 2020, 236, 345–360.

- Mickleborough, T.D.; Rundell, K.W. Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Asthma- and Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 1335–1346.

- Rosa, M.J.; Hartman, T.J.; Adgent, M.; Gardner, K.; Gebretsadik, T.; Moore, P.E.; Davis, R.L.; LeWinn, K.Z.; Bush, N.R.; Tylavsky, F.; et al. Prenatal Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Child Asthma: Effect Modification by Maternal Asthma and Child Sex. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 800–807.e4.

- Mayor, S. High Dose Fish Oil Supplements in Late Pregnancy Reduce Asthma in Offspring, Finds Study. BMJ 2016, 356, i6861.

- Chercoles, E.R. Fish Oil-Derived Fatty Acids in Pregnancy and Wheeze and Asthma in Offspring. Acta Pediatr. Esp. 2017, 75, 81.

- Rago, D.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Lee-Sarwar, K.A.; Weiss, S.T.; Lasky-Su, J.; Stokholm, J.; Bønnelykke, K.; Chawes, B.L.; Bisgaard, H. Fish-Oil Supplementation in Pregnancy, Child Metabolomics and Asthma Risk. EBioMedicine 2019, 46, 399–410.

- Hansen, S.; Strøm, M.; Maslova, E.; Dahl, R.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Rytter, D.; Bech, B.H.; Henriksen, T.B.; Granström, C.; Halldorsson, T.I.; et al. Fish Oil Supplementation during Pregnancy and Allergic Respiratory Disease in the Adult Offspring. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 104–111.e4.

- Black, P.N.; Sharpe, S. Dietary Fat and Asthma: Is There a Connection? Eur. Respir. J. 1997, 10, 6–12.

- Wendell, S.G.; Baffi, C.; Holguin, F. Fatty Acids, Inflammation, and Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1255–1264.

- Jandacek, R.J. Linoleic Acid: A Nutritional Quandary. Healthcare 2017, 5, 25.

- Hanna, V.S.; Hafez, E.A.A. Synopsis of Arachidonic Acid Metabolism: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 11, 23–32.

- Schmid, T.; Brüne, B. Prostanoids and Resolution of Inflammation—Beyond the Lipid-Mediator Class Switch. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 2838.

- Xue, L.; Fergusson, J.; Salimi, M.; Panse, I.; Ussher, J.E.; Hegazy, A.N.; Vinall, S.L.; Jackson, D.G.; Hunter, M.G.; Pettipher, R.; et al. Prostaglandin D2 and Leukotriene E4 Synergize to Stimulate Diverse TH2 Functions and TH2 Cell/Neutrophil Crosstalk. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 1311–1358.

- Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease? Nutrients 2017, 9, 784.

- Schmitz, G.; Ecker, J. The Opposing Effects of N-3 and n-6 Fatty Acids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2008, 47, 147–155.

- Mariamenatu, A.H.; Abdu, E.M. Overconsumption of Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) versus Deficiency of Omega-3 PUFAs in Modern-Day Diets: The Disturbing Factor for Their “Balanced Antagonistic Metabolic Functions” in the Human Body. J. Lipids 2021, 2021, 8848161.

- Joffre, C.; Rey, C.; Layé, S. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and the Resolution of Neuroinflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1022.

- Liu, Q.; Rossouw, J.E.; Roberts, M.B.; Liu, S.; Johnson, K.C.; Shikany, J.M.; Manson, J.E.; Tinker, L.F.; Eaton, C.B. Theoretical Effects of Substituting Butter with Margarine on Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Epidemiology 2017, 28, 145–156.

- Oliver, P.J.; Arutla, S.; Yenigalla, A.; Hund, T.J.; Parinandi, N.L. Lipid Nutrition in Asthma. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 79, 669–694.

- Mamareli, P.; Kruse, F.; Lu, C.-W.; Guderian, M.; Floess, S.; Rox, K.; Allan, D.S.J.; Carlyle, J.R.; Brönstrup, M.; Müller, R.; et al. Targeting Cellular Fatty Acid Synthesis Limits T Helper and Innate Lymphoid Cell Function during Intestinal Inflammation and Infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 164–176.

- Howie, D.; Ten Bokum, A.; Necula, A.S.; Cobbold, S.P.; Waldmann, H. The Role of Lipid Metabolism in T Lymphocyte Differentiation and Survival. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1949.

- Fujii, M.; Nakashima, H.; Tomozawa, J.; Shimazaki, Y.; Ohyanagi, C.; Kawaguchi, N.; Ohya, S.; Kohno, S.; Nabe, T. Deficiency of N-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Is Mainly Responsible for Atopic Dermatitis-like Pruritic Skin Inflammation in Special Diet-Fed Hairless Mice. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 272–277.

- Sawada, Y.; Saito-Sasaki, N.; Nakamura, M. Omega 3 Fatty Acid and Skin Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 3818.

- Zhang, T.-T.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.-M.; Xue, C.-H. Health Benefits of Dietary Marine DHA/EPA-Enriched Glycerophospholipids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2019, 75, 100997.

- De Koning, L.; Anand, S.S. Vascular viewpoint. Vasc. Med. 2004, 9, 145–146.

- Simopoulos, A.P. The Mediterranean Diets: What Is so Special about the Diet of Greece? The Scientific Evidence. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 3065S–3073S.

- Salam, M.T.; Li, Y.-F.; Langholz, B.; Gilliland, F.D. Maternal Fish Consumption during Pregnancy and Risk of Early Childhood Asthma. J. Asthma 2005, 42, 513–518.

- Lumia, M.; Luukkainen, P.; Tapanainen, H.; Kaila, M.; Erkkola, M.; Uusitalo, L.; Niinistö, S.; Kenward, M.G.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; et al. Dietary Fatty Acid Composition during Pregnancy and the Risk of Asthma in the Offspring. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2011, 22, 827–835.

- Romieu, I.; Torrent, M.; Garcia-Esteban, R.; Ferrer, C.; Ribas-Fitó, N.; Antó, J.M.; Sunyer, J. Maternal Fish Intake during Pregnancy and Atopy and Asthma in Infancy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2007, 37, 518–525.

- Calvani, M.; Alessandri, C.; Miceli Sopo, S.; Panetta, V.; Pingitore, G.; Tripodi, S.; Zappalà, D.; Zicari, A. Consumption of Fish, Butter and Margarine during Pregnancy and Development of Allergic Sensitizations in the Offspring: Role of Maternal Atopy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 17, 94–102.

- Fogarty, A.; Britton, J. The Role of Diet in the Aetiology of Asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 30, 615–627.

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608.

- Carlson, S.J.; Fallon, E.M.; Kalish, B.T.; Gura, K.M.; Puder, M. The Role of the ω-3 Fatty Acid DHA in the Human Life Cycle. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 15–22.

- Olsen, S.F.; Østerdal, M.L.; Salvig, J.D.; Mortensen, L.M.; Rytter, D.; Secher, N.J.; Henriksen, T.B. Fish Oil Intake Compared with Olive Oil Intake in Late Pregnancy and Asthma in the Offspring: 16 y of Registry-Based Follow-up from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 167–175.

- Pike, K.C.; Calder, P.C.; Inskip, H.M.; Robinson, S.M.; Roberts, G.C.; Cooper, C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Lucas, J.S.A. Maternal Plasma Phosphatidylcholine Fatty Acids and Atopy and Wheeze in the Offspring at Age of 6 Years. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 474613.

- Dunstan, J.A.; Mori, T.A.; Barden, A.; Beilin, L.J.; Taylor, A.L.; Holt, P.G.; Prescott, S.L. Fish Oil Supplementation in Pregnancy Modifies Neonatal Allergen-Specific Immune Responses and Clinical Outcomes in Infants at High Risk of Atopy: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 112, 1178–1184.

- Alm, B.; Aberg, N.; Erdes, L.; Möllborg, P.; Pettersson, R.; Norvenius, S.G.; Goksör, E.; Wennergren, G. Early Introduction of Fish Decreases the Risk of Eczema in Infants. Arch. Dis. Child. 2009, 94, 11–15.

- Greer, F.R.; Sicherer, S.H.; Burks, A.W. The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20190281.

- Nafstad, P.; Nystad, W.; Magnus, P.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis at 4 Years of Age in Relation to Fish Consumption in Infancy. J. Asthma 2003, 40, 343–348.

- Antova, T.; Pattenden, S.; Nikiforov, B.; Leonardi, G.S.; Boeva, B.; Fletcher, T.; Rudnai, P.; Slachtova, H.; Tabak, C.; Zlotkowska, R.; et al. Nutrition and Respiratory Health in Children in Six Central and Eastern European Countries. Thorax 2003, 58, 231–236.

- Ellwood, P.; Asher, M.I.; Björkstén, B.; Burr, M.; Pearce, N.; Robertson, C.F. Diet and Asthma, Allergic Rhinoconjunctivitis and Atopic Eczema Symptom Prevalence: An Ecological Analysis of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Data. ISAAC Phase One Study Group. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 17, 436–443.

- Miles, E.A.; Childs, C.E.; Calder, P.C. Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (LCPUFAs) and the Developing Immune System: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 247.

- Kim, E.; Ju, S.-Y. Asthma and Dietary Intake of Fish, Seaweeds, and Fatty Acids in Korean Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2187.

- Eriksen, B.B.; Kåre, D.L. Open Trial of Supplements of Omega 3 and 6 Fatty Acids, Vitamins and Minerals in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2006, 17, 82–85.

- Søyland, E.; Funk, J.; Rajka, G.; Sandberg, M.; Thune, P.; Rustad, L.; Helland, S.; Middelfart, K.; Odu, S.; Falk, E.S. Dietary Supplementation with Very Long-Chain n-3 Fatty Acids in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. A Double-Blind, Multicentre Study. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 130, 757–764.

- Hodge, L.; Salome, C.M.; Hughes, J.M.; Liu-Brennan, D.; Rimmer, J.; Allman, M.; Pang, D.; Armour, C.; Woolcock, A.J. Effect of Dietary Intake of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids on Severity of Asthma in Children. Eur. Respir. J. 1998, 11, 361–365.

- Abdo-Sultan, M.K.; Abd-El-Lateef, R.S.; Kamel, F.Z. Efficacy of Omega-3 Fatty Acids Supplementation versus Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Bronchial Asthma. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2019, 26, 79–89.

- Mickleborough, T.D.; Murray, R.L.; Ionescu, A.A.; Lindley, M.R. Fish Oil Supplementation Reduces Severity of Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Elite Athletes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 1181–1189.

- Thien, F.C.; Mencia-Huerta, J.M.; Lee, T.H. Dietary Fish Oil Effects on Seasonal Hay Fever and Asthma in Pollen-Sensitive Subjects. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993, 147, 1138–1143.

- Kremmyda, L.-S.; Vlachava, M.; Noakes, P.S.; Diaper, N.D.; Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Atopy Risk in Infants and Children in Relation to Early Exposure to Fish, Oily Fish, or Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids: A Systematic Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 41, 36–66.

- Mihrshahi, S.; Peat, J.K.; Webb, K.; Tovey, E.R.; Marks, G.B.; Mellis, C.M.; Leeder, S.R. The Childhood Asthma Prevention Study (CAPS): Design and Research Protocol of a Randomized Trial for the Primary Prevention of Asthma. Control. Clin. Trials 2001, 22, 333–354.

- Gunaratne, A.W.; Makrides, M.; Collins, C.T. Maternal Prenatal and/or Postnatal n-3 Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (LCPUFA) Supplementation for Preventing Allergies in Early Childhood. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015.

- Muley, P.; Shah, M.; Muley, A. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Supplementation in Children to Prevent Asthma: Is It Worthy?—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy 2015, 2015, 312052.

- Zambalde, É.P.; Teixeira, M.M.; Favarin, D.C.; de Oliveira, J.R.; Magalhães, M.L.; Cunha, M.M.; Silva, W.C.J.; Okuma, C.H.; Rodrigues, V.J.; Levy, B.D.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory and pro-Resolution Effects of Aspirin-Triggered RvD1 (AT-RvD1) on Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells from Patients with Severe Asthma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 35, 142–148.

- Schneider, T.R.; Johns, C.B.; Palumbo, M.L.; Murphy, K.C.; Cahill, K.N.; Laidlaw, T.M. Dietary Fatty Acid Modification for the Treatment of Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease: A Prospective Pilot Trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 825–831.

- Standl, M.; Demmelmair, H.; Koletzko, B.; Heinrich, J. Cord Blood LC-PUFA Composition and Allergic Diseases during the First 10 Yr. Results from the LISAplus Study. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2014, 25, 344–350.

- Kang, C.-M.; Chiang, B.-L.; Wang, L.-C. Maternal Nutritional Status and Development of Atopic Dermatitis in Their Offspring. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 61, 128–155.

- Galli, E.; Picardo, M.; Chini, L.; Passi, S.; Moschese, V.; Terminali, O.; Paone, F.; Fraioli, G.; Rossi, P. Analysis of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Newborn Sera: A Screening Tool for Atopic Disease? Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 130, 752–756.

- Horrobin, D.F. Essential Fatty Acid Metabolism and Its Modification in Atopic Eczema. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71 (Suppl. 1), 367S–372S.

- Mayser, P.; Mayer, K.; Mahloudjian, M.; Benzing, S.; Krämer, H.-J.; Schill, W.-B.; Seeger, W.; Grimminger, F. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of n-3 versus n-6 Fatty Acid-Based Lipid Infusion in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2002, 26, 151–158.

- Almqvist, C.; Garden, F.; Xuan, W.; Mihrshahi, S.; Leeder, S.R.; Oddy, W.; Webb, K.; Marks, G.B. Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acid Exposure from Early Life Does Not Affect Atopy and Asthma at Age 5 Years. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, 1438–1444.

- Venter, C.; Meyer, R.W.; Nwaru, B.I.; Roduit, C.; Untersmayr, E.; Adel-Patient, K.; Agache, I.; Agostoni, C.; Akdis, C.A.; Bischoff, S.C.; et al. EAACI Position Paper: Influence of Dietary Fatty Acids on Asthma, Food Allergy, and Atopic Dermatitis. Allergy 2019, 74, 1429–1444.

- Wu, W.; Lin, L.; Shi, B.; Jing, J.; Cai, L. The Effects of Early Life Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Ruminant Trans Fatty Acids on Allergic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1802–1815.

- Weiland, S.K.; von Mutius, E.; Hüsing, A.; Asher, M.I. Intake of Trans Fatty Acids and Prevalence of Childhood Asthma and Allergies in Europe. ISAAC Steering Committee. Lancet 1999, 353, 2040–2041.

- Kuhnt, K.; Degen, C.; Jahreis, G. Evaluation of the Impact of Ruminant Trans Fatty Acids on Human Health: Important Aspects to Consider. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1964–1980.

- Jiménez-Cepeda, A.; Dávila-Said, G.; Orea-Tejeda, A.; González-Islas, D.; Elizondo-Montes, M.; Pérez-Cortes, G.; Keirns-Davies, C.; Castillo-Aguilar, L.F.; Verdeja-Vendrell, L.; Peláez-Hernández, V.; et al. Dietary Intake of Fatty Acids and Its Relationship with FEV1/FVC in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 29, 92–96.

- Kompauer, I.; Demmelmair, H.; Koletzko, B.; Bolte, G.; Linseisen, J.; Heinrich, J. Association of Fatty Acids in Serum Phospholipids with Lung Function and Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness in Adults. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 23, 175–190.

- Wood, L.G. Diet, Obesity, and Asthma. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14 (Suppl. 5), S332–S338.

- Trak-Fellermeier, M.A.; Brasche, S.; Winkler, G.; Koletzko, B.; Heinrich, J. Food and Fatty Acid Intake and Atopic Disease in Adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2004, 23, 575–582.

- Allan, K.M.; Prabhu, N.; Craig, L.C.A.; McNeill, G.; Kirby, B.; McLay, J.; Helms, P.J.; Ayres, J.G.; Seaton, A.; Turner, S.W.; et al. Maternal Vitamin D and E Intakes during Pregnancy Are Associated with Asthma in Children. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1027–1036.

- Hosseini, B.; Berthon, B.S.; Wark, P.; Wood, L.G. Effects of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Risk of Asthma, Wheezing and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 341.

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Vardaka, E.; Efthymiou, D.; Pitsios, C. Early Life Triggers for Food Allergy That in Turn Impacts Dietary Habits in Childhood. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2021, 49, 146–152.

- Forastiere, F.; Pistelli, R.; Sestini, P.; Fortes, C.; Renzoni, E.; Rusconi, F.; Dell’Orco, V.; Ciccone, G.; Bisanti, L. Consumption of Fresh Fruit Rich in Vitamin C and Wheezing Symptoms in Children. SIDRIA Collaborative Group, Italy (Italian Studies on Respiratory Disorders in Children and the Environment). Thorax 2000, 55, 283–288.

- Hemilä, H. The Effect of Vitamin C on Bronchoconstriction and Respiratory Symptoms Caused by Exercise: A Review and Statistical Analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2014, 10, 58.

- Hemilä, H. Vitamin C and Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1216.

- Fogarty, A.; Lewis, S.A.; Scrivener, S.L.; Antoniak, M.; Pacey, S.; Pringle, M.; Britton, J. Oral Magnesium and Vitamin C Supplements in Asthma: A Parallel Group Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2003, 33, 1355–1359.

- Kaur, B.; Rowe, B.H.; Stovold, E. Vitamin C Supplementation for Asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2013, CD000993.

- Vollbracht, C.; Raithel, M.; Krick, B.; Kraft, K.; Hagel, A.F. Intravenous Vitamin C in the Treatment of Allergies: An Interim Subgroup Analysis of a Long-Term Observational Study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 3640–3655.

- Riccioni, G.; Barbara, M.; Bucciarelli, T.; di Ilio, C.; D’Orazio, N. Antioxidant Vitamin Supplementation in Asthma. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2007, 37, 96–101.

- Wilkinson, M.; Hart, A.; Milan, S.J.; Sugumar, K. Vitamins C and E for Asthma and Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction. Cochrane database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD010749.

- Cook-Mills, J.M.; Averill, S.H.; Lajiness, J.D. Asthma, Allergy and Vitamin E: Current and Future Perspectives. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 179, 388–402.

- Pearson, P.J.K.; Lewis, S.A.; Britton, J.; Fogarty, A. Vitamin E Supplements in Asthma: A Parallel Group Randomised Placebo Controlled Trial. Thorax 2004, 59, 652–656.

- Ghaffari, J.; Farid Hossiani, R.; Khalilian, A.; Nahanmoghadam, N.; Salehifar, E.; Rafatpanah, H. Vitamin e Supplementation, Lung Functions and Clinical Manifestations in Children with Moderate Asthma: A Randomized Double Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. 2014, 13, 98–103.

- Nwaru, B.I.; Virtanen, S.M.; Alfthan, G.; Karvonen, A.M.; Genuneit, J.; Lauener, R.P.; Dalphin, J.-C.; Hyvärinen, A.; Pfefferle, P.; Riedler, J.; et al. Serum Vitamin E Concentrations at 1 Year and Risk of Atopy, Atopic Dermatitis, Wheezing, and Asthma in Childhood: The PASTURE Study. Allergy 2014, 69, 87–94.

- Cook-Mills, J.M.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; Hartert, T. Two Faces of Vitamin E in the Lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 279–284.

- Tobias, T.A.M.; Wood, L.G.; Rastogi, D. Carotenoids, Fatty Acids and Disease Burden in Obese Minority Adolescents with Asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019, 49, 838–846.

- Bai, Y.-J.; Dai, R.-J. Serum Levels of Vitamin A and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 (25OHD3) as Reflectors of Pulmonary Function and Quality of Life (QOL) in Children with Stable Asthma: A Case-Control Study. Medicine 2018, 97, e9830.

- Marquez, H.A.; Cardoso, W.V. Vitamin A-Retinoid Signaling in Pulmonary Development and Disease. Mol. Cell. Pediatr. 2016, 3, 28.

- Morales, E.; Romieu, I.; Guerra, S.; Ballester, F.; Rebagliato, M.; Vioque, J.; Tardón, A.; Rodriguez Delhi, C.; Arranz, L.; Torrent, M.; et al. Maternal Vitamin D Status in Pregnancy and Risk of Lower Respiratory Tract Infections, Wheezing, and Asthma in Offspring. Epidemiology 2012, 23, 64–71.

- Bountouvi, E.; Douros, K.; Papadopoulou, A. Can Getting Enough Vitamin D during Pregnancy Reduce the Risk of Getting Asthma in Childhood? Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 87.

- Jensen, M.E.; Murphy, V.E.; Gibson, P.G.; Mattes, J.; Camargo, C.A.J. Vitamin D Status in Pregnant Women with Asthma and Its Association with Adverse Respiratory Outcomes during Infancy. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019, 32, 1820–1825.

- Papadopoulos, N.G.; Christodoulou, I.; Rohde, G.; Agache, I.; Almqvist, C.; Bruno, A.; Bonini, S.; Bont, L.; Bossios, A.; Bousquet, J.; et al. Viruses and Bacteria in Acute Asthma Exacerbations—A GA2 LEN-DARE Systematic Review. Allergy 2011, 66, 458–468.

- Guibas, G.V.; Tsolia, M.; Christodoulou, I.; Stripeli, F.; Sakkou, Z.; Papadopoulos, N.G. Distinction between Rhinovirus-Induced Acute Asthma and Asthma-Augmented Influenza Infection. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 48, 536–543.

- Brustad, N.; Eliasen, A.U.; Stokholm, J.; Bønnelykke, K.; Bisgaard, H.; Chawes, B.L. High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy and Asthma in Offspring at the Age of 6 Years. JAMA 2019, 321, 1003–1005.

- Venter, C.; Agostoni, C.; Arshad, S.H.; Ben-Abdallah, M.; Du Toit, G.; Fleischer, D.M.; Greenhawt, M.; Glueck, D.H.; Groetch, M.; Lunjani, N.; et al. Dietary Factors during Pregnancy and Atopic Outcomes in Childhood: A Systematic Review from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 889–912.

- Lu, M.; Litonjua, A.A.; O’Connor, G.T.; Zeiger, R.S.; Bacharier, L.; Schatz, M.; Carey, V.J.; Weiss, S.T.; Mirzakhani, H. Effect of Early and Late Prenatal Vitamin D and Maternal Asthma Status on Offspring Asthma or Recurrent Wheeze. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1234–1241.e3.

- Urashima, M.; Segawa, T.; Okazaki, M.; Kurihara, M.; Wada, Y.; Ida, H. Randomized Trial of Vitamin D Supplementation to Prevent Seasonal Influenza A in Schoolchildren. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1255–1260.

- Xystrakis, E.; Kusumakar, S.; Boswell, S.; Peek, E.; Urry, Z.; Richards, D.F.; Adikibi, T.; Pridgeon, C.; Dallman, M.; Loke, T.K.; et al. Reversing the Defective Induction of IL-10-Secreting Regulatory T Cells in Glucocorticoid-Resistant Asthma Patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 146–155.

- Majak, P.; Olszowiec-Chlebna, M.; Smejda, K.; Stelmach, I. Vitamin D Supplementation in Children May Prevent Asthma Exacerbation Triggered by Acute Respiratory Infection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 1294–1296.

- Papamichael, M.M.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Lambert, K.; Katsardis, C.; Tsoukalas, D.; Erbas, B. Sufficient Vitamin D Status Positively Modified Ventilatory Function in Asthmatic Children Following a Mediterranean Diet Enriched with Fatty Fish Intervention Study. Nutr. Res. 2020, 82, 99–109.

- Ali, N.S.; Nanji, K. A Review on the Role of Vitamin D in Asthma. Cureus 2017, 9, e1288.

- Han, M.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.H. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Pathway in Allergic Rhinitis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1266.

- Brigham, E.P.; Kolahdooz, F.; Hansel, N.; Breysse, P.N.; Davis, M.; Sharma, S.; Matsui, E.C.; Diette, G.; McCormack, M.C. Association between Western Diet Pattern and Adult Asthma: A Focused Review. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 114, 273–280.

- Van der Vliet, A.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.M.W.; Anathy, V. Oxidative Stress in Chronic Lung Disease: From Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Dysregulated Redox Signaling. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 63, 59–69.

- Fitzpatrick, A.M.; Jones, D.P.; Brown, L.A.S. Glutathione Redox Control of Asthma: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 375–408.

- Bédard, A.; Northstone, K.; John Henderson, A.; Shaheen, S.O. Mediterranean Diet during Pregnancy and Childhood Respiratory and Atopic Outcomes: Birth Cohort Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1901215.

- Chatzi, L.; Apostolaki, G.; Bibakis, I.; Skypala, I.; Bibaki-Liakou, V.; Tzanakis, N.; Kogevinas, M.; Cullinan, P. Protective Effect of Fruits, Vegetables and the Mediterranean Diet on Asthma and Allergies among Children in Crete. Thorax 2007, 62, 677–683.

- Barros, R.; Moreira, A.; Fonseca, J.; de Oliveira, J.F.; Delgado, L.; Castel-Branco, M.G.; Haahtela, T.; Lopes, C.; Moreira, P. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Fresh Fruit Intake Are Associated with Improved Asthma Control. Allergy 2008, 63, 917–923.

- Arteaga-Badillo, D.A.; Portillo-Reyes, J.; Vargas-Mendoza, N.; Morales-González, J.A.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Álvarez-González, I.; Morales-González, Á.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Madrigal-Santillán, E. Asthma: New Integrative Treatment Strategies for the Next Decades. Medicina 2020, 56, 438.

- McEvoy, C.T.; Shorey-Kendrick, L.E.; Milner, K.; Schilling, D.; Tiller, C.; Vuylsteke, B.; Scherman, A.; Jackson, K.; Haas, D.M.; Harris, J.; et al. Oral Vitamin C (500 Mg/d) to Pregnant Smokers Improves Infant Airway Function at 3 Months (VCSIP). A Randomized Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1139–1147.

- Jiang, Q. Natural Forms of Vitamin E: Metabolism, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities and Their Role in Disease Prevention and Therapy. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 72, 76–90.

- Shahidi, F.; Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.C.; Fuentes, J.; Speisky, H.; de Camargo, A.C. Vitamin E as an Essential Micronutrient for Human Health: Common, Novel, and Unexplored Dietary Sources. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 176, 312–321.

- Shams, M.-H.; Jafari, R.; Eskandari, N.; Masjedi, M.; Kheirandish, F.; Ganjalikhani Hakemi, M.; Ghasemi, R.; Varzi, A.-M.; Sohrabi, S.-M.; Baharvand, P.A.; et al. Anti-Allergic Effects of Vitamin E in Allergic Diseases: An Updated Review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 90, 107196.

- Lewis, E.D.; Meydani, S.N.; Wu, D. Regulatory Role of Vitamin E in the Immune System and Inflammation. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 487–494.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!