The COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to causing humanitarian and socio-economic emergencies, exposed companies of all sizes and sectors to different and complex challenges, which impacted various aspects of organizational design and behavior [

1]. This is especially the case for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) due to the difficulties that these organizations may encounter in finding the financial resources and human skills necessary to promptly and effectively manage the turmoil deriving from these crises [

2,

3]. Regarding work occupation, the COVID-19 pandemic caused career shocks that were differentiated in the short and long term [

4], as well as significant changes in the status of some occupations and their relative value [

5]. Therefore, organizations and employees had to face a work environment that was profoundly changed by the crisis [

6], with the implementation of remote work practices influencing organizational performance [

7], leading to financial and bureaucratic constraints and making it harder to monitor workers’ output [

8]. Sudden changes following the COVID-19 pandemic could also have a positive or negative impact on employee work-life balance and job performance [

9,

10]. Technological advances, routine planning, and self-discipline become essential to maintaining good standards of work performance, especially when workers had to work from home (WFH) [

11], in which case it was also important to ensure a home environment conducive to work, which could protect physical and mental health at the same time [

12].

This changed situation after the COVID-19 pandemic also led organizations to be exposed to a greater number of risks, including risks related to knowledge management [

13]. Considering the knowledge risks mapped and classified by Durst and Zieba [

14] into human, technological, and operational domains, it can be noted that some of the threats associated with these risks became more serious during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human knowledge risks such as knowledge hiding, unlearning, and forgetting may be more likely to occur in the context of remote working. Employees can easily hide knowledge behind their private screens, while the lack of direct contact with workmates could favor the unlearning and forgetting of valuable knowledge due to communication being virtual and contacts filtered [

13]. Knowledge risks most likely to affect employees who WFH are those related to the use of technology. Knowledge risks related to cybercrime, for example, could occur more easily in a less secure home internet network that could possibly be exposed to hacker attacks or through risky behaviors, such as sharing sensitive files via private devices. Knowledge risks related to old technologies could also affect remote workers, as employees may use outdated programs that do not allow IT security devices to be updated [

13,

14]. SMEs may find it more difficult to maintain their organizational balance—in particular, the balance between work and private life in the case of WFH, while also considering the effects of possible exposure to knowledge risks linked to the use of technology [

15,

16].

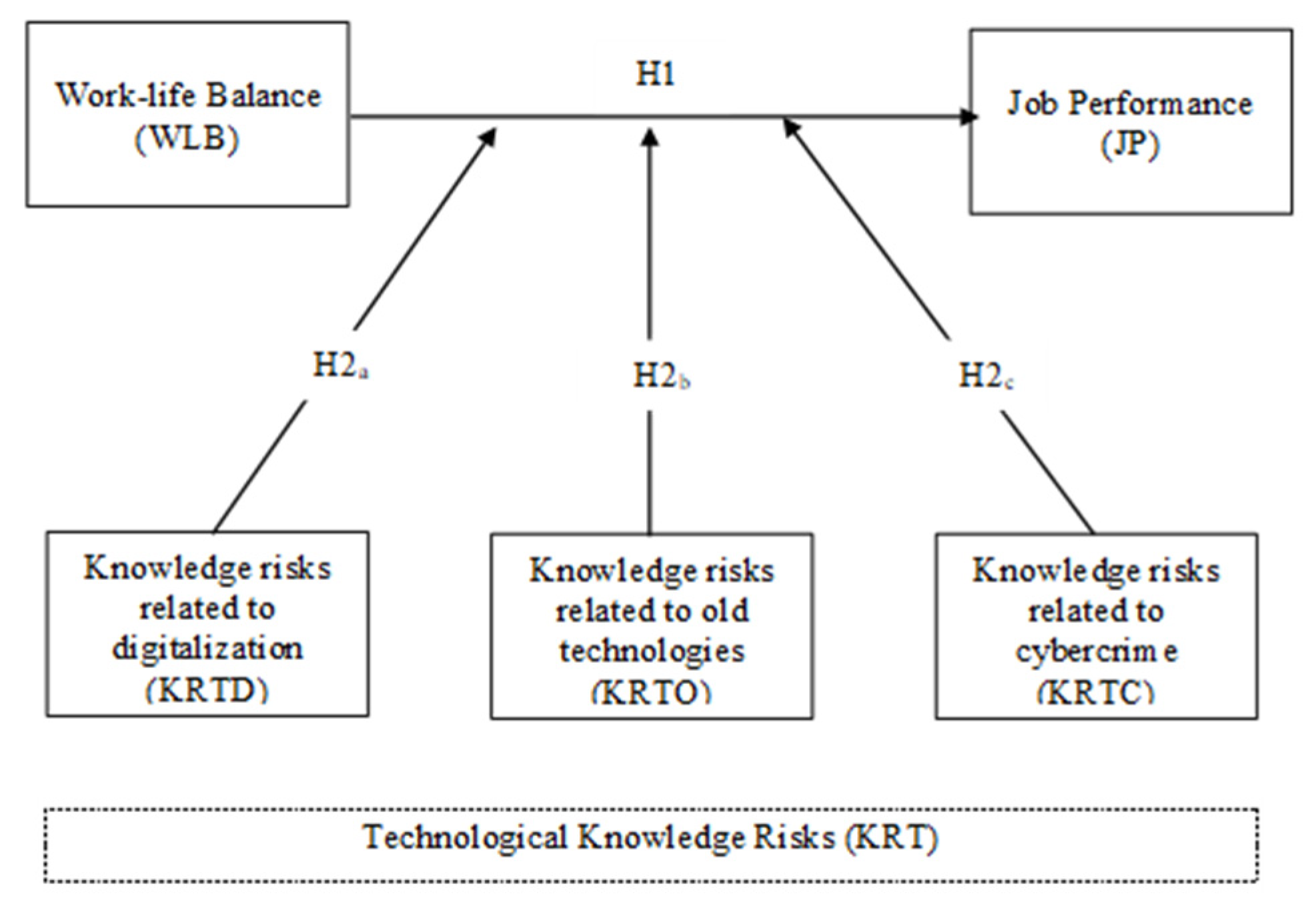

Considering the above, this paper aims to investigate the possible effects of technological knowledge risks (KRT) on the work-life balance (WLB) and job performance (JP) of employees of small banks. In particular, it investigates the moderating effects of KRT in terms of the risk of knowledge digitalization (KRTD), risks related to old technologies (KRTO), and risks related to cybercrime (KRTC) [

17] on the relationship between WLB and JP in cooperative credit banks (CCBs). Haider, Jabeen, and Ahmad [

18] stated that, although many scholars have investigated the WLB/JP relationship, the mechanisms that explain its functioning have still received little consideration. To fill this gap, it may be useful to introduce variables that mediate or moderate this relationship. A statistical analysis of mediation can be applied to check whether the effect of one variable on a second variable is transmitted through a third variable [

19], while moderation occurs when the direction of the effect of a predictor variable on a result variable varies as a function of the value of another variable—that is, the moderator [

20]. The extant literature has highlighted mediating and moderating effects of several variables on the WLB/JP relationship. Baral and Bhargava [

21] examined the mediating role of work-family enrichment in the relationships between organizational interventions for WLB; in another study, optimism was tested as a mediator of the relationship between WLB, life satisfaction, and creative performance [

22]. Furthermore, Sari and Seniati [

23] investigated the effects of WLB on lecturers’ organizational commitment, using job satisfaction as a mediator; meanwhile, Rasheed, Mukhtar, Anwar, and Hayat [

24] focused on the moderating role of obligation felt on employees’ desire for revenge.

2. Knowledge Risks: The State of the Art

Knowledge risk is an emerging field within the areas of knowledge management (KM) and intellectual capital (IC) [

25] that aims to offer solutions to problems related to conventional risk management methods, applying KM tools and techniques for the management of organizational risks [

26].

Knowledge risks have seldom been defined in the literature [

14]. A more complete definition was proposed by Durst and Zieba [

14] (p. 2), who describe knowledge risk as “a measure of the probability and severity of adverse effects of any activities engaging or related somehow to knowledge that can affect the functioning of an organization on any level”. This definition highlights the potential harmfulness of knowledge risks for organizations of all types and sizes, as well as the need to address these risks in relation to each other, preferably following an integrated approach [

27].

The scientific literature on knowledge risks is still fragmented at present, addressing knowledge risks in isolation and often without comparing the organizational contexts involved [

28]. Durst and Zieba [

29] proposed the first taxonomy for knowledge risks to foster more rigorous research on this topic and, at the same time, support organizations in preventing or reducing these risks. Some types of knowledge risks were then identified and categorized according to their origin—internal or external to the organization. The risk of knowledge waste is another problem that occurs within organizations; it arises when valuable knowledge that is available in the organization is not used. An example of a knowledge risk originating outside an organization is knowledge spillover, which occurs when knowledge spills over to competitors, who gain a competitive advantage from it [

29]. In order to further highlight the differences between types of knowledge risk, the same authors [

14] divided knowledge risks into human, technological, and operational types. Human knowledge risks include knowledge hiding, forgetting, and unlearning—i.e., risks linked to the personal, social, psychological, and cultural factors of individuals. An organization is exposed to the risk of knowledge hiding, which is when people intentionally hide knowledge that has been requested by another person for reasons related to their fear of losing a competitive advantage or a position of power. The second category includes knowledge risks related to the use of technology by organizations, such as the risk of cybercrime (e.g., hacker attacks); the risk of digitalization—namely, the excessive dependence of organizations on technology rather than human factors; and risks associated with the obsolescence of organizational technological equipment [

14]. The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened companies’ risk of exposure to KRT, as organizations during this period often resorted to WFH solutions due to the implementation of lockdown measures [

13]. In this regard, it is important to ensure the adoption of cyber-safety behaviors based on digital safety skills in order to maintain a safe digital work environment [

30] and encourage the development of employees’ digital skills to enable them to better cope with the new paradigm of Industry 4.0 [

31]. These skills should also be adequately defined and measured [

32,

33] in order to avoid phenomena such as digital divides and inequality [

34,

35,

36,

37], especially in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, which required considerable efforts from human resources departments to improve the digital skills of employees to allow them to maintain a satisfactory WLB even working remotely [

38,

39].

Operational knowledge risks that can affect organizations in their regular operations include knowledge outsourcing risks, the risk of using outdated/unreliable knowledge, and the risk of knowledge waste [

14].

All organizations can be exposed to one or more knowledge risks, both private [

17,

40] and public [

41]. SMEs are at particular risk, as they may experience greater difficulties in managing knowledge risks due to their lower capital endowments [

42]. Organizational performance [

43], as well as organizations’ ability to achieve economic, social, and environmental sustainability goals, can also be affected by knowledge risks [

44,

45].

Despite these valuable contributions, the research on knowledge risks still needs to be expanded, as this field is in an early stage of development [

46], especially in relation to organizations belonging to the banking and financial sectors. Recent contributions have confirmed these findings, highlighting that very few studies clearly refer to one or more knowledge risks affecting banks or other financial companies [

47], despite risk culture being strongly rooted in these organizations [

48].

3. Latest Trends on Work-Life Balance

The extant literature on this topic has provided multiple definitions of WLB, focusing on the amount of time spent in work or on one’s private life, on the satisfaction derived from time spent in each domain, and on the importance attributed by individuals to each of these two roles [

49]. Some authors have argued that the definitions of WLB adopted so far do not take into account developments in the personal sphere, in work contexts, and in relations between employees [

50]. In a recent publication [

51], the limits and prejudices related to the tendency to separate work from other spheres of life were highlighted, underlining the urgency of obtaining a broader view of this topic that is in step with the present times. Meanwhile, Lewis and Beauregard [

52] provided an overview of definitions of WLB, integrating two literature streams—namely, work-family interface research and critical management and organizational studies. The modern concept of WLB is the result of a research evolution that has taken place in this field, attempting to respond over time to socio-economic and workplace developments [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Scientific research on the topic of WLB has intensified since the early 1990s; at present, there is a wide variety of approaches to this topic, with various definitions and different analysis perspectives having been proposed [

57,

58,

59,

60]. A significant proportion of the literature has focused on WLB perception, considering the perspectives of owners, employees, and managers [

61,

62] as well as gender issues [

63,

64,

65,

66].

From some of the most recent literature reviews in this area, interesting insights into how the WLB concept has evolved over time have emerged with respect to different contexts. Rashmi and Kataria [

67] provided a systematic review of the literature focusing on WLB based on a bibliometric analysis; this shed light on emerging research themes such as flexible work arrangements, gender differences in WLB, the work-life interface and its related concepts, and WLB policies and practices, underlining the lack of a knowledge structure in the literature for this issue. Sirgy and Lee [

68] pointed out the need for an integrative framework for WLB literature reviews, which would allow problems related to the holistic concept of WLB to be overcome, thus enabling its dimensions, antecedents, moderators, mediators, and consequences to be identified. The relationship between WLB and work engagement was considered in one literature review that explored its various antecedents, mediators, and moderators [

69]. Another section of the literature has highlighted the correlation between WLB and other organizational variables, such as corporate performance and policies [

70,

71], while work-life concerns from the point of view of enrichment and depletion were addressed in [

72]. The literature has not neglected to consider the “dark side” of WLB, in some cases associating the work-family backlash with WLB policies [

73].

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many companies around the world to WFH. This affected employees’ WLB, leading to both positive outcomes by increasing organizational productivity [

74] and negative impacts, given the numerous challenges experienced by workers [

75]. The global pandemic also shed light on how men and women managed change, showing their different strategies for dividing their time between work and family in WFH situations [

76,

77] and trying to avoid gender inequalities in the distribution of duties and responsibilities [

78]. Employees, even the youngest and most accustomed to technology, were forced to develop new skills to allow smart working, sometimes without strong support from e-training and e-leadership programs [

79].

WLB has also been addressed with reference to the banking sector. Recent studies have dealt with WLB in commercial banks [

80,

81], some focusing on public sector banks [

82] or gender issues [

83,

84,

85]; others have considered the impacts of changes in working systems in the banking sector [

86], the impacts of psychological well-being and satisfaction with coworkers on the WLB/JP relationship [

18], and the role of employee assistance and leave programs [

87].

4. Job Performance

Job performance (JP) can be defined as the “total expected value to the organization of the discrete behavioral episodes that an individual carries out over a standard period of time” [

88] (p. 39). The state-of-the-art research on JP research highlights a proliferation of theoretical and empirical studies on JP predictors, including: employees’ ability, especially in entry-level jobs [

89]; psychological well-being and job satisfaction [

90]; employee engagement [

91,

92]; work stressors and coworker support [

93]; ability and non-ability [

94]; emotional and cognitive intelligence [

95,

96]; and cognitive reflection [

97].

The relationship between JP and the age of employees has been widely discussed in the literature. Some authors have compared older employees’ performance with younger employees [

98], while others have considered the relationship between employee age and JP, distinguishing professionals and non-professionals [

99]. Scholars have also addressed the relationship between workers’ age and JP, including some of the ten JP dimensions, such as organizational citizenship behaviors, safety performance, general counterproductive work behaviors, and aggression in the workplace [

100]. Another part of the JP literature has explored the mediating effect of resistance to change on the relationship between age and JP [

101]. The relationship between JP and gender has also been analyzed in studies that found gender-based differences in performance [

102] and differences in gender proportionality [

103].

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the JP of employees in organizations from different sectors, particularly during WFH [

104,

105]. Team interactions during the pandemic period, both internal and external to the organization, were investigated in one study [

106], as was the association between perceived stress, psychological distress, and job performance [

107].

The JP of bank employees has also been addressed in the literature. The effects on JP of several variables, such as organizational commitment [

108], training and work experience [

109], and nonwork and personal resources [

110], have been analyzed. Recently, the JP of bank employees has been linked with competitive intelligence [

111], work-family conflicts [

112], and emotional intelligence [

113].