Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Nutrition & Dietetics

Mangroves are halophile plants with vital economic and ecological services. Some mangrove fruits are edible and contain treasury compounds with ethnomedicinal properties. The levels of primary metabolites such as carbohydrates, protein, and fat within mangrove fruit are acceptable for daily intake. The mangrove fruits are rich in phenolic compounds, limonoids, and their derivatives, as the compounds show antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant activity.

- mangrove fruit

- secondary metabolites

- nutrition

1. Introduction

Prolonged drought and other natural disasters drive food shortages, and with the global COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years, global food distribution has been left in disarray. Disruption of the food supply and poverty cause inequity in accessing nutritious food stocks [1,2]. To the UN report, in 2021, up to 811 million of the world’s population is threatened by undernourishment, which represents an increase from previous years, whilst the production rate and economic aspect continue to disturb the food stock and distribution [3,4]. Those massive obstacles obstruct the sustainable development program adopted by the UN, especially point 2, to ensure sustainable manufacturer and consumption patterns to negate world hunger [5]. Thus, the search for emerging alternative food sources with a nutrition balance is requested [6]. Even though it is not a staple food for many populations, the consumption of fruit is steadily growing for its health benefit, the daily intake of which can be considered useful in providing nutrition supplementation [7]. Some types of mangroves produce edible fruit. Though it is not categorized as a commonly cultivated plant, the mangrove fruit for many communities is consumed for its ethnomedicinal properties.

Mangroves are halophile plants with vital economic and ecological services [8]. The area is considered the most productive ecosystem, underlying the fisheries’ food web [9]. Mangrove areas are wood/timber producers, feeding–nesting grounds for birds, and consumable fishery commodities such as fish and shellfish [10,11]. On the global scale, the mangrove area is a prominent natural contributor to managing the climate in complex ways, such as its carbon flux mechanism and sequestration scheme [12,13]. The mangrove area hides its useful function on a smaller scale, especially for human merit. The mangrove sediments are rich in nutrients due to the rapid decomposition of organic matters [14]. It holds financial worth up to USD 232.49 per hectare when transformed into fertilizer in the agroindustry sector [15,16]. However, the equilibrium between conservation and exploration is compulsory to contain the sustainability effort [17,18,19].

Various natural treasures are found, from deeply buried in the sediment to high up in the canopy within the mangrove forest. Many microorganisms as micro-producers reside within the ecosystem with their irreplaceable roles [20,21]. Mangrove plants are hosts for more than 850 fungi, while 38 are classified as endophytic symbionts [22]. Several associated bacteria are also well-recognized for synthesizing phytochemicals, such as compounds from Pseudoalteromonas xiamenensis for its antibiotic properties [23,24] and Streptomyces euryhalinus for its antioxidant properties [25]. Aside from the symbionts, all parts of mangroves have been used in folklore medicine since time immemorial [26]. The parts of Rhizophora mangle, Avicennia officinalis L., and Xylocarpus granatum J. Koenig are renowned for their pharmacological and ethnomedicinal usage [27,28,29]. Those bioactivities are assumed from the metabolite contents within the plant. Naphthofuranquinone with intense anti-trypanosomal activity is found in the twigs of A. lanata [30], while proanthocyanidins from leaves of Ceriops tagal show solid antioxidant activities [31]. Unfortunately, only 27 species of mangrove have been traditionally used [32]. The fruit is a seducing subject for exploration among parts of the mangrove. The fruit is known for its prowess in traditional medicine, such as treating asthma, bleeding, cough, febrifuge, hemorrhages, intestinal parasites, remedy piles, sprains, swelling, and ulcers [32]. Some mangrove fruits are also edible, assigning their compatibility to traditional food manufacturers with curative properties [33].

2. Nutrition Composition and Bioactivity of Mangrove Fruit Extract

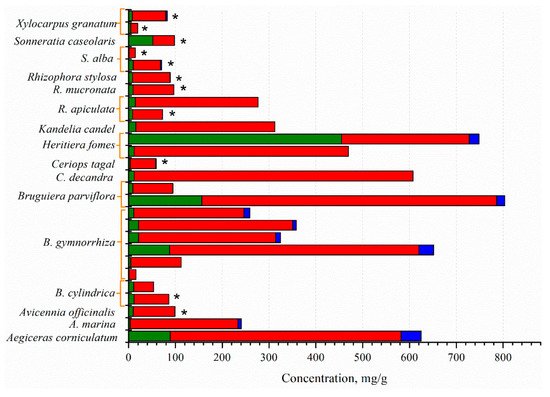

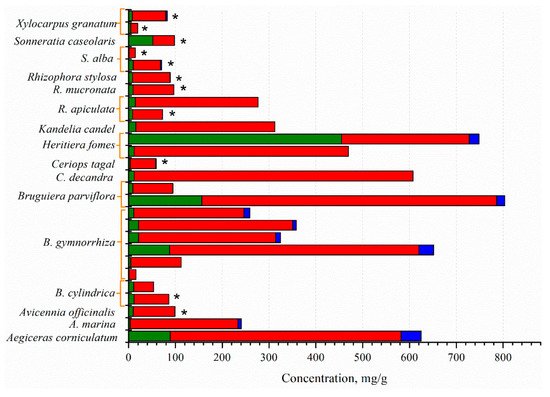

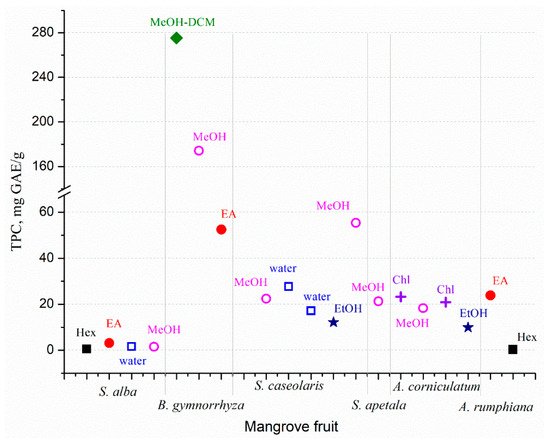

The mangrove fruit contains diverse nutrition compositions concerning the species. Carbohydrate is the dominant nutrition in all mangrove fruit, while the protein and fat contents vary (Figure 1). The total phenolic content (TPC) in the mangrove fruit is also widely investigated and, for most purposes, relates TPC with antioxidant activities [37,38]. TPC is positively correlated with the antioxidants; thus, the exploration probes for high TPC content in the fruit [39,40]. However, the evaluation is limited due to the extraction method (Figure 2), which may produce bias in the results. The TPC and other nutrient contents may be distinct among the fruit in the same species. Besides antioxidant activities, the mangrove fruit extract demonstrates other excellent bioactivities.

The molecular study of the fruit extract of A. officinalis revealed the potentiality of the extract in treating the worldwide emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Four compounds within the extract—methyl palminoleate, methyl linoleate, hexacosane, and triacontane—showed excellent binding affinity to the virus’ main proteases, such as Arg188, Cys145, Gln189, Glu166, and Met165 [44]. However, long clinical steps are still required to produce firm outcomes in administering the mangrove fruit extract to treat SARS-CoV-2.

The antibacterial activity of the mangrove extract comes from the synergistic relationship among secondary metabolites. The extract is rich in steroids, phenolic compounds, alkaloids, flavonoids, and other secondary metabolites. The enrichment of Artemia salina by extract of S. alba enhanced the resistance of giant tiger prawn against Vibrio harveyi. The enrichment of extract into A. salina escalates the steroid and phenol hydroquinone levels [45]. Alkaloid disrupts peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls, leading to the death of cells, while phenol affects the cytoplasmic membrane and breaks the cell nucleus. Flavonoids modify the cell protein and DNA, resulting in the inhibition of the growth of the cell [46].

Extract of mangrove fruit exhibited antimicrobial activities (Table 1) due to many phytochemicals, such as the total phenolic content, flavonoid [47], saponin, tannin, alkaloids, and saponin [48]. The composition of those phytochemicals varies based on the extraction method and solvent used. The composition determines the bioactivity; therefore, selecting extraction procedures is crucial in achieving noticeable positive results. The common antibacterial mechanism is attributed to membrane cell disruption [49]. Despite the antibacterial activity, the extract also exhibits antiviral properties. The aqueous extract of B. gymnorrhiza demonstrates potent inhibition of Zika virus (ZIKV) infection on human epithelial A549 cells by preventing the binding of the virus to the host cell surface. The aqueous extract contains polyphenols that disrupt the flavivirus's lipid membrane (outer membrane) [50]. The protein for the cell-binding receptor of ZIKV is targeted by cryptochlorogenic acid from the extract, leading to the virus’ death [51]. Moreover, the aqueous extract of R. mangle showed activity against various bacteria and depicted the cytotoxicity against human fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080 [52].

Various notable compounds are successfully identified from the extract of mangrove fruit. The eminent compound, such as (-)-17β-neriifolin, a cardiac glycoside, is found in the extract of Cerbera manghas with excellent heart stimulation function, effective in curing acute heart failure, at the same time show antiestrogenic, antiproliferative, and anticancer activities [55]. The fruit of B. gymnorrhiza contains isopimaradiene and 4-(2-aminopropyl) phenol. Isopimeradiene acts as antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial while 4-(2-aminopropyl) phenol shows high ROS scavenging activity, O2 scavenger, NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) stimulant, down-regulated cyclooxygenase-2 expression, and lowering of the nitrite level [38].

The administration of the mangrove fruit extract to animal models presents multiple vantages such as antioxidant [56], anti-atherosclerosis [57], antimicrobial [47,58], anti-diabetes [59], and hepatoprotective properties [60]. Excessive free-radical levels of diabetes trigger other diseases due to oxidative stress. Synthetic antioxidants are usually administered to reduce the oxidant level in the human body; however, side effects such as carcinogenicity should be addressed [61]. Mangrove fruit is a source of bioactive compounds with antioxidant activities. The antioxidant activity of the fruit is commonly related to the high content of vitamin C, anthocyanins, flavonoids, and polyphenols, which have hydrogen donating capabilities against free radicals such as nitric oxide (NO) [56]. The administration of methanol extract of the fruit of S. apetala to Long–Evans male rats inhibits the nitrite production in a dose-dependent manner. The extract acts as an insulin-like compound and modifies glucose utilization, enhances the transport of blood glucose to peripheral tissue, and stimulates the regeneration of the pancreas’ cells [40].

Table 1. The antimicrobial activities of fruit extract from different types of mangrove species.

| Species | Solvent | Antimicrobial | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avicennia marina | Ethanol | Aspergillus fumigatus | [58] |

| Candida albicans | |||

| A. officinalis | Methanol | Escherichia coli | [47] |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | |||

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| Streptococcus pyogenes | |||

| B. gymnorrhiza | Methanol | E. coli | [51] |

| P. aeruginosa | |||

| K. pneumoniae | |||

| S. aureus | |||

| Salmonella enteritidis | |||

| Sarcina lutea | |||

| Proteus mirabilis | |||

| Bacillus cereus | |||

| C. albicans | |||

| R. mangle | Ethanol | Enterococcus faecalis | [52] |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | |||

| Bacillus cereus | |||

| Streptococcus lactis | |||

| S. aureus | |||

| S. apetala | Methanol | E. coli | [40] |

| E. faecalis | |||

| Pseudomonas sp. | |||

| Shigella flexneri | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | |||

| S. caseolaris | Ethyl acetate | E. coli | [48] |

| C. albicans | |||

| Ethanol | E. coli | ||

| S. aureus | |||

| C. albicans | |||

| Methanol | S. aureus | [49,62] | |

| E. coli | |||

| C. albicans | |||

| P. aeruginosa | |||

| Acenobacter baumannii | |||

| Methanol:ethanol | E. coli | [63] | |

| Klebsiella sp. | |||

| Shigella boydii | |||

| S. sonnei | |||

| S. aureus | |||

| X. mekongensis | Methanol:ethanol | S. aureus | [63] |

The ethanolic extract of S. apetala shows anti-atherosclerosis in the male Wistar rat model [57]. The cholesterol levels, including LDL and HDL, are higher, and the formed foam is lower than the control animal [57]. Atherosclerosis is a vascular inflammatory disease characterized by lipid accumulation, fibrosis, and cell death in the arteries. The inflammation is mainly caused by high free-radical concentration ensuing in the incline of plasma lipid levels, such as LDL. LDL infiltrates the vascular sub-endothelium via impaired endothelium, which excites the oxidation process [64]. The oxidized LDL activates the endothelial cells expressed by leukocyte adhesion molecules such as vascular cell-adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) on the surface of the artery. The elevated oxidized LDL stimulates the production of ROS via nitric oxide activation. Typically, NO is a protective substance produced by the vascular endothelial cells; however, it enables pro-atherogenesis if produced by macrophages. Moreover, excessive ROS generation stimulates and activates Nf-kB p65 translocation, increasing the expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) and releasing the pro-inflammatory mediators by macrophages. Monocyte turns phagocytosis and macrophages of oxidized LDL to form foam cells [65,66,67]. Regarding its antioxidant property, the mangrove fruit extract prevents the excessive production of free radicals at the beginning of the mechanism [64].

The administration of the ethyl acetate extract of mangrove fruit X. moluccensi presented antidiabetic properties in a male albino Sprague–Dawley rat model; many blood parameters such as the blood glucose, serum fructosamine, serum triglycerides, and serum cholesterol levels declined. The extract improves phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase in the liver and kidneys while maintaining body weight [59]. The fruit of S. apetala displays hepatoprotective properties of male Kunming mice. The fruit extract’s antioxidative property improves the aspartate aminotransferase level in serum, reduces the alanine aminotransferase, and increases the survival rate. The hepatoprotective ability of the fruit extract in the liver is depicted by the incline in total antioxidant capacity and catalase, improvement in glutathione peroxidase and glutathione, and inhibition of myeloperoxidase, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor-α. The antioxidant properties of the fruit extract are suspected to prevent liver damage caused by oxidative stress from ROS [60].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/md20050303

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!

Figure 2. Total phenolic content (TPC) from several mangrove fruit extracted using different solvents: Hex (hexane), EA (ethyl acetate), water, MeOH (methanol), DCM (dichloromethane), EtOH (ethanol), and Chl (chloroform). Modified from [

Figure 2. Total phenolic content (TPC) from several mangrove fruit extracted using different solvents: Hex (hexane), EA (ethyl acetate), water, MeOH (methanol), DCM (dichloromethane), EtOH (ethanol), and Chl (chloroform). Modified from [