Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Horticulture

The word “pest” can be interpreted in many ways, ranging from something that causes minor personal irritation to something that results in major economic losses. The various insects that are referred to as thrips are used to discuss the question “what is a pest”. The diversity in biology among species of thrips is discussed here of their respective families and subfamilies, emphasising that pest behaviour is found in relatively few species of the insect Order Thysanoptera.

- pest thrips species

- Thripinae

- Frankliniella

- Thrips

1. Introduction

“What is a pest?” seems a particularly simple question. Yet, a simple reply is difficult to construct, because the concept of “pest” is itself a complex socio-economic problem. It involves human perceptions and behaviour, the food production systems as well as the health of our differing societies, and the biogeographic differences in natural and human-made ecosystems. Any definition of “pest” will range from an organism that causes serious economic damage, to an organism that is merely unwelcome at some particular place. This latter definition is by no means unreasonable when we consider the activities of thrips, the members of the insect Order Thysanoptera. These insects commonly display thigmotactic behaviour, with the adults crawling into enclosed spaces such that the maximum area of their body surface is in contact with their surroundings. A typical example is Limothrips cerealium, a species known as the Thunder Fly in Britain due to its habit of taking flight from its grass host plants in vast numbers when a summer storm approaches [1]. These thrips swarms may then enter and activate smoke detector fire alarms, causing distress particularly to staff in hospitals. Similar thigmotactic behaviour by Haplothrips victoriensis in southern Australia can result in these insects hiding in the central cavity of freshly harvested raspberries; this thrips does not feed on or damage the crop, but its presence within the fruit is clearly unwelcome. Similarly, the bean thrips of California, Caliothrips fasciatus, crawls into the navels of oranges where it is regarded as a quarantine risk by countries importing the fruit [2]. In some warmer countries the leaves of Ficus trees are often galled by Gynaikothrips ficorum. These large thrips fly around and sometimes fall into a glass of wine or beer held by someone relaxing beneath the shady trees—that person would certainly consider that particular thrips a pest. Thus, the statement by Lewis [3] that “Several hundred species of thrips are pests” depends on how the word “pest” is interpreted. The researchers focus the concept of “pest” on those thrips species for which they have reason to believe they are associated repeatedly with serious damage to cultivated plants (Table 1).

2. Assessing the Pest Status of Thrips

The published literature about thrips commonly involves an assumption that any thrips found on a cultivated plant will be a pest. This assumption can occur even in the absence of any evidence of damage, let alone crop loss or economic impact. One example, also mentioned below, is the Black Plague thrips in Australia (Figure 1A) that disperses from its grass host plants as these dry in summer; vast numbers then land on irrigated crops where they do not breed. Mass flights also occur in Thrips australis, a species that breeds primarily in the flowers of Eucalyptus trees that commonly have mass-flowering periods. All of the flowers on a single tree thus die within a short period, and the adult thrips then disperse in very large numbers, seeking shelter in the flowers of many different surrounding plants but without breeding in them. This phenomenon of massed flights of adults occurs in other thrips species but again, it is not necessarily associated with any damage to the plants (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Aggregations of adult thrips. (A) Black Plague Thrips (Haplothrips froggatti) on cotton bud. (B) Thrips parvispinus on garden Lily flower.

Even when some cultivated plant shows symptoms of thrips feeding damage, the culprit pest is not necessarily the most visible or abundant species. For example, a severely damaged crop of Solanum melongena in Brazil was observed to bear large numbers of the highly visible and dark species, Caliothrips phaseoli, but the leaf damage to the plants was due to small numbers of the small pale species, Thrips palmi [4]. Additionally, economically significant damage can occur on some sensitive fruit crops with remarkably low thrips populations. Even a single larva of Frankliniella occidentalis feeding under the sepals on a young nectarine (Prunus persica) may cause undesirable skin blemishes as that fruit expands.

Any attempt at a broad definition of pest must consider that “pest” is not an essential attribute of any thrips species. A species that is associated with crop damage at one site does not necessarily cause damage at some other site. Additionally, “crop damage” itself can vary from trivial markings on leaves to crop failure and economic losses. For example, Anaphothrips obscurus and A. sudanensis sometimes occur at some localities in sufficiently large numbers to cause visible leaf damage to cereal crops, but more commonly the populations of these thrips are inconspicuous and not associated with any visible damage. Other thrips species that are listed as pests have restricted distributions and thus have a relatively local economic impact; for example. Bradinothrips musae on banana trees in Brazil [11], or Ceratothripoides claratris as a virus vector on tomatoes in parts of southeast Asia [12]. At the opposite extreme there are polyphagous species such as Frankliniella occidentalis and Thrips tabaci whose feeding and virus vectoring have come to involve serious economic losses worldwide [13]. It is among these, and similar highly polyphagous species, that the most important thrips pests have developed.

3. The Diversity of Pest Thysanoptera

About 6300 thrips species are currently recognized [14], and these are considered to be members of one or other of the two Thysanoptera Suborders, the Terebrantia and the Tubulifera. The latter comprises 65% of all Thysanoptera species, and these are placed in the single family Phlaeothripidae. Remarkably few of the 3800 species in this family can be considered pests, with the majority of the species feeding only on fungi [15] on dead leaves and branches; these species may even be beneficial in facilitating nutrient recycling. Relatively few Phlaeothripidae species live and breed in flowers, the others are found feeding on green leaves where they often cause leaf distortions or even galls. Such species are usually limited to feeding on a single species of host plant, thus there are particular species of Phlaeothripidae causing leaf damage to persimmon trees (Diospyros kaki) in Japan, to Olive trees (Olea europaea) in southern Europe, and to cultivated Guarana trees (Paullinia cupana) in South America [21]. Severe leaf damage has been recorded on Hawaii leading to the death of the endemic plant Myoporum sandwichense by the introduced Australian phlaeothripid Klambothrips myopori [23].

The Thysanoptera Suborder Terebrantia comprises eight families [14], and the majority of pestiferous thrips are members of the single family Thripidae. It is only within this family that the vectors of Orthotospoviruses are known, and these vector species are the thrips that cause the greatest economic damage worldwide. Indeed, the major thrips pests are all members of the Thripinae, the largest of the four subfamilies recognized in the Thripidae. Each of the other three subfamilies, Panchaetothripinae, Dendrothripinae and Sericothripinae, includes a few pest thrips, but with only one species known as a virus vector.

4. Pestiferous Panchaetothripinae

The 150 species of this subfamily typically breed on older leaves rather than on newly emerged leaves, and not in flowers. The most well-known is the Greenhouse Thrips, Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis. First described from Europe, but native to South America [11,24], this thrips is now found throughout the world. In cool climates, it is usually found only in sheltered conditions, but in warmer climates it breeds readily out of doors. All life-stages of this species live on mature leaves, and affected leaves usually bear dark spots of faecal material that have been exuded by the larvae. Several species of the genus Helionothrips are similar in appearance and biology to Heliothrips species, with H. aino forming large populations on Taro (Colocasia esculenta), and H. annosus similarly on Cinnamomum burmanii. The red-banded cacao thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus, also Retithrips syriacus, commonly damage the leaves of various plants in tropical countries, ranging from cocoa to roses. The genus Hercinothrips includes at least three species that are associated with damaged leaves: H. bicinctus and H. femoralis both develop large populations on the older leaves of a wide range of plants; and H. dimidiatus has recently become a pest in southern Europe on decorative Aloe plants [26].

5. Pestiferous Dendrothripinae

Just over 100 species are known in this group, and they all feed and breed primarily on mature leaves rather than on young newly emerged leaves. Almost any of them may, at times, be associated with feeding symptoms, but very few are known to cause serious damage. Dendrothrips ornatus sometimes causes pale markings on the leaves of Privet (Ligustrum vulgare) in Europe, as well as similar symptoms on Lilac (Syringa vulgaris), a related member of the Oleaceae [27], in northern China. However, the only crop reported to be seriously damaged by a Dendrothrips species is Camellia sinensis in China, where D. minowai usually develops large populations. Two species of Pseudodendrothrips are also recorded in association with leaf damage: P. mori can be particularly serious on mulberry (Morus alba) in dry climates [28], but P. stuardoi seems to be less damaging on fig trees (Ficus carica) [29].

6. Pestiferous Sericothripinae

This subfamily currently comprises only three genera, with a total of 170 species [14], but only a few species in the genus Neohydatothrips have been associated with damage to any plants. The most important one, N. variabilis, is the main vector of soybean vein necrosis virus across much of North America [31]. This is the only Orthotospovirus known to be vectored by any thrips species that is not a member of the Thripinae. Considering the widespread cultivation around the world of soybean (Glycine max), this combination of thrips and virus has the potential of becoming of major economic importance. In Colombia, N. burungae (often under the name signifer) has been reported as damaging Passion fruit vines (Passiflora edulis) [32], and in southern China, N. flavicingulus has been found in large numbers damaging the leaves of Camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora). The marigold thrips, N. samayunkur, occurs widely around the world inducing damage to the leaves and flowers of garden plants in the genus Tagetes [33,34]. The only other sericothripine species that has an impact on the human economy is Sericothrips staphylinus, a species that has been used in the biological control of Gorse (Ulex europea), an invasive weed in several countries [35].

7. Pestiferous Thripinae

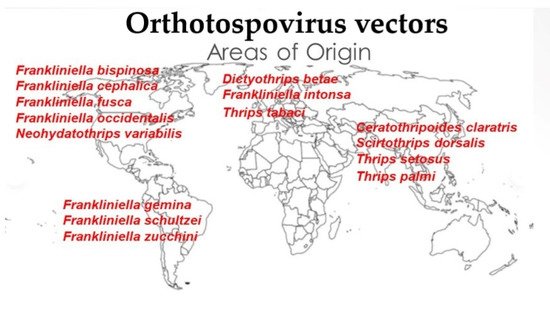

In considering the pest status among the 1800 known species in this subfamily it is important to emphasise that less than 1% of these species are recorded as vectors of the serious crop diseases known as Orthotospoviruses [36]. With the exception of Neohydatothrips variabilis in the Sericothripinae, the other 14 species recorded as vectors of this group of plant viruses are all members of the Thripinae, and these species are members of five different genera (Figure 2). Eight vector species are members of the genus Frankliniella: three are members of the genus Thrips; the remaining three are each placed in different unrelated genera. This suggests that the association between thrips and the various Orthotospovirus species has arisen independently several times and on different continents. Zhang et al. [36], in recognizing 30 species of Orthotospovirus stated that 17 of these are reported from China (including undescribed species). However, no known vector species is endemic to China, although Thrips palmi is possibly native in the tropical southwest of that country. In contrast, eight of the 15 thrips vector species are originally from the American continent, with five from North America, and three from South America (Figure 2). Although at least 90 species of Thripinae have been listed as pestiferous, globally, the greatest impact by thrips on crop production and profitability is by the Western Flower Thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis), the Melon Thrips (Thrips palmi) and the Onion Thrips (Thrips tabaci). The other pests, although often causing severe damage and losses, tend to be more local in their severity, such as Scirtothrips aurantii in South Africa, and Scirtothrips citri in California. Similarly several species of Megalurothrips are important pests of bean crops in tropical countries, Mycterothrips glycines causes leaf damage to crops of soy beans (Glycine max) in parts of Asia, and an Australian species, Pezothrips kellyanus, causes damage to citrus fruits in Australia, New Zealand and the European Mediterranean area.

Figure 2. Geographical origins of Orthotospovirus vector species.

8. Discussion

Given the right conditions, any phytophagous Thysanoptera species may develop locally a particularly large population and cause visible damage to some part of a plant. However, there is a considerable economic difference between the markings on a few leaves of Ligustrum due to the feeding of Dendrothrips ornatus, and the defoliation of a valuable crop of Solanum melongena by a population of Thrips palmi. It is the loss of income to a cultivator, whether through yield reduction or through quality reduction, that is the ultimate criterion of pest status. However, this is not a simple quality of a particular thrips species; it involves many variables other than the variation in the biology and behaviour of a pest thrips across its range. Thrips tabaci can be a serious pest on onions, but it occurs widely across Australia (and other places) on many different plant species on which it is rarely any problem. Similarly, Danothrips trifasciatus, Chaetanaphothrips orchidii, and C. signipennis are all recorded in various parts of the world as damaging plants as different as bananas, citrus and orchids, but each of these species is more commonly found in low numbers. In Brazil, Frankliniella schultzei is considered a major pest, whereas in China this species is not listed as a serious pest. Moreover, thrips populations can be remarkably unstable, with great variation in numbers from year to year, and this unpredictability of populations seems to be inherent among Thysanoptera.

Population size and economic damage by thrips species are thus essentially unpredictable in time, space and crop. Different parts of the world often cultivate different crops and also have a different native thrips fauna, and as a result the species recorded as pests also differ, with Brazil and China sharing only 11 widespread pest thrips. However, in addition to faunal differences, human perceptions and socio-economic expectations in crop production are likely to produce differing views on “pest damage”. Based on their individual experiences and commercial expectations, different observers will come to different conclusions as to what constitutes a pest. As with any human activity, some growers within the horticultural industry are clearly more skillful than others, often deploying a range of practices from careful selection of seedlings and planting date, to good quarantine and weed control. Such growers may produce a profitable crop requiring minimal use of chemical pest control. In contrast, a neighbouring grower may be persuaded by agricultural salesmen that the easiest approach to cultivation is to use large quantities of chemicals. Understanding such differences in human behaviour can, at times, be equally as important as establishing the pestiferous nature of a particular thrips species. For growers, it is thus best practice to approach each pest thrips situation individually, considering the biology of that particular species on that particular crop. The alternative extreme, a semi-industrial approach with a predetermined programme of pesticide spraying, carries the risk of inducing pesticide resistance and of population resurgence

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/insects13010061

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!