Livelihood refers to a systematic procedure of making a living on the basis of skills, resources, and feasible activities. With a view to resolving the problem of the sustainability of farmers’ livelihoods, the livelihood safety and quality of farmers in poor areas is considered a primary issue, as well as a key research hotspot for experts and scholars. In order to fundamentally help rural areas out of poverty and comprehensively promote rural revitalization, the government needs to not only offer policy support from all aspects, but also to fundamentally improve the livelihood ability of farmers themselves, enrich their livelihood strategies, and help them retain a sustainable way of living.

- livelihood capital

- livelihood strategy

- farmers

- logistic regression analysis

1. Introduction

2. Livelihood Capital, Livelihood strategy and The Impact of Livelihood Capital on Livelihood Strategies

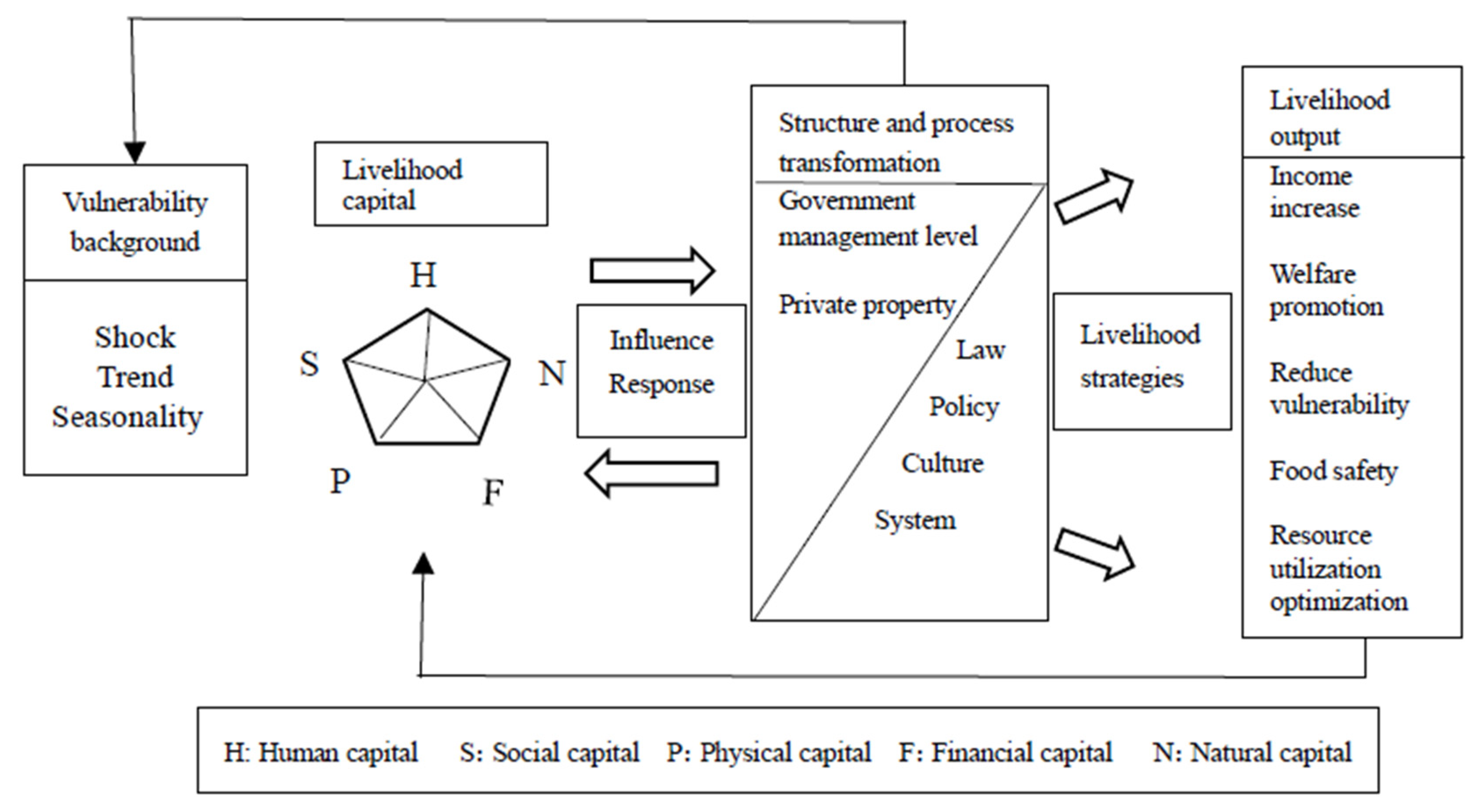

3. Sustainable Livelihood Theory

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14094955

References

- Wang, X.G. Rural households’ livelihood transition induced by land use change for tourism development: A case study of Jinshitan, Dalian. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 13, 4–14.

- Yan, H.; Bun, K.H.; Siyuan, X. Rural revitalization, scholars, and the dynamics of the collective future in China. J. Peasant. Stud. 2021, 48, 853–874.

- Liu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Y. China’s rural revitalization and development: Theory, technology and management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942.

- Zhang, L.; Liao, C.; Zhang, H.; Hua, X. Multilevel modeling of rural livelihood strategies from peasant to village level in Henan Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2967.

- Yang, X.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood adaptation of rural households under livelihood stress: Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 506.

- Tong, Y.; Shu, B.; Piotrowski, M. Migration, livelihood strategies, and agricultural outcomes: A gender study in rural China. Rural. Sociol. 2019, 84, 591–621.

- Kuang, F.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Wan, X.; Ning, J. Influence of livelihood capital on adaptation strategies: Evidence from rural households in Wushen Banner, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104228.

- Wu, B.; Liu, L. Social capital for rural revitalization in China: A critical evaluation on the government’s new countryside programme in Chengdu. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104268.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379.

- Guo, S.; Liu, S.; Peng, L.; Wang, H. The impact of severe natural disasters on the livelihoods of farmers in mountainous areas: A case study of Qingping Township, Mianzhu city. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 1679–1696.

- Perz, S.G.; Leite, F.L.; Griffin, L.N.; Hoelle, J.; Rosero, M.; Carvalho, L.A.; Castillo, J.; Rojas, D. Trans-boundary infrastructure and changes in rural livelihood diversity in the southwestern amazon: Resilience and inequality. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2807.

- Biggs, E.M.; Watmough, G.R. A community mmevel assessment of factors affecting livelihoods in nawalparasi district, nepal. J. Int. Dev. 2012, 24, 255–263.

- Liu, M.Y.; Feng, X.L.; Wang, S.G.; Zhong, Y. Does poverty-alleviation-based industry development improve farmers’ livelihood capital? J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 915–926.

- Erenstein, O.; Hellin, J.; Chandna, P. Poverty mapping based on livelihood assets: A meso-level application in the Indo-Gangetic Plains, India. Appl. Geogr. 2010, 30, 112–125.

- Fang, Y.P.; Fan, J.; Shen, M.Y.; Song, M.Q. Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital in mountain areas: Empirical analysis based on different settlements in the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 38, 225–235.

- Oladele, I.; Ward, L. Effect of micro-agricultural financial institutions of south Africa financial services on livelihood capital of beneficiaries in north west province south Africa. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 45.

- Johnson, S. Sustainable livelihoods and pro-poor market development. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2012, 20, 333–335.

- Masterman-Smith, H.; Rafferty, J.; Dunphy, J.; Laird, S.G. The emerging field of rural environmental justice studies in Australia: Reflections from an environmental community engagement program. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 359–368.

- Nielsen, Ø.J.; Rayamajhi, S.; Uberhuaga, P.; Meilby, H.; Smith-Hall, C. Quantifying rural livelihood strategies in developing countries using an activity choice approach. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 57–71.

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Poudel, S. Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1344–1366.

- Ado, A.M.; Savadogo, P.; Abdoul-Azize, H.T. Livelihood strategies and household resilience to food insecurity: Insight from a farming community in Aguie district of Niger. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 747–761.

- Ayuttacorn, A. Social networks and the resilient livelihood strategies of Dara-ang women in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Geoforum 2019, 101, 28–37.

- Zhang, J.; Mishra, A.K.; Zhu, P. Identifying livelihood strategies and transitions in rural China: Is land holding an obstacle? Land Use Policy. 2019, 80, 107–117.

- Alemayehu, M.; Beuving, J.; Ruben, R. Risk preferences and farmers’ livelihood strategies: A case study from eastern Ethiopia. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 1369–1391.

- Manlosa, A.O.; Hanspach, J.; Schultner, J.; Dorresteijn, I.; Fischer, J. Livelihood strategies, capital assets, and food security in rural southwest Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 167–181.

- Ding, W.; Jimoh, S.O.; Hou, Y.; Hou, X.; Zhang, W. Influence of livelihood capitals on livelihood strategies of herdsmen in inner Mongolia, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3325.

- Meng, J.; Amrulla, L.Y.; Xiang, Y. Study on relationship between livelihood capital and livelihood strategy of farming and grazing households: A case of Uxin Banner in Ordos. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2013, 49, 321–328.

- Zinda, J.; Zhang, Z. Land tenure legacies, household life cycles, and livelihood strategies in upland China. Rural. Sociol. 2018, 83, 51–80.

- Milbourne, P. The geographies of poverty and welfare. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 158–171.

- Qiu, P.; Xu, S.; Xie, G.; Tang, B.; Hua, B.; Yu, L. Analysis of the ecological vulnerability of the western Hainan Island based on its landscape pattern and ecosystem sensitivity. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2007, 27, 1257–1264.