Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Heart diseases, including congenital heart disease (CHD) and cardiovascular disorders, are considered comorbidities that render a major mortality risk to COVID-19 patients and make the treatment procedure extremely challenging. CHDs and cardiovascular disorders increase the susceptibility to heart failure which is much increased in patients of COVID-19. Epigenetic perturbations through DNA methylation, histone modification, nc-RNA and so on, with alterations in transcriptome and proteome are reported in COVID-19 patients.

- COVID-19

- congenital heart defects

- cardiovascular disease

- physiology

- epigenetics

1. Cardiovascular Damage during SARS-CoV-2 Infection

COVID-19 patients show acute myocardial injury and chronic cardiovascular damage, which are conditions whose risks are increased by congenital heart disease (CHD). In order to protect against the above conditions during COVID-19 infection and treatment, the cardiovascular impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection needs to be well-reserched. This is because COVID-19 treatment becomes extremely inconvenient and complicated if patients have additional conditions such as myocardial damage which often lead to death. To make matters worse, acute cardiac injury is more prevalent in COVID-19 patients with fatal outcomes, while patients presenting cardiovascular risk factors are at supposedly increased risk of death from COVID-19 [1][2][3][4][5]. In this direction, several interesting observations have been reported as presented below.

It was showed that 36 COVID-19 patients in the ICU have significantly elevated levels of myocardial injury biomarkers such as median creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) and high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-cTnI) [6]. In COVID-19 patients, increased levels of hs-cTnlI correlated with a four-fold higher risk of fatality in patients despite COVID-19 treatment being adjusted for age and pre-existing cardiovascular disorders [1][7]. Patients reported heart palpitations and chest tightness, while many patients who died of COVID-19 had cardiac arrest during hospitalization [6][8]. In another, COVID-19 patients in the ICU showed cardiovascular complications such as elevated blood pressure, elevated cardiac biomarker levels in serum, and abnormalities detected by electrocardiography and echocardiography [9]. In the past, infection of SARS-CoV, from which SARS-CoV-2 is derived, has been reported to cause chronic cardiovascular damage in 44% of 25 patients [10]. It has also been shown that systemic symptoms and severe pneumonia are higher in SARS-CoV-2 patients above 60 years of age, which can predictably worsen due to underlying cardiovascular conditions [11].

Several were reporting COVID-19 fatalities and associated cardiovascular disease have presented that 15–70% of patients who had COVID-19-related deaths also had underlying cardiovascular disease [1][2][3][5]. This important observation calls for a focus on understanding whether any particular predisposition for COVID-19 patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disorders exists. This hypothesis is further supported by ones reporting probable connections among cardiovascular comorbidity and high severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection [2][12], and myocardial dysfunction in 20–30% of COVID-19 patients in ICU [4]. Moreover, fourteen different ones have reported the presence of a minimum of two cardiac biomarkers in COVID-19 under hospitalization [4].

Complications associated with blood coagulation factors have also been observed in COVID-19 patients. Abnormalities associated with higher risks of thromboembolism of both veins and arteries have been linked to COVID-19 patients [13][14]. Systemic thromboprophylaxis has been reported in COVID-19 patients among whom approximately 31% patients show thrombotic complications, where pulmonary embolism is projected as the primary cause of complications [15]. Other than pulmonary embolism, some of the other complications seen in COVID-19 patients include deep vein thrombosis, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral arterial thromboembolism. Several others have reported frequent events of venous and arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 patients, where 27–69% are for peripheral venous thromboembolism, approximately 79% for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism [16][17][18]. One of these reported 31% combined arterial and venous thrombosis in 184 patients at ICU having COVID-19 pneumonia although they show appropriate prophylactic anticoagulation [16].

In support of these observations, other studies have also reported a higher risk for venous thromboembolism during severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [19]. In this direction, it is on 143 COVID-19 patients presents lower extremity deep vein thrombosis in 46% patients, where these 46% patients show worse prognosis, increased cardiac injury, and mortality [14]. Further, autopsies have revealed pathological information implicating elevated risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients such as angiogenesis and severe endothelial injury angiogenesis [20][21].

At the molecular level, it has been identified that hemostasis-associated abnormalities in COVID-19 patients that include elevated levels of D-dimer and fibrin degradation entities, lengthened thrombin and prothrombin durations and international normalized ratio, reduced activated partial thromboplastin duration, positive antiphospholipid syndrome related antibodies, and thrombocytopenia coupled with traditional comorbidities [2][22][23][24][25].

The cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients causes extreme inflammation stress which likely leads to rapid inflammation in vascular tissue that leads to atherosclerosis, cardiac arrhythmia, and myocarditis [12]. It is speculated that the intense inflammation during COVID-19 makes patients prone to intravascular thrombosis which elevates levels of blood clotting factors. A predisposition of COVID-19 patients to thrombosis likely results from direct and indirect impacts of SARS-CoV-2 and processes associated with its infection such as severe inflammation, critical illness, and hypoxia [22]. The complications are exacerbated in combination with immobilization and pre-existing comorbidities which lead to venous thromboembolism [26]. It is ongoing to identify the detailed mechanisms that link COVID-19 and disrupted blood coagulation. Nonetheless, the collective observations from the above reports coupled with the fact that COVID-19 patients show a high frequency of ischemic stroke [27], indicate that vascular thrombosis is an integral part of COVID-19 [4].

2. Congenital Heart Disease

COVID-19 treatment is challenged in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) because CHDs are considered comorbidities for COVID-19 that increase mortality risk in patients. Hence, detailed connections between COVID-19 and CHDs need to be investigated to develop personalized therapies for COVID-19 patients with CHDs. In this direction, significant focus is required on CHDs.

CHDs are the most common congenital defect in newborn babies affecting 0.8% of live births, and includes abnormalities in the heart structure or great vessels which occur during the development of the fetus at pregnancy [28][29]. It is estimated that 1 in every 100 children has defects in the heart due to underlying genetic or chromosomal anomalies [28], 40% of which are diagnosed in the first year of life [30]. However, the true prevalence might be significantly higher. CHD is also the most prevalent cause of infant deaths from birth defects [29]. Risk factors include alcohol, drug and medicinal abuse during pregnancy, viral infections during the first trimester, maternal diabetes, obesity and other complications, and family history [28][29]. Outcomes vary with socio-demographic index, highlighting the important for introducing policies to address these global inequalities for optimum amelioration of the disease [31].

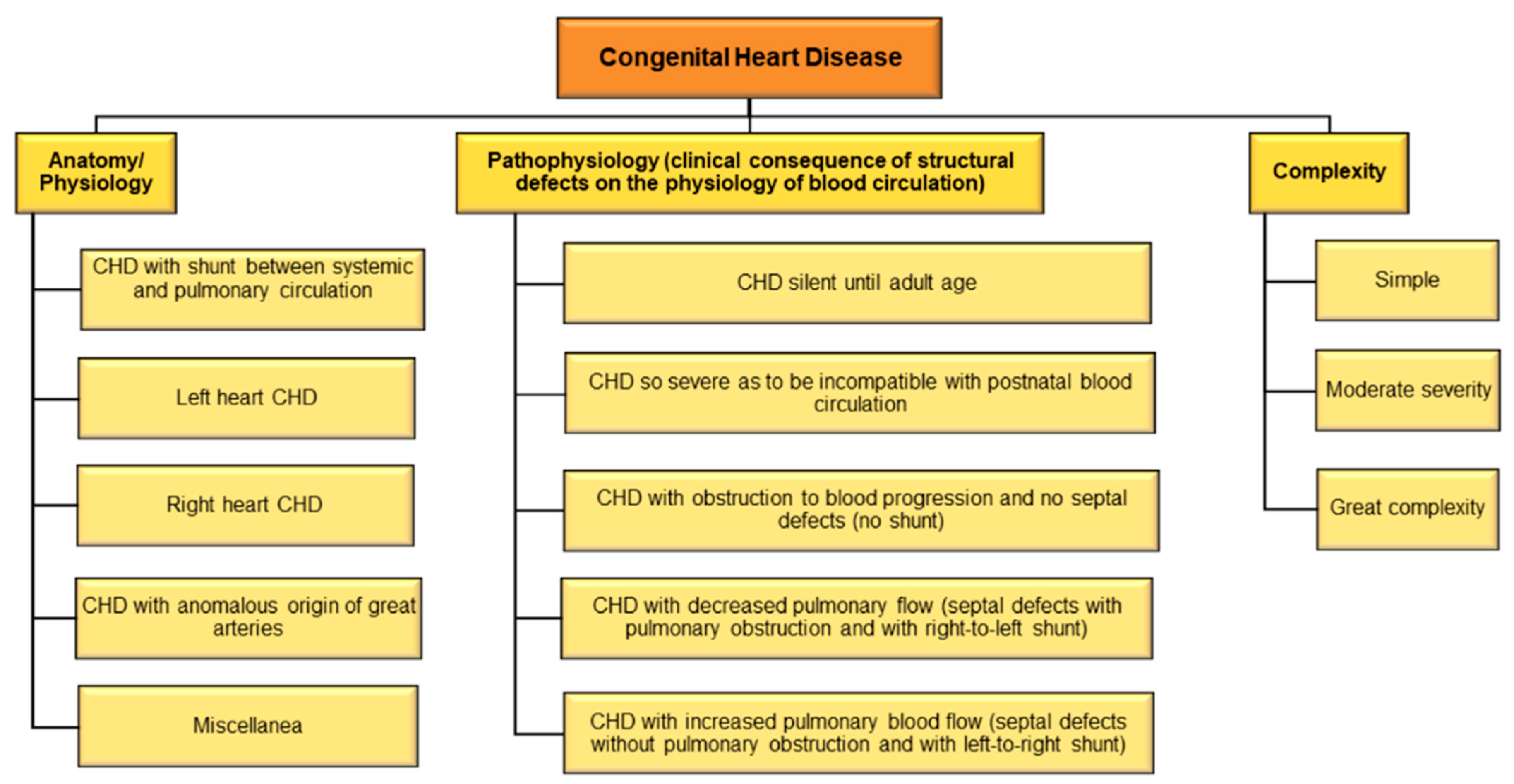

There are different types of CHD and consequently, different methods of disease classification (Figure 1). Considering the underlying anatomy and pathophysiology, CHD may be classified as (1) CHD with shunt between systemic and pulmonary circulation, (2) left heart CHD, (3) right heart CHD, (4) CHD with anomalous origin of great arteries, and (5) miscellanea [32]. Based on pathophysiology using clinical consequence of structural defects on the physiology of blood circulation, CHD may be classified as (1) CHD with increased pulmonary blood flow (septal defects without pulmonary obstruction and with left-to-right shunt); (2) CHD with decreased pulmonary flow (septal defects with pulmonary obstruction and with right-to-left shunt); (3) CHD with obstruction to blood progression and no septal defects (no shunt); (4) CHD so severe as to be incompatible with postnatal blood circulation; and (5) CHD silent until adult age [33].

Figure 1. Classification of CHD.

A useful and rapid method of classification categorizes CHD into CHD of great complexity, CHD of moderate severity, and simple CHD [29]. Recently it is also classified that adult CHD anatomic and physiological parameters to predict 15-year cardiac mortality [34]. The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPCCC) and the Eleventh Iteration of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) have devised standard codes for classifying CHD [35]. An older study had shown that ICD codes may lead to substantial misclassification of CHD [36]; however, recent studies to validate if newer classifications have been deemed effective are warranted.

3. Diagnosis of CHD

Recent advances in medical technology and diagnostics have facilitated in early detection of CDHs (Figure 2), though mortality, albeit decreasing, still remains unacceptably high [37]. Prenatal diagnosis using two-dimensional fetal echocardiography (ECG) was the conventional method of prenatal diagnosis of CHD; however, this has been replaced by contemporary three-dimensional and four-dimensional ECG over the past decade [37]. Other methods of detection include advanced ultrasound techniques, fetal magnetic resonance imaging, and fetal magnetocardiography [38]. Many have shown the accuracy of prenatal diagnosis using ECG [39][40][41][42][43]. However, all these methods have inherent limitations as to what can and cannot be detected and interpretated, not limited to imaging and anatomy, thereby necessitating novel methods of diagnosis [37][44].

Figure 2. Diagnosis and management of CHDs.

Recently, it was showed that magnetic resonance imaging, in combination with gene analysis using array comparative genome hybridization analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization could be a more effective diagnostic method for CDHs [45]. Similarly, molecular biomarkers too have shown considerable promise for use in prenatal diagnosis of CHD [46][47][48]. In addition to the above, detection of CHD neonates include clinical examinations, such as for congestive heart failure, a rhythm disturbance or heart murmur, cyanosis, and measurement of transcutaneous oxygen saturation [49][50]. Neonatal diagnosis has shown to be successful in detecting CHD and predicting outcomes [51]. Despite of all the advances in early detection of CHD, what remains unavoidable is the impact CHD diagnosis on parents, not limited to stress, uncertainty and other psychological turmoil [52][53][54], and the need for mental/social support to address such concerns [55][56].

4. CHD during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has put the global healthcare system on the edge and has severely affected the management of different acute and chronic diseases including CHD. COVID-19 patients have an increased risk of heart failure (Freaney 33,001,179), while patients with low LVEF (left ventricular ejection fraction), which is an indicator of heart failure, are associated with increased susceptibility to COVID-19 (33,205,916 Matsushita, 32,509,415 Sinkey). Cardiovascular abnormalities are reported on multiple COVID-19 patients (Grillet 32,324,103, Maham 32,437,313), and the list of complications includes tachycardia, non-obstructive coronary artery disease, and non-ischemic cardiac myopathy (Fried 32,243,205). Neuroimaging on 725 hospitalized COVID-19 patients revealed some on cardioembolism where the heart propels undesired entities to brain circulation resulting in stroke, as well as the presence of other cardiovascular abnormalities (Maham 32,437,313). Hence, the cardiovascular implications also extend to neurological dysfunctions. CHDs render patients more susceptible to heart failure and COVID-19 affects the cardiovascular system with symptoms often similar to those of CHDs. Therefore, distinguishing between the two might prove challenging [57]. Many children with COVID-19 are asymptomatic or have minimum symptoms; therefore, the magnitude of children with CHD and infected with COVID-19 is difficult to assess, as presented by Lewis et al. [58]. It was focused on COVID-19’s impact and predictors in patients with CHDs, but the number of symptomatic COVID-19 patients was low.

Nonetheless, it has significant clinical implications including the identification that if these patients have a genetic syndrome and if they are adults at an advanced stage of physiology, then their risk for moderate to severe COVID-19 infection is maximum [58]. It is reported that out of 53 COVID-19 patients with CHDs, 52 were symptomatic. CHDs in these patients include 16 cases or 30% patients showing tetralogy of Fallot or pulmonary stenosis, 10 cases of 19% patients showing single ventricle physiology status post Fontan palliation, and 6 cases or 11% patients showing shunting defects. Further, seven cases for each of the three conditions were seen: i. congenital valve abnormality, ii. atrioventricular canal defects, and iii. anomalous left and right coronary arteries, coarctation of the aorta, double-chamber right ventricle, pulmonary atresia, D-transposition, and congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries [58]. Lewis et al. have presented detailed analyses of these patients, where a key observation highlights that the duration of COVID-19 symptoms is longer in patients with ventricular dysfunction.

Moreover, although children are at low risk of mortality from COVID-19 and there are insufficient data on COVID-19 in children, experience with previous viral diseases, including influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, makes it reasonable to extrapolate that COVID-19 would severely affect children with CHD [57]. Furthermore, CHD is associated with a multitude of comorbidities and health complications, thereby heightening the risk of COVID-19 [59]. Infants and young children with CHD appear to be more susceptible to COVID-19 than older children with CHD, as shown by a handful ones [60]. Another describes a few of children with pre-existing CHD and infected with COVID-19. The children had adverse outcomes mostly due to exacerbation of their pre-existing conditions or missed COVID-19 symptoms due to their similarity with CHD symptoms [61].

Urgent invasive interventions, such as cardiac surgery to ameliorate CHD in newborns and infants, have proven especially challenging during the pandemic. The pandemic has stretched the healthcare infrastructure, and challenges in the face of CHD include looming resource scarcities of equipment, personnel, and blood, as well as infection risks in patients, caregivers, family members, and healthcare providers [62]. Wearing of masks and physical distancing for children is often an obstacle, and children mostly present as asymptomatic carries of COVID-19. Special attention to testing/screening of the patients and their families and routine use of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers is pertinent to limit spread COVID-19 in these vulnerable children with pre-existing CHDs [63] A Canadian one has brought to light the health management of children with CHD. These children are at risk of both COVID-19 disease and secondary cardiovascular outcomes due to limitations in physical activities imposed to control the pandemic. It has shown a drop in their physical activity during the pandemic, thereby highlighting future challenges for both the patients and the healthcare system in managing CHD [64].

5. Vaccination for Improving Outcomes in CHD

For the last few centuries, vaccination, especially prophylactic vaccination, undoubtedly remains the most effective means of preventing infectious diseases [65]. Not surprisingly, global vaccination as a prevention of COVID-19 has opened new avenues to COVID-19 prevention/management, yet poses many questions and challenges. Two mRNA-based vaccines, independently developed by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna [66][67], have already been authorized, pre-ordered, and are in the process of being administered in several countries including the US, Canada, and EU [68]. Each country has prioritized certain individuals for receiving COVID-19 vaccination including those at high risk of illness/mortality, those at high risk of exposure to the disease including essential workers, and those needing special benefits such as minority populations [69]. Needless to say, CHD patients will be prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination, as these patients are at a high risk of developing COVID-19 [59]. This assumption is an extrapolation from the standard of care for CDH, where vaccination from other respiratory viruses such as influenza virus and RSV have proven effective as previously elaborated. Therefore, COVID-19 vaccination ushers in new hope for children suffering doubly from CHD and an ongoing pandemic, both with no end in sight.

However, what is of concern is the equitability of global vaccine purchase and mobilization. Richer countries, accounting for only 13% of the global population, have already secured vaccine doses, leaving dwindling short-term supplies for low- and middle-income countries [68]. Variations in vaccine pricing and ultra-low handling and storage temperatures are other obstacles in equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines globally, with developing countries lacking sufficient infrastructure for the same. As the incidence of CHD in developing countries is relatively higher compared to developed countries [70], most children with CHD and their families/caregivers/healthcare system face unforeseen uncertainties and unprecedented challenges in CDH management in the era of the current pandemic.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/epigenomes6020013

References

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; Wang, H.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 811–818.

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062.

- Wang, L.; He, W.; Yu, X.; Hu, D.; Bao, M.; Liu, H.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 639–645.

- Khan, M.S.; Shahid, I.; Anker, S.D.; Solomon, S.D.; Vardeny, O.; Michos, E.D.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J. Cardiovascular implications of COVID-19 versus influenza infection: A review. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 403.

- Chen, T.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Yan, W.; Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Ma, K.; Xu, D.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. BMJ 2020, 368, m1091.

- Wang, D.; Hu, B.; Hu, C.; Zhu, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Xiang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020, 323, 1061–1069.

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; Gong, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 802–810.

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Xie, X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 259–260.

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506.

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Sun, X.; Yan, Z.; Hu, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Yin, P.; et al. Altered Lipid Metabolism in Recovered SARS Patients Twelve Years after Infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9110.

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Kok, K.H.; To, K.K.; Chu, H.; Yang, J.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Yip, C.C.; Poon, R.W.; et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020, 395, 514–523.

- Madjid, M.; Safavi-Naeini, P.; Solomon, S.D.; Vardeny, O. Potential Effects of Coronaviruses on the Cardiovascular System: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 831–840.

- Poggiali, E.; Bastoni, D.; Ioannilli, E.; Vercelli, A.; Magnacavallo, A. Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism: Two Complications of COVID-19 Pneumonia? Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2020, 7, 001646.

- Skeik, N.; Smith, J.E.; Patel, L.; Mirza, A.K.; Manunga, J.M.; Beddow, D. Risk and Management of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with COVID-19. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 73, 78–85.

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020, 395, 507–513.

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020, 191, 145–147.

- Llitjos, J.F.; Leclerc, M.; Chochois, C.; Monsallier, J.M.; Ramakers, M.; Auvray, M.; Merouani, K. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1743–1746.

- Nahum, J.; Morichau-Beauchant, T.; Daviaud, F.; Echegut, P.; Fichet, J.; Maillet, J.M.; Thierry, S. Venous Thrombosis Among Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2010478.

- Cui, S.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1421–1424.

- Lax, S.F.; Skok, K.; Zechner, P.; Kessler, H.H.; Kaufmann, N.; Koelblinger, C.; Vander, K.; Bargfrieder, U.; Trauner, M. Pulmonary Arterial Thrombosis in COVID-19 With Fatal Outcome: Results From a Prospective, Single-Center, Clinicopathologic Case Series. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 350–361.

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 120–128.

- Bikdeli, B.; Madhavan, M.V.; Jimenez, D.; Chuich, T.; Dreyfus, I.; Driggin, E.; Nigoghossian, C.; Ageno, W.; Madjid, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. COVID-19 and Thrombotic or Thromboembolic Disease: Implications for Prevention, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Follow-Up: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2950–2973.

- Skeik, N.; Mirza, A.; Manunga, J. Management of venous thromboembolism during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2020, 8, 897–898.

- Gao, Y.; Li, T.; Han, M.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 791–796.

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, S.; Xia, P.; Cao, W.; Jiang, W.; Chen, H.; Ding, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Coagulopathy and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e38.

- Tang, N.; Bai, H.; Chen, X.; Gong, J.; Li, D.; Sun, Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1094–1099.

- Merkler, A.E.; Parikh, N.S.; Mir, S.; Gupta, A.; Kamel, H.; Lin, E.; Lantos, J.; Schenck, E.J.; Goyal, P.; Bruce, S.S.; et al. Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs Patients With Influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1366–1372.

- Sun, R.; Liu, M.; Lu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, P. Congenital Heart Disease: Causes, Diagnosis, Symptoms, and Treatments. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 72, 857–860.

- Bouma, B.J.; Mulder, B.J. Changing Landscape of Congenital Heart Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 908–922.

- Pierpont, M.E.; Basson, C.T.; Benson, D.W., Jr.; Gelb, B.D.; Giglia, T.M.; Goldmuntz, E.; McGee, G.; Sable, C.A.; Srivastava, D.; Webb, C.L.; et al. Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: Current knowledge: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: Endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation 2007, 115, 3015–3038.

- Zimmerman, M.S.; Smith, A.G.C.; Sable, C.A.; Echko, M.M.; Wilner, L.B.; Olsen, H.E.; Atalay, H.T.; Awasthi, A.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Boucher, J.L.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 185–200.

- Micheletti, A. Congenital Heart Disease Classification, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. In Congenital Heart Disease; Flocco, S., Lillo, A., Dellafiore, F., Goossens, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–67.

- Thiene, G.; Frescura, C. Anatomical and pathophysiological classification of congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2010, 19, 259–274.

- Ombelet, F.; Goossens, E.; Van De Bruaene, A.; Budts, W.; Moons, P. Newly Developed Adult Congenital Heart Disease Anatomic and Physiological Classification: First Predictive Validity Evaluation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014988.

- Franklin, R.C.G.; Beland, M.J.; Colan, S.D.; Walters, H.L.; Aiello, V.D.; Anderson, R.H.; Bailliard, F.; Boris, J.R.; Cohen, M.S.; Gaynor, J.W.; et al. Nomenclature for congenital and paediatric cardiac disease: The International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPCCC) and the Eleventh Iteration of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Cardiol. Young 2017, 27, 1872–1938.

- Strickland, M.J.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.J.; Jacobs, J.P.; Reller, M.D.; Mahle, W.T.; Botto, L.D.; Tolbert, P.E.; Jacobs, M.L.; Lacour-Gayet, F.G.; Tchervenkov, C.I.; et al. The importance of nomenclature for congenital cardiac disease: Implications for research and evaluation. Cardiol. Young 2008, 18 (Suppl. 2), 92–100.

- Espinoza, J. Fetal MRI and prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects. Lancet 2019, 393, 1574–1576.

- Donofrio, M.T.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Copel, J.A.; Sklansky, M.S.; Abuhamad, A.; Cuneo, B.F.; Huhta, J.C.; Jonas, R.A.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 2183–2242.

- van Velzen, C.L.; Clur, S.A.; Rijlaarsdam, M.E.; Pajkrt, E.; Bax, C.J.; Hruda, J.; de Groot, C.J.; Blom, N.A.; Haak, M.C. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects: Accuracy and discrepancies in a multicenter cohort. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 47, 616–622.

- Qiu, X.; Weng, Z.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Ling, W.; Ma, H.; Huang, H.; Lin, Y. Prenatal diagnosis and pregnancy outcomes of 1492 fetuses with congenital heart disease: Role of multidisciplinary-joint consultation in prenatal diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7564.

- Lytzen, R.; Vejlstrup, N.; Bjerre, J.; Bjorn Petersen, O.; Leenskjold, S.; Keith Dodd, J.; Stener Jorgensen, F.; Sondergaard, L. The accuracy of prenatal diagnosis of major congenital heart disease is increasing. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 308–315.

- Rocha, L.A.; Araujo Junior, E.; Rolo, L.C.; Barros, F.S.; da Silva, K.P.; Leslie, A.T.; Nardozza, L.M.; Moron, A.F. Prenatal detection of congenital heart diseases: One-year survey performing a screening protocol in a single reference center in Brazil. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 175635.

- Letourneau, K.M.; Horne, D.; Soni, R.N.; McDonald, K.R.; Karlicki, F.C.; Fransoo, R.R. Advancing Prenatal Detection of Congenital Heart Disease: A Novel Screening Protocol Improves Early Diagnosis of Complex Congenital Heart Disease. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018, 37, 1073–1079.

- Sharland, G. Changing impact of fetal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997, 77, F1–F3.

- Wang, L.; Nie, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Bai, L.; Hua, T.; Wei, S. Use of magnetic resonance imaging combined with gene analysis for the diagnosis of fetal congenital heart disease. BMC Med. Imaging 2019, 19, 12.

- Wagner, R.; Tse, W.H.; Gosemann, J.H.; Lacher, M.; Keijzer, R. Prenatal maternal biomarkers for the early diagnosis of congenital malformations: A review. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 86, 560–566.

- Gu, M.; Zheng, A.; Tu, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Han, S.; Hu, X.; Zhu, J.; Pan, Y.; et al. Circulating LncRNAs as Novel, Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Prenatal Detection of Fetal Congenital Heart Defects. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 1459–1471.

- Smith, T.; Rajakaruna, C.; Caputo, M.; Emanueli, C. MicroRNAs in congenital heart disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015, 3, 333.

- Kardasevic, M.; Jovanovic, I.; Samardzic, J.P. Modern Strategy for Identification of Congenital Heart Defects in the Neonatal Period. Med. Arch. 2016, 70, 384–388.

- Benson, L.N.; Freedom, R.M. The Clinical Diagnostic Approach in Congenital Heart Disease. In Neonatal Heart Disease; Springer: London, UK, 1992; pp. 165–176.

- Wren, C.; Richmond, S.; Donaldson, L. Presentation of congenital heart disease in infancy: Implications for routine examination. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999, 80, F49–F53.

- Jackson, A.C. Managing Uncertainty in Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e204353.

- Harris, K.W.; Brelsford, K.M.; Kavanaugh-McHugh, A.; Clayton, E.W. Uncertainty of Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e204082.

- Biber, S.; Andonian, C.; Beckmann, J.; Ewert, P.; Freilinger, S.; Nagdyman, N.; Kaemmerer, H.; Oberhoffer, R.; Pieper, L.; Neidenbach, R.C. Current research status on the psychological situation of parents of children with congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9, S369–S376.

- David Vainberg, L.; Vardi, A.; Jacoby, R. The Experiences of Parents of Children Undergoing Surgery for Congenital Heart Defects: A Holistic Model of Care. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2666.

- Kolaitis, G.A.; Meentken, M.G.; Utens, E. Mental Health Problems in Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 102.

- Alsaied, T.; Aboulhosn, J.A.; Cotts, T.B.; Daniels, C.J.; Etheridge, S.P.; Feltes, T.F.; Gurvitz, M.Z.; Lewin, M.B.; Oster, M.E.; Saidi, A. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic Implications in Pediatric and Adult Congenital Heart Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017224.

- Lewis, M.J.; Anderson, B.R.; Fremed, M.; Argenio, M.; Krishnan, U.; Weller, R.; Levasseur, S.; Sommer, R.; Lytrivi, I.D.; Bacha, E.A.; et al. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Patients With Congenital Heart Disease Across the Lifespan: The Experience of an Academic Congenital Heart Disease Center in New York City. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017580.

- Magoon, R. COVID-19 and congenital heart disease: Cardiopulmonary interactions for the worse! Paediatr. Anaesth. 2020, 30, 1160–1161.

- Iacobazzi, D.; Baquedano, M.; Madeddu, P.; Caputo, M. COVID-19, State of the Adult and Pediatric Heart: From Myocardial Injury to Cardiac Effect of Potential Therapeutic Intervention. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 140.

- Simpson, M.; Collins, C.; Nash, D.B.; Panesar, L.E.; Oster, M.E. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection in Children with Pre-Existing Heart Disease. J. Pediatr. 2020, 227, 302–307.e2.

- Stephens, E.H.; Dearani, J.A.; Guleserian, K.J.; Overman, D.M.; Tweddell, J.S.; Backer, C.L.; Romano, J.C.; Bacha, E. COVID-19: Crisis management in congenital heart surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160, 522–528.

- Giordano, R.; Cantinotti, M. Congenital heart disease in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 69, 172–174.

- Hemphill, N.M.; Kuan, M.T.Y.; Harris, K.C. Reduced Physical Activity During COVID-19 Pandemic in Children With Congenital Heart Disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 1130–1134.

- Chang, K.P. Vaccination for Disease Prevention and Control: The Necessity of Renewed Emphasis and New Approaches. J. Immunol. Immunotech. 2014, 1.

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: Pfizer and BioNTech submit vaccine for US authorisation. BMJ 2020, 371, m4552.

- Callaway, E. COVID vaccine excitement builds as Moderna reports third positive result. Nature 2020, 587, 337–338.

- Mullard, A. How COVID vaccines are being divvied up around the world. Nature 2020, 30.

- Ismail, S.J.; Zhao, L.; Tunis, M.C.; Deeks, S.L.; Quach, C.; National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Key populations for early COVID-19 immunization: Preliminary guidance for policy. CMAJ 2020, 192, E1620–E1632.

- Wu, W.; He, J.; Shao, X. Incidence and mortality trend of congenital heart disease at the global, regional, and national level, 1990–2017. Medicine 2020, 99, e20593.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!