1. Introduction

The prevalence of chronic wounds is rising [

1,

2] and in developed countries the estimated lifetime risk is 1–2% predominately affecting the elderly population [

2,

3]. The terms “chronic” and “nonhealing” wounds are used interchangeably with no universally accepted definition for chronicity [

4]. Depending on the literature and the type of wound, the time span for chronicity is defined between 2 weeks to 3 months [

4,

5,

6]. The most common types of chronic wounds are vascular ulcers (venous or arterial), diabetic ulcers, and pressure ulcers present on the lower limbs [

4]. The ulcers are associated with immobility, stress, reduced quality of life, amputation, severe infection, death as well as high economic costs [

5,

7].

There is an increasing body of evidence that suggests that bacterial biofilm aggregates play a role in the delayed healing of chronic wounds [

8,

9,

10]. By its simplest definition, a biofilm is a group of bacterial cells imbedded in a matrix, that has increased tolerance to antimicrobials and the host defense system. It is estimated that biofilms are present in approximately ~80% [

10,

11] of chronic wounds as compared to only 6% of acute wounds [

9]. These numbers may be underestimated as biofilms are not uniformly distributed [

12] and the chance of identification will be affected by the method used as well as the sampling approach [

13,

14]. The bacteria found in wounds are thought to originate from the patients’ skin or other body parts such as the oral cavity or the gut, or from the outside environment [

15]. In most wounds, the endogenous bacteria, i.e., the ones derived from the patients themselves, are thought to predominate [

16]. Normal wound healing progresses through the phases of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling in a matter of weeks to months depending on wound size [

17]. However, the presence of biofilms is hypothesized to cause an exaggerated innate immune response, leaving the wound in a chronic inflammatory state with collateral tissue damage [

2,

18]. Proper management of biofilms in chronic wound infections is therefore believed to be key in successful healing [

19].

The complete eradication of the residing biofilm is difficult to achieve due to the numerous and complex survival strategies utilized [

20]. The survival strategies are believed to result from a combination of the inherent biofilm properties together with interactions between the microbes and the host environment [

21]. Several reviews focus on the topic of biofilm resistance and tolerance [

22,

23,

24]. In particular, studies that compare antimicrobial resistance in planktonic and biofilm-grown cultures in vitro are plentiful (see [

25] for a meta-analysis).

2. Current Biofilm Research

Currently, most of the research within biofilm resistance is based on in vitro experiments or animal models which are significantly different from studying chronic wounds in patients [

21,

26]. Essentially, during in vitro experiments an organism (or a component thereof) is isolated from its natural environment to study its mechanisms or behaviors in detail under controlled settings. In vitro observations certainly have been invaluable in discovering cellular processes, mechanistic actions, or basic interactions between entities. It is, however, unfair to assume that findings from a test tube can be directly extrapolated to in vivo conditions and caution should be taken when attempting to translate such results. Under certain conditions in vitro culturing has been shown to better resemble in vivo bacterial transcriptomes than infected animal models [

27]. Over the years, novel and sophisticated chronic wound models have been developed which aim at simulating certain features of in vivo conditions and a thorough breakdown of these models was recently reviewed [

28].

While animal models do include all the components observed in the human environment, such as a complex tissue structure and a functioning immune system, several papers have concluded that data obtained from rodent models in particular, do not correlate well with what is found in humans [

27,

29]. Common for all animal models is that none of them recapitulate all features of human skin, healing processes, and the immune response.

Firstly, the anatomy of human skin is best resembled by porcine models. In pigs, the dermal to epidermal thickness ratio is similar to human skin [

30], there is a lack of panniculus carnosus, sparse body hair (but still presence of hair follicles) and the dermis has a similar architecture although eccrine glands are not present in pigs [

29]. In comparison, rodent models have thin epidermal and dermal layers, a dense hair coat and have panniculus carnosus resulting in loose skin. A very relevant consideration for chronic wound research is the mode of healing. In humans and pigs, wound closure is achieved mainly by re-epithelization, resulting in scar tissue, whereas animals that have panniculus carnosus use contraction of skin for closing wounds.

Secondly, the immune response toward infecting bacteria appears to be different between animal models. This has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere but among other factors, the leucocyte to neutrophil ratio is widely different between mice and humans as well as the induction of both the innate and adaptive immune system [

31]. In contrast, the immune system of pigs has several similarities to that of humans, with only a few disparities [

32,

33].

Owing to the obvious constraints of having animal models that possess the same co-morbidity development over time as seen in humans (diabetes, atherosclerosis, lifestyle diseases, etc.), no animal models are able to capture the complexity of a human wound spanning months to years without proper healing [

34]. However, many models have been developed to simulate certain features of the co-morbidities such as ischemic wounds, ischemic reperfusion wounds, pressure ulcers, and diabetic wounds [

35].

Lastly, there is the question of the chronicity of the induced wound in the animal or the in vitro model. The term ‘chronic’ does not have a universal definition, but usually a wound that has not healed within 12 weeks is categorized as being chronic. For ethical and practical reasons, inductions of long-lasting wounds or laboratory models, respectively, are not trivial. However, if a shorter period is used important features may remain undiscovered and the experiment may not reflect the situation in an in vivo chronic wound.

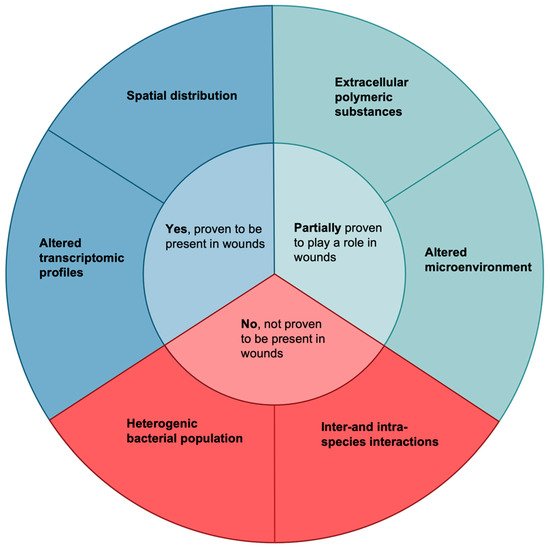

Even though in vitro and animal models do not recapitulate every aspect of human chronic wounds they are still invaluable in increasing our knowledge about the mechanistic and molecular causes of non-healing wounds. In this review, we will make clear separations between data obtained from human wound samples and those observed only in vitro or in animal models to elucidate the biofilm survival strategies proven to exist and be of significance in clinical wounds. Additionally, while certain biofilm attributes may have been observed in human wound samples, their role in increased bacterial survival may not yet have been elucidated. Factors potentially involved in the increased survival of bacteria in chronic wounds are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Factors that may cause increased survival of bacteria in wounds. These six qualities are all biofilm attributes or biofilm-related attributes which have been speculated to increase their survival in human wounds. Only two have been demonstrated to exist and lead to increased biofilm survival in wounds by use of clinical wound samples, namely altered transcriptomic profiles [

36,

37,

38,

39] and spatial distribution [

40,

41]. Two factors have been partially proven to play a role: extracellular polymeric substances [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48] and an altered microenvironment [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Both of these factors have been shown to exist in wounds, but their role in leading to increased survival has not been proven in clinical samples. Finally, the last two factors, a heterogenic bacterial population and inter-and- intra-species interactions, have only been shown to exist in vitro or in other conditions.

3. Altered Transcriptomic Profiles

Transcriptomic analyses are increasingly used to survey the specific gene regulations of infectious microbes. By using RNA-sequencing approaches to study gene expression in human samples, changes of e.g. bacterial virulence, metabolism, antibiotic resistance, interactions, etc. can be studied in vivo and compared to reference strains grown in vitro. E.g., a comparison of the transcriptome of S. aureus isolated from prosthetic joint infections and laboratory-grown cultures revealed that S. aureus from clinical samples expressed a change in several metabolic pathways and an increase in 131 genes encoding virulence factors, such as a-hemolysin and g-hemolysin [36]. Similarly, a unique transcriptomic profile was identified for P. aeruginosa in chronic infections, where antibiotic resistance-associated genes, including efflux pumps, were upregulated in chronic wounds compared to in vitro grown cultures [37]. Metatranscriptomic analysis of diabetic foot infections identified upregulated expression of pathways involved in synthesis and regulation of siderophores (iron-chelating molecules) and cell-surface components (fimbria and flagellum) [38]. Recently, the first paper was published that considered both the bacterial and human transcriptome in patients with diabetic foot ulcers [39]. The upregulation of genes encoding resistance and virulence together with altered metabolic pathways are thought to increase the survival potentials of microbial biofilms in wounds [37].

The challenge of collecting sufficient useful material from clinical samples for sequencing can potentially be overcome by using single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) [

40,

41]. The use of this technique is increasing for transcriptome studies of eukaryotic cells. However, scRNA-seq of bacteria is in its infancy, and to date, only a few studies have been published [

42,

43].

4. Spatial Distribution

To better understand biofilms it is not only important to know which bacterial species are present but also the organization and distribution of bacteria within the wound. A study investigating samples from three patients with chronic wounds showed that when dividing and comparing samples from different areas of the same wound, the abundance of bacteria varied significantly [13]. Another study by Davies et al. investigated which bacteria could be identified in wounds using either culturing of a surface swab or molecular methods of a punch biopsy [44]. The results showed that more than 40% of the bacteria identified on the punch biopsy using molecular methods were not isolated through culturing of the swab [44]. While the discrepancies between different diagnostic methods have been discussed before [13,45,46] and will be highlighted later, the results indicate an uneven distribution of bacteria within chronic wounds.

To our knowledge, only a single study has investigated the depth distribution of bacterial biofilms in chronic wounds [

47]. By using peptide nucleic acid-based fluorescence

in situ hybridization (PNA-FISH) combined with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), the depth distribution of

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa was quantified in samples from nine chronic venous leg ulcers. The authors found a non-random distribution where

S. aureus was primarily located 20-30 µm from the wound surface, whereas

P. aeruginosa was primarily located 50-60 µm from the wound surface both as single species biofilms. These findings were suggested as a possible explanation for previous findings of discrepancies between surface swabs and tissue samples [

47]. It was speculated that the location of the biofilm aggregates could affect survival, as topically added compounds might not reach the biofilms located deep within the wound bed. This has previously been observed in a clinical study where patients were treated with silver-containing dressings [

48]. Surface swaps showed a decrease in bacterial numbers, but enumeration of bacteria from biopsies did not show a reduction in microbe numbers, indicating that deeper located pathogens had enhanced survival. Moreover, any added compound could also be diluted to sub-inhibitory concentrations as it moves through the wound debris before it reaches its target, providing another survival benefit for microbes located deeper into the wound.

5. Perspectives

The ubiquity of biofilms in chronic wounds is at this point a near universally accepted fact [

10]. However, it has still not been proven that the presence of biofilms causes an acute infection to turn into a chronic state. While the microenvironment of chronic wounds surely seems to promote a non-healing state, the central paradigm remains as to whether the presence of biofilms exacerbates wound healing, or if the chronic wound environment generates a favorable condition for a biofilm to settle. In any case, hard-to-eradicate biofilms are present in chronic wounds but whether it is the presence of a biofilm itself, the slow growth rate of the biofilm-residing microbes, or a combination of both that leads to chronicity is not known. Recently, it was shown that the determining factor for an acute versus a chronic lung infection was not the presence of a biofilm but rather the growth rate of the microbes within the biofilms [

105]. Future studies which further highlight the differences between biofilms in acute versus chronic infections might help us in our understanding of what causes chronicity and thereby provide us with potential targets for novel treatments.

We recognize that the use of animal models for studying biofilms in chronic wounds is a necessity and particularly beneficial in answering questions of causation and correlation in terms of wound healing when biofilms are present. Such studies have already been carried out and specifically show that when biofilms are added to trauma-induced wounds (e.g., punch wounds), the infected wounds heal slower than their non-infected counterparts [

107,

108]. However, while such studies are highly valuable, they infer little about the specific situation of a chronic wound that has been developing for weeks or months. This distinction between acute and chronic wounds has a major impact on several factors, and while it would cause great ethical concerns to induce long-lasting wounds in animal models, the limitations of studying wounds that have only been developing for a few days must be recognized.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms10040775