Metabolic diseases, such as obesity, Type II diabetes and hepatic steatosis, are a significant public health concern affecting more than half a billion people worldwide. The prevalence of these diseases is constantly increasing in developed countries, affecting all age groups. The pathogenesis of metabolic diseases is complex and multifactorial. Inducer factors can either be genetic or linked to a sedentary lifestyle and/or consumption of high-fat and sugar diets. In 2002, a new concept of “environmental obesogens” emerged, suggesting that environmental chemicals could play an active role in the etiology of obesity. Bisphenol A (BPA), a xenoestrogen widely used in the plastic food packaging industry has been shown to affect many physiological functions and has been linked to reproductive, endocrine and metabolic disorders and cancer. BPA was banned in baby bottles in Canada in 2008 and in all food-oriented packaging in France from 1 January 2015. Since the BPA ban, substitutes with a similar structure and properties have been used by industrials even though their toxic potential is unknown. Bisphenol S has mainly replaced BPA in consumer products as reflected by the almost ubiquitous human exposure to this contaminant.

- BPA substitutes

- metabolic disorders

- endocrine disruptors

- bisphenol A

1. Introduction

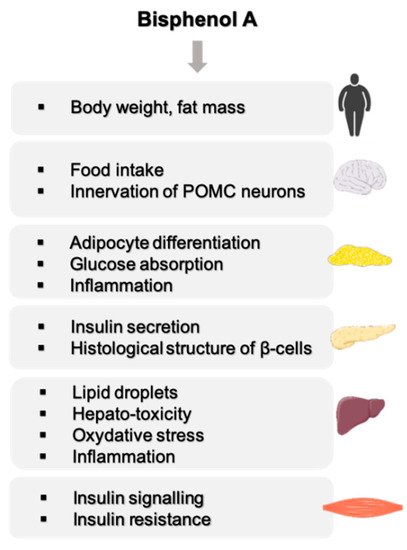

2. A Strong Link between BPA and Metabolic Disorders

2.1. Effect of BPA on Body Weight

2.2. Effect of BPA on the Central Nervous Functions Related to Energy Homeostasis

2.3. BPA, a Disruptor of Carbohydrate Homeostasis

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23084238

References

- Heindel, J.J. History of the Obesogen Field: Looking Back to Look Forward. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 14.

- Shahnazaryan, U.; Wójcik, M.; Bednarczuk, T.; Kuryłowicz, A. Role of Obesogens in the Pathogenesis of Obesity. Medicina 2019, 55, 515.

- Fénichel, P.; Brucker-Davis, F.; Chevalier, N. The history of Distilbène® (Diethylstilbestrol) told to grandchildren—The transgenerational effect. In Annales d’Endocrinologie; Elsevier Masson: Paris, France, 2015; Volume 76, pp. 253–259.

- Rudel, R.A.; Gray, J.M.; Engel, C.L.; Rawsthorne, T.W.; Dodson, R.E.; Ackerman, J.M.; Rizzo, J.; Nudelman, J.L.; Brody, J.G. Food Packaging and Bisphenol A and Bis(2-Ethyhexyl) Phthalate Exposure: Findings from a Dietary Intervention. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 914–920.

- Vom Saal, F.S.; Cooke, P.S.; Buchanan, D.L.; Palanza, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Nagel, S.C.; Parmigiani, S.; Welshons, W.V. A physiologically based approach to the study of bisphenol A and other estro-genic chemicals on the size of reproductive organs, daily sperm production, and behavior. Toxicol. Ind. Health 1998, 14, 239–260.

- Rochester, J.R. Bisphenol A and human health: A review of the literature. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 42, 132–155.

- Heindel, J.J.; Blumberg, B. Environmental Obesogens: Mechanisms and Controversies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 59, 89–106.

- Hwang, S.; Lim, J.-E.; Choi, Y.; Jee, S.H. Bisphenol A exposure and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk: A meta-analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 81.

- Liu, B.; Lehmler, H.-J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zong, G.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Wallace, R.B.; Bao, W. Bisphenol A substitutes and obesity in US adults: Analysis of a population-based, cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e114–e122.

- Lang, I.A.; Galloway, T.S.; Scarlett, A.; Henley, W.E.; Depledge, M.; Wallace, R.B.; Melzer, D. Association of Urinary Bisphenol A Concentration with Medical Disorders and Laboratory Abnormalities in Adults. JAMA 2008, 300, 1303.

- Carwile, J.L.; Michels, K.B. Urinary bisphenol A and obesity: NHANES 2003–2006. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 825–830.

- Melzer, D.; Rice, N.E.; Lewis, C.; Henley, W.E.; Galloway, T.S. Association of Urinary Bisphenol A Concentration with Heart Disease: Evidence from NHANES 2003/06. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8673.

- Shankar, A.; Teppala, S. Relationship between Urinary Bisphenol A Levels and Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 3822–3826.

- Vandenberg, L.N. Low-Dose Effects of Hormones and Endocrine Disruptors. Vitam. Horm. 2014, 94, 129–165.

- Miyawaki, J.; Sakayama, K.; Kato, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Masuno, H. Perinatal and Postnatal Exposure to Bisphenol A Increases Adipose Tissue Mass and Serum Cholesterol Level in Mice. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2007, 14, 245–252.

- Rubin, B.S.; Murray, M.K.; Damassa, D.A.; King, J.C.; Soto, A.M. Perinatal exposure to low doses of bisphenol A affects body weight, patterns of estrous cyclicity, and plasma LH levels. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 675–680.

- Ryan, K.; Haller, A.M.; Sorrell, J.E.; Woods, S.C.; Jandacek, R.J.; Seeley, R.J. Perinatal Exposure to Bisphenol-A and the Development of Metabolic Syndrome in CD-1 Mice. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2603–2612.

- Susiarjo, M.; Xin, F.; Bansal, A.; Stefaniak, M.; Li, C.; Simmons, R.A.; Bartolomei, M. Bisphenol A Exposure Disrupts Metabolic Health across Multiple Generations in the Mouse. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 2049–2058.

- Angle, B.M.; Do, R.P.; Ponzi, D.; Stahlhut, R.W.; Drury, B.E.; Nagel, S.C.; Welshons, W.V.; Besch-Williford, C.L.; Palanza, P.; Parmigiani, S.; et al. Metabolic disruption in male mice due to fetal exposure to low but not high doses of bisphenol A (BPA): Evidence for effects on body weight, food intake, adipocytes, leptin, adiponectin, insulin and glucose regulation. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 42, 256–268.

- Somm, E.; Schwitzgebel, V.M.; Toulotte, A.; Cederroth, C.R.; Combescure, C.; Nef, S.; Aubert, M.L.; Hüppi, P.S. Perinatal Exposure to Bisphenol A Alters Early Adipogenesis in the Rat. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1549–1555.

- Wei, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Ying, C.; Chen, J.; Song, L.; Zhou, Z.; Lv, Z.; Xia, W.; Chen, X. Perinatal Exposure to Bisphenol A at Reference Dose Predisposes Offspring to Metabol-ic Syndrome in Adult Rats on a High-Fat Diet. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3049–3061.

- Magdalena, P.A.; Vieira, E.; Soriano, S.; Menes, L.; Burks, D.; Quesada, I.; Nadal, A. Bisphenol A Exposure during Pregnancy Disrupts Glucose Homeostasis in Mothers and Adult Male Offspring. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1243–1250.

- Ishido, M.; Masuo, Y.; Kunimoto, M.; Oka, S.; Morita, M. Bisphenol A causes hyperactivity in the rat concomitantly with impairment of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 76, 423–433.

- Kabuto, H.; Amakawa, M.; Shishibori, T. Exposure to bisphenol A during embryonic/fetal life and infancy increases oxidative injury and causes underdevelopment of the brain and testis in mice. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2931–2940.

- Ryan, B.C.; Vandenbergh, J.G. Developmental exposure to environmental estrogens alters anxiety and spatial memory in female mice. Horm. Behav. 2006, 50, 85–93.

- Richter, C.A.; Birnbaum, L.; Farabollini, F.; Newbold, R.R.; Rubin, B.S.; Talsness, C.E.; Vandenbergh, J.G.; Walser-Kuntz, D.R.; Saal, F.S.V. In vivo effects of bisphenol A in laboratory rodent studies. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 24, 199–224.

- Vom Saal, F.S.; Richter, C.A.; Ruhlen, R.R.; Nagel, S.C.; Timms, B.G.; Welshons, W.V. The importance of appropriate controls, animal feed, and animal models in inter-preting results from low-dose studies of bisphenol A. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2005, 73, 140–145.

- Mackay, H.; Patterson, Z.R.; Khazall, R.; Patel, S.; Tsirlin, D.; Abizaid, A. Organizational Effects of Perinatal Exposure to Bisphenol-A and Diethylstilbestrol on Arcuate Nucleus Circuitry Controlling Food Intake and Energy Expenditure in Male and Female CD-1 Mice. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 1465–1475.

- Mackay, H.; Patterson, Z.R.; Abizaid, A. Perinatal Exposure to Low-Dose Bisphenol-A Disrupts the Structural and Functional Development of the Hypothalamic Feeding Circuitry. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 768–777.

- Salehi, A.; Loganathan, N.; Belsham, D.D. Bisphenol A induces Pomc gene expression through neuroinflammatory and PPARγ nuclear receptor-mediated mechanisms in POMC-expressing hypo-thalamic neuronal models. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 479, 12–19.

- Martinez-Pinna, J.; Marroqui, L.; Hmadcha, A.; Lopez-Beas, J.; Soriano, S.; Villar-Pazos, S.; Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Dos Santos, R.S.; Quesada, I.; Martin, F.; et al. Oestrogen receptor β mediates the actions of bisphenol-A onion channel expression in mouse pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1667–1680.

- Villar-Pazos, S.; Martinez-Pinna, J.; Castellano-Muñoz, M.; Magdalena, P.A.; Marroqui, L.; Quesada, I.; Gustafsson, J.-A.; Nadal, A. Molecular mechanisms involved in the non-monotonic effect of bisphenol-a on Ca2+ entry in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11770.

- Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Morimoto, S.; Ripoll, C.; Fuentes, E.; Nadal, A. The estrogenic effect of bisphenol A disrupts pancreatic beta-cell function in vivo and induces insulin resistance. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 106–112.

- Nadal, A.; Magdalena, P.A.; Soriano, S.; Quesada, I.; Ropero, A.B. The pancreatic β-cell as a target of estrogens and xenoestrogens: Implications for blood glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 304, 63–68.

- Ropero, A.B.; Pang, Y.; Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Thomas, P.; Nadal, Á. Role of ERβ and GPR30 in the endocrine pancreas: A matter of estrogen dose. Steroids 2012, 77, 951–958.

- Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Ropero, A.B.; Carrera, M.P.; Cederroth, C.R.; Baquie, M.; Gauthier, B.R.; Nef, S.; Stefani, E.; Nadal, A. Pancreatic insulin content regulation by the estrogen receptor ER alpha. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2069.

- Soriano, S.; Alonso-Magdalena, P.; García-Arévalo, M.; Novials, A.; Muhammed, S.J.; Salehi, A.; Gustafsson, J.-A.; Quesada, I.; Nadal, A. Rapid Insulinotropic Action of Low Doses of Bisphenol-A on Mouse and Human Islets of Langerhans: Role of Estrogen Receptor β. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31109.

- Makaji, E.; Raha, S.; Wade, M.G.; Holloway, A.C. Effect of Environmental Contaminants on Beta Cell Function. Int. J. Toxicol. 2011, 30, 410–418.

- Dahlman-Wright, K.; Cavailles, V.; Fuqua, S.A.; Jordan, V.C.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Korach, K.; Maggi, A.; Muramatsu, M.; Parker, M.G.; Gustafsson, J. International Union of Pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 773–781.

- Thomas, P.; Dong, J. Binding and activation of the seven-transmembrane estrogen receptor GPR30 by environmental estrogens: A potential novel mechanism of endocrine disruption. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 102, 175–179.

- Sharma, G.; Prossnitz, E.R. Mechanisms of estradiol-induced insulin secretion by the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPR30/GPER in pancreatic β-cells. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3030–3039.

- Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Laribi, O.; Ropero, A.B.; Fuentes, E.; Ripoll, C.; Soria, B.; Nadal, A. Low doses of bisphenol A and diethylstilbestrol impair Ca2+ signals in pancreatic α-cells through a nonclassical membrane estrogen receptor within intact islets of Langer-hans. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 969–977.