Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Substance Abuse

Cocaine is one of the most consumed stimulants throughout the world, as official sources report. It is a naturally occurring sympathomimetic tropane alkaloid derived from the leaves of Erythroxylon coca, which has been used by South American locals for millennia. Cocaine can usually be found in two forms, cocaine hydrochloride, a white powder, or ‘crack’ cocaine, the free base.

- sympathomimetics

- crack

- pharmacokinetics

- pharmacodynamics

- toxicity

- cocaine hydrochloride

- drug abuse

1. Introduction

Cocaine is a naturally occurring sympathomimetic alkaloid from the plant Erythroxylon coca that has been used as a stimulant, by chewing the leaves or brewing teas, in South America for over 5000 years. Cocaine was firstly isolated from the leaves in the mid-1800s and was at that time considered safe and used in toothache drops, nausea pills, energy tonics, and the original ‘Coca-Cola’ beverage [1,2]. Currently, it is found in one of two forms for (ab)use: Cocaine hydrochloride (also known as ‘coke’, ‘blow’ or ‘snow’), a fine white crystalline powder, which is soluble in water and consumed mainly through the intranasal route (‘sniffing’/‘snorting’), orally or intravenously; or as a free base (resulting from reaction of cocaine hydrochloride with ammonium or baking soda), commonly known as ‘crack cocaine’ or simply ’crack’, and typically consumed via inhalation (the solid mass is cracked into ‘rocks’ that are smoked, using glass or makeshift pipes) [2,3].

Cocaine abuse remains a significant public health problem with serious socio-economic consequences worldwide [4]. According to the most recent World Drug Report, 0.4% of the global population aged 15–64 reported cocaine use in 2019—this corresponds to approximately 20 million people [5]. The latest edition of the European Monitoring Centre for Drug and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) Drug Report states that it remains the second most abused substance in the European Union, second only to cannabis [6]. Furthermore, despite the global COVID-19 pandemic, European authorities have intercepted at seaports growing amounts of cocaine in 2020 [5]. All the while, case reports detailing the harmful consequences of cocaine use abound [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

2. Natural Occurrence and Chemical Characterisation of Erythroxylum coca

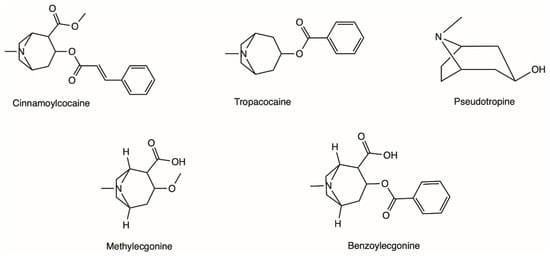

The coca shrub, from which cocaine is extracted, is a plant of the genus Erythroxylum that grows in Central and South America, and it has over 250 identified species, of which the two most important are E. coca and Erythroxylum novogranatense; however it is from E. coca Lam. var. coca (also referred to as ‘Bolivian’ or ‘Huanuco’ coca) that the majority of cocaine supply is extracted [21,22]. The coca plant presents large, thick, dark green leaves with an elliptical shape and a somewhat sharp apex, and has small red fruits [23]. Circa 18 different alkaloids can be found in the leaves of the coca plant, such as cinnamoylcocaine, tropacocaine, methylecgonine, benzoylecgonine (BE) and pseudotropine—all of these are significantly less euphoric and less toxic than cocaine (Figure 1) [21,22].

Figure 1. Examples of different alkaloids that can be found in the leaves of the coca plant.

Coca leaves have been traditionally used by the indigenous Andean populations and were/are consumed mostly by chewing; coca leaves as a part of religious occasions and other celebrations by the Inca, as well as employed for medicinal purposes [22]. It was from the coca leaves that Albert Niemann first isolated cocaine in 1859–1860 [21,24]. A study from one hundred years later found that dry leaves of E. coca var. coca have around 6.3 mg of cocaine per gram of plant material [25].

3. Physicochemical Properties of Cocaine and Analytical Methods for Identification

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid with weak basic properties. In the free base form, cocaine is unionised and insoluble in aqueous medium, displaying a boiling point of 187 °C; while its ionised hydrochloride salt is readily dissolved in water and presents high stability at very high temperatures, as such, it does not volatilise in the smoke. Table 1 summarises a few of the physical and chemical properties of cocaine [26,27].

Table 1. Physical and chemical properties of cocaine.

| Cocaine Form | Cocaine Hydrochloride | Cocaine Free Base |

|---|---|---|

| Other names it is known by | ‘coke’, ‘snow’, ‘blow’ | ‘crack’ |

| CAS | 53-21-4 | 50-36-2 |

| Molecular formula | C17H22ClNO4 | C17H21NO4 |

| Molecular weight | 339.8 g mol−1 | 303.35 g mol−1 |

| Boiling point | - | 187 °C |

| Melting point | 195 °C | 98 °C |

| Solubility in water | 2 g/mL | 1.7 × 10−3 g/mL |

| pKa; pKb (at 15 °C) | - | 8.61; 5.59 |

| Log P | - | 2.3 |

4. Pharmacodynamics

Cocaine has different pharmacodynamic properties that make possible its use as a local anaesthetic and as a sympathomimetic stimulant at the central nervous system (CNS).

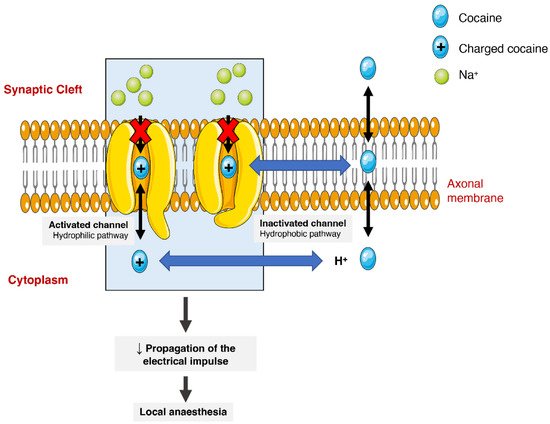

The anaesthetic action of cocaine is related to its capacity to block voltage-gated sodium channels by stabilizing these channels in an inactive state (Figure 3). The binding of cocaine to the channel’s pore prevents sodium from flowing through it into the cells and thus blocking the depolarization process and the propagation of the electrical impulses [1,24,75]. The current medical use is very limited as most countries consider it obsolete. It can still be used as a topical anaesthetic, which might be particularly useful for endoscopic sinus surgery, given its vasoconstrictive effects. There are, however, controversies related to the development of mild morbidities, such as hypertension and tachycardia [76].

Figure 3. Schematic representation of cocaine’s interaction with voltage-gated sodium channels. Cocaine enters the channels and binds to them by two pathways (hydrophilic and hydrophobic). In the hydrophobic pathway cocaine interacts with the sodium channel at the membrane level, alternatively in hydrophilic pathway, the cocaine is ionized in cytoplasm before the interaction. In both cases, the flow of sodium is blocked, which diminishes the propagation of electrical impulses and causes a local anaesthetic effect.

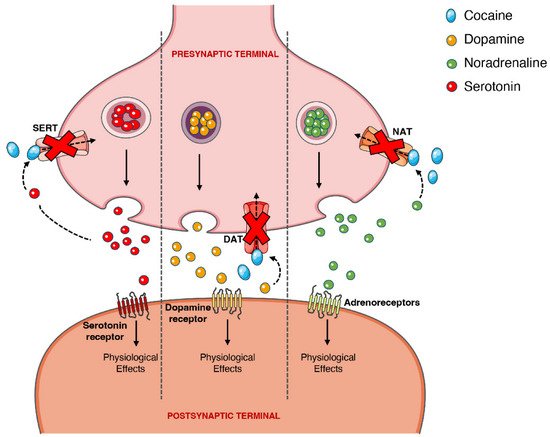

On the other hand, the psychoactive and sympathomimetic effects of cocaine derive from the blockade of presynaptic transporters responsible for the reuptake of serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine. In the case of the latter, the blockade of the presynaptic dopamine transporter (DAT) in the synaptic cleft causes an extracellular increase in dopamine with an overstimulation of the dopaminergic postsynaptic receptors, inducing the euphoric ‘rush’ [3,53]. Further mechanisms of tolerance at this level are responsible by the subsequent drop in the dopamine levels experienced as a dysphoric ‘crash’. A recent meta-analysis showed that chronic cocaine users display a significant reduction in dopamine receptors D2 and D3 in the striatum, the caudate and putamen brain regions, as well as a significantly increased availability of DAT all over the striatum [77].

When cocaine is consumed, an exacerbated dopaminergic activity along the mesocorticolimbic pathways occurs. Neurons from these pathways are located in the ventral tegmental area and project to other brain locations, including the nucleus accumbens [78]. This could explain why the drug has such an addictive potential, since it is well acknowledged that the nucleus accumbens may have an important role in the rewarding and addictive properties of cocaine and other drugs [79]. However, it should be mentioned that cocaine’s capacity to increase serotoninergic activity (which may induce seizures) could also contribute to the drug’s addictive potential [80,81]. Figure 4 schematically represents cocaine’s pharmacodynamic action over the monoaminergic system.

Figure 4. Schematic representation of cocaine’s pharmacodynamics at the noradrenergic, serotonergic or dopaminergic synapse. Cocaine acts by blocking the presynaptic transporters of dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline, preventing the reuptake of the neurotransmitters into the presynaptic terminal, which will cause intense and prolonged stimulation of the postsynaptic receptors. DAT, dopamine transporter; NAT, noradrenaline transporter; SERT, serotonin transporter.

The sympathomimetic properties of cocaine are related to the above-mentioned inhibition of noradrenaline reuptake via noradrenaline transporter (NAT). Because cocaine impedes this reuptake of noradrenaline, and thus increases its availability, there will be an increase in the stimulation of the α- and β-adrenergic receptors, and an augmented adrenergic response—which relates to the marked vasoconstrictive properties of the drug (responsible for a few of the cardiotoxic effects) [2,82,83].

Additionally, cocaine also has the capacity to directly target adrenergic, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and sigma and kappa opioid receptors. Cocaine affects NMDA receptors, as exposure to the drug modulates (for greater or lesser) receptor subunit expression, alters receptor distribution in the synapse, and influences the crosstalk of the NMDA receptor with the dopaminergic receptor D1, in different brain areas, for example, the nucleus accumbens, the ventral tegmental area and the prefrontal cortex [84]. Lastly, cocaine acts directly over the sigma opioid receptors, binding with greater affinity to the σ1 receptor than to the σ2 receptor; agonism at the σ1 by cocaine partially mediates the hyperlocomotion and seizures, and these receptors are paramount in the establishment of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in mice [53,82,85].

Recently, it has been suggested that the pharmacological action of cocaine over DAT may not be as simple as the sole inhibition of the transporter’s reuptake function, as its behaviour is distinct from other DAT inhibitors of equal or greater potency (with matched capacity for crossing the BBB) and resembles methylphenidate (a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor that also induces the release of synaptic dopamine). As such, it was hypothesised that, similar to amphetamines, cocaine functions as a negative allosteric modulator of DAT (i.e., a DAT ‘inverse agonist’), altering transporter function and reversing transport direction [86]. However, more research is necessary in this area to further clarify cocaine pharmacodynamics.

5. Effects and Toxicity of Cocaine

Cocaine’s LD50 has been previously determined in a few studies using different animal models: in mice, using an intraperitoneal administration, it was valued at 95.1 mg/Kg [1]; in rats and dogs using an intravenous route, the values were 17.5 and 21 mg/Kg, respectively [53].

As previously stated, cocaine targets the CNS, inducing a myriad of physical, psychological, and behavioural effects, which are inherently dependent on the user’s profile, route of administration and dose. While many of the severe pathological effects induced by cocaine could be attributed to a chronic consumption pattern (e.g., neurodegeneration, premature brain aging, depression, blood vessels damage), certain effects, such as tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, tremors, seizures, mydriasis, headaches, abdominal pain, muscle hyperactivity, haemorrhagic stroke, and multiorgan failure, arise with acute abuse patterns (all too often, even after a single dose). It is important to keep in mind that some cocaine metabolites maintain the ability to cross the BBB, thus contributing to both desirable effects and adverse/toxic reactions reported by users [54].

6. Abuse Potential, Dependence, and Tolerance

The abuse and dependence of cocaine is strongly related to the drug’s capacity to induce the release of dopamine within the mesocorticolimbic circuit (also known as the reward system). As the user continues to consume cocaine, desensitization occurs and so larger doses are necessary to induce stimuli of the same magnitude as before, as well as to minimize withdrawal symptoms [129]. Cocaine dependence/addiction specifically is not included in the Diagnostics and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5); however, the criteria for stimulant use disorder can be applied. The criteria set for this are: hazardous use, neglected major life roles (e.g., work, parenting) to use, social/interpersonal problems related to use, craving, withdrawal, tolerance, activities given up to use, much time spent using, used larger amounts/longer, physical/psychological problems related to use, and repeated attempts to quit/control use [130].

Cocaine has been demonstrated to possess an elevated abuse potential, with experimental studies reporting it induces place preference conditioning and readily acts as reinforcer for drug self-administration [131,132,133,134]. Di Chiara and Imperato tested the effect of cocaine on extracellular dopamine content in two terminal dopaminergic brain areas of rats (the dorsal caudate nucleus and the nucleus accumbens septi), and found that the drug has the capacity to increase dopamine concentrations in both the areas, but especially in the nucleus accumbens, postulating that this ability could be a key element of drugs of abuse [135]. The dorsal striatum also seems to be involved in cocaine dependence, given that in dependent individuals, the exposure to cocaine cues (a video of subjects consuming ‘crack’) reduced the binding of a radioligand to D2 receptor in this brain region, and greater displacement of the radioligand corresponded with craving. Subjects with the highest degrees of withdrawal and addiction also had the greatest degree of displacement [136]. Furthermore, Volkow et al. determined that, when compared to non-dependent individuals, cocaine-dependent subjects demonstrate impaired dopamine increases in the dorsal and ventral striatum in response to methylphenidate, which did not differ from that elicited by the placebo. This same study found that the baseline levels of dopaminergic D2 and D3 receptors of the ventral striatum were markedly lower for cocaine abusers, [137]. Recent advances in the field revealed that the heteromerization of receptors D2-NMDA induced by a cocaine regimen in mice was sustained after an abstinence period, and was associated with behavioral sensitization by the drug [138]. Furthermore, D2-NDMA heteromeric complexes were demonstrated to be necessary for the development and reinstatement of conditioned place preference induced by cocaine, and inhibiting their formation did not interfere with natural reward processes [138].

‘Crack’ dependence has been proven to affect working memory: ‘crack’-dependent young women performed similarly to healthy older women, in an inferior manner to younger healthy women (for both groups) [139]. It seems clear that, while a fuller and more complete picture of the mechanisms that underlie cocaine abuse and dependence is beginning to form, more research is still necessary to better help those struggling with cocaine addiction.

The continued use of cocaine at high doses can lead to the development of tolerance to the cardiovascular and subjective effects reported by users, with cocaine-dependent volunteers who underwent continuous infusions describing a subdued ‘rush’ as time passed, but still feeling the ‘high’ [140]. In fact, one study approaching long-term cocaine users in Philadelphia and applying the ‘Cocaine History Questionnaire’ found that there was a negative correlation between the amount of cocaine consumed and the sensation of euphoria achieved from the use, while some negative effects (mood swings, paranoia and agitation) associated with the use increased [141]. Animal studies have also helped to shed some light regarding cocaine tolerance. At the pharmacodynamic level, cocaine self-administration at 1.5 mg/Kg (40 injections per day for five consecutive days) reduced the amount of dopamine and the velocity at which the neurotransmitter is released, as observed in rat brain slices [142]; this same treatment led to a reduction in effect of several dopamine-noradrenaline uptake blockers (bupropion and nomifensine), but did not affect response to dopaminergic releasers (e.g., methamphetamine and phentermine). Furthermore, the same regimen of cocaine intake led Sprague Dawley rats to increase the number of self-administrations within the first hour of the session over five consecutive sessions, and a tolerance for the locomotor-activating effects of cocaine [143]. In addition, the self-administration of cocaine caused a reduction in the amount of presynaptic dopamine and its uptake in the nucleus accumbens, and DAT showed a reduced sensitivity to cocaine’s capacity to inhibit dopamine uptake [143]. The development of tolerance—where the pleasurable effects of the drug are diminished—could lead the individual to feel the need to administer a new bolus (increase the dose and/or intake frequency) while plasma concentrations are still elevated, and thus increasing the likelihood of severe and even possibly fatal toxicity [2,96,144].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/toxins14040278

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!