Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Because of demographic aging, the prevalence of arterial hypertension (HTN) and cardiac arrhythmias, namely atrial fibrillation (AF), is progressively increasing. Not only are these clinical entities strongly connected, but, acting with a synergistic effect, their association may cause a worse clinical outcome in patients already at risk of ischemic and/or haemorrhagic stroke and, consequently, disability and death.

- hypertension

- atrial fibrillation

- primary hyperaldosteronism

1. Introduction

The overall prevalence of hypertension (HTN) in adults is roughly 30–45% [1] and becomes even more common with advancing age [2]. HTN is also a well-known risk factor for atrial fibrillation (AF) [3,4,5], which may even occur when borderline values of blood pressure (BP) are recorded [6,7,8,9,10]. Moreover, AF exerts an important prognostic role in hypertensive patients, thus potentially leading to ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, hospitalisations for heart failure, and, in the worst circumstances, death [10,11,12]. Therefore, it stands to reason that primary prevention measures devoted to reducing incident AF are required to avoid potentially troublesome cardiac and cerebrovascular events which may occur in this clinical scenario. Moreover, increasing age and the associated burden of other comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea would synergistically act with HTN as major contributors to AF development and progression [10].

2. Common Pathophysiological Aspects Explaining the Link between Hypertension and Cardiac Arrhythmias

As observed in animal models, HTN per se is associated with ion channel imbalance and the progressive development of myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive hearts [13,14,15]. The ensuing molecular and structural alterations would therefore represent a fertile substrate for arrhythmogenesis. On the one hand, HTN-related shear stress would lead to both a long outward potassium (K+) current (Kv1.5) [13] and the altered release of intracellular calcium (Ca2+) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum [14], thus leading to a shorter action potential duration and delayed afterdepolarizations (DAD) in myocardial cells, respectively. In fact, a shorter action potential duration would predispose to enhanced automatism and re-entrant mechanisms [16]. In addition to ion channel abnormalities, HTN is also associated with maladaptive gap junction remodelling due to the abnormal expression of gap junction proteins such as connexin 43 and 40 [15,17] which would determine the abnormal conduction properties and fibrotic evolution of myocardial tissue, thus prompting nonuniform anisotropy, slow conduction, and, therefore, arrhythmogenesis in hypertensive hearts. In addition to this, cardiovascular risk factors, HTN included, are accompanied by low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress, which further promote ion channels and connexin downregulation/dysfunction, abnormal Ca2+ handling, and, finally, the activation of profibrotic signaling, which would all promote arrhythmogenesis [18].

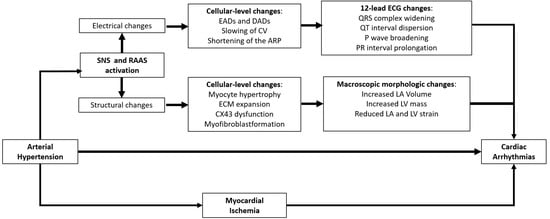

Furthermore, as displayed on Figure 1, the HTN-related activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAA) cascade and sympathetic nervous system (SNS), in addition to myocardial ischemia in hypertrophic hearts, would also play a major role in the pathogenesis of cardiac arrhythmias in HTN [19,20].

Figure 1. Electro-pathological and clinical changes occurring in hypertensive hearts. ARP, atrial refractory period; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; CV, conduction velocity; CX43, connexin 43; DADs, delayed afterdepolarizations; EADs, early afterdepolarizations; ECM, extracellular matrix; LA, left atrial; LA Vol, left atrial volume; LV, left ventricular; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. See text for further details.

3. Early Detection of Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertensive Patients: A Proposed Algorithm

Despite all efforts to prevent AF in hypertensive patients, structural heart disease and atrial cardiomyopathy in this setting would nonetheless cause progressive atrial derangement and electrical vulnerability, thus promoting a vicious cycle known as “atrial failure”, which is intimately connected with AF development [105].

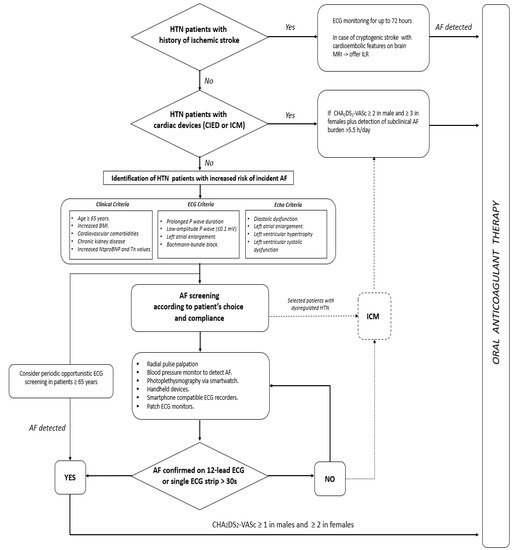

It is well known that AF is a potentially life-threatening cause of cerebral thromboembolism, and clinically silent forms might wreak even greater havoc if not recognised in a timely manner. For these reasons, hypertensive patients with an uncertain history of AF and evidence of prior cerebrovascular events should be accurately studied to differentiate strokes of cardioembolic origin from those secondary to atherosclerotic disease or cerebral haemorrhage [106]. In these cases, ECG monitoring can be helpful to identify patients with clinically silent AF [107,108], and, in the case of cryptogenic stroke, an implantable cardiac monitor (ICM) should be considered [10]. Over the last decade, cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) [109], ICM included [110], have proved extremely helpful in the early detection of subclinical AF episodes, but it is still debated which arrhythmic burden should prompt immediate oral anticoagulation in these patients. For the sake of clarity, clinically silent AF is defined for asymptomatic arrhythmia episodes detected on 12-lead ECG or an ECG strip; conversely, subclinical AF is represented by arrhythmia detected by CIEDs [10]. However, differentiating clinical from subclinical AF is not a matter of mere speculation. In fact, subclinical AF seems to portend a lower thromboembolic risk compared with clinical AF [111], and no clear cause–effect relationship between subclinical AF and ischemic stroke has been clearly proven in this setting [109]. However, the longer the duration of subclinical AF episodes, the greater their association with thromboembolic events [112]. For this reason, a recent European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document suggested oral anticoagulation administration for subclinical AF episodes longer than 5.5 h/day only when a significant risk of cerebral thromboembolism is established (i.e, CHA2DS2Vasc scores ≥ 2 and 3 in men and women, respectively) [111]. Whether this strategy pays off in terms of better clinical outcome is unclear. In fact, by randomising elderly patients with stroke risk factors and no AF history to the ICM strategy or usual care, the LOOP study did not prove the superiority of ICM over controls in terms of better clinical outcome after early AF detection [110]. Several issues raised by the same investigators might explain the overall negative results of this trial, such as the inadequate estimate of the primary outcome event rate, the relatively short duration of follow-up, and the initiation of oral anticoagulation for subclinical episodes lasting as low as 6 min. In keeping with prior observations [112], these results would suggest that not all subclinical AF episodes may benefit from early anticoagulation, and two ongoing randomized controlled trials might provide clearer answers in patients with CIEDs [113,114].

Moreover, in this already hazy scenario, it is all but crystal-clear which hypertensive patients with neither stroke history nor CIEDs/ICM should be screened for silent AF, and, not least, through which modality. On the one hand, the burden of cardiovascular comorbidities and blood biomarkers might play an important role in identifying people at a sufficient risk to warrant AF screening [115]. The thorough assessment of the P wave morphology on surface ECG may also be useful in identifying potential risk markers for AF, such as prolonged P wave duration, left atrial enlargement, and advanced interatrial (i.e., Bachmann bundle) block. [116]. Similar observation can be made for LVH, diastolic dysfunction, and left atrial enlargement as assessed on transthoracic echocardiogram [116]. However, what would be the best approach for AF screening in high-risk patients? On one side of the spectrum of the available modalities for AF screening, on account of the low cost and the great sensitivity yield, radial pulse taking should be regarded as the first option to be offered in patients aged ≥65 years and deemed at high risk of developing AF. Surface ECG analysis in the case of arrhythmic pulse is therefore warranted, and, if clinical AF is confirmed, oral anticoagulation should be promptly administered according to the patient’s thromboembolic risk profile [10]. Furthermore, a variety of screening technologies have been developed over the years and with progressively better AF detection accuracy [117], but no comparative trials have been carried out so far with any of these devices. Accordingly, European guidelines on AF diagnosis and management [10] strongly recommend a single-lead ECG tracing of ≥30 s or 12-lead ECG to confirm a diagnosis of clinical AF when detected by screening tools. Although similar observation can be applied to the use of ICM in the same setting, the positive clinical interaction observed in the LOOP trial between high blood pressure values and better clinical outcome in early anticoagulated patients in the ICM arm may prompt the use of an implantable loop recorder (ILR) as a screening tool in selected patients with HTN.

In conclusion, AF detection in its early stage is paramount, and an appropriate therapy might eschew severe complications potentially leading to disability and death in the affected patients. However, it should be ascertained which patients portend a greater risk of AF and thereby who should be screened for this arrhythmia and by which modality. While waiting for sounder results from ongoing clinical trials, Figure 2 provides a proposed algorithm for silent/subclinical AF detection and management in hypertensive patients.

Figure 2. Proposed algorithm for early detection and management of silent and subclinical atrial fibrillation episodes. AF = atrial fibrillation; CIED = cardiac implantable electronic devices; ICM = internal cardiac monitor; ILR = internal loop recorder; HTN = hypertension.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcdd9040110

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!