Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

To utilize host-derived nutrients, intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria have evolved a series of complex genetic pathways to metabolize human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs).

- infant-type bifidobacteria

- human milk oligosaccharides

- immune tolerance

- intestinal inflammation

- intestinal microecology

- immune-mediated disorders

1. Introduction

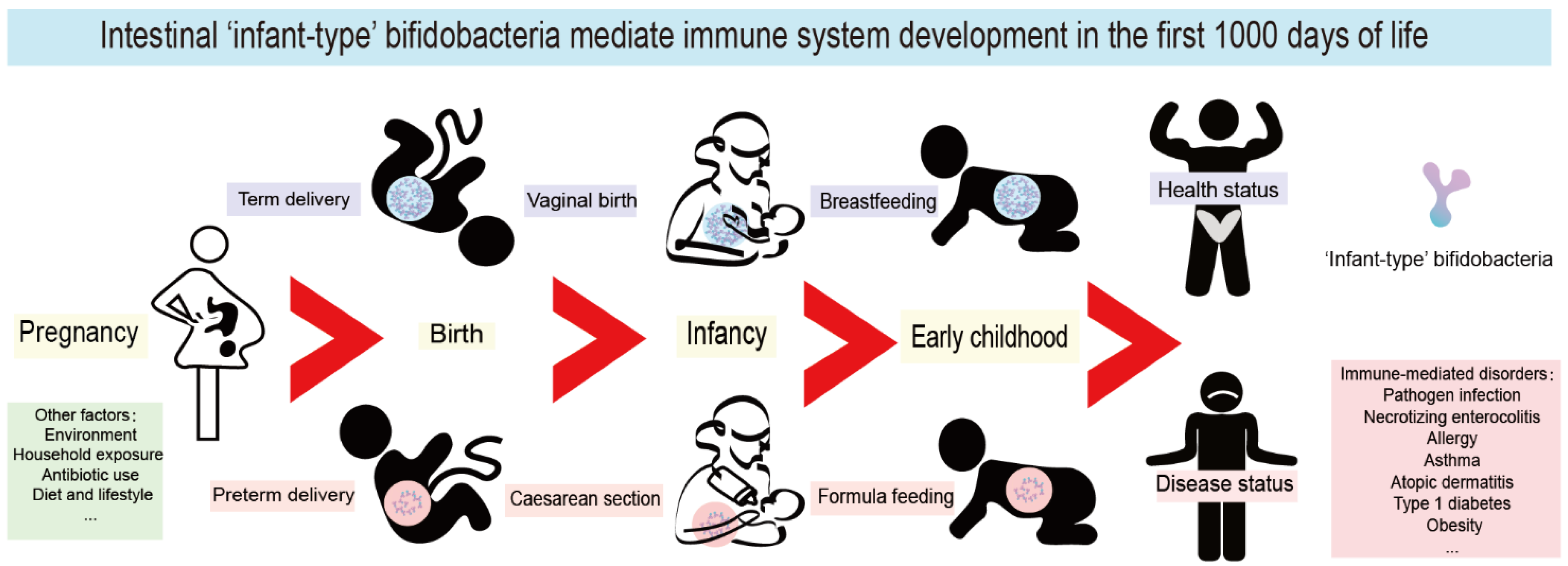

During the first 1000 days of life, immune system maturation and gut microbiota establishment occur concurrently, and this phenomenon has become one of the most exciting areas of immunological research. Due to potential microbiological contamination, it has not yet been possible to determine the exact bacterial composition of prenatal meconium [1,2,3]. However, it is well known that extensive microbial colonization begins rapidly after delivery [4]. In the first 1000 days of life, the gut microbiota of healthy breastfed infants is typically dominated by ‘infant-type’ bifidobacteria, including Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis (B. longum subsp. infantis), B. bifidum, B. breve and B. longum subsp. longum [5,6]. It is increasingly believed that the first 1000 days of life provide a critical window of opportunity for the shaping of the early immune system; thus, it might influence short-term and long-term host health by infant-type bifidobacterial colonization (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria mediate immune system development in the first 1000 days of life. The mode of delivery and feeding exert the most pronounced roles in the colonization of infant-type bifidobacteria in the first 1000 days. Pregnancy, environment, household exposure, antibiotic use, diet, and lifestyle all have a far-reaching impact on the composition of infant intestinal flora. Interfering with the colonization of infant-type bifidobacteria in early life leads to long-term and far-reaching health consequences, especially mediating the occurrence and development of a variety of immune-mediated disorders, including pathogen infection, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), allergy, asthma, atopic dermatitis, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) and obesity.

To utilize host-derived nutrients, intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria have evolved a series of complex genetic pathways to metabolize human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) [7,8]. This glycolytic activity leads to an anaerobic and acidic intestinal environment that stimulates immune development, controls pathogens, and affects the development of many organs (e.g., the liver and the brain) [9,10,11]. Moreover, a plethora of studies has provided evidence to support the association of the reduced abundance of infant-type bifidobacterial species with immune disorders in children or adults, such as pathogen infection, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), allergy, asthma, atopic dermatitis, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D), and obesity [12,13]. In addition, impaired microbiota development has been observed in preterm infants, infants delivered by cesarean section, and infants exposed to antibiotics in early life, which is often characterized by a reduced abundance of infant-type Bifidobacterium species [14,15]. Infant-type bifidobacteria are thus widely considered critical for the healthy development of the intestinal microbiota and immune system in the first 1000 days of life. Therefore, gut microbiome manipulation strategies are receiving increasing attention, especially those involving the generation or supplementation of infant-type bifidobacteria to help restore immune system development [9,16,17,18,19].

2. What Are the ‘Infant-Type’ Bifidobacterium Species and the Effect of Cross-Feeding?

The bifidobacteria isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract can be divided into two major categories: ‘adult-type’ Bifidobacterium species derived from the adult feces (including B. adolescentis, B. catenulatum and B. pseudocatenulatum), and infant-type Bifidobacterium species, encompassing other bifidobacteria that naturally inhabit the infant gut (including B. longum subsp. infantis, B. bifidum, B. breve and B. longum subsp. longum) [5,6,20]. B. longum subsp. longum is predominant in infant, adult, and elderly intestines [21]. Of note, B. longum subsp. longum is more common in formula-fed infants, while B. longum subsp. infantis is more common in breastfed infants [22]. Infant-type Bifidobacterium species possess genetic and enzymatic toolsets that are specific for HMO utilization; this confers upon them a growth advantage over other bacterial species, such as adult-type bifidobacteria and pathogens, enabling them to thrive in the intestines of infants in early life [7,8].

Notably, the utilization of HMOs by bifidobacteria shows species-specific differences. B. longum subsp. infantis possesses all the critical genes required for the complete internal degradation of HMOs and has been found to consume HMOs over other carbohydrates preferentially [8,23]. B. bifidum and B. breve are endowed with only very limited capabilities in utilizing HMOs [23]. It is evident that B. longum subsp. infantis is the most effective consumer of HMOs, and B. bifidum and B. breve can also partially consume HMOs, which are commonly found in breastfed infants [23]. However, B. longum subsp. longum and B. adolescentis mainly consume plant-derived, animal-derived, and host-metabolized carbohydrates, which results in their predominance in adults [8].

Moreover, certain Bifidobacterium species’ abundance in infants is associated with feeding patterns. HMOs are abundant in breast milk but are not or are very uncommon in infant formula [24]. Nowadays, HMOs are emerging in infant formulae to mimic natural human milk [25]. However, the infant formulae currently on the market, even the most premium ones, cannot provide the full range of HMOs [23]. More than 200 HMOs have been identified in breast milk, while only 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) are the two major HMOs applied to high-end and ultra-high-end infant formulae [25,26]. In addition, for many valid reasons, not all bottle-fed babies are fortunate enough to consume formula supplemented with HMOs [27]. As a result, most formula-fed infants are routinely not receiving adequate and abundant amounts of HMOs, which causes a decrease in the abundance of infant-type bifidobacteria.

Furthermore, the bifidobacterial population in the infant’s gut is composed of a co-group of multiple Bifidobacterium strains, rather than one strain dominating and competing to the exclusion of all others [28]. On the one hand, the cross-feeding effect among bifidobacterial species/strains is associated with the ability to thrive in HMOs of multiple Bifidobacterium members in the infant’s gut [29]. According to a study, the total abundance of Bifidobacteriaceae became very high when the abundance of B. bifidum exceeded 10% of the total microbiota in the feces of breastfed infants, suggesting the cross-feeding of HMO degraders in the bifidobacterial taxa [30]. It was found that B. bifidum SC555, as a fucose provider by hydrolyzing 2′FL, fulfilled the cross-feeding function of B. breve [31]. Although B. breve has no direct access to HMOs as a carbon source, host-derived monosaccharides/oligosaccharides could be vigorously consumed by the hydrolytic activity of other bifidobacteria [32]. In this context, the moderate growth of B. breve in total HMO and good growth in lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and LNnT were observed [33]. As a result, B. breve was isolated from the feces of breastfed infants at a high frequency. Similarly, B. pseudocatenulatum and B. kashiwanohense can barely consume HMOs and require further growth based on the degradation products of other bifidobacterial HMO utilizers [32]. On the other hand, certain bifidobacterial taxa cooperate with non-bifidobacterial taxa (including HMO consumers and non-HMO consumers) to maximize the nutrient consumption of HMOs, thus contributing to increased bifidobacterial diversity and dominance-gaining [29]. Considering the ability to digest HMOs, recent studies have confirmed that Lactobacillus, Bacteroides and Fragilis might also dominate the gut microbiota of infants to some extent [34]. Although other genera of neonatal intestinal microbiota (such as Clostridium, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus) cannot degrade HMOs on their own, partial decomposition products or fermentation end-products might be produced in combination with Bifidobacterium and/or Bacteroides [35,36]. Taken as a whole, this highlights the cooperation of the bacterial community in the neonatal intestine to maximize the utilization of HMOs, so as to maintain the intestinal immune balance of newborns.

This suggests a clear evolutionary link between infant-type bifidobacteria, neonatal immune systems and HMO metabolism. Overall, infant-type Bifidobacterium species are well adapted to the infant gut and efficiently consume HMOs, and their presence influences both immediate and long-term health outcomes.

3. Infant-Type Bifidobacteria Affect the Establishment of Immunity in Early Life

As mentioned, the first 1000 days of life provide a critical window of opportunity for immune system maturation, including the establishment of adaptive immunity and immune tolerance. During this period, the intestinal microbiome of the fetus and the infant undergo substantial development: from being in a near-sterile environment in the womb to being rapidly colonized by a large number of microbes at birth. There is mounting evidence that intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria are ideal probiotics for infants and are vital to early-life immunological development [9,59,60,61]. Herein, we discuss what is known about the role of intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria in establishing immune function in the early stages of life.

3.1. Infant-Type Bifidobacteria Occupy Intestinal Ecological Sites

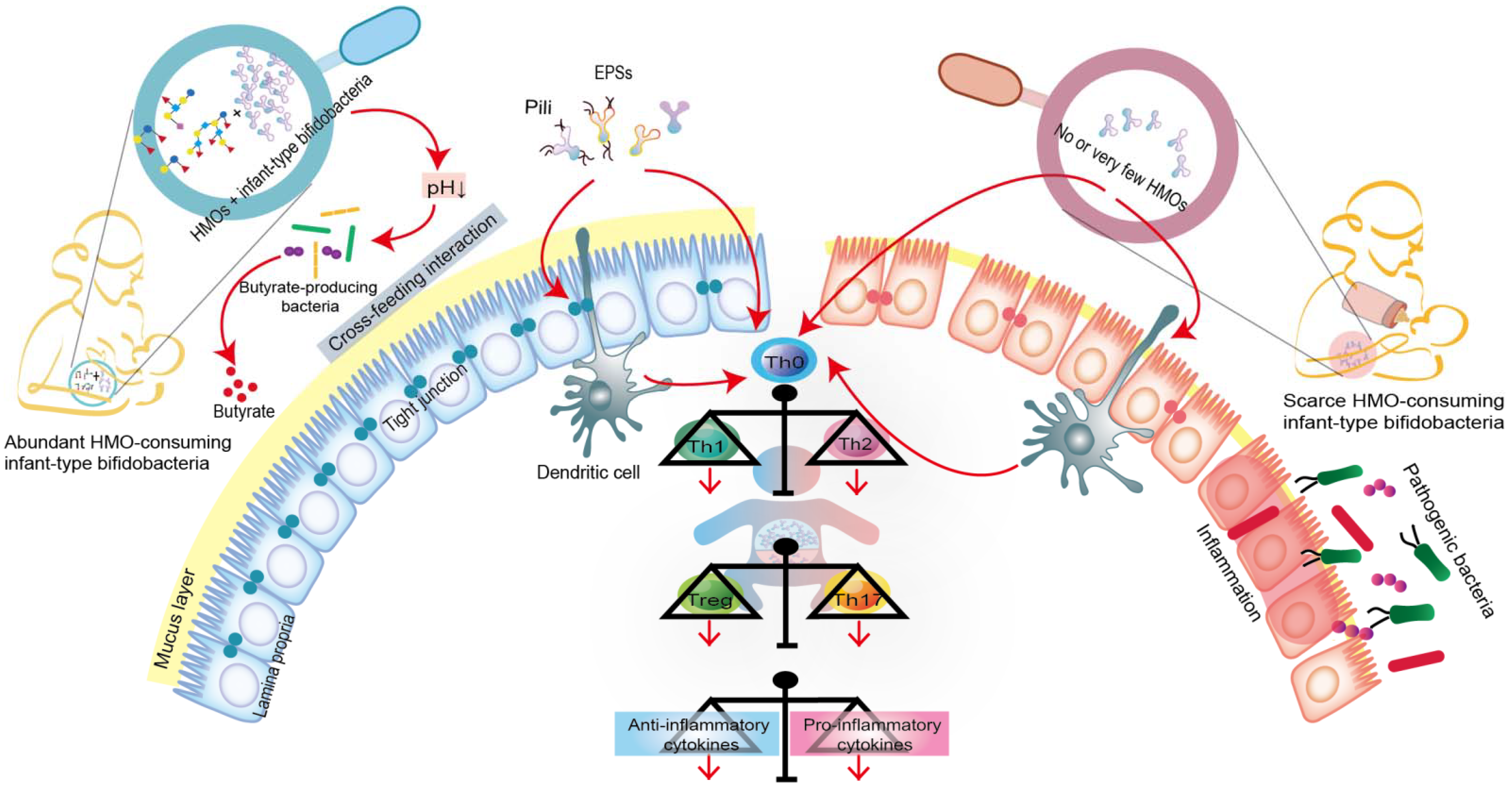

Humans cannot digest HMOs due to the lack of the necessary enzyme (glucosidase); this provides a selective nutritional advantage for the growth of beneficial bacteria that specifically consume HMOs [9,62]. Moreover, intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria, the main drivers of HMO metabolism, have evolved complex genetic pathways to metabolize the different glycans in human milk [7,8]. Intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria, therefore, have a competitive advantage in colonization over other gastrointestinal bacteria. In addition, the saccharolytic activities of bifidobacteria generate an anaerobic and acidic intestinal environment that protects the intestine from pathogenic infection. For example, compared to the stool samples of breastfed infants who received no supplementation, the stool samples from breastfed infants who were supplemented with B. longum subsp. infantis EVC001 exhibited a decrease in the abundance of Gram-negative Proteobacteria and Bacteroides and a four-fold decrease in the levels of endotoxin [17]. This indicates that infant-type bifidobacteria play a critical role in mediating immunity by occupying intestinal ecological sites and preventing pathogens from invading the intestine (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Co-evolution of intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria and HMOs-mediated immune system imprinting early in life. Breastfed infants are rich in intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria, which is significantly correlated with the increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines. In contrast, infants without breastfeeding have lower or no intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria, resulting in increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Although the exact mechanism is still elusive, infant-type bifidobacteria are widely considered to successfully modify the intestinal microecology in the early stages of life and prevent the progress of immune-mediated diseases, at least, by producing short-chain fatty acids (SAFAs), encoding extracellular structures (exopolysaccharides (EPSs) or/and pili), promoting cross-feeding effects, skewing T cell polarization, and promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

3.2. Infant-Type Bifidobacteria Facilitate Breast-Milk Metabolism

Infant-type bifidobacteria can affect host physiology in multiple ways, such as by regulating breast-milk metabolism. As mentioned above, it is now widely accepted that the co-evolution of infant-type bifidobacteria and the host immune system, mediated by HMOs, profoundly shapes early intestinal flora colonization and strongly influences the neonatal immune system. However, little is known about infant-type bifidobacterial metabolites, such as SCFAs, that mediate host-microbe interactions [63].

We focused on three common short-chain fatty acids (acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid) and lactic acid (also produced by gut bacteria and playing an important role in gut health) to learn how they contribute to gut health and immune development early in life. Infant-type bifidobacteria convert HMOs into acidic end-products (acetic acid and lactic acid) that affect fecal pH, reduce intestinal permeability, and increase the stability of tight junction proteins, all of which are characteristic of some intestinal diseases, such as NEC (Figure 2) [10,11,63]. Moreover, the acetic acid produced by infant-type bifidobacteria indirectly stimulates the growth, function and immune response of butyric acid-producing microorganisms through a mutually beneficial cross-feeding interaction (Figure 2) [64]. Butyric acid is the preferred fuel for intestinal epithelial cells, and its production further promotes the maintenance of intestinal barrier function by increasing mucin production and improving tight junction integrity [63,65]. In addition to their role in the intestinal tract, SCFAs produced by intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria can affect host physiology outside of the intestine, e.g., in the lung, brain, liver and adipose tissue [10,11]. For example, acetic acid, as the most abundant SCFA in the peripheral circulation, plays a direct role in central appetite regulation by crossing the blood-brain barrier and being absorbed by the brain, resulting in appetite suppression and hypothalamic neuron activation [10]. Although the concentrations of propionic acid and butyric acid are low in peripheral circulation, they indirectly affect the peripheral organs by activating hormone production and the nervous system [11].

Recent studies have also demonstrated the importance of aromatic amino acids, a type of metabolite produced by infant-type bifidobacteria, in early life [9,59]. Infant-type bifidobacteria produce large amounts of aromatic lactic acids, such as tryptophan-derived indole-3-lactic acid (ILA), in the intestinal tract of infants, through the action of aromatic lactate dehydrogenase [59]. Recently, ILA was shown to bind to both the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hydrocarboxylic acid receptor 3, regulate the response of monocytes to lipopolysaccharides, and block the transcription of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-8 [59]. ILA is also an anti-inflammatory molecule that can promote the development of immature intestinal epithelial cells [59]. Similarly, Henrick et al. observed that ILA produced by B. longum subsp. infantis silences the T helper cell 2 (Th2) and Th17 immune responses that are required to induce immune tolerance and inhibit intestinal inflammation during early life [9]. These new findings suggest that tryptophan metabolic pathways, particularly the ILA pathway, might be crucial for early immune development mediated by infant-type bifidobacteria, which maintains the inflammatory/anti-inflammatory balance of neonatal immunity, blocks the production of inflammatory cytokines and mitigates inflammatory damage.

3.3. Infant-Type Bifidobacteria Promote Immune Development and Prime the Anti-Inflammatory Gene Pool

As mentioned above, the immune system is immature in the early stages of life. Intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria represent one of the earliest antigens to activate the host defense mechanism, which helps to promote immune development and prime the anti-inflammatory gene pool (Figure 2). Recent studies have shown that infant-type bifidobacteria present different cell surface structures, such as exopolysaccharides (EPSs) and pili/fimbriae, allowing bifidobacteria to colonize the infant’s gut, adhere to intestinal cells and participate in the development of the host immune system [66,67]. Consequently, the administration of EPSs from B. breve UCC2003 might serve as a new strategy for promoting infant health [68]. In addition, EPSs produced by B. longum subsp. longum 35624 plays an essential role in inhibiting the pro-inflammatory response of the host (especially the local Th17 response), thus preventing inflammatory diseases [69]. Pili represent a fundamental cell-surface structure considered to be crucial in the interaction between Bifidobacterium and its host, and B. bifidum PRL2010 is equipped with the most functionally characteristic sortase-dependent pili [70,71].

Furthermore, the colonized intestinal microflora can trigger various immune responses by activating T cells and B cells in the intestinal mucosa. In the neonatal period, inflammatory responses are actively suppressed. This phenomenon occurs because neonatal T cells have an internal mechanism wherein the immune system develops toward the characteristics of sensitizing Th2 cytokines, while Th1 cell proliferation and interferon-γ production are inhibited (Figure 2) [38,72]. A recent study showed that the absence of bifidobacteria in the gut flora of newborns leads to the activation of innate and adaptive immunity, which increases the populations of neutrophils, basophils, plasmablasts and memory CD8+ T cells [9]. Additionally, intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria affect the intestinal Th cell response, especially that of Th0 and Th17 cells [9]. In particular, these bifidobacteria stimulate the early immune response for defense while avoiding the overactivation of Th2 and Th17 responses [9]. This study found that the increase in infant-type bifidobacteria abundance is positively associated with a decrease in pro-inflammatory markers (such as memory Tregs and pro-inflammatory monocytes) and an increase in inflammatory markers (such as Tregs, IL-10 and IL-27) [9]. Another study showed that the growth of HMO-consuming B. longum subsp. infantis stimulates the activity of the intestinal epithelium via T cells [61]. Specifically, B. longum subsp. infantis, grown on HMO, increased the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in Caco-2 cells and the expression of junctional adhesion molecules and occludin in Caco-2 cells and HT-29 cells [61]. Furthermore, the infant-type bifidobacteria might affect T cells directly or indirectly, via dendritic cells [66,73]. Recent research provides new evidence of the crucial role of breast milk in promoting neonatal Bifidobacterium colonization and B cell activation [74]. It shows that core-fucosylated N-glycans in the mother’s milk selectively promote the colonization of bifidobacteria in infants, whereas their absence from the mother’s milk reduces the proportion of spleen CD19+ CD69+ B cells in offspring mice. In vitro studies also found that the L-fucose metabolites, lactic acid and 1,2-propanediol promote B cell activation through the signaling pathway mediated by B cell receptors [74].

3.4. The Potential Role of Infant-Type Bifidobacteria in Early Neuroimmune Development

Recent studies have emphasized the potential role of intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria in neuroregulation in early life [75,76]. A growing body of evidence supports that the gut-brain connection already exists at birth and enables the gut microbiome to interact with and affect the central nervous system [75,76]. The accumulated data show that neonatal intestinal microbial colonization activates the immune system, sends signals to the central nervous system through the afferent vagus nerve, and produces microbial metabolites (SCFAs, such as acetic acid) that can directly or indirectly affect brain function [75]. Thus, the intestinal microbiota that colonizes infants during their early life shapes the steady-state development and balance of postnatal neural connection [75]. Intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria might also shape host neural circuits by regulating synaptic gene expression and microglial functionality during postnatal development [75]. Currently, however, there is limited information on the mechanism by which gut microbes communicate with the host brain. Further studies are warranted to further clarify the effects of infant-type bifidobacteria on brain function and the underlying mechanism of their action in newborns.

In short, intestinal infant-type bifidobacteria trigger immunomodulatory responses through multiple mechanisms to maintain host health (Figure 2). For example, bifidobacteria occupy the microbial nutritional niche in the gut, release metabolic by-products of HMOs either directly or indirectly (cross-feeding interaction), present extracellular structures (such as EPSs and pili) that interact with host cells, and inhibit inflammatory responses, including intestinal Th cell responses and B cell-induction responses. Observational studies have confirmed a link between the loss of infant-type bifidobacteria and early intestinal inflammation, although little is known about the underlying mechanisms [9,59,76,77].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14071498

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!