Multiple myeloma (MM) remains an incurable malignancy with eventual emergence of refractory disease. Metabolic shifts, which ensure the availability of sufficient energy to support

hyperproliferation of malignant cells, are a hallmark of cancer. Deregulated metabolic pathways have implications for the tumor microenvironment, immune cell function, prognostic significance in MM and anti-myeloma drug resistance. Herein, we summarize recent findings on metabolic abnormalities in MM and clinical implications driven by metabolism that may consequently inspire novel therapeutic interventions. We highlight some future perspectives on metabolism in MM and propose potential targets that might revolutionize the field.

- multiple myeloma

- metabolism

- metabolic vulnerability

1. Introduction

Metabolic Deregulations Predict Adverse Prognosis in MM

2. Physiological Role of Metabolism in Plasma Cells

3. Current Literature of Metabolic Abnormalities in MM

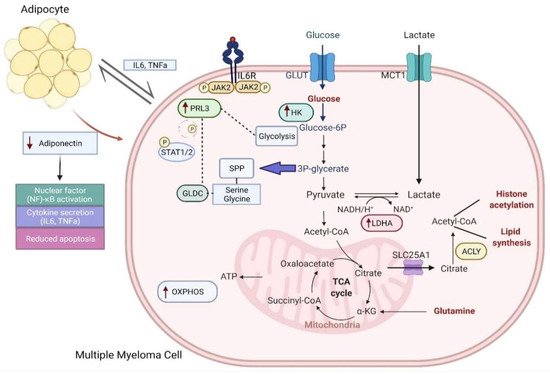

3.1 Myeloma Cells Undergo Metabolic Rewiring of Glycolysis and Mitochondria OXPHOS

3.2 Fatty Acid Metabolism Obesity as a Risk Factor in Myeloma

The role of bone marrow adipocytes (BMA) in supporting myeloma cells is relatively under-explored despite its dynamic functions. Its multifaceted roles include endocrine secretory functions, promoting cell-to-cell communication directly, correlating with obesity, a possible role in bone disease and close proximity to myeloma cells [22][23][24][25]. BMAs may potentially supply free fatty acids to MM cells for proliferation and survival. This has implications on fatty acid metabolism including fatty acid uptake and oxidation[26]. Myeloma cells have elevated levels of fatty acid-binding proteins (FABP), which potentially enhances tumor growth[27]. Furthermore, Etomoxir, an inhibitor of fatty acid beta oxidation and orlistat, an inhibitor of de novo fatty acid synthesis, ameliorated myeloma proliferation and decreased MM survival [28].t(4;14)-positive cells showed a high dependency on the mevalonate (MVA) pathway for survival. Inhibition of the fatty acid synthesis pathway with statin specifically increased apoptosis in this subset of cells. Furthermore, statin treatment led to an activation of the integrated stress response (ISR), which was modulated by co-administration with bortezomib. Evidence from exogenous rescue using geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) showed that t(4;14)-positive cells require the MVA pathway for the synthesis of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). Interestingly, fluvastatin treatment had synergistic effects with bortezomib in vivo[29].

Obesity is a critical component of metabolic syndrome and contributes to MM pathogenesis heterogeneously. It is often measured based on body mass index (BMI) and classified into three unique stages by the World Health Organization: stage 1 (BMI 30–34.9), stage 2 (BMI 35–39.9) and stage 3 (BMI ≥ 40) [30]. Obesity-related epidemiological findings are deeply concerning and associations to multiple cancers including MM have been reported. Wallin and Larsson meta-analyzed 19 prospective studies which consistently demonstrated statistical significance between increased MM incidence and overweight individuals [31]. Indeed, excessive body weight has been highlighted as a critical risk factor for MM progression and mortality, which is well-supported by multiple studies[32][33]. Consequently, obesity has been established as a risk factor for MM by the International Agency for Research on Cancer recently[34]. It has also been proposed that the myeloma disease burden could be reduced at the population level with obesity accounted as the sole modifiable risk factor[8].

4. Clinical Implications of Metabolic Deregulation in Myeloma

Rewired metabolism attenuates the therapeutic effects of standard-of-care drugs, largely attributed to the hypoxic tumor microenvironment in the bone marrow (BM) [36]. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1 is activated in this context, which drives glucose metabolism towards dependency on pyruvate conversion to lactate, rather than its oxidation in the mitochondria for energy production[20]. It has been postulated that drug resistance might arise through the adaptation to hypoxia in the BM, leading to relapse. Upregulation of HIF-1 and HIF-2 pathways was shown through an analysis of gene expression datasets comparing primary MM patients and healthy subjects. Importantly, a further enrichment of these pathways was evident in bortezomib-refractory and relapsed myeloma patients [37][38]. Human myeloma cell lines (HMCLs) subjected to hypoxic conditions and thereafter treated with bortezomib, dexamethasone and melphalan were observed to have increased glucose metabolism, with and overexpression of LDHA and HIF-1 post-treatment[20].

4.1 Metabolic Deregulation Attenuates Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is presently used for treatment in MM. The array of therapeutics used in MM includes immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), inhibitors of immune checkpoint, vaccines derived from dendritic cells and allogenic transplantation[39]. IMiDs potentiate the proliferative and functional properties of natural killer (NK) and NK T cells. Additionally, both daratumumab, a CD38 monoclonal antibody, and immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown to enhance T cell immunity against myeloma [40]. Other immunotherapeutic strategies include the dendritic cell (DC) vaccine synthesized by DC fusion with antigen and the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy which modifies autologous T cells genetically with CAR expression and the specific target of tumor antigens [41].

Despite the promising potential of immunotherapeutic strategies, they come with their own set of challenges in the context of metabolism. Alterations in metabolism in the tumor microenvironment can weaken the therapeutic effect of immunotherapy[42]. The TME confers metabolic privileges to tumor cells by increasing the rate of glucose and glutamine uptake and by excessive lactate production and secretion. This metabolic shift is unfavorable for T cell recruitment and for them to thrive, because of nutrient deprivation, extensive acidification, a build-up of waste products and hypoxia[43]. Through pH buffering with bicarbonate, the acidification of the TME could be circumvented and the efficacy of immunotherapy improved. This could potentially be applied in MM. Although 2-Deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) is used in MM to inhibit glycolysis, it is incompatible with coadministration of immunotherapeutic agents as it impairs T cell metabolism and reduces its antitumor effects[42]. Immune cells primarily metabolize amino acid, such as L-arginine, which is a non-essential amino acid found in macrophages and DCs. However, lactate secretion by tumor cells leads to an overexpression of arginase, which converts L-arginine to urea and ornithine and, consequently, an impairment of T cell function by interference with cell cycle progression. MM cells are known to secrete lactate and it can be reasonably postulated that MM cells can cause T cell dysfunction through this mechanism [44].

.This entry is adapted from 10.3390/cancers14081905

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14081905