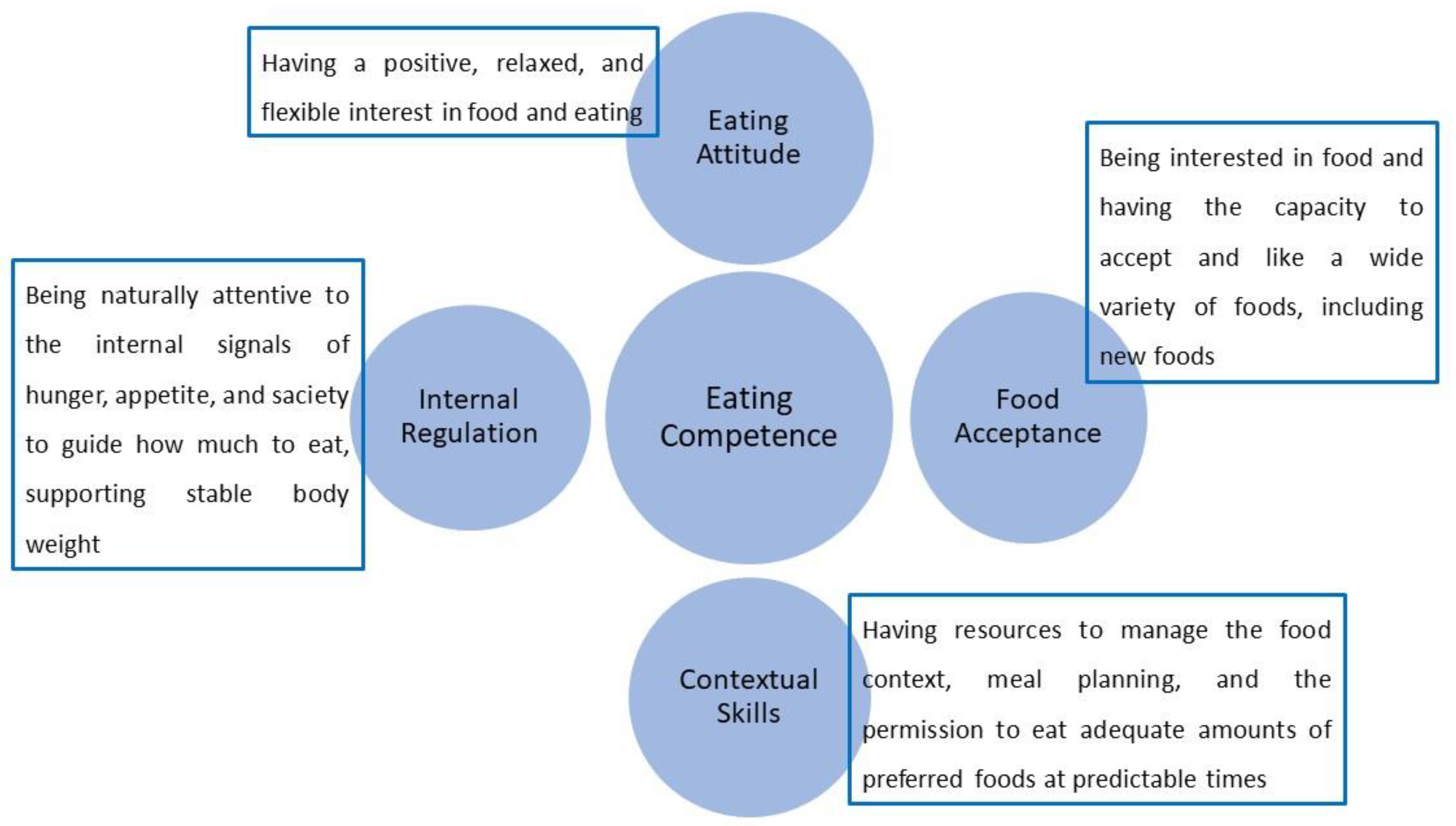

Eating Competence (EC) is the successful result of the four proposed components

[1] described below and summarized in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. The four components of Eating Competence.

1.1. Eating Attitude

Eating attitude involves the beliefs, thoughts, and feelings that lead to behaviors that affect how individuals relate to food and influence food choices and, consequently, health

[2]. The construction of eating attitude begins in childhood and is an aspect of great relevance for health promotion

[3]. According to the concept of eating competence, the ideal eating attitude refers to being positive about food and eating, that is, enjoying eating and feeling comfortable about it

[4], as well as having an interest in food, and showing self-confidence and tranquility concerning their food choices

[5].

Excessive worries about food and eating, whether for aesthetic or health reasons, favor the development of distorted beliefs and feelings about food, leading to the continuous manifestation of a negative eating attitude

[6]. In turn, these can lead to the search for an eating pattern out of the individuals’ reality

[7][8][9][10]. In addition, individuals with negative attitude toward food and eating are more likely to demonstrate body dissatisfaction, as those who usually feel “very fat” or “very thin” or simply uncomfortable with their weight are more likely to feel ashamed of what they eat

[4].

A New Zealand study on food habits and body weight (

n = 294) found a significant link between the desire to lose weight and the belief in the association between chocolate cake and guilt. Participants who felt guilty about eating the cake had more difficulty maintaining or losing weight than those who associated the cake with celebration

[11]. The association of chocolate cake with festivity was linked to better weight maintenance, consistent with the eating attitude proposed in the ecSatter model

[7][12], emphasizing the relevance of eating attitude in food selection and health.

In 2006, a telephone survey with a representative sample of the American adult population (

n = 2250) showed that individuals who consider themselves overweight report a lack of pleasure associated with eating compared to individuals who feel good about their body weight

[13]. Six out of ten adults affirmed that they eat more quantity than they should. However, this type of statement was associated with behavioral aspects, being more present among individuals with higher scores on the stress assessment scale, among those who were overweight, who reported some concern with weight, or who were dieting to lose weight

[13]. It is not possible to determine whether this judgment concerning overeating is a genuine result of high food consumption or whether it is a personal impression resulting from strict norms regarding body weight, food, and health.

EC is associated with relevant behaviors in the context of nutritional health, such as greater satisfaction with body weight and a lower frequency of behaviors associated with eating disorders

[1][8][14][15][16]. Body dissatisfaction seems to be a risk factor for overweight and eating disorders

[15]. Queiroz et al. noticed that Brazilian adults who thought their body size was acceptable had higher EC scores than those who thought it was excessive (EC total score = 33.63 ± 7.56 vs. 27.7 ± 9.02;

p < 0.000)

[17]. Other studies on EC found a link between EC and body satisfaction. For example, among American college students (

n = 1720), body mass index (BMI) was not as good a predictor of EC as weight satisfaction and desire to decrease weight

[14]. Among low-income women, the lowest EC score is related to body weight dissatisfaction, a proclivity to overeat in reaction to external emotional stimuli, and eating disorder-related behaviors

[1]. In a survey of 557 university students enrolling in an introductory nutrition course, researchers discovered that individuals who had never had an eating disorder had a higher average ecSI score than those who had a present or past eating disorder

[16].

Eating-competent individuals usually tend to have less body dissatisfaction and less expression of weight control, as well as lower psychosocial characteristics related to disordered eating, fewer food dislikes, and greater food acceptance

[15]. As EC increased, decreases were observed in the tendency towards bulimic thoughts, drive for thinness, and body dissatisfaction

[15]. Regarding Eating Attitude, this component was inversely associated with restrained eating, body dissatisfaction, and desire to be thin

[15]. Bulimic thoughts and feelings of uncontrolled hunger significantly increased as internal regulation decreased

[15].

1.2. Food Acceptance

The sensory characteristics of food, especially the taste, are identified determinants of food intake

[18]. However, according to the EC concept, enjoyment and pleasure are important motivators for food selection

[4].

Food choices are inserted in the priority order of human needs that can be understood from the perspective of Satter’s Hierarchy of Food Needs

[19]. According to this proposal, the first basic need is to have enough food, which means food security from an economic and social standpoint. In this first level, individuals are driven by hunger and anxiety about getting enough to eat. The second need considers the subjective issue of acceptability, linked to food culture, social norms, and rules. In third comes the guarantee of having food availability for the next meals, indicating the possibility of planning the stock and budget for foods purchase. Following the hierarchy, the flavor comes fourth, after the first three basic needs are satisfied, and then the possibility of opening up new food experiences and eating unfamiliar foods. Finally, after all the above needs are met, the individual can consider instrumental reasons, such as searching for physical results (health and/or aesthetic) or cognitive and spiritual reasons

[19]. At each level, needs must be satisfied before those at the next higher level can be experienced and addressed. The first three stages of the food need hierarchy are linked to issues involving the concept of Food and Nutritional Security

[20].

Individually, the tendency to make food choices can be triggered by relatively simple stimuli, such as the content of sugar or fat in the food, the individual’s gastric capacity, the size of the portion presented, and even how much others eat

[21]. However, external aspects affect those neurophysiological mechanisms, causing sensations such as pleasure and satiety, which are exacerbated or inhibited through logical reasoning about the consequences related to weight and health

[21]. Moreover, concerning external issues, it is important to consider the various environments that influence food choices, as these environments make food available to the consumer

[22]. In this sense, daily contemporary life is characterized by the abundance of attractive and energy-dense foods, which, combined with less need for physical activity, results in an “obesogenic” environment

[21]. In many contemporary societies, some foods have become almost universally available and accessible, being purchased in many places, at any time, and by anyone

[3][20][23]. The profusion of eating opportunities leads individuals to make numerous choices throughout the day, including the choice not to eat

[12].

The acceptability of food is also related to the affective and symbolic value that the food represents, influencing the construction of preferences and aversions

[3][20]. The taste construction and food preferences is a process that starts in early childhood; thus, the adequate development of this skill depends on the feeding practices from an early age. In this sense, among the feeding behaviors, it is recommended that the diet of the infant or young child be diversified, with repeated exposure to healthy foods and drinks, avoiding the offer of foods rich in salt, sugar, and flavor additives to provide the construction of healthy food preferences

[24].

1.3. Internal Regulation

This component is related to identifying the physical signs of hunger, appetite, and satiety, which will guide the amount of food to be eaten to contribute to the natural maintenance of healthy and stable body weight

[4]. People with better internal regulation tend to have more regular meals, as they are naturally aware of the signs of hunger and can maintain a predictable rhythm of meals

[25]. In addition, internal regulation allows confidence in the experience of satiety, which contributes not only to weight stability but also to satisfaction with the body shape

[5]. Internal regulation is part of the central idea of intuitive eating and is also highlighted in mindful eating, as the improvement in awareness of internal and external experiences allows the individual to make more rational and less impulsive choices

[7].

Internal regulation was linked to BMI, body size perception, and food consumption among Brazilian adults

[4][5]. The absence of internal regulation is linked to the inability to recognize sensations related to hunger/satiety, as well as bulimic thoughts and feelings of uncontrollable hunger

[15].

According to studies, a lack of EC is linked to bulimic thoughts, a feeling of uncontrollable eating, and a higher frequency of binge-eating episodes

[1][15]. Generally, the more subtle bodily sensations happen automatically and, when such sensations are ignored, the signs of hunger and satiety end up being perceived later, when they are exacerbated

[26]. This leads the individual to experience extremes of hunger and fullness. People who become used to external control over the amount they should eat—for example, restrained eaters and individuals who are dieting—may feel unable to trust their own ability to decide how much to eat

[4]. Eating disorders can be triggered by dieting, but are not caused by it; however, it seems that self-imposed dietary restrictions are associated with lower levels of internal regulation

[15].

1.4. Contextual Skills

Food choices are situational and part of a process that requires multiple and interrelated decisions

[12], e.g., a decision regarding what to eat is frequently tied to where to get it and how to prepare it, and a purchase decision might be linked to additional considerations including where to maintain food and how to deliver it

[12]. In this sense, eating involves a series of actions and behaviors that include a variety of food handling steps, each of which requires distinct decision-making procedures, such as acquiring, preparing, and changing raw materials into meals

[12].

In the ecSatter model, this component is linked to the ability to manage the food context, that is, develop food shopping strategies, plan meals, have cooking skills that enable food autonomy, and manage the time dedicated to preparing and consuming meals

[5][15].

Food preparation skills have been positively associated with diet variety, increasing diet quality

[27][28]. Cooking contributes to a healthier diet as it develops multiple knowledge about the different properties of food, making the cook acquire a conscious and objective attitude towards food, favoring the preparation of palatable, attractive, and good quality meals

[21].

To minimize the replacement of fresh foods and regional culinary preparations by industrialized and ready-to-eat products, food systems should aim to preserve food cultures, encouraging the development of culinary skills to favor the consumption of artisanal and homemade meals

[29]. The habit of cooking and preparing meals at home has shown a positive association with EC and healthy eating. Krall and Lohse, in a study to validate the ecSI with American women (

n = 507; 18–45 y/o), found a positive relationship between EC and the habit of cooking at home. In addition, women classified as competent eaters (EC ≥ 32) reported that they like to cook and demonstrated more practical skills in managing their meals, including healthy aspects in food planning. As expected, women with greater contextual skills had lower BMI and presented a higher intake of fruits and vegetables (FV)

[1]. Among Brazilian adults (

n = 1810; 75% female), the contextual skills were positively associated with education level, age, BMI, food consumption, and income

[30].

An American survey that interviewed 764 men and 946 women between the ages of 18 and 23 showed that those who reported more frequent preparation of their meals consumed amounts of fat, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and calcium closer to dietary goals

[31]. A recent Brazilian study showed that parents with autonomy and confidence in their cooking skills provide their children with a diet with fewer artificial and ultra-processed foods, indicating the importance of managing the food context in promoting the individual’s and families’ nutritional health

[32]. Previous studies have revealed that parents with cooking practice behaviors play an important role in mediating their children’s consumption of FV

[33][34].

According to Taylor, pleasure in eating is associated with pleasure in cooking

[13]. To improve diet quality, interventions among young adults should invest in teaching practical and healthful food preparation skills

[31]. Therefore, the development of food preparation skills using cooking classes has been considered a way to develop healthy eating and enable people to combine healthy habits with a wider variety of meals, resulting in increased independence in the implementation of healthy behaviors

[7][35].

The ability to manage the food context proved to be especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic, where routines were entirely changed. A cross-sectional study performed in Brazil from 30 April to 31 May 2021 among a convenience sample of the Brazilian adult population (

n = 302; 76.82% female) found that the measure of the contextual skills component decreased after the pandemic among those who gained weight (9.56 ± 3.43vs. 7.50 ± 3.95;

p < 0.005); those who decreased the consumption of vegetables (9.78 ± 2.79 vs. 6.63 ± 3.40;

p < 0.005), and those who increased the consumption of sugary beverages (9.19 ± 3.16 vs. 6.92 ± 3.70;

p < 0.005)

[36]. Moreover, individuals who used to buy ready-to-eat meals during the pandemic showed a reduction in total EC and all components (

p < 0.005). On the other hand, there was no reduction in the contextual skill component among those who reported the habit to prepare their food

[36].

2. Eating Competence Inventory

EC can be evaluated using the Satter Eating Competence Inventory (ecSI™2.0), a tool consisting of a 16-item self-administered questionnaire that assesses overall EC and its four components: eating attitude, composed of six items; food acceptance (three items); internal regulation (two items); and contextual skills (five items)

[37].

Items are answered with the options: always; often; sometimes; rarely; and never. The score is obtained by the sum of the answers (always = 3; often = 2; sometimes = 1; rarely = 0; and never = 0), thus, the scores of the ecSI2.0™ can range from 0 to 48

[38]. The cutoff for the definition of eating competence is 32 and above

[15][38]. The higher the ecSI2.0™ score, the higher the eating competence. There is no defined cutoff point for each of the four components

[38]. However, in individualized approaches, to the extent that the score is deficient in one of the four components, it is possible to predict which skill the individual needs more attention and reinforcement.

The ecSI

[39] was initially validated in 2007 with a sample of 832 US adult respondents (mean age 36.2 ± 13.4 years) without eating disorders, 78.7% female, white, educated, overweight, physically active, and food secure, providing support of content and construct validity, as well as internal consistency

[15]. Its reliability was examined with 259 white females (26.9 ± 10.4 years), mostly food secure, with some college education, providing psychometric evidence about the reliability of the ecSI to measure EC but suggesting the revision of some items, as individuals with lower income tended to score lower on the ecSI

[39]. In 2011, researchers revised the tool and made changes in the text of four items to favor the understanding of the content by individuals with lower income

[1]. Construct validity of this instrument was demonstrated in a larger sample of 507 low-income women

[1], aged 18 to 45 y/o, and results originated the ecSI/Low Income (ecSI/LI)

[1]. The ecSI/LI was tested again in 2015 with 127 adults (35.8 ± 5.3 years) and proved to also be valid for higher-income groups

[40]; this tool was named ecSI2.0™. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted by Godleski et al., to affirm factor structure resulting in the movement of one item from the Internal Regulation to the Eating Attitude subscale in the current version of the inventory (ecSI2.0™)

[37].

Investigators and educators, under permission, can use the ecSI2.0™ to investigate the EC construct and track intervention outcomes with individuals of different levels of income and education

[38]. Originally formulated in English, the ecSI2.0™ is translated into German, Arabic, Finnish, Japanese, Estonian, Spanish

[41], and Brazilian-Portuguese

[30].

3. Eating Competence and Health

EC has been evaluated in several countries and is associated with health indicators, such as food consumption, maintenance of body weight, and the occurrence of diseases, and factors related to other health aspects, such as sleep quality, physical activity, stress management, and behaviors linked to eating disorders.

3.1. Eating Competence and Diet Quality

Despite not focusing on quantities or specific nutrients, the EC behavioral model is associated with diet quality

[4]. Diet quality refers to the degree of adequacy of a dietary pattern compared to recommendations for healthy eating. Such recommendations are defined based on minimum parameters so that the diet provides all the necessary nutrients to promote and maintain health

[42][43]. Among the dietary patterns explored in studies on EC, the consumption of FV is highlighted, following the recommendations for healthy eating

[20][44]. The intake of FV is considered adequate when the usual rate is a minimum of five servings a day, totaling 400 g/day

[45].

Positive associations between EC, food acceptability, and FV consumption have been described. For example, an American study, carried out with a convenience sample of 863 adults, compared the ecSI score with the responses of other instruments to investigate aspects of eating behavior, food acceptability, FV consumption, and sociodemographic data

[15]. Among the instruments used, there were two related to food consumption and diet quality: Food preference survey (is an alternative to food frequency surveys, with a list of 62 food items, judged on a scale ranging from “dislike extremely” and “like extremely” with separate choices for “never tried” or “would not try”); and Fruit and vegetable stage of change algorithm (measures the stages of change—pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance—for FV intake through responses that indicate the current intake and the intention to modify it). Regarding food consumption, individuals in the pre-contemplative stages of increased consumption of FV had lower scores on the ecSI than those who were already in the action and maintenance phases. Individuals with higher ecSI scores also had greater food acceptability and fewer dietary restrictions than those with lower EC

[15]. The positive association between EC, food acceptability, and FV consumption was also confirmed in subsequent studies with low-income women

[1][46][47]. EC also showed a positive association with diet quality in another study with American women (

n = 149; age 18–50 y). Through a telephone interview, the researchers collected three days of 24 h dietary recall and the ecSI on the third day of the interview. The results showed that women classified as competent eaters (ecSI scores ≥ 32), had higher ingestions of fiber and vitamins A, E, C, and complex B, as well as magnesium, zinc, iron, and potassium. This research divided the group of women according to dietary patterns. The Prudent pattern, defined by the consumption of nutritious foods such as FV, and low-fat dairy products, was more prevalent among women classified as competent eaters. On the other hand, the Western pattern, associated with fatty, salty, and sugary foods, was observed more among women with lower scores on the ecSI

[1][25].

A study in Brazil that looked at the relationship between EC and food intake and health outcomes among adults (

n = 1810; 75% females) found that FV ingestion was strongly related to overall EC and its components

[30]. The findings show that EC is linked to higher consumption of FV, which is related to improved health and protection against overweight

[30].

3.2. Eating Competence and Risk Factors for Overweight and Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases (NCDs)

Overweight and obesity are important risk factors for developing NCDs, so the control and maintenance of an adequate weight have been recommended as a health goal. Lohse et al.

[15] observed the relationship between EC and BMI in the ecSI validation research, with 863 healthy adults, aged between 18 and 71 years. On that occasion, individuals from the group of competent eaters reported a smaller lower percentage of BMI ≥ 25 compared to those from the group of non-competent eaters

[15]. This association was also found in another study with low-income North American women, in which a lower ecSI score was related to a higher BMI

[1]. A sampling of the adult population in Brazil yielded similar results (

n = 11,810; 75% females) with high educational levels and high income, where eating competent individuals showed smaller BMI than non-eating competent ones

[17].

The research with a sub-sample of 638 elderly participants at cardiovascular risk participating in the Spanish clinical trial Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) showed that individuals classified as competent eaters had lower BMI, higher High-density Lipoproteins (HDL), lower Low-density Lipoprotein (LDL), and lower fasting glucose rates, and participants with higher EC, despite reporting higher caloric intake, had lower BMI

[48]. The association between EC and cardiovascular risk biomarkers was also documented in a smaller sample (

n = 48), composed of men and women between 21 and 70 y/o, with dyslipidemia. Subjects classified as non-competent eaters had considerably higher levels of triglycerides and LDL compared to the competent eaters’ group

[49]. In a Finnish study with participants in the StopDia (Stop Diabetes) survey, EC was linked to a lower rate of type 2 diabetes, visceral obesity, metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridemia, and greater insulin sensitivity

[50]. These findings support the hypothesis that developing skills that increase EC may be a strategy to help control body weight, prevent metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, and may help to prevent type 2 diabetes in the long term

[50].

3.3. Eating Competence and Health-Related Aspects

Additional health-related aspects, including sleep quality and physical exercise, also show some association with EC. For example, individuals with higher EC tend to perceive themselves as being physically more active

[15][51], and the relationship between low EC and low levels of physical activity is reported among low-income women

[1].

Regarding sleep quality, a study with young university students found that overweight and obesity were linked to poor sleep quality and low EC, with results maintained after adjustments for the sociodemographic variables of the sample

[52], suggesting that obesity prevention interventions for college students should include education components to improve EC and emphasize the importance of sleep quality

[52]. Another research with university students evaluated the association between the number of sleep hours and EC, comparing students that slept eight hours or more per night with those who slept less than eight hours. The results show that those who slept less had even more poor eating habits, weaker internal food regulation, and more binge eating behaviors

[53].