Asexual Epichloë are obligate fungal mutualists that form symbiosis with many temperate grass species, providing several advantages to the host. These advantages include protection against vertebrate and invertebrate herbivores (i.e., grazing livestock and invertebrate pests, respectively), improved resistance to phytopathogens, increased adaptation to drought stress, nutrient deficiency, and heavy metal-containing soils. Selected Epichloë strains are utilised in agriculture mainly for their pest resistance traits, which are moderated via the production of Epichloë-derived secondary metabolites. For pastoral agriculture, the use of these endophyte infected grasses requires the balancing of protection against insect pests with reduced impacts on animal health and welfare.

- alkaloids

- animal toxicosis

- biocontrol

- endophyte

- fescue

- ryegrass

Microbial endophytes, primarily comprising archaea, bacteria, fungi, or viruses, are associated with most plant species [1][2]. The term ‘endophyte’ was derived from the Greek words ‘endon’ (within) and ‘phyton’ (plant) [3], and initially included both pathogenic and beneficial microorganisms [4]. However, the term endophyte has now become synonymous with mutualism in reference to microbes that spend all or part of their life cycle within the plant host while causing no apparent disease symptoms [5][6], and provides a net benefit outcome to both itself and the host plant [7].

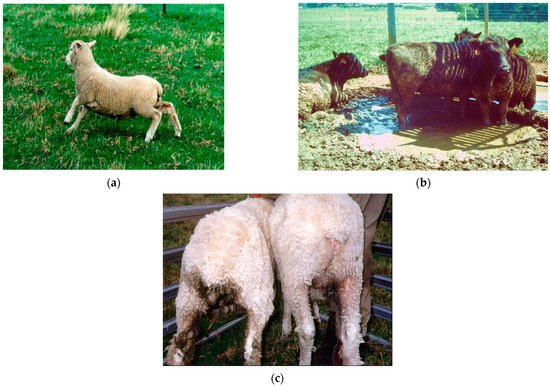

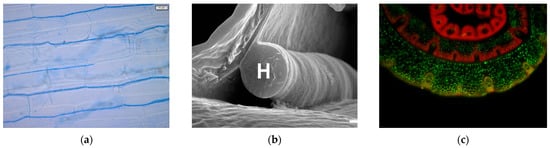

Asexual Epichloë endophytes (previously belonging to the taxonomic genus Neotyphodium [8]) were identified in the 1980/90s as the cause of two economically important diseases that affected livestock that grazed fescue in the USA and perennial ryegrass in New Zealand, namely fescue toxicosis [9] and ryegrass staggers [10], respectively (Figure 1). These obligate symbionts are mutualistic, relying on the host plant for their growth, survival, and transmission through hyphal colonisation of the host’s seed [11]. These endophytes exhibit a degree of host-specificity within the cool-season grasses of the Pooideae, whereby Epichloë species are naturally restricted to a host grass genus or closely related genera within a grass tribe [12][13][14]. Asexual Epichloë spend their entire life cycle within the plant host growing systemically within shoot tissues between plant cells [15][16][17] (Figure 2). However, their bioactivity towards certain pests in the rhizosphere [18] can be attributed to the mobility of fungal secondary metabolites in the roots, produced during the symbiosis, within the plant vascular system [15][16].

Epichloë-derived secondary metabolites protect the host plant from herbivores—both vertebrates and invertebrates. However, the effect on ruminants and several non-ruminants including horses, camels, white rhinoceros, and alpacas [19] can be detrimental and, when first discovered, removal of these endophytes from grasses was considered the best solution. However, in many temperate regions of the world, such as New Zealand, these Epichloë endophytes are essential for pasture persistence. Novel endophyte strains have now been identified and commercialised that provide the host grass with tolerance/resistance to pests, diseases, and some abiotic stresses while reducing or eliminating the debilitating animal health and welfare issues [20]. These endophytes can be transferred between plants through artificial infection [21].

References

- Hallmann, J.; Quadt-Hallmann, A.; Mahaffee, W.; Kloepper, J. Bacterial endophytes in agricultural crops. Can. J. Microbiol. 1997, 43, 895–914.

- Arnold, A.E.; Herre, E.A. Canopy cover and leaf age affect colonization by tropical fungal endophytes: Ecological pattern and process in Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae). Mycologia 2003, 95, 388–398.

- De Bary, A. Die Erscheinung der Symbiose: Vortrag Gehalten auf der Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte zu Cassel; Verlage von Karl J. Trübner: Stassburg, France, 1879.

- Schulz, B.; Guske, S.; Dammann, U. Endophyte-host interactions. II. Defining symbiosis of the endophyte-host interaction. Symbiosis 1998, 25, 213–227.

- Sinclair, J.; Cerkauskas, R. Latent infection vs. endophytic colonization by fungi. In Endophytic Fungi in Grasses and Woody Plants; Redlin, S.C., Carris, L.M., Eds.; American Phytopathological Society Press: St Paul, MN, USA, 1996; pp. 3–29.

- Saikkonen, K.; Wali, P.; Helander, M.; Faeth, S.H. Evolution of endophyte-plant symbioses. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 275–280.

- Card, S.; Johnson, L.; Teasdale, S.; Caradus, J. Deciphering endophyte behaviour: The link between endophyte biology and efficacious biological control agents. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw114.

- Leuchtmann, A.; Bacon, C.W.; Schardl, C.L.; White, J.F.J.; Tadych, M. Nomenclatural realignment of Neotyphodium species with genus Epichloë. Mycologia 2014, 106, 202–215.

- Schmidt, S.P.; Hoveland, C.S.; Clark, E.M.; Davis, N.D.; Smith, L.A.; Grimes, H.W.; Holliman, J.L. Association of an endophytic fungus with fescue toxicity in steers fed Kentucky 31 tall fescue seed or hay. J. Anim. Sci. 1982, 55, 1259–1263.

- Fletcher, L.R.; Harvey, I.C. An association of a Lolium endophyte with ryegrass staggers. N. Z. Vet. J. 1981, 29, 185–186.

- Zhang, W.; Card, S.D.; Mace, W.J.; Christensen, M.J.; McGill, C.R.; Matthew, C. Defining the pathways of symbiotic Epichloë colonization in grass embryos with confocal microscopy. Mycologia 2017, 109, 153–161.

- Schardl, C.L.; Craven, K.D.; Speakman, S.; Stromberg, A.; Lindstrom, A.; Yoshida, R. A novel test for host-symbiont codivergence indicates ancient origin of fungal endophytes in grasses. Syst. Biol. 2008, 57, 483–498.

- Saikkonen, K.; Faeth, S.H.; Helander, M.; Sullivan, T.J. Fungal endophytes: A continuum of interactions with host plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1998, 29, 319–343.

- Schardl, C.L. The epichloae, symbionts of the grass subfamily Poideae. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2010, 97, 646–665.

- Card, S.D.; Rolston, M.P.; Park, Z.; Cox, N.; Hume, D.E. Fungal endophyte detection in pasture grass seed utilising the infection layer and comparison to other detection techniques. Seed Sci. Technol. 2011, 39, 581–592.

- Christensen, M.; Voisey, C. The biology of the endophyte/grass partnership. N. Z. Grassl. Assoc. Res. Pract. Ser. 2006, 13, 123–133.

- Christensen, M.J.; Bennett, R.J.; Ansari, H.A.; Koga, H.; Johnson, R.D.; Bryan, G.T.; Simpson, W.R.; Koolaard, J.P.; Nickless, E.M.; Voisey, C.R. Epichloë endophytes grow by intercalary hyphal extension in elongating grass leaves. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008, 45, 84–93.

- Popay, A.J.; Bonos, S.A. Biotic Responses in Endophytic Grasses. In Neotyphodium in Cool-Season Grasses; Roberts, C.A., West, C.P., Spiers, D.E., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Ames, IA, USA, 2005; pp. 163–185.

- Hume, D.E.; Ryan, G.D.; Gibert, A.; Helander, M.; Mirlohi, A.; Sabzalian, M.R. Epichloë fungal endophytes for grassland ecosystems. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 233–305.

- Johnson, L.J.; De Bonth, A.C.M.; Briggs, L.R.; Caradus, J.R.; Finch, S.C.; Fleetwood, D.J.; Fletcher, L.R.; Hume, D.E.; Johnson, R.D.; Popay, A.J.; et al. The exploitation of epichloae endophytes for agricultural benefit. Fungal Divers. 2013, 60, 171–188.

- Latch, G.C.M.; Christensen, M.J. Artificial infection of grasses with endophytes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1985, 107, 17–24.