While the concept of “evolutionary conservation” has enabled biologists to explain many ancestral features and traits, it has also frequently been misused to evaluate the degree of changes from a common ancestor, or “derivedness”. From a methodological aspect, “conservation” mainly considers genes or traits which species have in common, while “derivedness” additionally covers those that are not commonly shared, such as novel or lost traits and genes to evaluate changes from the time of divergence from a common ancestor. Due to these differences, while conservation-oriented methods are effective in identifying ancestral features, they may be prone to underestimating the overall changes accumulated during the evolution of certain lineages.

1. Introduction

Searching for shared features, or conserved features, among different species allows biologists to estimate a variety of ancestral features of organisms, including possible phenotypes of common ancestors, such as Urbilateria

[1], their signaling pathways

[2] and biomolecules

[3][4]. However, when it comes to evaluating more evolved, or highly derived features or organisms, focusing only on the conserved nature may cause various inconsistencies and confusion among studies. To be specific, when trying to determine which species has phenotypically more derived features than others, comparing only conserved or commonly shared traits may underestimate how much phenotypic change has occurred since their common ancestors. This is because novel traits or lost traits are often overlooked or even ignored. For example, the pentameral symmetric body plan evolved in echinoderms is a novel trait which should not be excluded when evaluating how much the phenotypes of these species have changed since their common ancestor with other bilaterians.

This also applies to molecular-level studies. With recent increasing interest in using genome-scale omics data to study phenotypic evolution, such as the evolution of embryonic phenotypes

[5][6][7][8][9][10][11], novel traits

[12][13][14][15][16][17], loss of anatomical features

[18][19][20], and adaptive or convergent evolution

[21][22][23][24], the ambiguous use of conservation and derivedness could cause significant inconsistencies. For instance, comparisons of 1:1 orthologs tend to consider commonly shared genes among species of interest; this can be regarded as a conservation-oriented analysis. With this approach, genes that were gained or lost during evolution are often excluded. In other words, evolutionary changes achieved by genes other than 1:1 orthologs might be overlooked by these 1:1 ortholog comparisons, leading to underevaluations of how much the phenotype or the organism has derived since the common ancestor.

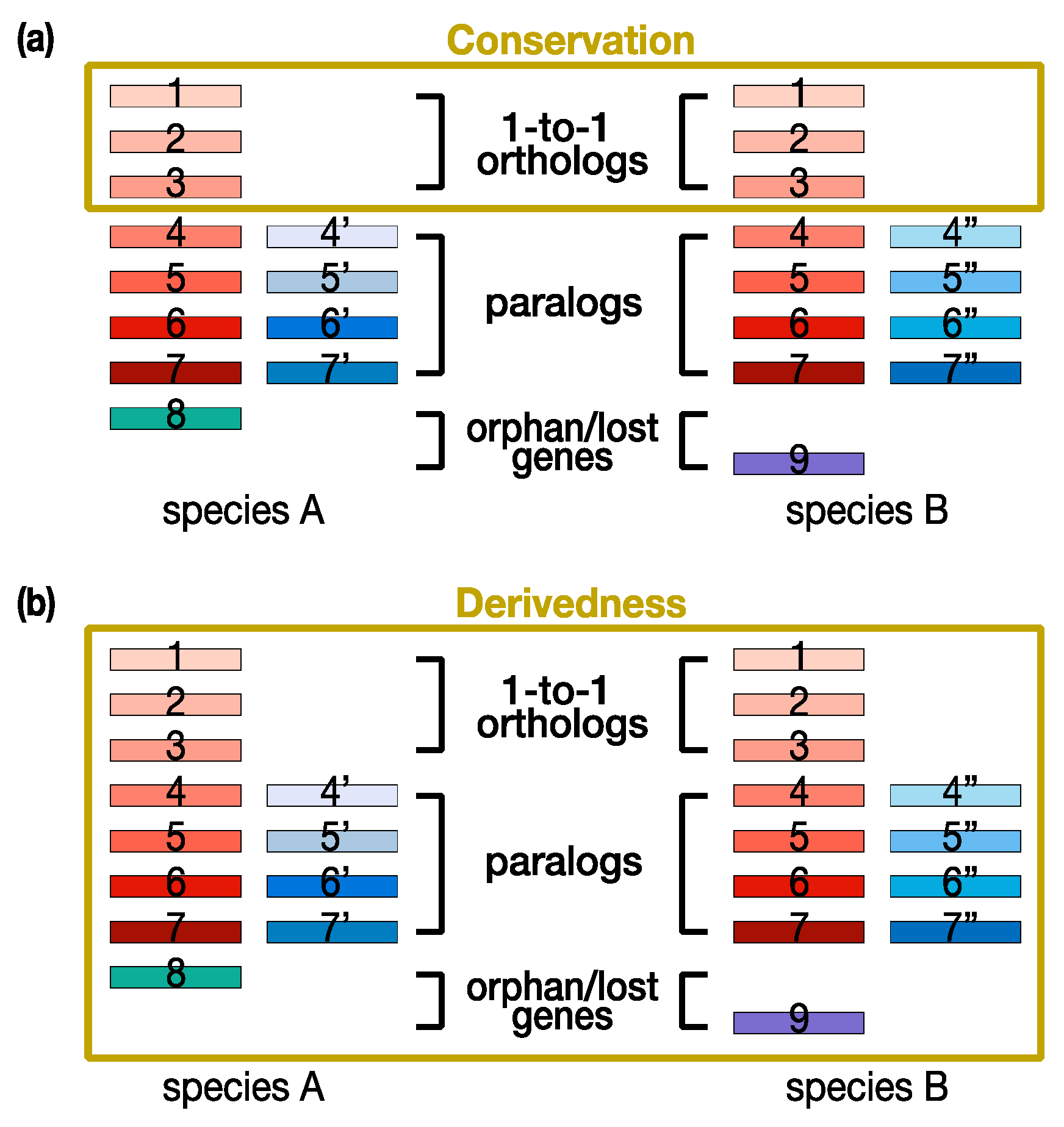

In essence, the concept of conservation, as it has often been used in previous studies

[5][11][12][25], represents information (including phenotypes and genotypes) retained during evolution. For this purpose, conservation-oriented methods tend to compare commonly shared or homologous genes and traits among the species being compared (

Figure 1a). These conservation-oriented methods have been especially powerful in explaining ancestral features and species. In contrast, the concept of derivedness represents changes that have accumulated in organisms during evolution, and thus, derivedness-oriented methods tend to cover not only conserved traits and genes, but also those that were newly acquired or lost since the split from the common ancestor (

Figure 1b). Because of these essential differences, it also should be noted that a less conserved feature is not always equal to a more derived one. This also applies to the relationship between being highly conserved and less derived. A possible scenario would be that if a certain organism has lost a tremendous number of traits (or genes) during its evolution, it is possible that it would be identified as an organism with highly conserved traits (or gene expression levels) by only comparing the commonly shared traits (or 1:1 orthologs). However, in this case, evolutionary changes by the loss of traits (or genes) would be overlooked, and so when such loss of traits (or genes) is also considered, it is more reasonable to consider the organism as highly derived rather than less derived.

Figure 1. Conservation-oriented versus derivedness-oriented gene comparisons. (

a) Conservation-oriented methods tend to compare commonly shared genes (e.g., 1:1 orthologs). (

b) Derivedness-oriented methods additionally cover evolutionary changes of nonshared genes, such as 1-to-many orthologs, paralogs, and species-specific acquired or potentially lost genes. Rectangles: genes. Red: homologous genes inherited from the common ancestor of species A and B

[26]. Blue: genes duplicated after the speciation event leading to species A and B (additionally marked by ’ and ” signs). Green and purple: orphan genes (genes without recognizable homologs in the other species).

2. Technical Limitations of Current Conservation-Oriented and Derivedness-Oriented Molecular Approaches

Although both conservation-oriented and derivedness-oriented approaches have different strengths in understanding evolution, each approach has various limitations, and thus methodology should be carefully selected depending on the purpose of research.

The conservation-oriented molecular comparisons tend to rely on commonly shared genes (e.g., 1:1 orthologs), and this approach has a limitation when a large number of species are analyzed. To be specific, due to the strict definition of 1:1 orthologs, these genes often cover only a small part of the entire gene repertoire in the genome, especially when a large number of species are compared. For example, comparing 13 species of chordates and echinoderms

[27], the researchers identified only 271 1:1 orthologous genes, which covered only ~1.5% of all the genes in a typical deuterostome genome (~20,000 genes). While these 1:1 orthologs would still be sufficient for reconstructing phylogeny

[28] or estimating the evolutionary rate of each species, their analysis may not be sufficient for evaluating derived features, or changes that accumulated during evolution, as it ignores changes that took place in the remaining ~98.5% of the gene repertoire. Even when a more sophisticated search method was employed, only 1126 1:1 orthologs were found in 18 metazoan species

[29]. As a result, the evolutionary changes within more than 90% of the genes will be excluded. Thus, the conservation-oriented molecular approach may significantly underestimate evolutionary changes, especially when derivedness is in focus. Consequently, the conservation-oriented approach may be less sufficient to elucidate the complete molecular mechanism of how derived phenotypic traits emerged or evolved. One good example would be a study done by Gildor and colleagues

[11]. To understand how changes in developmental gene expressions alter morphogenesis of echinoderm species, they analyzed the gene expression profiles of 8735 1:1 orthologs among three echinoderm species (a sea star and two sea urchins), and these 1:1 orthologs correspond to only around half of the entire gene repertoire of each species. This conservation-oriented approach was sufficient to identify conserved developmental stages (such as the gastrula stage) among the three echinoderm species. However, as the authors argued, they pointed out that their analysis might have underestimated the differences of expressions of nonshared genes (such as genes that are important for skeletogenesis in sea urchins but are absent from the sea star genome). And they also argued that these overlooked genes might contribute to species-specific, or at least sea urchin-specific, morphological features. A similar discussion was made in the study trying to elucidate the evolution of an elaborated structure called the “helmet” in treehoppers. By comparing the transcriptomic profiles of 1:1 orthologs between treehoppers and leafhoppers (their sister group which retains an ancestral condition in the dorsal wall), Fisher and colleagues

[15] found that the elaborated helmet may have evolved through coopting the wing-patterning network from the common ancestor of treehoppers and leafhoppers. Using this conservation-oriented approach, many commonly shared genes in the wing-patterning network could be identified as being expressed in the elaborated helmet, supporting the co-option hypothesis. However, this has yet to explain why the coopted gene expressions could transform the dorsal wall into a much more elaborated helmet morphology in treehoppers. Further studies are awaited to fully elucidate the molecular mechanism, and it is tempting to know if derivedness-oriented approach encompassing the nonshared genes would yield additional insights. As in the other studies, 7635 1:1 orthologs could be identified from the de novo assembled transcriptomes of the two species, which only corresponds to approximately half of the entire gene repertoire.

In contrast to the conservation-oriented approach, evolutionary changes achieved by duplicated, newly acquired and lost genes could play significant roles in phenotypic evolution because they are often considered as important drivers of phenotypic innovations

[30][31][32]. However, despite the possibility to include these nonshared genes into comparison, current derivedness-oriented approaches also have a major limitation. There is still no widely accepted way to compare the attributes (such as expression levels) of paralogs, newly acquired genes, species-specific orphan genes, and potentially lost genes across species, although several trials have attempted to compare them using an ortholog-group approach

[7][33]. In Levin et al.

[33], the expression level of an ortholog-group was determined by the expression level of the gene with the largest expression fold change, although they found no significant difference when randomly selecting a paralogous gene as the representative expression level of the ortholog-group. Similarly, in Hu et al.

[7], the authors found essentially the same results (i.e., persistent conservation of the mid-embryonic body plan-developing phase in vertebrates) by taking either the mean or the sum expression level of all predicted paralogous genes to define the expression level of an ortholog-group. These approaches are mostly based on the assumption that the functions of the putative ancestral gene became distributed among paralogs while neofunctionalization could occur, and yet further research is needed to assess to what extent these estimation methods are appropriate, or whether more sophisticated models of transcriptome evolution should be incorporated into the estimation (such as insights from studies that aimed to investigate the evolution of gene expressions involving duplicated genes

[34][35]).

A possible exception is that when two organisms being compared have the exact same pairs of orthologs, comparison of 1:1 orthologs could be regarded as both conservation-oriented and derivedness-oriented method. Hence, methodologies are not always linked with either conservation-oriented or derivedness-oriented, and analytical methods and data should be designed to fit the purpose of research.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/life12030440