Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

In Romania, wine production has traditions from the time of the Dacians and the Romans, and Romania has occupied positions in the first part of the ranking of European, respective world wine producers. At the other pole, Romanian tourism, but especially tourism in rural areas of Romania, has experienced a significant development in the past decades, and its link with wine tourism could lead to a sustained development of rural communities in areas with wine-growing concerns, to increase their reputation and as a result, to direct new flows of tourists to these areas.

- Romania

- wine tourism

- Old World

- consumer profile

- rural tourism

- COVID-19

1. Introduction

Wine, whose existence has been known since antiquity—closely linked to the deities—played an important role in Eastern religions; it continues to be found in the current religious service of the Christian world. Starting from its status as “liquor of the gods”, wine has made its way into human existence and accompanies people from birth to the end of life—in moments of joy, sorrow, or melancholic/nostalgic moments. However, above all, wine is considered a food and, equally, a medicine [1].

Nowadays, wine has become an important beverage that is increasingly being consumed more frequently all over the world, and its production and marketing has received increasing attention from consumers, specialists, and producers [2][3][4][5][6][7][8]. As a result, the growing importance of wine tourism for many destinations and the role of this type of tourism in supporting local economies is now beginning to be understood [2][9][10]. It has also been highlighted that wine tourism can play a significant role in the development of tourism by contributing to the economic and social support of local regions and communities [11]. Wine is one of the ingredients of journeys, and journeys dedicated to wine-producing areas have led to the tourism product known as wine tourism.

2. Current Insights

In terms of the results obtained and previous studies from the literature review that have been presented [12][13][14][15][16][17][18], it can be concluded that the wine tourist is very different from country to country. In this case, it is quite difficult to draw a profile of the wine tourist from the Old World. This result can be explained by the cultural differences, levels of economic development, tourism development, and wine tourism history.

By age, the researchers can include the Romanian typical wine tourist in Generation Y or Millennials. Several studies were carried out to find their preferences regarding wine consumption. Wine Market Council Report for the USA in 2017 revealed that 26% of millennials are high-frequency wine drinkers compared to 42% of baby boomers [19]. For Romania, Chivu-Draghia and Antoce [20] showed that Romanian millennials drink less wine than Generation X consumers. Similar results were obtained for Australia [21].

The results indicate that the typical Romanian wine tourists prefer medium-sweet red Romanian wine. This result partially invalidates H1 (Romanian WT consumers drink dry red wine). The differences between red/rose and off-dry/medium sweet are 1.8 and 2.5 points. The results represent the preference of the Romanian wine tourist and not of the Romanian wine consumer.

Worldwide, rose wine production has a growth rate of 18% and has been on a positive trend since 2002 [22]. Rose wine is a trend, for large retail outlets, identified by the International Organization of Vine and Wine in 2015 [23]. The most important markets for rose wine are France, USA, and Italy [24].

In USA, dry red wine is preferred by all generations [25]. Several studies on Millennials preferences revealed different results: Australian Millennials drink mostly white wine [21], New Zealand Millennials prefer red wine [26], Australian Millennials are more likely to prefer white wines and change to red wine as they age [27], and Romanian Millennials prefer medium-sweet white wine [20].

Completing the profile of the Romanian wine tourist the researchers can add more information from the research. On average, he had visited a winery in a group of friends, had 2.4 visits in the last 2 years, and was willing to spend an average of RON 75 (EUR 15) for a four-wine tasting accompanied with a plate of cheese and fruits. He has higher education and an above average income. The main reasons for visiting a cellar were tour and wine tasting and buying wine from the winery.

In general, Romanian wine tourists have a favorable perception and understand the connection between wine tourism and rural tourism. As mentioned earlier, people who know better what wine tourism means have almost twice as favorable an opinion about the positive contribution to the development of rural tourism (validates H2). The general opinion about the positive contribution of wine tourism to rural tourism and local community is in line with other international studies [28][29][30][31][32][33][34].

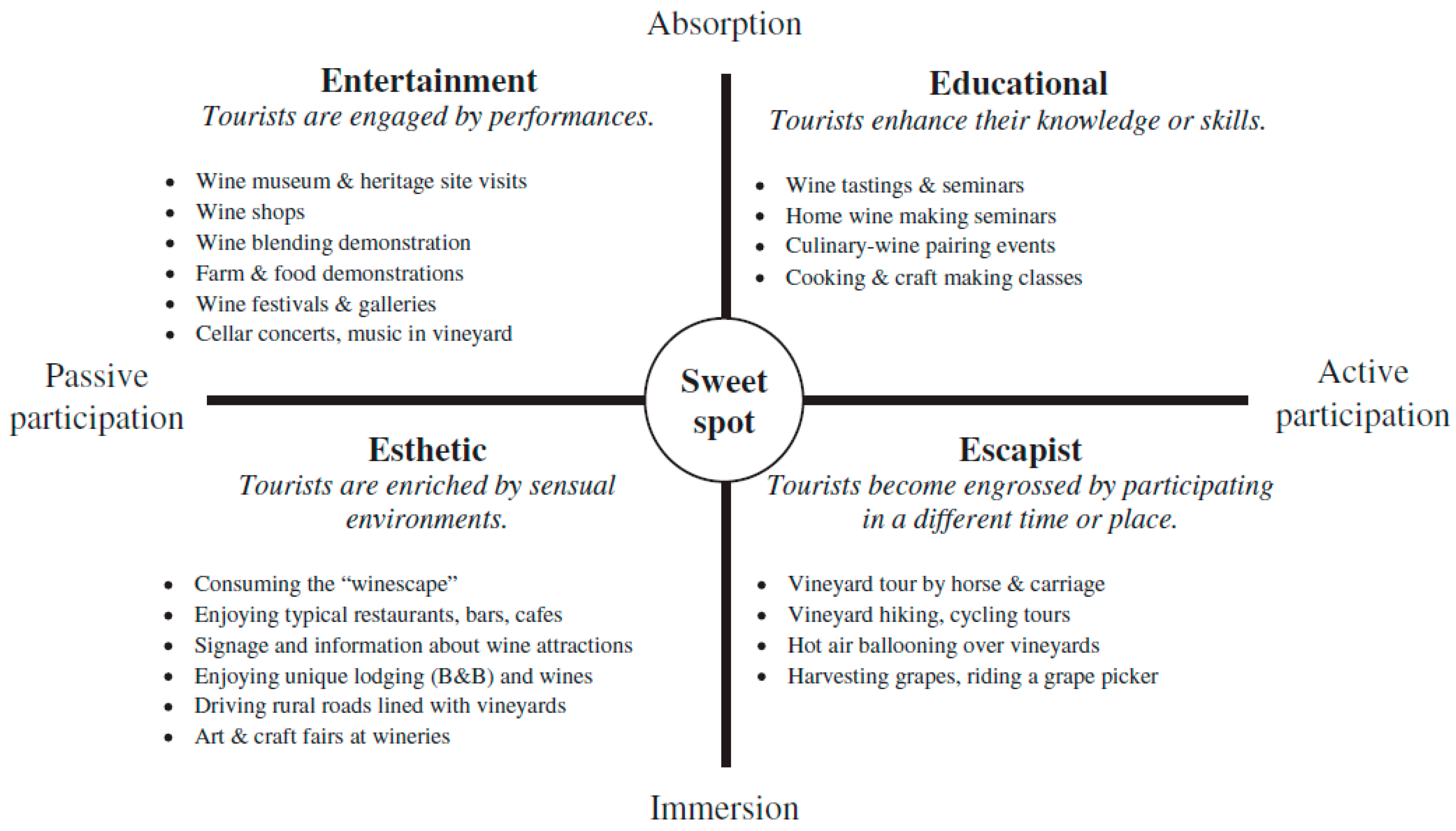

However, more experienced Romanian wine tourists (with more visits) show a divergent opinion. A high number of visits leads to a decrease in confidence that rural tourism can be developed through wine tourism. They notice a rupture in the relationship between the winery and the local community. Tourists who are more experienced could compare Romanian wineries’ offer with other international experiences. In many cases, most of the activities that can be performed at Romanian wineries are: tour, wine tasting, buying wine, renting bikes, serving lunch, and sometimes accommodation. With an adaptation from Quadri-Felitti and Fiore [35], Thanh and Kirova [36] suggested a range of activities grouped in four categories created from two categories of opposing items: absorption/immersion and active/passive participation (Figure 1). The results revealed a prominence of only two activities: tour and wine tasting, and wine purchase. Close to this one, from the frequencies obtained is another activity—visiting the winery. The other items introduced in the research and connected to other types of activities: accommodation, and rest and relaxation, which can be achieved by passive participation and active participation in typical vineyard activities. The latter are less mentioned in the responses. Romanian wineries do not offer opportunities to spend free time in the surroundings or based on local resources. More experienced tourists notice this—poor diversification of tourism services with a negative impact on the perception of the contribution of wine tourism to the development of rural tourism. Based on their opinion, the researchers can say that H3 is confirmed.

As have been shown in the literature review and in Figure 1, there are many activities that can be performed based on local resources. All these activities strengthen the link between wine tourism, rural areas, and communities. The researchers also need to consider that wine tourism in Romania is at the beginning and, for now, the vineyards are offering only the basics. The number of tourists is not necessarily high and seasonality is very pronounced with peaks in some summer and fall weekends. Slowly, the vineyards are developing other services as the researchers have seen from the frequencies obtained. For now, this is the exception and not the general rule in conducting wine tourism at a local level.

Without a close relationship, there are no premises for a substantial contribution of wine tourism to the development of rural tourism. This must be based on the participation of wineries in community life and not just in economic terms. Connecting the entire range of tourism resources can improve the perceived quality of the wine tourism experience and connect more closely the wineries with local communities. In this way, wine tourism can really contribute to rural development.

By identifying the main activities that Romanian wine tourism has carried out at the winery, the researchers can add two more characteristics to his profile. He is interested in the educational aspects (wine tasting) and entertainment (visits and wine shops). The escapist and esthetic activities are almost non-existing in the Romanian wine cellars. This fact strengthens the importance of the research for the future development of activities based on local resources. The practical implications for the business environment are multifaceted.

They can attract other types of tourists by developing activities on the Immersion side. The two areas that address active (escapist) or passive (esthetic) participation present a considerable opportunity to grow with multiple benefits for vineyards, other businesses in the area and local community. In connection with those from entertainment and educational that link local resources (farm and food demonstration, culinary wine pairing events, and cooking and craft classes) vineyards have the opportunity to develop a unique product with long-term wide spread benefits. Developing more elaborate activities, vineyards may involve local artisans (art and craft, music, and folklore) and other small businesses (farm producers, local guides, and other touristic services). In this way, vineyards can contribute to the sustainable development of rural areas and tourism. On the other hand, they will ensure their long-term sustainable development by establishing a well-known wine tourism offer.

In this way, the local community can participate in the offer of the wine cellar, and the wine cellars will become a part of the local community. Wine tourism can follow the right path and increase its contribution to the development of rural tourism. Being at the beginning, the road will be bumpy, but the researchers are confident that the national WT offer will develop and catch-up to countries with a tradition in this type of tourism.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14074026

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!