Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Neurosciences

The cranio-orbito-zygomatic (COZ) approach is an extension of the pterional approach, involving the adjunct of orbitozygomatic (OZ) osteotomy to allow wider exposure of the anterior and middle skull base and upper retroclival region. It provides advantages in giant aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) and distal basilar artery, tuberculum sellae, large anterior clinoidal, spheno-orbital meningiomas, large craniopharyngiomas, giant pituitary adenomas, cavernous hemangiomas of the hypothalamus, and crus cerebri of the midbrain.

- carotid-oculomotor window

- optic-carotid window

- orbitozygomatic approach

- orbitopterional approach

- pterional craniotomy

- skull base approach

- surgical anatomy

1. Introduction

The cranio-orbito-zygomatic (COZ) approach is an extension of the pterional approach, involving the adjunct of orbitozygomatic (OZ) osteotomy to allow wider exposure of the anterior and middle skull base and upper retroclival region. It provides advantages in giant aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) and distal basilar artery, tuberculum sellae, large anterior clinoidal, spheno-orbital meningiomas, large craniopharyngiomas, giant pituitary adenomas, cavernous hemangiomas of the hypothalamus, and crus cerebri of the midbrain. Over the years, a wide range of terms has been used to describe this approach, each of which refers to the key steps of the bony work of a specific variant. Similarly, many technical notes of the COZ approach have been reported to make its execution easier and decrease the risk of complications [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. All these aspects have inherently been sources of confusion, thus risking excessively emphasizing the technique of execution rather than the impact that removal of the OZ complex has in increasing the angle of view of the subfrontal and subtemporal anterolateral perspectives, especially when completed with anterior and posterior clinoidectomy.

The herein presented PRISMA-based literature review strives to exhaustively summarize the spectrum of possible technical variations of the COZ approach, particularly focusing on the different quantitative effects resulting from removal of the entire OZ bar, orbital rim, and zygomatic arch. The reported data constitute the key elements for rational tailoring of the COZ approach aimed at optimizing the volume of exposure of the target, augmenting surgical freedom, and decreasing the risk of complications.

2. Core Techniques for Tailoring of The Cranio-Orbito-Zygomatic Approach

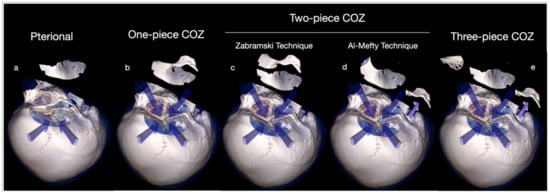

The present review summarizes the key techniques for tailoring the amount of surgical exposure provided by the COZ approach, which is today considered a workhorse of skull base surgery. A gradual shift from the one-piece technique to the two-piece or three-piece technique occurred over the years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison between pterional approach (a) and one-piece (b), two-piece (c,d), and three-piece (e) COZ approach.

The reasons consist of easier execution of the latter two variants, as well as better functional and cosmetic outcome [6,11,29,30]. Some authors also stress the safer profile of the three-piece technique deriving from the fact that the cuts of the orbital roof are performed by the intracranial side under direct vision [14]. A series of in-depth anatomical quantitative studies have clarified the effects of OZ osteotomy [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. It has three main advantages, namely (1) a wider working room allowing handling the lesion from different angles of view, (2) a shorter working distance for deep neurovascular targets, and (3) an increased subfrontal and subtemporal angular exposure. These points considerably reduce the need for brain retraction, at the same time expanding tremendously the limits of the pterional route, as reported by our group [41] Among the transcranial anterolateral approaches, the COZ holds maximum surgical freedom toward a high number of deep targets because it allows concurrently combining the subfrontal, transsylvian, pretemporal, and subtemporal routes. Wide splitting of the Sylvian fissure is the key for all these corridors, which can be used in combination especially in giant or complex aneurysms as stressed by our group [15,41,42,43,44,45]. Comparing the pterional and COZ approach in terms of angular exposure and surgical freedom, Alaywan and Sindou demonstrated that removal of the OZ bar in a single block is responsible for an increase of 8°, 6°, and 10°, respectively, on the plane sagittal, coronal, and axial [36]. This additional exposure is valid for almost all lesions for which the COZ approach has indication. Angular exposure of the ACoA complex, basilar bifurcation, and posterior clinoid is increased by 75%, 46%, and 86% on average in the subfrontal, pterional, and subtemporal approaches, respectively [36]. Schwartz and colleagues reported that exposure caused by additional removal of the OZ bar is as long as the distance between the sphenoid wing and the highest point of the target on the sagittal and coronal plane (Table 1) [32].

Table 1. Average Area of exposure of different targets according to Schwartz et al. [32].

| Approach | Area of Exposure (mm2 ± SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior Clinoid | Tentorial Edge | Basilar Tip | |

| Pterional | 2915 ± 585 | 2521 ± 301 | 1639 ± 244 |

| Orbitopterional | 3702 ± 943 | 3536 ± 539 | 2020 ± 350 |

| COZ | 4170 ± 1053 | 4249 ± 1186 | 2400 ± 386 |

In particular, for the basilar apex and posterior clinoid, the removal of the orbital rim and zygomatic arch as separate steps results in an increase of exposure of 28% and 22%, respectively (Table 2) [32].

Table 2. Percentage increase in exposure of different targets according to Schwartz et al. [32].

| Approach | Surgical Target (% Increase in Exposure) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior Clinoid | Tentorial Edge | Basilar Tip | |

| Orbitopterional | 26 * | 39 * | 28 * |

| Pterional + Zygomatic Osteotomy | 13 | 17 | 22 |

| COZ | 43 * | 64 * | 51 * |

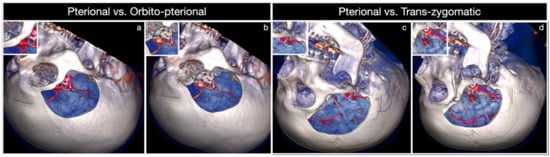

Based on these data, the COZ approach can be tailored depending on the location and size of the lesion, as well as the specific corridor deemed more suitable for the target exposure [41,46]. Many authors support OZ osteotomy exclusively for lesions projecting upward, such as high-riding ACoA and basilar tip aneurysms or intra-axial tumors abutting within the basal forebrain of the interpeduncular fossa. However, it has been proved that the increase in surgical freedom of OZ osteotomy concurs to significantly enhance the working space also for lesions extending downward [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Among the latter, a robust example is given by basilar apex aneurysms involving low-riding basilar bifurcation, as in Case 1 or voluminous parasellar tumors, especially if extended to the infratemporal fossa. The subfrontal and transsylvian perspectives are used to clip large and giant ACoA aneurysms, whereas the four deep windows related to the transsylvian and pretemporal corridors, along with the subtemporal corridor, are the main access routes to basilar tip aneurysms and ventral midbrain lesions lying in the crural and ambient cisterns [47,48,49,50,51,52]. In the COZ approach, additional exposure resulting from the OZ osteotomy is to be considered as spherical around the target rather than linear upward or downward, thus allowing for a multiangled approach to the lesion. Increasing surgical freedom related to the COZ approach in comparison with the pterional transsylvian approach is based on this key concept [41]. As specifically concerns the increase in angular exposure, superolateral orbitotomy has been reported to have quantitative and qualitative effects extremely different from those of zygomatic osteotomy [3,22,31,32,35,36,37,38,39,40,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Removal of the orbital rim, which should be considered the roof of the subfrontal perspective, significantly raises the roof of the subfrontal corridor increasing the obliquity of the line of sight backward and upward. This key step constitutes an advantage in terms of surgical freedom to the basal forebrain [8,32,37,40,53]. It also enhances the anterolateral perspective to the anterior cranial fossa through the transsylvian route (Figure 10a,b). Conversely, while not affecting the exposure of targets such as posterior clinoid, tentorial edge, and basilar apex, zygomatic osteotomy adds advantages to the pretemporal and subtemporal corridors through additional illumination of the blind spots in the depth and shortening of the working distance to the interpeduncular cistern (Figure 2c,d) [32,54].

Figure 2. Comparison of the surgical exposure between the pterional (a) vs. orbitopterional (b) approach and the pterional (c) vs. trans-zygomatic (d) approach.

While subtraction of the orbital rim is useful for high-riding aneurysms of the basilar apex, the shallower operative field resulting from zygomatic osteotomy enhances the pretemporal, subtemporal transtentorial, and subtemporal transpetrosal (Kawase’s) approaches in cases where the basilar tip aneurysm originates at the level of low-riding basilar bifurcation [61]. An anatomically shorter ICA narrows the optic-carotid and carotid-oculomotor window but enhances the supracarotid corridor to the interpeduncular region. Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that accessibility of the supracarotid window can be severely limited in the case of obstruction by part of the perforating arteries originating from the ICA apex. Anterior clinoidectomy, opening of the distal dural ring of the ICA, ICA mobilization, and optic foraminotomy further expand the versatility of the COZ approach for what concerns the paraclinoid region and infratentorial targets [62,63]. Lateral mobilization of the ICA can be useful to further expand the optic-carotid corridor in giant aneurysms of the basilar tip or high-riding basilar bifurcation patterns, the latter having an incidence of 30% [64,65,66,67]. On the contrary, medial mobilization of the ICA, posterior clinoidectomy, and splitting of the tentorium significantly increase the length of proximal exposure of the basilar trunk in cases where the basilar bifurcation is very low riding. This bifurcation pattern characterizes about 20% of patients [64,65,66,67].

2.1. Complications Avoidance

Complications of the COZ approach can be functional, aesthetic, or of both types. Some of the most frequent are injury of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve, atrophy of the temporalis muscle, masticatory imbalance, enophthalmos, diplopia, visual impairment, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage. The subfascial technique avoids deficit of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve, whereas compulsive subperiosteal blunt and “cold” (avoiding electrocauterization) dissection of the deep temporal fascia prevents postoperative atrophy of the temporalis muscle [20,24,27,41]. The subfascial technique has been reported to be safer than the interfascial technique because of anatomical variability of the frontotemporal ramus according to which, up to 30% of cases, some nerve twigs may be found within the two fascial layers [68]. Preservation of the normal trophism of the temporalis muscle is the result of some important aspects; Apart from the subperiosteal retrograde Oikawa dissection technique [19], caudal mobilization of the zygomatic arch has also been reported to decrease the risk of atrophy escaping compression of the muscle secondary to its reflection [20]. Avoidance of detachment of the masseter, along with functional preservation of the temporalis muscle, prevents the risk of masticatory imbalance. Incidence of diplopia, facial and orbital asymmetry is lessened by meticulous osteosynthesis, which is generally performed using low-profile miniplates and screws. Preplating aids in approximation of the bone flaps. Protection of the periorbita is of utmost importance to avoid enophthalmos and postoperative orbital hematoma. Risk of visual impairment or even blindness mainly comes from anterior clinoidectomy, which is added to COZ craniotomy in most cases. Risk of thermal damage to the optic nerve secondary to overheating caused by the high-speed drill must be decreased by constant irrigation. Excessive downward displacement of the eyeball during the approach is a further potential source of visual morbidity. The need to expand the subfrontal corridor frequently implies violation of the frontal sinus. Undesired communication with the sphenoid sinus can be the result of anterior clinoidectomy in cases where the anterior clinoid process is highly pneumatized. Meticulous packing of both these sites with a piece of muscle or autologous fat is recommended to dramatically reduce the risk of infections and cerebrospinal fluid leak. Reflected galea-pericranium vascularized flap constitutes a further barrier.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/brainsci12030405

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!