Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Irish society went into one of the most stringent lockdowns in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and barring a few weeks, remains highly restricted at time of writing. This has produced a wide range of challenges for those affected by eating disorders, as well as treatment services and Bodywhys, The Eating Disorders Association of Ireland. Current research indicates that COVID-19 has impacted across three key areas—the experience of those with an eating disorder, the experience of service provision, and the impact on the family situation.

- eating disorders

- COVID-19

- pandemic

- parents

- carers

1. Introduction

Initially, Ireland responded quickly and decisively to the COVID-19 pandemic. The first national case was confirmed on 29 February 2020. On March 11 the World Health Orgnisation (WHO) declared the Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic, and the first Irish fatality was recorded. A day later, on 12 March 2020, the Government announced the closure of schools, colleges, and childcare facilities [1]. In a public address on 17 March 2020, the Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Leo Varadkar, asked people to ‘come together as a nation by staying apart from each other’ [2]. On 24 March 2020, the Taoiseach announced stringent new measures designed to halt the spread of COVID-19, describing them as ‘unprecedented actions’ to respond to an ‘unprecedented emergency’. Currently, Ireland has been under one of the longest COVID-19 lockdowns in Europe with restrictions in place since Christmas 2020. Over the past year, restrictions have been adapted many times, leading to uncertainty both for individuals and organisations. This paper reviews how people affected by eating disorders in Ireland were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing on monitoring and evaluation data gathered by Bodywhys, the Eating Disorders Association of Ireland, which works alongside public and private treatment providers.

The Irish health system is divided into the public service available to all and the private service available to those with private health insurance. The public health service is provided by the Health Service Executive (HSE). Within the HSE’s mental health section, there are services provided at different levels according to assessed risk. Primary care, community mental health teams, day patient and inpatient services. Specifically, for the treatment of people with eating disorders, in the main, treatment is provided in the community, by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Team (CAMHS) or the Adult Mental Health Team (AMHS). To address eating disorders specifically, the HSE developed a National Clinical Programme for Eating Disorders (NCP-ED), launching the NCP-ED’s Model of Care in 2018 [3]. This is essentially a blueprint for the provision of skilled, experienced and specialist eating disorder teams nationally. No matter where the person is located, they will have access to a specialist team for their treatment. Importantly, Bodywhys was included on the working group for the development of NCP-ED and is identified as the partner to support the implementation of NCP-ED.

Impact of COVID-19 on People Affected by Eating Disorders in Ireland

There was a 66% increase in hospital admissions for eating disorders amongst children and adolescents in Ireland since the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to 2019 [4] and paediatric hospitals and acute hospitals have also reported increased acute presentations [5][6]. In Crumlin’s Children Hospital, Dublin, both community and hospital presentations for eating disorders increased during 2020, by three to four times, compared to 2019 [7]. Staff in Crumlin indicated that more acute presentations were evident, along with increases reported by their colleagues in Temple Street Hospital, Tallaght University Hospital and CAMHS. The HSE’s Child and Adolescent Regional Eating Disorder Service, CAREDS, for the Cork/Kerry region, reported two to three times the amount of young people needing help since the pandemic began [8]. In most of these examples, hospitalisations were underlined by the fact that people were more unwell, requiring stabilisation. Clinicians in Sligo/Leitrim Mental Health Services reported a 40% increase in eating disorder referrals amongst children and adolescents since March 2020 [9]. Increased inpatient emergency department admissions for eating disorders were reported in the Galway region [10]. In adult services, increased referrals, particularly in the 18–24 year old range, were also reported [11]. This includes people who have relapsed and those presenting with a new illness, higher instances of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa and increased referrals for males. A general practitioner (GP) working in a university student health setting, shared her experience of increased presentations for eating disorders, such as binge eating disorder and restrictive eating in an online news publication [12]. The HSE’s NCP-ED published its figures for 2020 during Eating Disorders Awareness Week (EDAW), 1–7 March 2021, noting a 60% increase in referrals received and a 43% increase in assessments completed, compared to 2019 [13]. Media reporting of the HSE’s mental health section indicates that its services expect increased eating disorder referrals to continue into 2021 [6].

Bodywhys, The Eating Disorders Association of Ireland, founded in 1995, is a national voluntary organisation with charitable status. Bodywhys was established when a group of parents, who had a child diagnosed with an eating disorder, joined together to form a support group. At that time, in Ireland, there were no specific support services for people affected by eating disorders. Primary funding for Bodywhys is provided by the HSE through a Service Level Agreement (SLA). This allows the organisation to deliver support services and expand other areas of work that benefit the public, such as prevention and education programmes, continuous professional development (CPD) training, media awareness and anti-stigma campaigns.

2. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Bodywhys Support Services

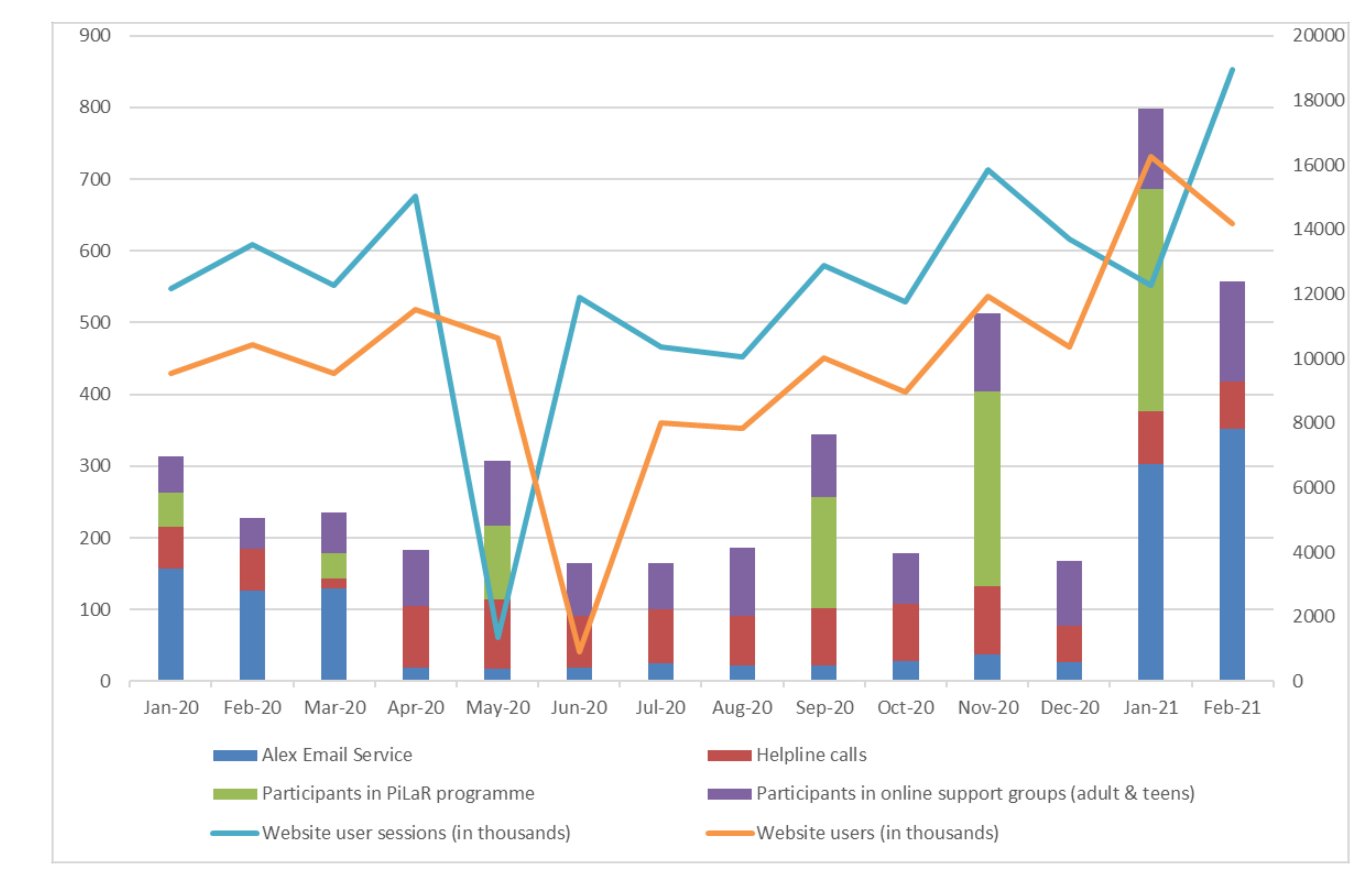

There has been an increasing demand for all Bodywhys services compared to the previous year: online support groups (111% increase, March–December 2019 vs. March–December 2020), support email contacts (45% increase, March–December 2019 vs. March–December 2020) and helpline calls (54% increase, April–December 2019 vs. April–December 2020). Figure 1 shows the participation levels across various services from January 2020 to February 2021.

Figure 1. Number of people using Bodywhys’ support services from January 2020 to February 2021. Data sourced from Salesforce and Google Analytics.

One of the most significant changes for the organisation was taking the PiLaR programme online. Typically, the programme is delivered across Ireland, face-to-face, by Bodywhys staff in a conference room, hotel, parish hall or local community setting. In January 2020, PiLaR was delivered in Cork and Wicklow. On 4 March 2020, the programme started, in person, in Dublin. Due to the pandemic, social distancing requirements, and restrictions that were implemented in Ireland, the final two weeks of this programme moved online. The remainder of PiLaR programmes for 2020—May, September and November were delivered entirely online, through Zoom. Whilst different to providing the programme in person, it quickly became evident that behind every screen there was a family supporting a person with an eating disorder. Not surprisingly, the new delivery format meant there was significant growth in attendance. In total, 683 people attended in 2020, compared to 309 who availed of the programme 2019, reflecting an increase of 121% (PiLaR monitoring and evaluation data). According to the data, PiLaR attendees are supporting people aged 9 to 48 years old (46 men, 565 women, 1 non-binary, 1 transgender; Mage = 18.32, SDage = 5.87).

A core concern for Bodywhys as an organisation is that the format of the interaction is accessible, safe and meets the participants’ expectations. Since 2019 Bodywhys has gathered data to ensure that its online technologies were easy to use. Analysis of PiLaR data indicates that 57% reported that it would not be difficult for them to find time to engage and 58% agreed that Zoom would be easy to use. A total of 61% of participants were comfortable with the level of online privacy while 57% reported that they were not concerned with being overheard while attending. However, according to the responses, 41% would have preferred the PiLaR programme delivered in a face-to-face format.

3. Impact of COVID-19 for Parents and Carers in Ireland

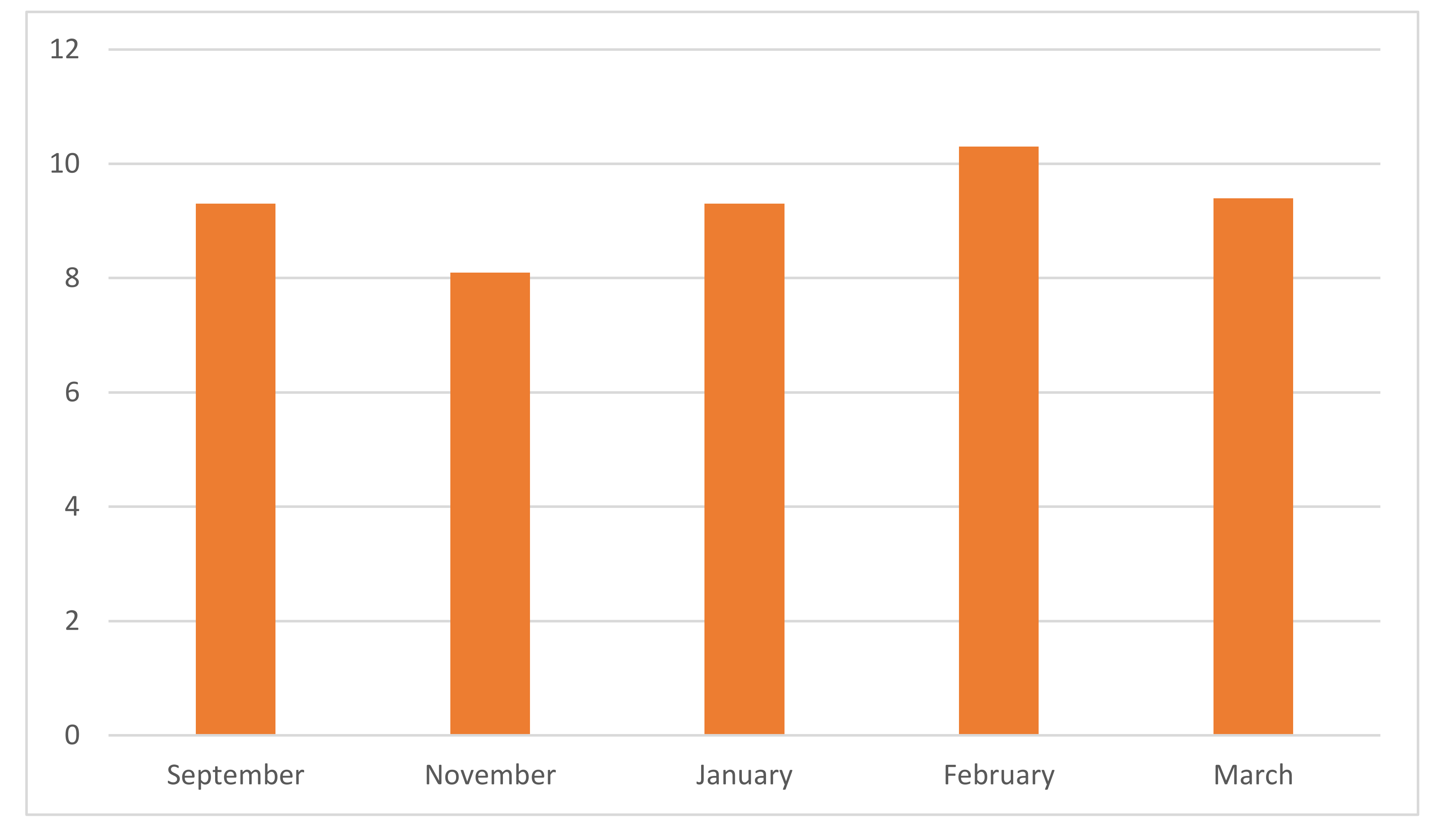

COVID-19 had a major impact on the general population, as well as those supporting people with ED in Ireland. The results from the ‘Fear of COVID-19 Scale’ (see Figure 2) indicated that there has been a consistently low level of general anxiety in relation to COVID-19. This has fluctuated to some degree (September 2020 (M = 9.3, SD = 5.2), November 2020 (M = 8.1, SD = 5.3), January 2021 (M = 9.3, SD = 5.2), February 2021 (M = 10.3, SD = 6.6), March 2021 (M = 9.4, SD = 6.5).

Figure 2. Fear of COVID-19 Scale (n = 627).

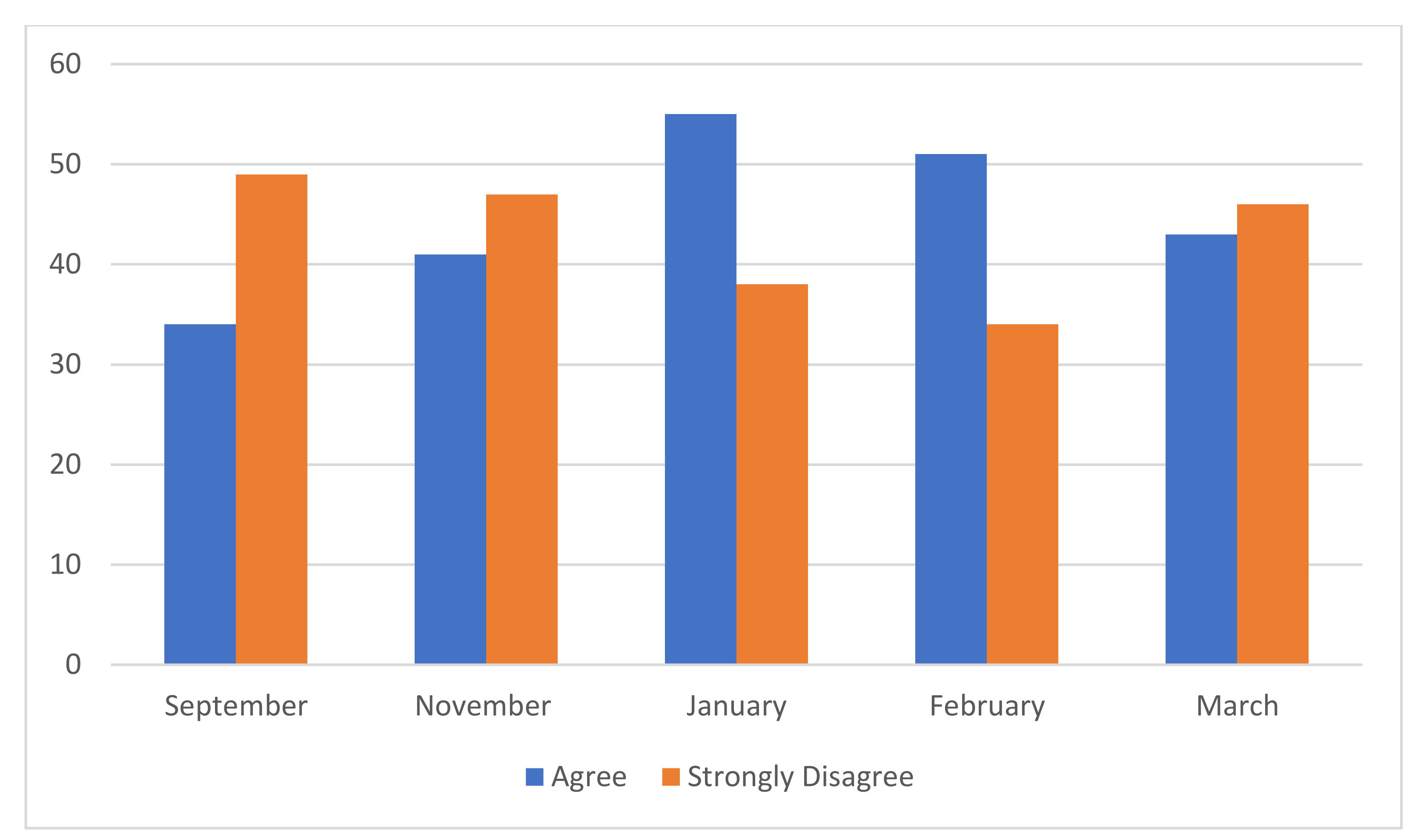

The degree to which carers felt that COVID-19 was impacting on their ability to care was also examined (see Figure 3). From September 2020, 34% of carers reported that COVID-19 was impacting their ability to provide support to the individual experiencing an eating disorder. This increased to 41% in November 2020 and 43% in January 2021. In February 2021, although there was a decrease in those who responded that they ‘agreed’ that COVID-19 was having an impact on their role as a carer, there was an increase in those who indicated that they ‘strongly agreed’ with this statement, resulting in a total of 51% of participants reporting that COVID-19 was impacting their ability to support the person with the eating disorder. This reflected the data reported in the, ‘Fear of COVID-19 Scale’ which indicated that participants experienced the highest COVID-19 related anxiety in February 2021 which consequently, may have impacted their ability to provide care for their loved ones. In March 2021, this figure decreased to 43%.

Figure 3. Impact of COVID-19 on carer’s ability to provide support: 5 rating scale to ‘COVID-19 has made it harder for me to provide support for the person with ED’. (n = 585).

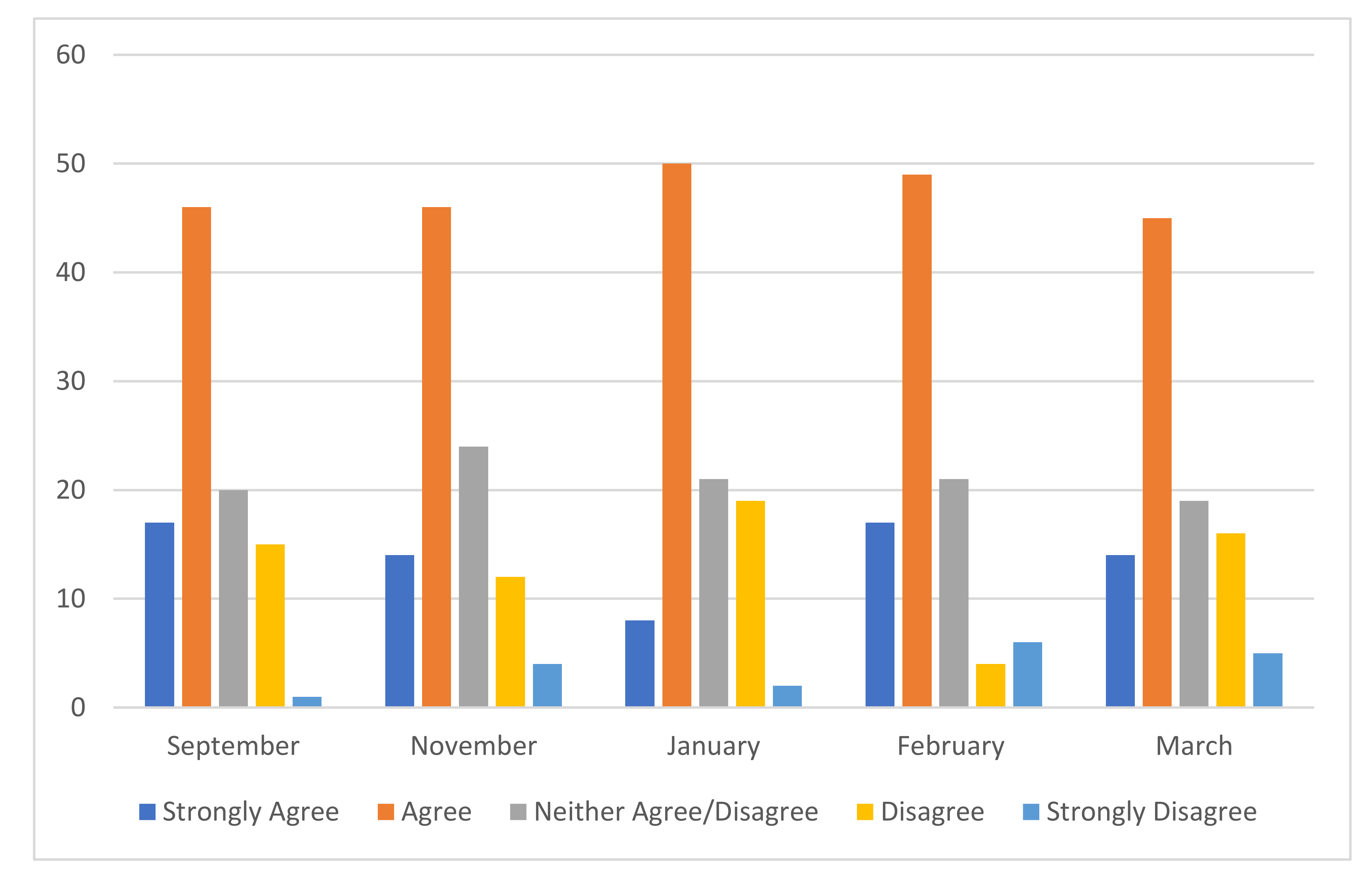

61% of the participants reported that their own mental health was being impacted by supporting someone with an eating disorder (see Figure 4). No significant change was identified in these figures over the course of seven months. See chart below.

Figure 4. Impact on Mental Health of Carer: 5 rating scale to ‘My own mental health is being impacted by caring/supporting for someone with an ED’ (n = 585).

Qualitative responses to open-ended questions in the survey also indicated that supporters were clearly felt worried about how to help:

‘I’m worried for the person in question because of COVID-19 and level 5 lockdown. And I was unsure how to help the person’.(PiLaR participant)

Alongside the difficulties that people with eating disorders were experiencing due to COVID-19, family members, friends and carers voiced the challenges of travel restrictions being in place.

‘Due to COVID-19 level 5 restrictions, I’m the only family member in the same county as my sister’.(PiLaR participant)

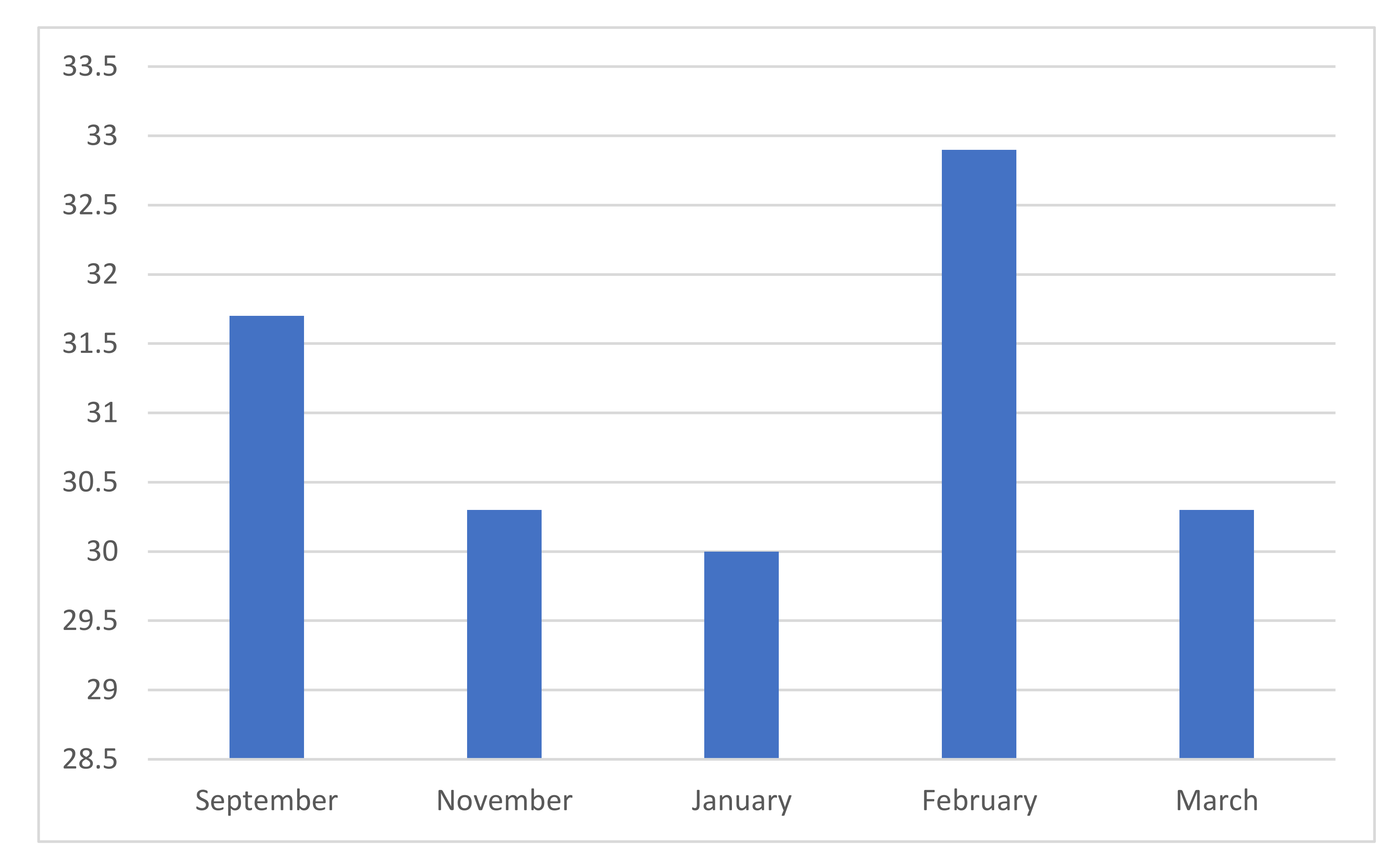

Results from the ‘Accommodation and Emerging Scale for Eating Disorders’ indicated that in February 2021 (M = 32.9, SD = 26.7), participants reported the highest figure in relation to the accommodations made by the family to support the individual experiencing an eating disorder (see Figure 5). This decreased in March 2021 (M = 30.3, SD = 23.1). According to the responses provided by the participants, the scores on the AESED were also higher in September 2020 (M = 31.7, SD = 23.1) before decreasing in November 2020 (M = 30.3, SD = 22.1) and further in January 2021 (M = 30.0, SD = 19.5).

Figure 5. Accommodation and Enabling Scale (n = 627).

These findings echo the anecdotal evidence gained from other Bodywhys services.

4. Impact of COVID-19 on People with Eating Disorders, as Reported to Bodywhys Support Services

Bodywhys does not gather routine, direct data from people experiencing eating disorders. However, insight is provided by examining the family reported data collected pre-attendance at PiLaR. The EDSIS scores suggest that the severity of eating disorder-related behaviours does fluctuate for those seeking to attend PiLaR (September 2020 (M = 32.48, SD = 19.0), November 2020 (M = 10.3, SD = 6.6), January 2021 (M = 9.3, SD = 5.2), February 2021 (M = 33.4, SD = 22.91), March 2021 (M = 29.6, SD = 16.74).

Bodywhys service users provided the organisation with anecdotal evidence of their fears and anxieties connected with all aspects of the eating disorder. People reported an intensification of eating disorder symptomatology, such as ‘eating disorder thoughts’, a reaction to the stress that had entered their lives, the sudden change to their routine, a sense of being ‘out of control’ and the threat to their recovery process. Common fears about recovery intensified. People with eating disorders mentioned fears about letting people down, about lapsing or relapsing, disappointing people, or wellness being judged by physical appearance. Many service users engaged in supports as a form of self-care, fearing relapse. Those who were doing well in recovery feared relapse due to the changed situation and stress and uncertainty that accompanied it. Many feared a reactivation of symptoms despite treatment. Evidence suggests a worsening of eating disorder symptoms and reduced coping abilities during the pandemic [14], whilst loneliness, increased interpersonal stress, balancing conflict priorities [15][16][17], household argument and fear about the safety of loved ones [18] have also been noted. A qualitative analysis of social media posts on the popular platform, Reddit, identified challenges including: disordered eating behaviours, negative body image, struggles with appetite and binge eating, loss of motivation to exercise, the stockpiling of food, anger, frustration and guilt, barriers to treatment, feeling ashamed of the associated health outcomes and a reluctance to tell others of physical distress or seek medical care [19].

In the early stages of the lockdown, fears of food shortages, shortages of ‘safe’ foods were issues, something seen as underscoring potential risk factors [20]. Anxiety from a sense of fear of being recognised, reactions to food purchases and feelings of shame when shopping has also been a worry [21]. People in contact with Bodywhys experienced an increased compulsion to engage in eating disorder behaviours, such as strict food restriction, exercise, binging and purging. The sense of being confined and an uncertainty about when the lockdown would end brought an increased sense of being out of control which in turn increased compensatory exercise behaviours, exacerbated binge eating in many cases, and increased purging behaviours. This disruption to routine and perceived control also triggered more rumination about weight, exercise and meals. Bodywhys began to hear of stress and anxiety triggering, what people called ‘emotional eating’. People reported their relationship with exercise challenging to manage. A need for secrecy about symptoms and hiding the eating disorder from others became an intense focus and fear for some. Recent literature points to emotions and disruption to routine as being amongst some the primary stressors for those affected by anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder [22]. Other challenges highlighted in this entry were exposure to triggering messaging, changes in physical activity, changes in food availability and disruption to living situation, which also impacted by those affected by other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED).

Increased time online meant increased exposure to food and exercise messaging in public discourse, increased social comparisons, thereby exacerbating eating disorder thoughts. People reported that general health messages about needing exercise for mental wellness and physical fitness made them feel anxious and ‘not good enough’. In some cases, the health messages were taken to the extreme and set as excessive goals to reach. People with eating disorders tuned into the public sentiment that this confinement would cause weight gain, the so-called ‘quarantine 15’, (15 lbs body weight), evidenced by constant media messaging. People reported finding it very difficult to tune these messages out. One of the first eating disorder papers published during the pandemic identified eating disorder specific risk factors across a number of areas; including food access, exercise difficulties, media consumption and media messaging [20]. Reports from Bodywhys service users made it clear that the pandemic exacerbated communication difficulties. Video calls, a necessary new way of connecting with others, heightened awareness of the physical self, leading to self-criticism that is potentially harmful to recovery.

Limited access to healthcare [20], disruption to treatment outcomes [18], disparity in access to eating disorder services and premature discharge from services [23] and reduced contact from clinical teams [24] have been emerged as key concerns during COVID-19. These issues, along with reliance on remote support, premature discharge, disrupted transitions into community living, treatment suspensions, limited post-diagnostic support, remaining on waiting list for treatment all presented challenges and obstacles to those with an eating disorder since March 2020. Reduced time for professionals to address changes in treatment, more self-management of the illness by people with eating disorders were experienced as challenging not just for the person with an eating disorder but also for their carers. People already in treatment experienced uncertainty about how it would progress. Telehealth, medical checks and clinicians being reassigned to other healthcare jobs were issues. For those who were undergoing inpatient treatment, restrictions were imposed, resulting in minimum physical visits with family.

Since March 2020, Irish health services have reported increased medical admissions for anorexia nervosa, and anecdotally clinicians are seeing more people presenting, far more physically unwell and in an urgent condition [4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Data from the Health Research Board (HRB) in Ireland indicates a 32% increase in adult hospital admissions for eating disoders, growing from 138 in 2019 to 182 in 2020 [25]. The 20–24 year olds were the most affected, though 18–44 year olds were significantly represented. For children and adolescents, figures increased from 54 in 2019 to 87 in 2020, a rise of 61%. This includes some repeat admissions. Reporting and media coverage has highlighted increased contact with eating disorders services has also occurred internationally. In Australia, hospital admissions have increased for anorexia nervosa, with patients requiring medical stabilisation, with factors such as anxiety and stress thought to play a role [26][27]. The Butterfly Foundation reported 150% increase in calls during the first school term compared to the same period 2019 [28]. In New Zealand, Auckland’s Starship Children’s Hospital, admissions of 10 to 15-year-olds doubled (from 33 in 2019 to 66 in 2020), along with admissions of under 20-year-olds at Auckland City Hospital [29]. A similar increase was seen across all ages at Waikato Hospital, while hospitals in Wellington saw a rise of 31%. In Canada, increased referrals have been documented in Ontario, for both inpatient and outpatient services [30][31]. In France, the Fédération Française Anorexie Boulimie (FFAB), reported a 30% increase in calls to its helpline in 2020 [32]. In the United States, the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) reported a 41% increase in messages to its telephone and online help lines in January 2021, compared with January 2020 [33]. In England, the number of children and young people seeking emergency support for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in the community reached an all-time high of 625 [34]. There were 19,562 new referrals of under-18s with eating disorders to NHS-funded secondary mental health services in 2020, a rise of 46% from the 13,421 new referrals in 2019 [35]. In London, between January and March 2021 there was a 40% increase in children receiving treatment, compared to January–March 2020 [36]. Support organisation Beat reported an increase of 173% in helpline calls between February 2020 and January 2021 [35] and a 120% increase in calls from Northern Ireland in 2020, compared to 2019 [37]. Previous research about an eating disorders helpline noted that those affected by anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were interested in counselling, whilst those affected by binge eating disorder sought emotional support [38]. Eating disorder helplines can also serve as a first step, in parallel to treatment, or as an extension of this support when in recovery and helplines may provide an outlet for carers to access information and discuss their own experiences, while supporting their family member [39]. A recent evaluation carried out on behalf of support organisation, Beat, in the United Kingdom, found that its helpline helped service users understand their eating disorder better, reduced feelings of isolation and prompted them to act, such as contacting a doctor or read more information [40].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm10153385

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!