Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

WRKY transcription factors (TFs), which make up one of the largest families of TFs in the plant kingdom, are key players in modulating gene expression relating to embryogenesis, senescence, pathogen resistance, and abiotic stress responses. However, the phylogeny and grouping of WRKY TFs and how their binding ability is affected by the flanking regions of W-box sequences remain unclear.

- AtWRKY54

- phylogenetic tree

- flanking region of W-box

1. Introduction

WRKY transcription factors (TFs) are named based on the conserved residue WRKY, which constitutes an integral part of their DNA-binding domain (DBD) and is approximately 60 residues in length. The key structural features of this domain are the conserved DNA-binding motif WRKYGQK and a zinc-finger motif at the C-terminus [1]. Previous research has indicated that WRKY TFs should be classified into three groups based on the number of WRKY domains and the type of zinc-finger motif they contain [2]. The group 1 WRKY TFs contain two WRKY domains, and each of these has a C2H2 motif. The group 2 TFs contain one WRKY domain with a C2H2 zinc-finger motif, whereas the group 3 TFs contain one WRKY domain with a C2HC zinc-finger motif. This grouping of WRKY TFs has been widely used, but molecular evidence has now shown that it is inconsistent with phylogeny [2][3][4]. For example, the WRKY genes from Arabidopsis thaliana can be grouped into group Ia, comprising AtWRKY1, -2, -3, -4, -10, -25, -26, -32, -33, -34, -44, and -58, and group Ib, comprising AtWRKY8, -12, -13, -23, -24, -28, -43, -45, -48, -56, -57, -68, -71, and -75; these two groups are sister groups. Group IIa, comprising AtWRKY6, -9, -18, -31, -36, -40, -42, -47, -60, -61, and -72, is followed [4]. However, group Ia and IIa members were treated as a monophyletic group named group IIa by Mohanta et al. [3]. In addition, some members of the groups Ia and Ib that were defined by Wang et al. [4] (AtWRKY1, -2, -3, -4, -10, -20, -25, -26, -32, -33, -34, -44, -45, and -58) were designated group I by Eulgem et al. [2]. The remaining members of Wang et al.’s groups Ia and Ib (AtWRKY8, -12, -13, -23, -24, -28, -43, -48, -56, -68, -71, and -75) were absent from the group I defined by Eulgem et al. [2]. This inconsistency among studies leads not only to improper citations of WRKY TFs, but also confuses postulations about their evolutionary scenario. The confusion may result from the fact that WRKY genes have been classified based on whether they have one or two WRKY domains. [2][3][4]. Furthermore, which type of WRKY gene is closest to the ancestral form remains unclear. Recently, it has been assumed that both types of gene (having one or two WRKY domains) evolved from one ancestral WRKY TF, following diversification and amino acid substitutions in the derived WRKY genes [5]. However, a lack of phylogenetic support makes this proposal debatable.

WRKY TFs are reported to be involved in plant growth, development, metabolism, responses to environmental stresses, and senescence [5]. For example, the WRKY TFs WRKY53, WRKY54, and WRKY70 have been characterized as leaf-senescence regulators [6][7][8]. A line of Arabidopsis thaliana overexpressing WRKY53 showed whole-plant senescence two weeks earlier than the wild type, and a knock-out line showed delayed senescence compared to the wild type [7]. In addition, the expression level of WRKY53 increased in rosette leaves prior to the expression of several senescence-associated genes (SAG), such as SAG12 [9]. These studies suggest that WRKY53 is a positive senescence regulator in the senescence process. In contrast, a loss-of-function wrky70 line showed earlier senescence than wild-type plants, suggesting that WRKY70 functions as a negative regulator of senescence [8]. WRKY54, a homologue of WRKY70, displayed similar expression patterns to WRKY70, suggesting a redundancy between these two WRKY TFs [6]. WRKY70 and WRKY54 are also crucial in the response against pathogenic infection, in that they are involved in regulating the salicylic acid and jasmonic acid signaling that is part of plant defense mechanisms [5][6][10]. Restricted lesion diameter and bacterial growth observed in wrky54wrky70 double mutants suggest that WRKY54 and WRKY70 serve as negative regulators of the leaf senescence process [6][10][11]. Therefore, WRKY53, WRKY54, and WRKY70 are regarded as three key components in the control of plant senescence and defense processes, which act by receiving external factors and conducting subsequent signaling transduction [5].

To perform their regulatory function in the modulation of gene expression, WRKY TFs bind to a consensus sequence TTGAC-C/T, named W-box, to regulate the expression of target genes [1][12][13]. An extensive survey of binding specificity showed that WRKY TFs exhibit a W-box preference [10]. According to the report, WRKY11 (a member of group IId) binds to the second and eleventh W-box of Arabidopsis thaliana senescence-induced receptor-like kinase (AtSIRK) promoter, while WRKY26 (group I) binds to the eighth W-box of promoter AtSIRK [10]. In addition, they found that WRKY11 binds to W-box with a G residue directly at the 5′ end. In contrast, WRKY26 prefers to interact with W-box with a T, C, or A residue at the same site [10]. As a determinant of the sequence-recognition profile of WRKY TFs, the flanking region of the W-box sequence exerts a profound influence on the DNA-binding preferences of structurally similar members of this highly conserved TF family.

At present, the recognition of specific W-box nucleotide sequence preferences in A. thaliana has been elucidated by studying group I (WRKY26, as per Wang et al. [4]) and group II (WRKY11, as per Wang et al. [4]), while the preferences of group III WRKY TFs remains unknown. In the present entry, the phylogenetic tree of WRKY across the plant kingdom was reconstructed and the DNA-binding characteristics of WRKY54, a representative of the group III WRKY TFs, were determined.

2. Retrieval and Identification of WRKY Transcription Factor Genes

WRKY TF gene family was identified by using 16 species from across the plant kingdom (Table 1). These included a rhodophyte, a chlorophyte, embryophytes (two), a tracheophyte, monocots (two), and dicots (eight). In total, the researchers obtained 528 WRKY TF genes. In the selected species, the researchers identified no WRKY TFs in P. umbilicalis (rhodophyte), and only two in Micromonas pusilla (chlorophyte). Large numbers of WRKY TFs were identified in the monocots (Oryza sativa: 75; Zea mays: 62) and dicots (A. thaliana: 70). Researchers only found WRKY TFs with two WRKY domains in the embryophytes. Based on multiple sequence alignment, there were significant differences in the sequence characteristics of the chlorophyte (M. pusilla) WRKY TF and those of most of the other species. Almost all of the WRKY TFs were characterized by a conserved WRKY motif (xWRKYGQK or xWRKYGEK) with a zinc-finger motif (CxCxHTC or CxCxHxH), where x denotes any amino acid. However, the WRKY TF from M. pusilla (Mpu50253) contained a conserved WRKY motif (RWRKYGQK) with only part of the zinc-finger motif (C), suggesting that three or four conserved amino acid substitutions (C → CxCxHxH or C → CxCxHTC) occurred after plants had colonized land.

Table 1. Identified WRKYs from selected species.

| Species | No. of WRKY Gene | Taxanomy |

|---|---|---|

| Porphyra umbilicalis | x | Rhodophyta |

| Micromonas pusilla | 2 | Chlorophyte |

| Physcomitrium patens | 21 | Embryophyte |

| Marchantia polymorpha | 12 | Embryophyte |

| Selaginella moellendorffii | 7 | Tracheophyte |

| Zea mays | 62 | monocot |

| Oryza sativa | 75 | monocot |

| Musa acuminata | 45 | monocot |

| Amborella trichopoda | 20 | Angiosperm |

| Aquilegia coerulea | 6 | Eudicot |

| Spinacia oleracea | 21 | Pentapetalae |

| Solanum lycopersicum | 39 | Asterids |

| Helianthus annuus | 46 | Asterids |

| Lotus japonica | 30 | Fabidae |

| Fragaria x ananassa | 54 | Rosids |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 70 | Rosids |

| Prunus persica | 35 | Rosids |

3. Phylogenetic Reconstruction for WRKY Transcription Factors

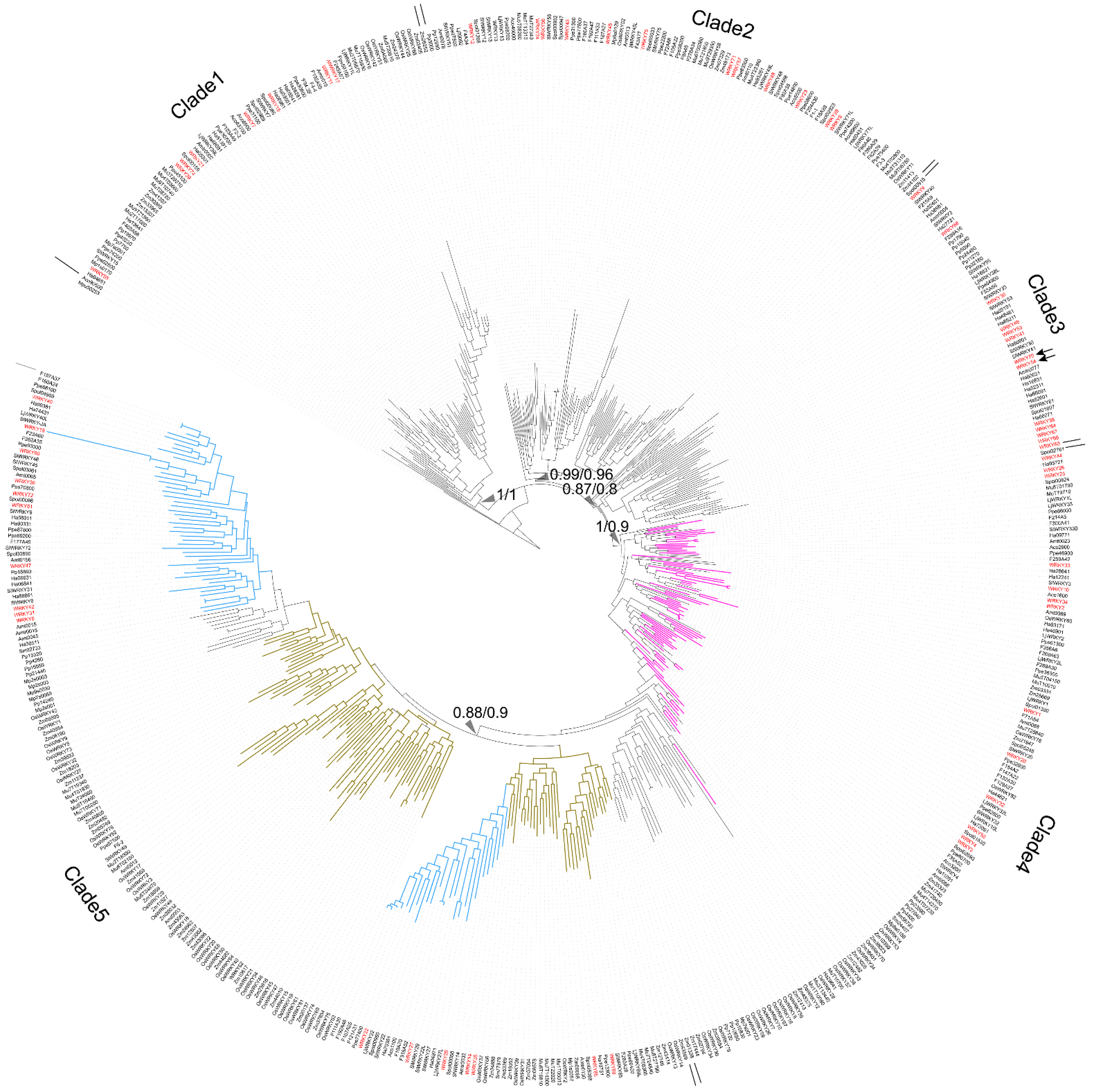

To trace the evolution of WRKY TFs, the WRKY TF obtained from M. pusilla (Mpu50253, no zinc-finger motif) was chosen as the root of the reconstructed WRKY phylogeny (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Phylogeny of WRKY transcription factors (TFs) across the plant kingdom. Red names: WRKY TFs obtained from A. thaliana. Purple branches: WRKY TFs containing two WRKY domains. Pale blue branches: the dicot WRKY TF subclade. Brown-yellow branches: the monocot WRKY TF subclade. Arrows: WRKY TFs related to the leaf-senescence process in A. thaliana, including WRKY54 and WRKY70. Triangles indicate Bayesian inference/maximum likelihood supporting statistic values respectively.

Clade 1 comprised the WRKY TFs obtained from O. sativa, A. thaliana, S. lycopersicum, P. persica, Fragaria x ananassa, M. acuminata, A. trichopoda and H. annuus. Three types of zinc-finger motifs were identified in this clade: CxCxHNH (SlWRKY15, AtWRKY55, and OsWRKY57), CxCxHTC (Ha94651) and CxCxHRH (OsWRKY68 and WRKY17).

Clade 2 contained WRKY TFs from across the plant kingdom, from Physcomitrium patens (e.g., Pp3000) to Prunus persica (e.g., Ppe74300). There were two main zinc-finger structure types identified in Clade 2: CxCxHNH (e.g., WRKY71, Mp6s0129, Spol02923, and Aco99600) and CxCxHTH (e.g., WRKY48, Zm07329, OsWRKY11, and Spol04568). A WRKY TF lacking a zinc-finger motif, OsWRKY52, was also located in Clade 2.

In Clade 3, the major zinc-finger motif types were CxCxHNH (e.g., Ha38981, WRKY9, and F215A8), CxCxHTH (e.g., Pp15040 and Pp32160) and CxCxHTC (e.g., WRKY38, SlWRKY55 and WRKY46). Notably, no WRKY TFs from the monocots was included in Clade 3.

In Clade 4, the WRKY TFs containing two WRKY domains were dominant; these were found in embryophytes, monocots, and dicots (purple branches in Figure 1). The predominant zinc-finger motif was CxCxHNH-CxCxHNH (e.g., Pp23590, OsWRKY78, and WRKY1). The zinc-finger motif in the WRKY TFs with only one WRKY domain was CxCxHNH (e.g., WRKY10).

Lastly, Clade 5 comprised only TFs with a single WRKY domain and a single zinc-finger motif, and these were assigned to monocot (brown-yellow branches in Figure 1) and dicot subclades (pale blue branches in Figure 1). Within the Clade, the main zinc-finger motif types were CxCxHNH (e.g., Zm39532, Spol03061, SlWRKY27, and Ha36511), CxCxHSH (e.g., OsWRKY5) and CxCxHTC (e.g., OsWRKY20 and Zm23616). There were also WRKY TFs without a complete zinc-finger motif (e.g., WRKY18) in the Clade 5.

Finally, the long branches observed in the reconstructed WRKY phylogeny suggest a high degree of nucleotide variation across the plant kingdom.

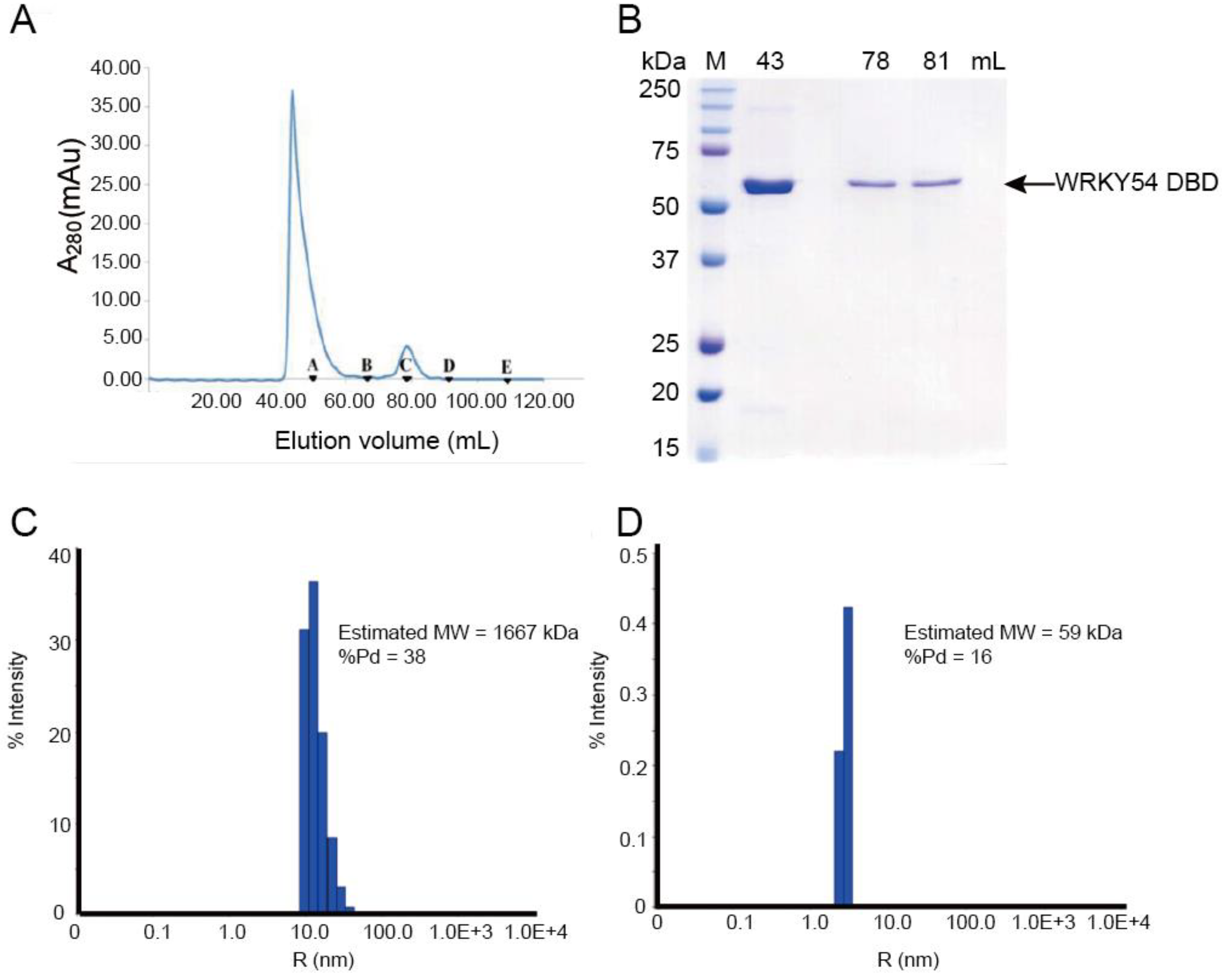

4. The Single WRKY Domain of WRKY54 Exists as Both a Monomer and in an Aggregated Form In Vitro

To study the binding ability of the single WRKY domain in Clade 3, the recombinant WRKY54 protein was expressed and purified. In the first trial, the full length of the WRKY54 recombinant protein exhibited an aggregated form with no DNA binding ability in solution after cell lysis. The DNA binding domain of WRKY54 from residues 133–224 was constructed. After protein expression and purification, the recombinant WRKY54 DBD protein exhibited two forms—an aggregated form and a monomeric form—that corresponded to two major peaks in the SEC elution profile (Figure 2A). SDS-PAGE showed that main protein product size of the eluted solution collected at 43 mL, 78 mL, and 81 mL was 50–75 kDa (Figure 2B). To verify the oligomerization state of the WRKY54 DBD, protein solutions collected at 43, 78 and 81 mL were subjected to DLS. The protein solutions collected at 78 and 81 mL may have contained the same protein product, so these solutions were pooled for the DLS analysis. The DLS results showed that the molecular mass of the WRKY54 DBD fraction collected at 43 mL was 1667 kDa, suggesting that the WRKY54 DBD in this fraction was in the aggregate form (Figure 2C). In contrast, the protein size measured in the pooled solutions collected at 78 and 81 mL was 59 kDa, suggesting that the WRKY54 DBD in these fractions was in the monomer form (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. The WRKY54 DNA-binding domain (DBD) tends to form both aggregated and monomeric states in vitro. (A) Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) analysis reveals that the WRKY54 DBD could be eluted as either an aggregated or a monomeric form in elution buffer (30 mM HEPES, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.5). Black triangles denote the protein standards: A, thyroglobulin (670 kDa); B, γ-globulin (158 kDa); C, ovalbumin (44 kDa); D, myoglobin (17 kDa); E, vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa). (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of eluted WRKY54 DBD recombinant protein. M, protein markers; 43, 78, and 81 mL represent the peaks of WRKY54 protein elution in the SEC analysis. (C) Dynamic light scattering results revealed the aggregated form of the WRKY54 DBD protein at an elution volume of 43 mL (molecular weight [MW]: 1667 kDa). (D) Dynamic light scattering results revealed the monomeric form of the WRKY54 DBD protein at an elution volume of 78–81 mL (MW: 59 kDa).

5. WRKY54 DNA-Binding Domain Can Bind to W4 Box from SAG12 Upstream Sequence

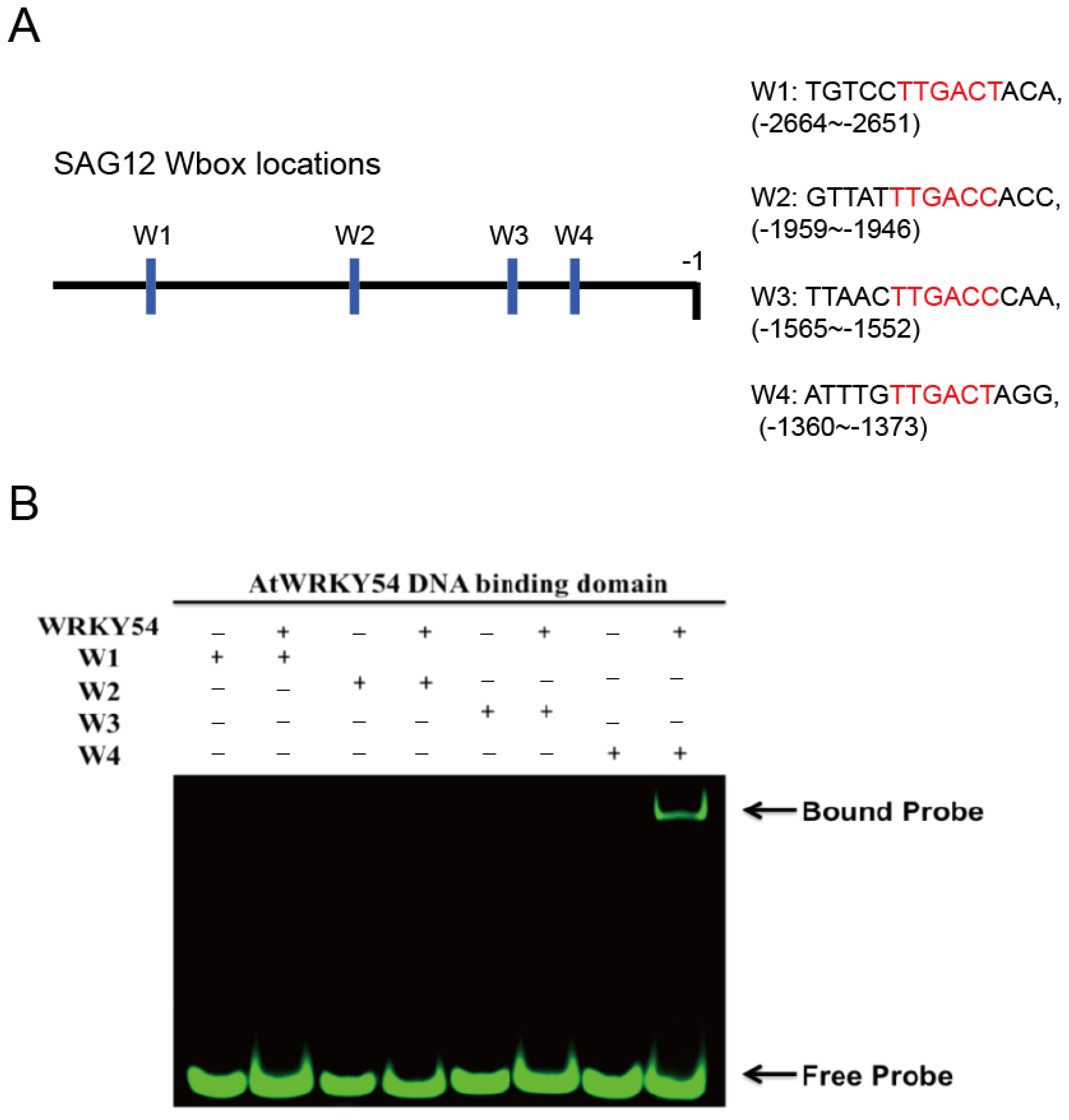

It is known that WRKY TFs bind to the DNA sequence named W-box (5′-TTGAC-C/T-3′). However, several sequences upstream of the promoters triggered by WRKY TFs contain W-box–centered sequences with TTGACC or TTGACT. Therefore, the researchers first used a fEMSA to examine whether the WRKY54 DBD can bind to W-box sequences with TTGACC or TTGACT from the SAG12 upstream region. Four types of W-box (W1–W4) obtained from SAG12 upstream regions were used as probes (Figure 3A). Those four types of W-box were labeled with fluorescein and incubated with purified WRKY54 DBD protein. The results confirmed binding of the WRKY54 DBD protein to W4, but no binding to W1, W2, or W3 (Figure 3B). These four W-box sequences differ in the nucleotides at either the 5′ or the 3′ flanking region (Figure 3A). To examine whether the nucleotides located adjacent to W4 box affect the binding ability of WRKY54, researchers designed a series of W4 probes.

Figure 3. Binding preference of WRKY54 DNA binding domain (DBD), as revealed by fluorescence-based electrophoretic mobility shift assay (fEMSA). (A) Location and nucleotide composition of the four identified W-box regions adjacent to the SAG12 gene. Conserved W-box regions are labelled in red. (B) W1–W4 correspond to the four W-box regions shown in (A). The fEMSA of the four fluorescence-labeled W-box regions incubated with purified recombinant WRKY54 DBD protein.

6. WRKY54 Can Bind to the W4 of SAG12 In Vivo

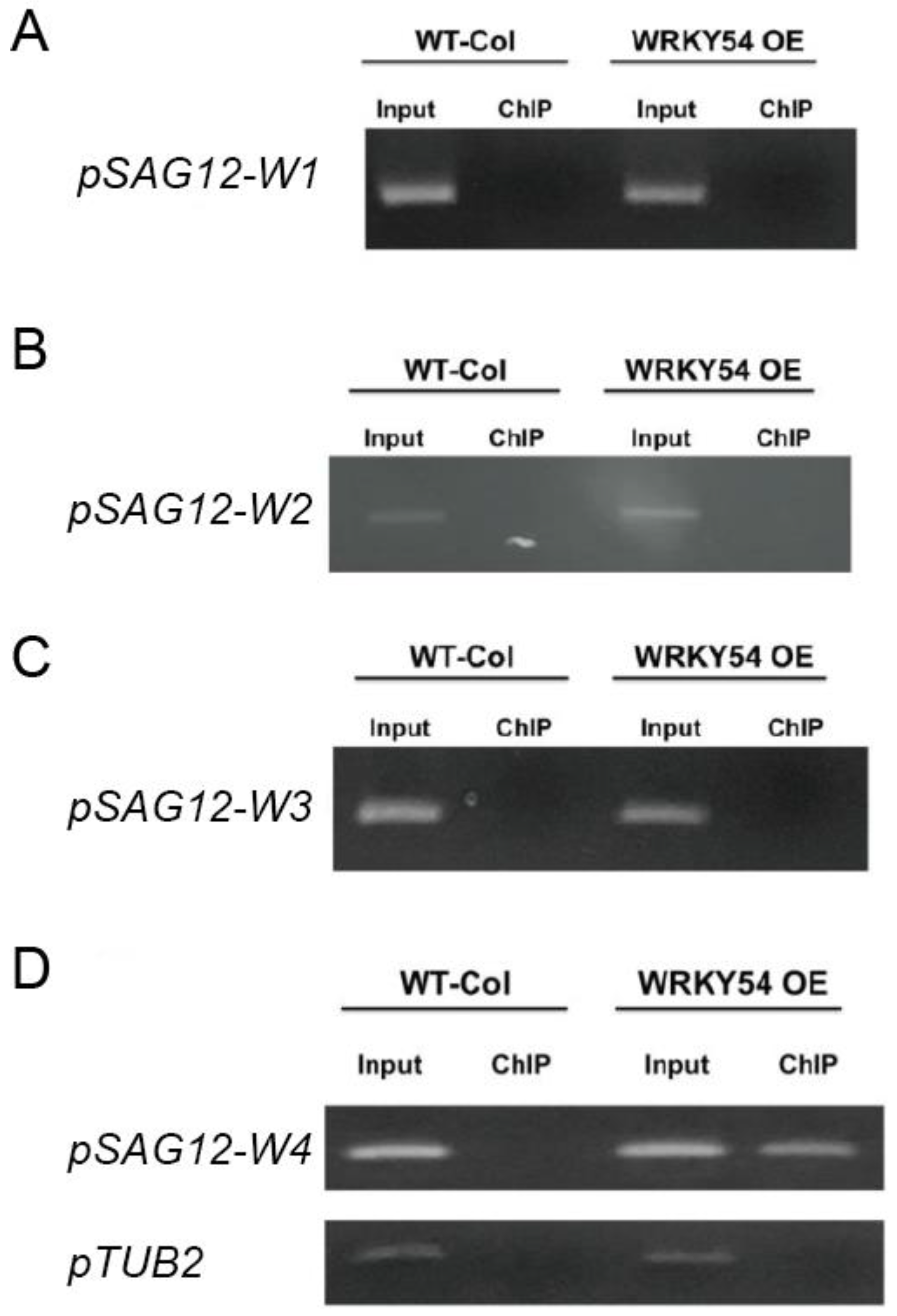

The ChIP-PCR technique was used to confirm whether WRKY54 binds specifically to W4 in vivo. Consistent with the fEMSA results, WRKY54 failed to bind to W1–W3 in either wild type Arabidopsis or a WRKY54-overexpression line (Figure 4A–C). However, for W4, a clear banding pattern could be seen for the WRKY54-overexpression line, although it was weaker for the wild type (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Specific binding ability of WRKY54 to the four W-box types in SAG12 in vivo. (A–D) pSAG12-W1 to pSAG12-W4 represent the W1–W4 regions shown in Figure 3. WT-col: wild-type Arabidopsis. WRKY54 OE: WRKY54-overexpression line. Input: PCR products amplified from genomic DNA. ChIP: PCR products amplified from rabbit-anti-myc precipitation DNA. Left panels represent the ChIP-PCR verification of the relevant W-box type from A. thaliana Columbia-0. Right panels represent ChIP-PCR verification of the relevant W-box type from the WRKY54 OE line.

7. Length of the Flanking Region Adjacent to W-Box Affects the Binding Ability of WRKY54 DBD

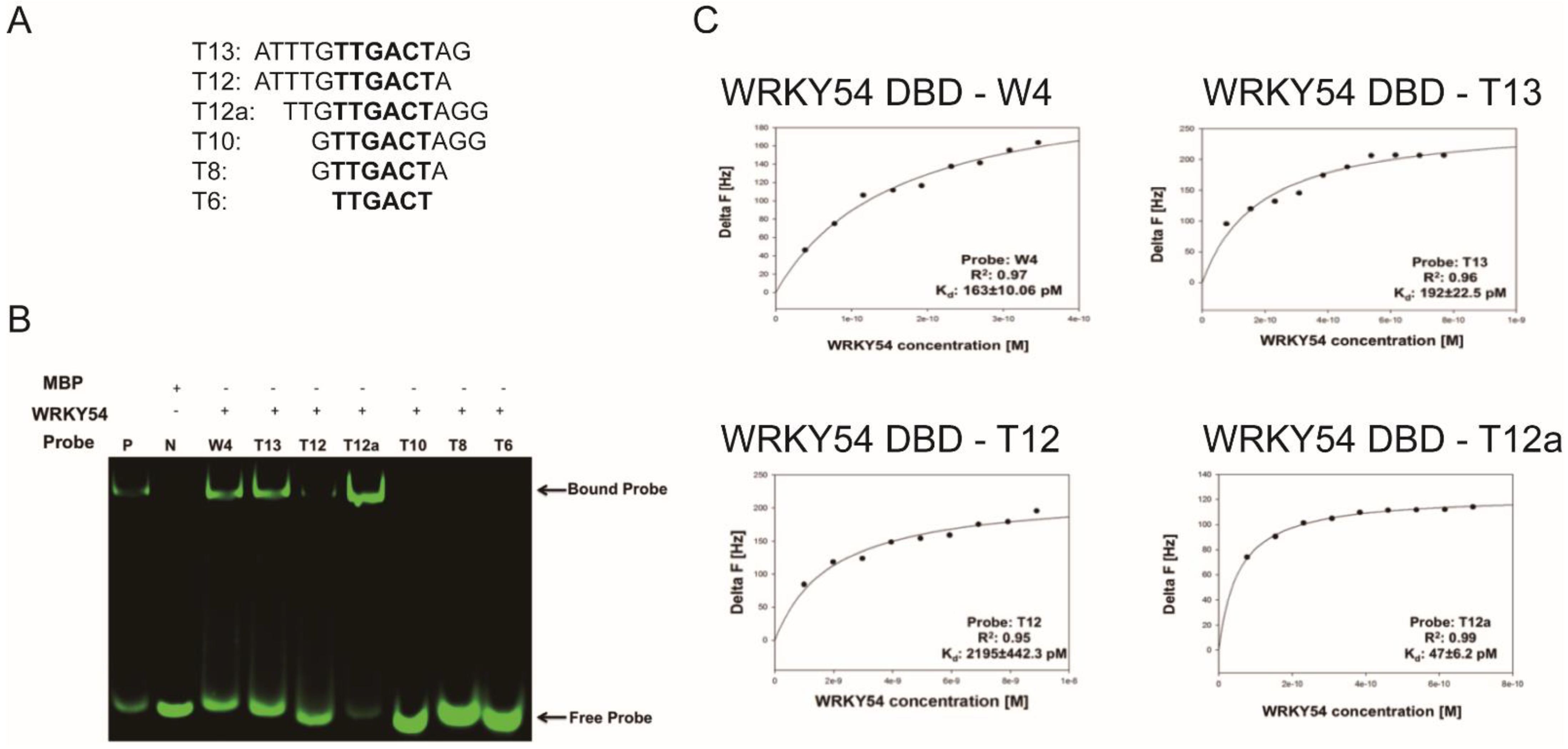

The researchers then examined whether the composition of the flanking region adjacent to W4 box affected the specific binding ability of the WRKY54 DBD. Six artificial W4 variants were synthesized for this purpose (Figure 5A). Clear banding shift patterns were observed for the WRKY54 DBD–W4, WRKY54 DBD–T13, and WRKY54 DBD–T12a pairs (Figure 5B). In contrast, the WRKY54 DBD–T12 pair displayed a relatively weak banding shift. For the pairs involving T6, T8, and T10, no banding shift was observed, suggesting that the WRKY54 DBD was unable to bind to those artificial W4-like nucleotides (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Length preference of WRKY54 DNA-binding domain (DBD) for W4 variants. (A) Artificially truncated flanking region of the W4 box sequences used to identify the nucleotide preference of the WRKY54 DBD. (B) P, positive control; N, maltose-binding protein (MBP) only; W4, the W4 box shown in Figure 3A. The fEMSA banding shift patterns observed when combining WRKY54 DBD protein with fluorescence-labeled W4 and W4-like probes. (C) Plotted curves for the binding assays of the WRKY54 DBD protein with W4 and the artificially truncated W4-like nucleotides.

The QCM was then used to examine the binding constants of the WRKY54 DBD to W4 and the W4-like nucleotides (Table 2). The Kd value obtained from the W4–WRKY54 DBD pair was 163 ± 10.06 pM. The Kd values were 192 ± 22.5 pM and 2195 ± 442.3 pM for the T13–WRKY54 DBD and T12–WRKY54 DBD pairs, respectively. When the 5′-end nucleotides were removed, the Kd values were 47 ± 6.2 pM (T12a–WRKY54 DBD pair) and 68 ± 11.73 pM (T13–WRKY54 DBD pair; Table 1, Figure 5C). There were no signals detected in the T6, T8, or T10 pairs. These results showed that a flanking region with at least three nucleotides at the 5′ end of TTGACT is required for the binding of the WRKY54 DBD.

Table 2. Dissociation rate constant (Kd) values measured for W4– and W4-like–WRKY54 DBD pairs.

| Probes | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | R2 | Kd (pM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| W4 | ATTTGTTGACTAGG | 0.97 | 163 ± 10.06 |

| T13 | ATTTGTTGACTAG | 0.96 | 192 ± 22.5 |

| T12 | ATTTGTTGACTA | 0.95 | 2195 ± 442.3 |

| T12a | TTGTTGACTAGG | 0.99 | 47 ± 6.2 |

| T10 | GTTGACTAGG | – | N.D. |

| T8 | GTTGACTA | – | N.D. |

| T6 | TTGACT | – | N.D. |

N.D., nondetectable.

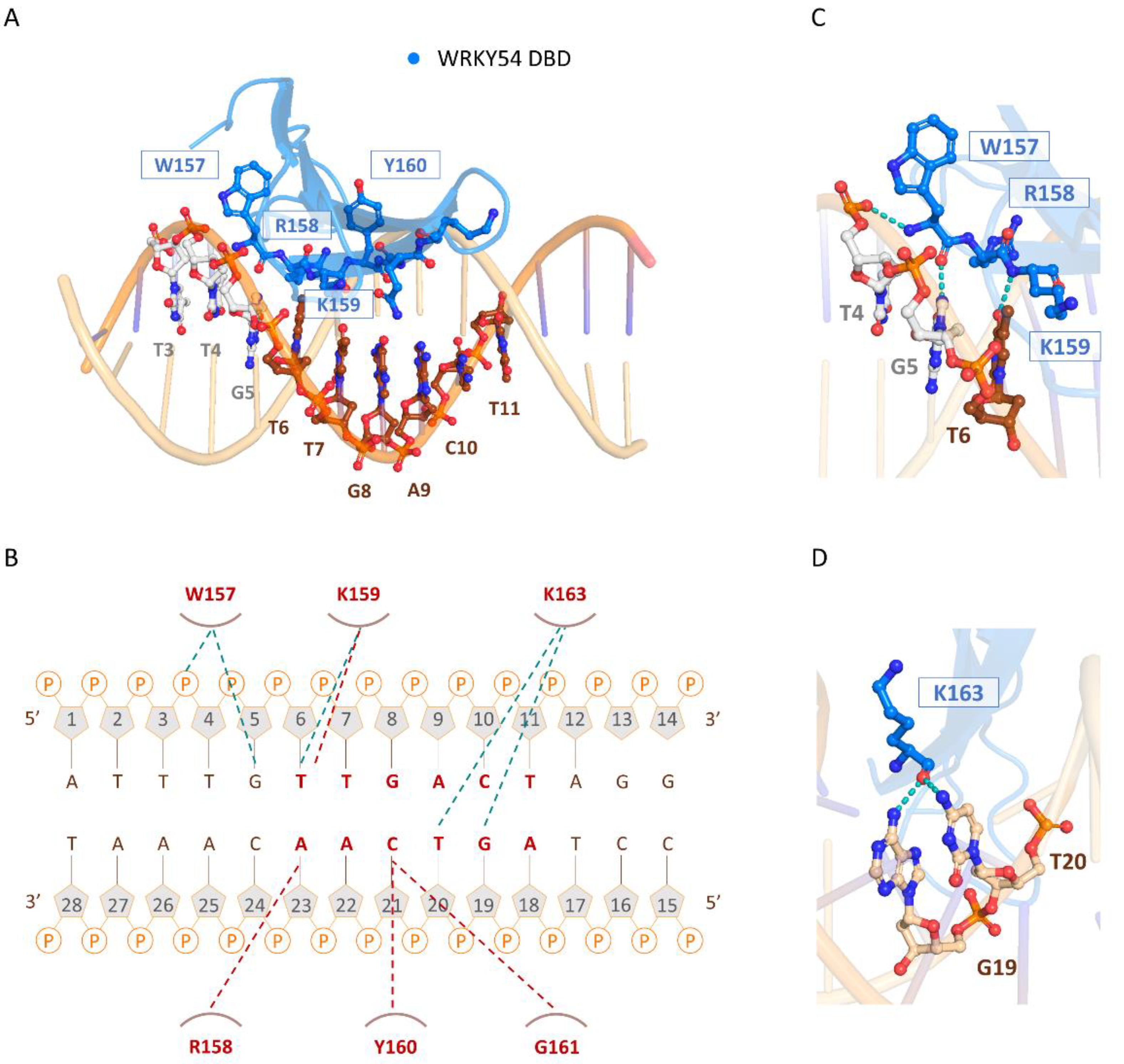

8. Structural Insights into the DNA Binding of WRKY54 to W-Box

The three-dimensional model of the docked structure of the WRKY54 DBD revealed a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet with the conserved WRKYGQK (W157, R158, K159, Y160, G161, Q162, and K163) motif located in the β1 strand. Insertion of the four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet into the major groove of W-box DNA permits extensive interactions between the residues of the WRKY54 DBD and the DNA nucleotides (5′-ATTTGTTGACTAGG-3′, W-box sequence underlined), as illustrated in Figure 6A. At the protein–DNA interface, intermolecular contacts between the WRKY54 DBD and the W4 nucleotides are primarily between the conserved residues W157, R158, K159, Y160, G161, and K163 on the β1 strand and dT4–dT7 and dG19–dA23 on the DNA. In this context, molecular interactions are mediated mainly by the formation of apolar contacts and H-bonds between the conserved residues of the WRKYRQK binding motif (W157, R158, K159, and Y160) and the DNA nucleotides dG5, dT6, dG19, dT20, dC21 and dA22 (Figure 6B). In this postulated scenario, intermolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions formed between W157 and dT4 and/or dG5; K159 and dT6; and K163 and dG19 and/or dT20 are involved in the specific binding of the WRKY54 DBD to the W-box DNA sequence (Figure 6C,D). Based on the binding mode of the WRKY54 DBD to W4, a 5′ flanking region of W-box with at least three additional nucleotides is thus required for WRKY54 binding.

Figure 6. The binding mode of the WRKY54 DNA-binding domain (DBD) to W4 DNA. (A) Overall structure of the WRKY54 DBD and W4 complex. The nucleotides and amino acids involved in the protein–DNA interaction are displayed as a ball-and-stick model. (B) Summary of the interaction between the WRKY54 DBD and W4. The apolar interactions are indicated by red lines and the hydrogen bonds are represented by green lines. (C,D) Close-up view of the W4–WRKY54 DBD interaction interface. Hydrogen bonds are indicated with green dotted lines.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23052895

References

- Maeo, K.; Hayashi, S.; Kojima-Suzuki, H.; Morikami, A.; Nakamura, K. Role of Conserved Residues of the WRKY Domain in the DNA-binding of Tobacco WRKY Family Proteins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 2428–2436.

- Eulgem, T.; Rushton, P.J.; Robatzek, S.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 199–206.

- Mohanta, T.K.; Park, Y.H.; Bae, H. Novel Genomic and Evolutionary Insight of WRKY Transcription Factors in Plant Lineage. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37309.

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Hao, B.; Kaushik, S.K.; Pan, Y. WRKY gene family evolution in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetica 2011, 139, 973–983.

- Chen, X.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Guo, Z. WRKY transcription factors: Evolution, binding, and action. Phytopathol. Res. 2019, 1, 13.

- Besseau, S.; Li, J.; Palva, E.T. WRKY54 and WRKY70 co-operate as negative regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 2667–2679.

- Miao, Y.; Laun, T.; Zimmermann, P.; Zentgraf, U. Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 55, 853–867.

- Ulker, B.; Shahid Mukhtar, M.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY70 transcription factor of Arabidopsis influences both the plant senescence and defense signaling pathways. Planta 2007, 226, 125–137.

- Hinderhofer, K.; Zentgraf, U. Identification of a transcription factor specifically expressed at the onset of leaf senescence. Planta 2001, 213, 469–473.

- Ciolkowski, I.; Wanke, D.; Birkenbihl, R.P.; Somssich, I.E. Studies on DNA-binding selectivity of WRKY transcription factors lend structural clues into WRKY-domain function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 68, 81–92.

- Cheng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Taylor, I.A.; Peng, Y.L.; Wang, D.; Liu, J. Structural basis of dimerization and dual W-box DNA recognition by rice WRKY domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4308–4318.

- Rushton, P.J.; Macdonald, H.; Huttly, A.K.; Lazarus, C.M.; Hooley, R. Members of a new family of DNA-binding proteins bind to a conserved cis-element in the promoters of alpha-Amy2 genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995, 29, 691–702.

- Rinerson, C.I.; Rabara, R.C.; Tripathi, P.; Shen, Q.J.; Rushton, P.J. The evolution of WRKY transcription factors. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 66.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!