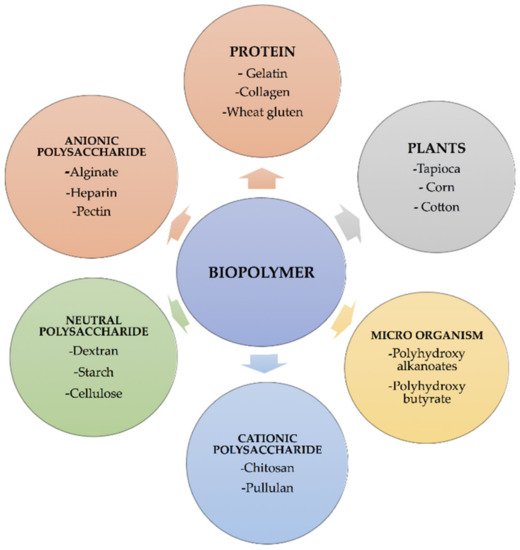

Biopolymers are the organic substances present in natural sources. The term biopolymer originates from the Greek words bio and polymer, representing nature and living organisms. Large macromolecules made up of numerous repeating units are known as biopolymers. As per the IUPAC definition, a macromolecule defines a single molecule. The biopolymers are found to be biocompatible and biodegradable, making them useful in different applications, such as edible films, emulsions, packaging materials in the food industry, and as drug transport materials, medical implants like medical implants organs, wound healing, tissue scaffolds, and dressing materials in pharmaceutical industries.

- biopolymers

- medical applications

1. Sources of Biopolymers

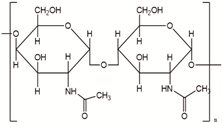

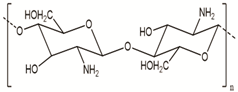

| Biopolymers | Sources | Structure | Reference (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitin | Corals, horseshoe worms, lamp shells, sponges, squid, cuttlefish, and clams are examples of aquatic species |  |

[17][18] |

| Chitosan | Fungi, mollusks, algae, crustaceans, and insects |  |

[17][19] |

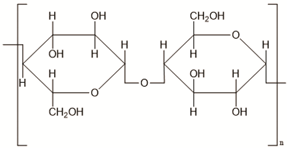

| Cellulose | Agricultural trashes, such as Seaweed, rice husk, and sugarcane bagasse. Plant sources like wood, bamboo, sugarbeet, banana rachis, potato tubers, cotton, fique, kapok, agave, jute, kenaf, flax, hemp, vine, sisal, coconut, grass, wheat, rice, and barley |

|

[20] |

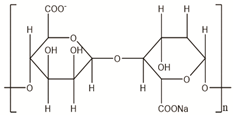

| Alginate | Seawood |  |

[21] |

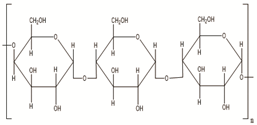

| Starch | Potatoes, maize, cassava, rice, sorghum, banana wheat, yams |  |

[22] |

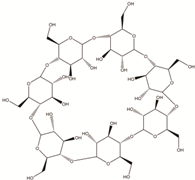

| Cyclodextrin | Starch sources like tapioca, potato, wheat, rice, and corn |  |

[23] |

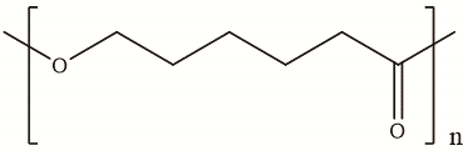

| Polycaprolactone | Polycondensation of ε -caprolactone |

|

[24] |

2. Biopolymers for Medical Applications

| Biopolymer | Medical Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Surface coating for tissue culture plates | [40] |

| Simple gels for cell culture | ||

| Alginate | Regenerative medicine | [41] |

| Tissue engineering | ||

| Hyaluronic acid | Treatment and lubrication of damaged joints | [42] |

| Cutaneous and corneal wound healing | ||

| Fibrin | Blood clotting, wound healing, and tumor growth | [43] |

| Hemostatic agent, sealant, and surgical glue | ||

| Silk fibroin | Regenerative medicine Treatment of wounds, bioengineering of tissues |

[44] |

| Agarose | Skeletal tissues regeneration, kidney and fibroblast encapsulation |

[45] |

| Carrageenan | Skeletal tissues regeneration, cell delivery system |

[46] |

| Fibronectin | Wound healing, cardiac repair, bone regeneration |

[47] |

| PHAs | Drug delivery systems, one tissue regeneration, |

[48] |

| Elastin | soft-tissue reconstruction, orthopedics and cell encapsulation |

[49] |

| Keratin | Cornea tissue engineering, skin regeneration |

[50] |

| Starch | Bone and cartilage regeneration, spinal cord injury treatment |

[51] |

2.1. Biomedical Applications of Protein-Based Biopolymers

2.2. Chitosan in Medical Applications

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/polym14050983

References

- Awad, Y.M.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Ok, Y.S.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effects of polyacrylamide, biopolymer and biochar on the decomposition of14C-labelled maize residues and on their stabilization in soil aggregates. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2013, 64, 488–499.

- Karmanov, A.P.; Kanarsky, A.V.; Kocheva, L.S.; Belyy, V.A.; Semenov, E.I.; Rachkova, N.G.; Bogdanovich, N.I.; Pokryshkin, S.A. Chemical structure and polymer properties of wheat and cabbage lignins–Valuable biopolymers for biomedical applications. Polymer 2021, 220, 123571.

- Tanamool, V.; Imai, T.; Danvirutai, P.; Kaewkannetra, P. An alternative approach to the fermentation of sweet sorghum juice into biopolymer of poly-β-hydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) by newly isolated, Bacillus aryabhattai PKV01. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2013, 18, 65–74.

- Gutiérrez, T.J.; Pérez, E.; Guzmán, R.; Tapia, M.S.; Famá, L. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Native and Modified by Crosslinking, Dark-Cush-Cush Yam (Dioscorea trifida) and Cassava (Manihot esculenta) Starch. J. Polym. Biopolym. Phys. Chem. 2014, 2, 1–5.

- Perotti, G.F.; Tronto, J.; Bizeto, M.A.; Izumi, C.M.S.; Temperini, M.L.A.; Lugão, A.B.; Parra, D.F.; Constantino, V.R.L. Biopolymer-Clay Nanocomposites: Cassava Starch and Synthetic Clay Cast Films. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2013, 25, 320–330.

- Borah, P.P.; Das, P.; Badwaik, L.S. Ultrasound treated potato peel and sweet lime pomace based biopolymer film development. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 36, 11–19.

- Redondo-Gómez, C.; Rodríguez Quesada, M.; Vallejo Astúa, S.; Murillo Zamora, J.P.; Lopretti, M.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R. Biorefinery of Biomass of Agro-Industrial Banana Waste to Obtain High-Value Biopolymers. Molecules 2020, 25, 3829.

- Abral, H.; Dalimunthe, M.H.; Hartono, J.; Efendi, R.P.; Asrofi, M.; Sugiarti, E.; Sapuan, S.M.; Park, J.-W.; Kim, H.-J. Characterization of Tapioca Starch Biopolymer Composites Reinforced with Micro Scale Water Hyacinth Fibers. Starch-Stärke 2018, 70, 1700287.

- Lauer, M.K.; Tennyson, A.G.; Smith, R.C. Inverse vulcanization of octenyl succinate-modified corn starch as a route to biopolymer–sulfur composites. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 2391–2397.

- Aguilar, N.M.; Arteaga-Cardona, F.; de Anda Reyes, M.E.; Gervacio-Arciniega, J.J.; Salazar-Kuri, U. Magnetic bioplastics based on isolated cellulose from cotton and sugarcane bagasse. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 238.

- Yu, P. Molecular chemical structure of barley proteins revealed by ultra-spatially resolved synchrotron light sourced FTIR microspectroscopy: Comparison of barley varieties. Biopolymers 2007, 85, 308–317.

- Flaris, V.; Singh, G. Recent developments in biopolymers. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2009, 15, 1–11.

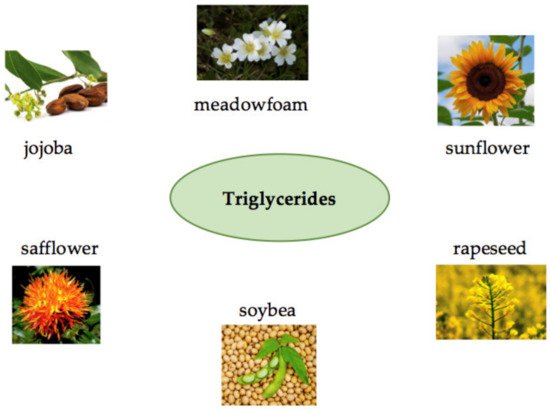

- Sharma, V.; Kundu, P.P. Addition polymers from natural oils—A review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 983–1008.

- Muhamad, I.I.; Sabbagh, F.; Abdul Karim, N. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Valuable Secondary Metabolite Produced in Microorganisms and Plants. In Plant Secondary Metabolites, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: Oakville, MO, USA, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 205–234.

- Mojaveryazdi, F.S.; Muhamad, I.I.; Rezania, S.; Benham, H. Importance of Glucose and Pseudomonas in Producing Degradable Plastics. J. Teknol. 2014, 69, 7–10.

- Udayakumar, G.P.; Muthusamy, S.; Selvaganesh, B.; Sivarajasekar, N.; Rambabu, K.; Sivamani, S.; Sivakumar, N.; Maran, J.P.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Ecofriendly biopolymers and composites: Preparation and their applications in water-treatment. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 52, 107815.

- Elieh-Ali-Komi, D.; Hamblin, M.R. Chitin and Chitosan: Production and Application of Versatile Biomedical Nanomaterials. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 411–427.

- Satitsri, S.; Muanprasat, C. Chitin and Chitosan Derivatives as Biomaterial Resources for Biological and Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 5961.

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256.

- Farooq, A.; Patoary, M.K.; Zhang, M.; Mussana, H.; Li, M.; Naeem, M.A.; Mushtaq, M.; Farooq, A.; Liu, L. Cellulose from sources to nanocellulose and an overview of synthesis and properties of nanocellulose/zinc oxide nanocomposite materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 1050–1073.

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate: Properties and biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–126.

- Carvalho, A.J.F. Starch: Major Sources, Properties and Applications as Thermoplastic Materials. In Monomers, Polymers and Composites from Renewable Resources; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 321–342.

- Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, F.; Gu, Z.; Du, G.; Wu, J.; Chen, J. γ-Cyclodextrin: A review on enzymatic production and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 77, 245–255.

- Espinoza, S.M.; Patil, H.I.; San Martin Martinez, E.; Casañas Pimentel, R.; Ige, P.P. Poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL), a promising polymer for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications: Focus on nanomedicine in cancer. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2019, 69, 85–126.

- Gutierrez Cisneros, C.; Bloemen, V.; Mignon, A. Synthetic, Natural, and Semisynthetic Polymer Carriers for Controlled Nitric Oxide Release in Dermal Applications: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 760.

- Neuendorf, R.E.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Adhesion between biodegradable polymers and hydroxyapatite: Relevance to synthetic bone-like materials and tissue engineering scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1288–1296.

- Chen, Y.; Hung, S.-T.; Chou, E.; Wu, H.-S. Review of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Materials and other Biopolymers for Medical Applications. Mini Rev. Org. Chem. 2018, 15, 105–121.

- Tsai, C.-H.; Wang, P.-Y.; Lin, I.C.; Huang, H.; Liu, G.-S.; Tseng, C.-L. Ocular Drug Delivery: Role of Degradable Polymeric Nanocarriers for Ophthalmic Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2830.

- Park, S.-B.; Lih, E.; Park, K.-S.; Joung, Y.K.; Han, D.K. Biopolymer-based functional composites for medical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 68, 77–105.

- Yahya, E.B.; Amirul, A.A.; Khalil, H.P.S.A.; Olaiya, N.G.; Iqbal, M.O.; Jummaat, F.; Atty Sofea, A.K.; Adnan, A.S. Insights into the Role of Biopolymer Aerogel Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Polymers 2021, 13, 1612.

- Chaikof, E.L.; Matthew, H.; Kohn, J.; Mikos, A.G.; Prestwich, G.D.; Yip, C.M. Biomaterials and Scaffolds in Reparative Medicine. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 961, 96–105.

- Song, W.; Lima, A.C.; Mano, J.F. Bioinspired methodology to fabricate hydrogel spheres for multi-applications using superhydrophobic substrates. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 5868–5871.

- Hook, A.L.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R.; Williams, P.; Davies, M.C.; Alexander, M.R. High throughput methods applied in biomaterial development and discovery. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 187–198.

- Hassan, N.; Verdinelli, V.; Ruso, J.M.; Messina, P.V. Assessing structure and dynamics of fibrinogen films on silicon nanofibers: Towards hemocompatibility devices. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 6582–6592.

- Pattanashetti, N.A.; Heggannavar, G.B.; Kariduraganavar, M.Y. Smart Biopolymers and their Biomedical Applications. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 12, 263–279.

- Reddy, N.; Reddy, R.; Jiang, Q. Crosslinking biopolymers for biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 362–369.

- Wróblewska-Krepsztul, J.; Rydzkowski, T.; Michalska-Pożoga, I.; Thakur, V.K. Biopolymers for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications: Recent Advances and Overview of Alginate Electrospinning. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 404.

- Gagliardi, A.; Giuliano, E.; Venkateswararao, E.; Fresta, M.; Bulotta, S.; Awasthi, V.; Cosco, D. Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery to Solid Tumors. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 17.

- Sabbagh, F.; Muhamad, I.I. Production of poly-hydroxyalkanoate as secondary metabolite with main focus on sustainable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 95–104.

- Tripathi, D.; Rastogi, K.; Tyagi, P.; Rawat, H.; Mittal, G.; Jamini, A.; Singh, H.; Tyagi, A. Comparative Analysis of Collagen and Chitosan-based Dressing for Haemostatic and Wound Healing Application. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 76.

- Álvarez-Castillo, E.; Aguilar, J.M.; Bengoechea, C.; López-Castejón, M.L.; Guerrero, A. Rheology and Water Absorption Properties of Alginate–Soy Protein Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1807.

- Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Dykas, K.; Felkle, D.; Karnas, K.; Khachatryan, G.; Karewicz, A. Hyaluronic Acid-Silver Nanocomposites and Their Biomedical Applications: A Review. Materials 2021, 15, 234.

- Nelson, D.W.; Gilbert, R.J. Extracellular Matrix-Mimetic Hydrogels for Treating Neural Tissue Injury: A Focus on Fibrin, Hyaluronic Acid, and Elastin-Like Polypeptide Hydrogels. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2101329.

- Grabska-Zielińska, S.; Sionkowska, A. How to Improve Physico-Chemical Properties of Silk Fibroin Materials for Biomedical Applications?—Blending and Cross-Linking of Silk Fibroin—A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 1510.

- Mahmood, A.; Patel, D.; Hickson, B.; DesRochers, J.; Hu, X. Recent Progress in Biopolymer-Based Hydrogel Materials for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1415.

- Khaliq, T.; Sohail, M.; Minhas, M.U.; Ahmed Shah, S.; Jabeen, N.; Khan, S.; Hussain, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Kousar, M.; Rashid, H. Self-crosslinked chitosan/κ-carrageenan-based biomimetic membranes to combat diabetic burn wound infections. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 197, 157–168.

- Klavert, J.; van der Eerden, B.C.J. Fibronectin in Fracture Healing: Biological Mechanisms and Regenerative Avenues. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 274.

- Goswami, M.; Rekhi, P.; Debnath, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates Granules: An Approach Targeting Biopolymer for Medical Applications and Developing Bone Scaffolds. Molecules 2021, 26, 860.

- Sarangthem, V.; Singh, T.D.; Dinda, A.K. Emerging Role of Elastin-Like Polypeptides in Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Wound Care 2021, 10, 257–269.

- Sellappan, L.K.; Anandhavelu, S.; Doble, M.; Perumal, G.; Jeon, J.-H.; Vikraman, D.; Kim, H.-S. Biopolymer film fabrication for skin mimetic tissue regenerative wound dressing applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2020, 71, 196–207.

- Varma, K.; Gopi, S. Biopolymers and their role in medicinal and pharmaceutical applications. In Biopolymers and Their Industrial Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 175–191.

- Yadav, P. Biomedical Biopolymers, their Origin and Evolution in Biomedical Sciences: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZE21.

- Bhatia, M.; Girdhar, A.; Tiwari, A.; Nayarisseri, A. Implications of a novel Pseudomonas species on low density polyethylene biodegradation: An in vitro to in silico approach. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 497.

- Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Du, B.; Han, C.; Hou, Z. Effect of Fullerene Nanoparticle on Tuning Trap Level Distribution of Fullerene/Polyethylene Nanocomposites. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Electrical Materials and Power Equipment (ICEMPE), Guangzhou, China, 7–10 April 2019; pp. 333–336.

- Peters, D.; Kastantin, M.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Karmali, P.P.; Gujraty, K.; Tirrell, M.; Ruoslahti, E. Targeting atherosclerosis by using modular, multifunctional micelles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9815–9819.

- Rebelo, R.; Fernandes, M.; Fangueiro, R. Biopolymers in Medical Implants: A Brief Review. Procedia Eng. 2017, 200, 236–243.

- Nitta, S.; Numata, K. Biopolymer-Based Nanoparticles for Drug/Gene Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 1629–1654.

- Nagarajan, S.; Abessolo Ondo, D.; Gassara, S.; Bechelany, M.; Balme, S.; Miele, P.; Kalkura, N.; Pochat-Bohatier, C. Porous Gelatin Membrane Obtained from Pickering Emulsions Stabilized by Graphene Oxide. Langmuir 2018, 34, 1542–1549.

- Biscarat, J.; Bechelany, M.; Pochat-Bohatier, C.; Miele, P. Graphene-like BN/gelatin nanobiocomposites for gas barrier applications. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 613–618.

- Li, Y.; Rodrigues, J.; Tomás, H. Injectable and biodegradable hydrogels: Gelation, biodegradation and biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2193–2221.

- Kharkar, P.M.; Kiick, K.L.; Kloxin, A.M. Designing degradable hydrogels for orthogonal control of cell microenvironments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7335–7372.

- Sridhar, R.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Madhaiyan, K.; Amutha Barathi, V.; Lim, K.H.C.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrosprayed nanoparticles and electrospun nanofibers based on natural materials: Applications in tissue regeneration, drug delivery and pharmaceuticals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 790–814.

- Jammalamadaka, U.; Tappa, K. Recent Advances in Biomaterials for 3D Printing and Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 22.

- Lee, C.H.; Singla, A.; Lee, Y. Biomedical applications of collagen. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 221, 1–22.

- Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Giménez, B.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Montero, M.P. Functional and bioactive properties of collagen and gelatin from alternative sources: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1813–1827.

- Gaspar-Pintiliescu, A.; Stefan, L.M.; Anton, E.D.; Berger, D.; Matei, C.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Moldovan, L. Physicochemical and Biological Properties of Gelatin Extracted from Marine Snail Rapana venosa. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 589.

- Ak, H.P.S.; Saurabh, C.K.; Nurul Fazita, M.R.; Syakir, M.I.; Davoudpour, Y.; Rafatullah, M.; Abdullah, C.K.; Haafiz, M.M.K.; Dungani, R. A review on chitosan-cellulose blends and nanocellulose reinforced chitosan biocomposites: Properties and their applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 150, 216–226.

- Sharifianjazi, F.; Khaksar, S.; Esmaeilkhanian, A.; Bazli, L.; Eskandarinezhad, S.; Salahshour, P.; Sadeghi, F.; Rostamnia, S.; Vahdat, S.M. Advancements in Fabrication and Application of Chitosan Composites in Implants and Dentistry: A Review. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 155.

- Su, S.; Kang, P.M. Systemic Review of Biodegradable Nanomaterials in Nanomedicine. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 656.