2. Aquaculture in Portugal

Portugal is a traditional fishing country, with a vast Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)—the 20th largest EEZ in the world—and a world-known tradition of high seafood consumption, both in terms of quantity and diversity of products

[4][5][6][7]. Portuguese fish consumption per capita in 2018 was 61.5 kg, making Portugal the major consumer within the European Union member states and the third major consumer worldwide, preceded only by Korea and Norway

[8][9][10]. A seasonal rise in fish consumption can also be associated with intense tourism during summer months, which demands a significant extra supply of such products. The combination of an extremely high demand for seafood, associated to geographic, abundance of marine resources and traditional reasons

[11], result in the import of almost two-thirds of aquatic animals for human consumption. In 2018, Portugal imported 336.5 thousand tonnes of seafood for human consumption, corresponding almost entirely to finfish imports. Cod (including different species of the genus

Gadus) is the main imported finfish, either fresh, frozen or sated, corresponding to 37% of total finfish imports

[12]. The species does not exist in Portuguese waters but has remained a crucial ingredient in the country’s eating habits, also encouraged by the high-quality nutritious profile of the fish, particularly its content in omega-3 fatty acids. In fact, until recent times, providing “cod liver oil” to children as an omega-3 fatty acids’ supplement was very common in Portugal

[13][14].

Although capture fisheries continue to play a vital role in the Portuguese economy, aquaculture has for a long time existed in the country.

Active rudimental aquaculture methods are thought to have been practiced for centuries in mainland Portugal, consisting essentially of the imprisonment of fish juveniles that used transitional systems as nursery areas in salt works and ponds in wetlands, letting them grow to be harvested when at a desirable size for consumption. Aquaculture in continental Portugal remained almost exclusively a familiar activity until around the beginning of the 20th century when it began to be regarded as a potential commercial activity that could contribute to the country’s economy. Rainbow trout and freshwater species were the first to be farmed at a commercial level, but aquaculture in Portugal later evolved to the rearing of mainly marine species.

Despite the mentioned initial advances in aquaculture in Portugal, the activity had a slow development over the years, as fishing has always played an important role in the tradition and economy of the country

[15]. Before the 1970s, 80% of fish aquaculture production in Portugal was of mullets; then, during the 1980s, the production was mostly of freshwater rainbow trout and bivalves in intertidal zones. The aquaculture of marine species did not experience true development until the 1990 decade, focusing at first on the rearing of gilthead seabream and European seabass, and more recently on the rearing of turbot (

Scophthalmus maximus, Linnaeus 1758) and sole (

Solea spp.)

[16].

The development of aquaculture in Portugal took place after the country became a member state of the European Union (EU) in 1986 (at that time, named European Economic Commission). Because aquaculture was a key component of the EU’s Blue Growth Agenda, community funds were attributed to Portugal as a member state for the development of the activity and the Portuguese Government itself invested in aquaculture development as well. The financial support given was intended for the development of research programmes that could enhance knowledge and know-how about aquatic animals’ rearing, the construction of new and more suitable establishments, professional training of farmers and financial support to professional organizations

[15][16][17]. Although Portuguese aquaculture experienced some development in the 1980s, the production decreased significantly in the 1990s, mainly due to a lack of criteria for the application of the available funds and issues in the production methods applied, leading to the unviability of many aquaculture units

[17]. Nonetheless, despite some fluctuations in aquaculture production over the years, there has been a general rising trend in aquaculture production in Portugal, and true expansion in the past couple of years

[4][5][6][7].

Portuguese aquaculture focuses on the production of marine fish and mollusc species, and most facilities are located on the country’s mainland. Although intensive aquaculture has gained true importance recently, especially regarding fish production, most establishments are located and have further expanded in coastal systems, such as estuaries and coastal lagoons, along the country’s mainland coastline. Aquaculture in the Portuguese archipelagos is yet poorly developed—only the Madeira archipelago presents aquaculture production, currently—although efforts are being made to expand the activity in the Madeira islands and promote the development of aquaculture production in the Azores archipelago

[4][5][6][7].

The total marine aquaculture production in Portugal in 2018 was about 13.99 thousand tonnes, accounting for little over 0.50% of Europe’s total aquaculture production

[8][12][4][5][6][7][9]. Compared to other European countries of the EU, Portugal presents a much slower progress in aquaculture production and development, occupying 16th place in the rank of total aquaculture production amongst EU member states in 2018, contributing with less than 1% for the total aquaculture production in terms of volume in the EU

[9][10].

The aquaculture of marine organisms in continental Portugal is essentially carried out in estuaries and wetlands along the coast, especially in the centre and south of the country, resorting to extensive and semi-intensive rearing methods. Although there is potential for the rearing of freshwater organisms, aquaculture activity in Portugal has focused essentially on the production of marine species since recent developments in aquaculture in the 20th century. In fact, freshwater aquaculture in Portugal represented 4.98% of the total aquaculture production in the country in 2018, 10.3% less than the freshwater aquaculture production registered in 2017. Aquaculture production in marine and estuarine systems accounted for the remaining 95% of the production

[4][5][6][7]. The species reared in the mentioned systems, although marine species, frequently enter estuaries and other coastal systems at some point during their development, and are, thus, well-adapted to the environmental conditions. This fact, along with the availability of juveniles for the grow-out and the high market value of such species, makes them the first choices for aquaculture production in coastal systems in Portugal

[15][16][17][18][19]. Although offshore farms are beginning to be implemented, there are still very few establishments operating, and the production from these facilities is yet notably low. As for intensive aquaculture systems, there were 23 establishments operating in Portugal in 2018, mostly aimed for the production of turbot and freshwater rainbow trout

[20], which seem to be lowering in terms of number. Nonetheless, these facilities achieve much higher densities of organisms compared to semi-intensive and extensive systems. In 2011, the total aquaculture production in intensive systems surpassed the production in extensive systems due to a boost in the production of turbot. This species is reared essentially in intensive systems and, in 2011, its production accounted for 3197 tonnes alone, contributing to a total production of 3648 tonnes in intensive systems, while the total production in extensive systems (including fish and molluscs), was 3504 tonnes. In 2013 the production of turbot declined from 4406 to 2353 tonnes, causing the decrease in the volume of aquaculture products from intensive rearing systems, at the same time that mussel and oyster production grew significantly, enabling a new peak of production in extensive systems. From then on, extensive rearing production has risen every year, achieving a new country’s maximum in 2018

[4][5][6][7].

Although the number of establishments using intensive systems of production is lower than those using extensive and semi-intensive systems, the comparison between the volume of production from each system shows that the production capacity is much greater in intensive systems.

Aquaculture production in marine and transitional waters in Portugal surpassed freshwater production for the first time in 1996. It has been the main contributor to the total aquaculture production in the country ever since, representing, in 2018, 95% of the total aquaculture production in Portugal, and reaching, by that year, its peak in production for the time frame issued.

Although intensive aquaculture has recently shown high production outputs for a small number of establishments, semi-intensive and extensive aquaculture are the most commonly used production methods in Portugal. These methods have been abandoned in most European countries while persevering in Portugal, and even experiencing developments in terms of techniques, rearing strategies and culture characteristics. Aquaculture production in the Portuguese archipelagos is carried out along the coast of the islands, in marine water, and, thus, the systems are not exactly transitional systems, compared to the reality on the mainland. Aquaculture production in transitional and marine waters (from offshore and intensive production capturing directly in marine waters) in mainland Portugal appears in official national publications as a whole, and, thus, the production referred to in the next section will provide the sum of the aquaculture production in both systems. The numbers will correspond almost entirely to transitional environments’ production, as marine offshore production is essentially negligible, as afore mentioned.

2.1. Production in Coastal Systems

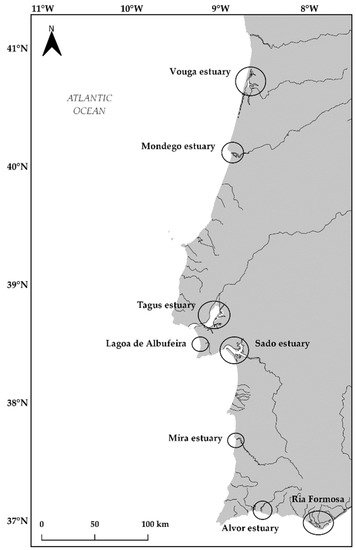

For administrative purposes, mainland Portugal may be divided into five main regions: North, Centre, Lisbon and Tagus Valley, Alentejo and Algarve; there are eight main areas for aquaculture in estuarine systems in Portugal, which are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Main sites for aquaculture production in continental Portugal—circles mark the main sites for production in coastal systems.

One of the most important rivers in Portugal is in the north of the country’s mainland—the Douro river. However, its estuarine system is of small dimensions and not very suitable for the establishment of aquaculture farms. Thus, freshwater aquaculture is the most representative in this region, whereas production in transitional waters accounted for a mean of only 4% of the total aquaculture production in the region during the period between 1999 and 2018

[4][5][6][7].

At the centre of Portugal, there are two important areas for aquaculture in transitional waters: the Vouga estuary and the Mondego estuary.

The Vouga estuary forms a complex coastal lagoon with several natural ponds, consisting of an important wetland, known as Ria de Aveiro. This system covers about 11 ha and has been a Natura 2000 network site since 2014, listed as a Special Protection Area site under the Birds Directive. River Vouga runs through farmlands and urbanized areas, such as the city of Aveiro, during its course, being subjected to the input of many pollutants from runoff and domestic wastewater

[21], and a highly monitored site in an effort to maintain its integrity and good status, nonetheless.

The Mondego estuary has been, since 2005, a site under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Along its course, the Mondego river runs through highly urbanized areas (such as the city of Coimbra), agricultural fields and industrialized areas, until reaching its 1600 ha estuary; the estuary itself is surrounded by urbanized (city of Figueira da Foz) and industrialized areas. The human pressures stated above contribute to the pollution of the river and the estuary, being the main sources of pollution urban wastewater (that is often only partially treated) and chemical products (e.g., pesticides, fertilizers, emerging contaminants) from agricultural water runoff and industrial sewage

[22].

Both Ria de Aveiro and the Mondego estuary are very suitable for aquaculture in extensive and semi-intensive systems, which are known to have been practiced for a long time in these areas, taking advantage of non-operational salt works and modifying them for the production of fish in semi-intensive systems and molluscs in extensive systems. Aquaculture in transitional waters in the Centre region represented a mean of about 97% of the total aquaculture production in the region in the period between 1999 and 2018, accounting, in 2018, for 99.4% of the total aquaculture production in the region. Nonetheless, there are some concerns to be taken into consideration when operating with extensive and semi-intensive rearing methods. Fish farmers need to closely maintain the water quality of their tanks, given that, from time to time, greater amounts of pollutants may reach the estuary and fluctuations in the estuary water quality may potentially affect whole productions

[22][23].

The Lisbon and Tagus Valley area comprises two main areas for aquaculture in brackish waters—the Tagus estuary and Lagoa de Albufeira—and a part of the Sado estuary as well. The Tagus estuary is the largest estuary in Portugal and one of the largest in Europe, with an area of approximately 32,000 ha, and about half of that area being a natural reserve. The city of Lisbon occupies the estuary’s margins, in which numerous human activities operate, such as industries, fisheries and an important harbour, resulting in intense maritime traffic and other associated activities

[24][25]. Aquaculture in the Tagus estuary focuses mainly on the production of oyster.

The Lagoa de Albufeira is a coastal lagoon with an area of 130 ha, with low water renewal and no connection to the ocean after the spring tides, after which a sand barrier is formed. This would isolate the lagoon from water renewal through ocean tides, if it were not for a tidal inlet, which is artificially opened to allow the renewal

[26].

There is virtually no freshwater aquaculture production in the Lisbon and Tagus Valley area, which makes aquaculture in transitional waters the whole of the aquaculture production in the area, apart from the years 1999—with a production of 23 tonnes of freshwater organisms—and 2002, with a production of 3 tonnes of freshwater organisms

[4][5][6][7].

The Sado estuary, comprised between the Lisbon and Tagus Valley and Alentejo regions, has been a natural reserve since 1980, extending for about 24,000 ha, being the second largest estuary in Portugal. Most of its area corresponds to the natural reserve (about 23,160 ha), still, the estuary is subjected to many anthropogenic pressures along its margins and thereabouts, namely several industries (especially on the northern margin), including paper, fertilizers, yeast, food and naval industries, the Setúbal harbour and related activities, the city of Setúbal and copper mines by which the Sado river runs through. Furthermore, the rice fields along the estuary’s margins contribute to the input of pollutants and nutrients to the system. Despite all the pressures stated, the Sado estuary is still very suitable for salt and aquaculture productions

[25][27].

The Alentejo region contains a small area aimed at aquaculture production (about 105 ha) in the Mira estuary; a low impacted system where the main pollution sources are from agriculture fields, tourist-related activities during the summer and urban waste from the small village of Vila Nova de Mil Fontes

[28][29]. The total aquaculture production in Alentejo is in transitional waters, apart from the year 2006, with the production of 4 tonnes of freshwater products (from a total production of 757 tonnes)

[30][20][31][32]. Although not being an area with great aquaculture production potential, the Alentejo region is one of the few regions in Portugal with natural occurrence of the Portuguese oyster (

Magallana angulata)

[15].

Algarve comprises two main areas for aquaculture—the Alvor estuary and Ria Formosa lagunar system. Ria Formosa is a coastal lagoon extending for about 16,300 ha, of which about 2000 ha are occupied by salt works and aquaculture ponds. This coastal lagoon is a Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and Natura 2000 network site and receives water input from small watercourses and from tidal exchanges with the Atlantic Ocean

[33]. Although there are few industrial facilities along the lagoon’s margins, they are heavily urbanized and include some areas of intensive agriculture and animal rearing, which are potential sources of pollution and high nutrient input to the basin (raising the risk for eutrophication of the lagoon)

[34]. The basin is also profoundly modified from its natural structure due to coastal engineering, with the construction of artificial inlets in the western part of the lagoon, construction of dykes to retain freshwater from water streams (such as Ribeira de São Lourenço), two sewage treatment plants operating since 2000 and the Faro Airport constructed on the mudflats

[34].

The Alvor estuary has been a Natura 2000 network site since 2006 and many activities have been developed on it, such as tourism, fishing and aquaculture production. The margins and adjacent land are quite urbanized and used for animal rearing, which may pose pollution threats to the estuary

[35].

All the production in the Algarve region is on brackish and marine waters, and it is the region that most contributes to aquaculture production in Portugal, accounting for 53% of the total aquaculture production in the country in 2018 and for 56% of the production in Portugal in brackish and marine waters in the same year

[20].

Although there are some hatchery establishments in Portugal, these have reduced to just a few units along the years—the highest recorded number of operating hatcheries occurred in 2003, with 12 working hatcheries, but has dropped considerably ever since, with only two operating in 2018. Thus grow-out units are the main aquaculture facility type in Portugal, whose number has been quite consistent over the years, with an average of 1430 operating facilities in the period 2000–2018. From 2017 to 2018, there was a drop in the number of grow-out units in the country—from 1431 to 1400—but this did not result in a drop in production; in turn, with the improvement in rearing techniques, aquaculture production followed a rising trend, as before stated.

2.2. Production Systems

The most common aquaculture production methods in coastal systems in Portugal, as briefly referred to, are extensive and semi-intensive systems, mainly aimed, and respectively, for the rearing of molluscs and fish.

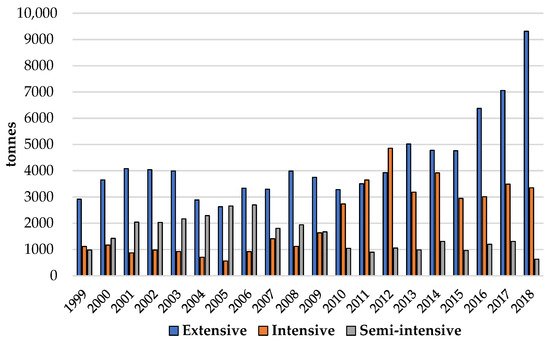

For the time frame issued in the present work, extensive aquaculture production has oscillated somewhat over the years but has always maintained high production numbers, consisting almost exclusively of the rearing of molluscs. Production in semi-intensive systems, especially aimed for the production of fish, has suffered noticeable changes over the years: for example, the break in the production in semi-intensive systems between 2008 and 2011 was probably due to the conversion of semi-intensive facilities for the rearing of fish in units aimed for mollusc production in extensive systems

[4][5][6][7], at the same time that intensive methods were preferred for the rearing of fish. The contribution of extensive, semi-intensive and intensive aquaculture rearing systems for aquaculture production in Portugal is shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Aquaculture production of each of the three rearing systems in the period between 1999 and 2018. Data sources: INE 2000; INE 2002–2019.

2.3. Main Cultured Species

The aquaculture production in Portugal focuses essentially on the rearing of marine fish species, accounting for about 27.6% of the total national aquaculture production, and mollusc production, which accounted for about 67.2% of total national aquaculture production in 2018

[4][5][6][7]. Crustaceans are farmed in low quantities, having little expression in the country’s aquaculture production and, thus, their contribution to aquaculture production in Portugal is included in the percentage of molluscs’ production. Clams, oysters, turbot, mussels, gilthead seabream, rainbow trout and cockles were, by that order, the seven main species cultured in Portugal in 2018; of these, only trout is reared in freshwater systems

[30]. Both turbot and trout are produced using intensive aquaculture methods, not being included in the production of coastal systems, and will not, therefore, be further discussed.

2.3.1. Fish Production in Transitional Systems

According to the most recent data, fish production in transitional systems in semi-intensive or extensive regimes in 2018 was about 511 tonnes, corresponding to 5% of the total aquaculture production in those conditions in Portugal that year

[32]; the main farmed species was gilthead seabream, representing about 60.3% (308 tonnes) of the total fish production in that environment, followed by European seabass, which, together, accounted for 80.5% (508 tonnes) of the total fish production in coastal areas in semi-intensive regimes

[32].

Gilthead seabream was the most cultured marine fish species in Portugal until 2010 when the production of turbot peaked. Seabream is a highly appreciated species in the Portuguese markets and is often reared in polycultures, especially with seabass, which has proven to be very effective

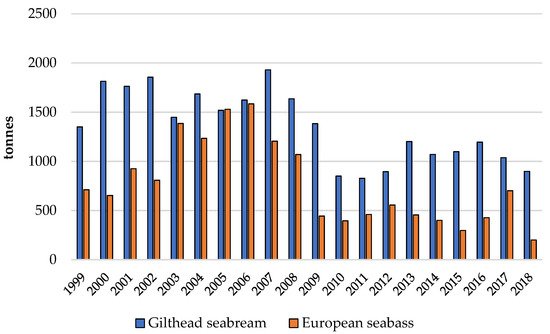

[15]; since 2010, it has been the second most cultured species in the country, and the most cultured in coastal aquaculture. European seabass is one of the most appreciated fish species in Portugal and is essentially cultured in semi-intensive systems, usually in polycultures with gilthead seabream as mentioned above, being the third most cultured fish species in Portugal. The production numbers of both species over the years are represented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Total aquaculture production of the two main marine fish species cultured in brackish and marine waters in Portugal during the period from 1999 to 2018. Data sources: INE 2000; INE 2002–2019.

Semi-intensive aquaculture productions include a certain “natural” factor in the production and development of the organisms, as they are, although in captivity, still subjected to water conditions fluctuations or natural feed entering the tanks, which play a role in the fish quality and results in differences depending on the rearing origin. For instance, fish rearing cycles’ durations differ according to the geographical site: water temperature is generally lower in the central regions of the country when compared to southern farms, with harvesting cycles taking longer at the centre of continental Portugal. These last for approximately 24 to 26 months (from the juvenile stage, about 10 g, to the marketable size), whereas, in the southern regions, cycles may take about 14 to 20 months to be completed

[18]. In semi-intensive systems, the quality of the estuarine water used is one of the most pressing parameters to be taken into account by the farmer, as well as the nutrient control, given that fish do not feed only on the food given by the farmer but also on organisms and other organic matter brought into the rearing tanks by the river flow and ocean tides. Therefore, these parameters must be carefully watched to avoid the loss of high densities of fish. Nonetheless, feeding on natural prey varies the nutritional profile of these fish, which may come as an advantage for the consumer.

Extensive production of fish is, at present, neglectable, with no records of the volume of production in such regimes. This kind of fish rearing was practiced essentially in inactive salt works, beginning, probably, when the salt market started to struggle with some difficulties

[18]. This rearing system is not as productive for fish as semi-intensive or intensive systems as only very low densities of individuals can be achieved.

2.3.2. Mollusc Production in Transitional Systems

Bivalve molluscs represent a little over 67% of the total aquaculture production in Portugal

[32]. The most produced species is the clam (

Ruditapes decussatus, Linnaeus 1758), accounting for about 42.2% of the total mollusc production, followed by mussels (

Mytilus spp.) and oysters (combined production of Portuguese oyster

Crassostrea angulata Lamarck, 1819, European flat oyster

Ostrea edulis Linnaeus, 1758 and Pacific cupped oyster

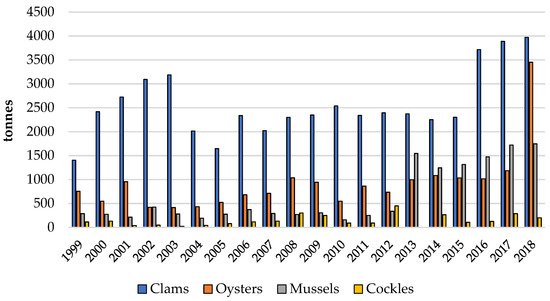

Magallana gigas Thunberg, 1793). The production of the main mollusc species produced in the time frame issued is represented in

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Total aquaculture production in transitional waters of the four main cultured mollusc species in Portugal during the period from 1999 to 2018. Data sources: INE 2000; INE 2002–2020.

The production of molluscs in continental Portugal is mainly carried out in extensive systems, although there is mollusc production in semi-intensive systems as well. Extensive rearing of molluscs is essentially carried out in parks, in their natural substrate (mud or sand)

[18] or in ropes (mainly for mussels production).

The production of molluscs in semi-intensive systems occurred occasionally over the time frame issued but in quite low quantities. The most expressive production in such systems was the production of Pacific cupped oyster in 2006 with 250 tonnes produced, and the production of 125 tonnes in 2014; clams also registered a considerable production of 88.8 tonnes in 2006 and 63.4 tonnes in 2010. However, for the remaining time, mollusc production in semi-intensive systems was nearly imperceptible

[4][5][6][7]. Clam is the main reared mollusc species in Portugal in brackish waters and the main produced species in the country. Clams are reared in parks in intertidal zones

[5], in extensive systems, essentially in the south of continental Portugal. Clam production grew continuously from 1999 to 2003, with the highest growth registered between 1999 and 2000, where a production of around 1404 tonnes in 1999 rose to a production of 2417 tonnes in the following year. The production of these organisms peaked in 2003, with 3186 tonnes produced, but dropped in following years, almost matching the production values of the year 1999. Clam production remained, until 2015, rather regular, with a rough average of a little more than 2300 tonnes produced each year. The production of these organisms recovered in 2016, presenting a rising trend ever since, as can be seen in

Figure 4 [4][5][6][7].

The production of mussels remained discrete from 1999 to 2012, revealing a peak from 338 tonnes in 2012 to 1.5 thousand tonnes in 2013, maintaining the same production amount in 2016, being the second most produced mollusc in Portugal. Although most of the aquaculture of mussels in Portugal uses long lines, in extensive systems, there was some production in intensive systems in 2009 (30 tonnes) and in 2011 (62.5 tonnes)

[4][5][6][7].

By the end of the 19th century, the Portuguese oyster was the most appreciated delicacy demanded by the European market (especially France), which led to an increase in the species’ capture in the Tagus estuary during that period, reaching, during the 1930s, exportations of 13 thousand tonnes per year

[18]. It was the only oyster species being reared in continental Portugal until 2004 when its production dropped abruptly and was replaced by the production of the Pacific oyster. The Portuguese oyster production recovered in 2009 and has been growing ever since

[4][5][6][7]. Oysters are usually reared in net bags placed on the substrate, which may subject them to predation; the culture in long lines and floating devices, used mainly in Algarve, protects animals against non-swimming predators, as the organisms are suspended in the water column

[18].

The cockle’s,

Cerastoderma edule, Linnaeus 1758, production has fluctuated during the time frame issued, maintaining a low production between 2001 and 2005, rising in 2006 and reaching a production of about 300 tonnes in 2008, the second biggest production of cockle in the period covered by the present work. The greatest production of cockle until the present time was reached in 2012, accounting for 449.2 tonnes produced. However, there was no production of this species in 2013. Since then, the production of the species has been quite unstable. Cockle production is carried out essentially in parks, using extensive systems

[4][5][6][7][18].

Portuguese aquaculture products have for a long time been introduced in national markets; however, due to market choices in importing high quantities of seafood, which are also produced in Portugal, from other major producing countries, such as Greece and Turkey, as above mentioned, this imbalanced somewhat the local products’ flow. It was only recently that a more serious effort was taken to stimulate the purchase of locally farmed fish, which has also impacted the choices of large commercial centres in terms of the products offered to consumers. Moreover, the overarching stress on social responsibility towards more sustainable consumption has also helped to push consumption of locally produced goods.

It is worth mentioning, however, that seafood in Portugal is commonly expensive for the population on the minimum and average wage (which make up most of the Portuguese population)

[20][36]. This raises a question on the ability of the Portuguese population to access healthy food environments and local production flow, as many people end up having to opt for cheaper, imported seafood. The price of Portuguese farmed seafood in coastal systems using semi-intensive and extensive systems is presented in

Table 1. This table includes values from 2018 and 2019, as more recent data are easily accessible when it comes to market values.

Table 1. Average national prices (EUR/kg) of Portuguese coastal systems’ aquaculture products for human consumption in 2018 and 2019.

| |

|

Value |

| |

Product |

2018 |

2019 |

| Fish |

Meagre |

11.12 |

5.67 |

| Gilthead seabream |

5.85 |

5.43 |

| European seabass |

8.81 |

7.31 |

| Sole |

12.85 |

11.02 |

| Eel |

6.00 |

9.00 |

| Molluscs |

Clams |

12.88 |

18.71 |

| Cockles |

0.52 |

1.05 |

| Mussels |

0.77 |

0.74 |

| Oysters |

4.26 |

10.65 |

2.4. Portuguese Aquaculture Products’ Market—Exportations and Main Consumers Worldwide

Due to the lack of available information, a comprehensive overview of the exact countries to which Portuguese farmed products are exported to was not possible. Rather, fish export information related to the destination is provided as the sum of capture and farmed goods. Major exportation destinations include Spain, Italy and France in Europe and the United States of America outside Europe

[14][37].

Nonetheless, information on the volume and value of exports of aquaculture products per se are available, accounting, in 2018, for a total of 2967 tonnes, valuing over 23 million euros. Marine species were the most exported, corresponding almost entirely to turbot (2640 tonnes), valuing 21.4 million euros; bivalve exports corresponded to only 213 tonnes, valuing 612 thousand euros, consisting mainly of oysters and mussels

[38].

The availability of detailed information regarding Portuguese aquaculture products’ exports via the institutions responsible for those records could be interesting for a further characterization of the development of the aquaculture sector in Portugal.