Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Physiology

Life on earth has evolved under the influence of rhythmic changes in the environment, such as the 24 h light/dark cycle. Living organisms have developed internal circadian clocks, which allow them to anticipate these rhythmic changes and adapt their behavior and physiology accordingly.

- suprachiasmatic nucleus

- entrainment

- masking

- chronodisruption

- molecular clockwork

- sleep deprivation

- glucocorticoids

- clock genes

1. Introduction

Life on earth has evolved under the influence of rhythmic changes in the environment, such as the 24 h light/dark cycle. Living organisms have developed internal circadian clocks, which allow them to anticipate these rhythmic changes and adapt their behavior and physiology accordingly. This is most obvious for plants in which the anticipation of the time window for photosynthesis, the light phase, provides a selection advantage over plants that simply react to the onset of the light phase. Moreover, for the early cold-blooded terrestrial animals, anticipating the light phase and, thus, the time with higher ambient temperature and better availability of visual cues has been a selection advantage. In contrast, for the early (warm-blooded) mammals, which developed in the Mesozoic (about 250 million years ago), anticipating the twilight and the dark phase, thus the time window for avoiding the diurnal predatory dinosaurs was crucial. Presumably, the early mammals gradually extended their behavior from the nocturnal towards the twilight phases of the day, resulting in activation of both cone- and rod-based vision [1]. Consequently, the neocortex, a brain region characteristic for mammals, which is responsible for higher-order brain functions, such as sensory perception, cognition, as well as the planning, control, and execution of voluntary movement, initially developed in nocturnal/crepuscular species. Only in the Cenozoic, when many species, including the non-avian dinosaurs, became extinct, mammals were released from this predatory pressure and diurnality developed among mammals [2].

2. The Role of Light and the Circadian Clock for Rhythmic Brain Function

2.1. The Mammalian Circadian System

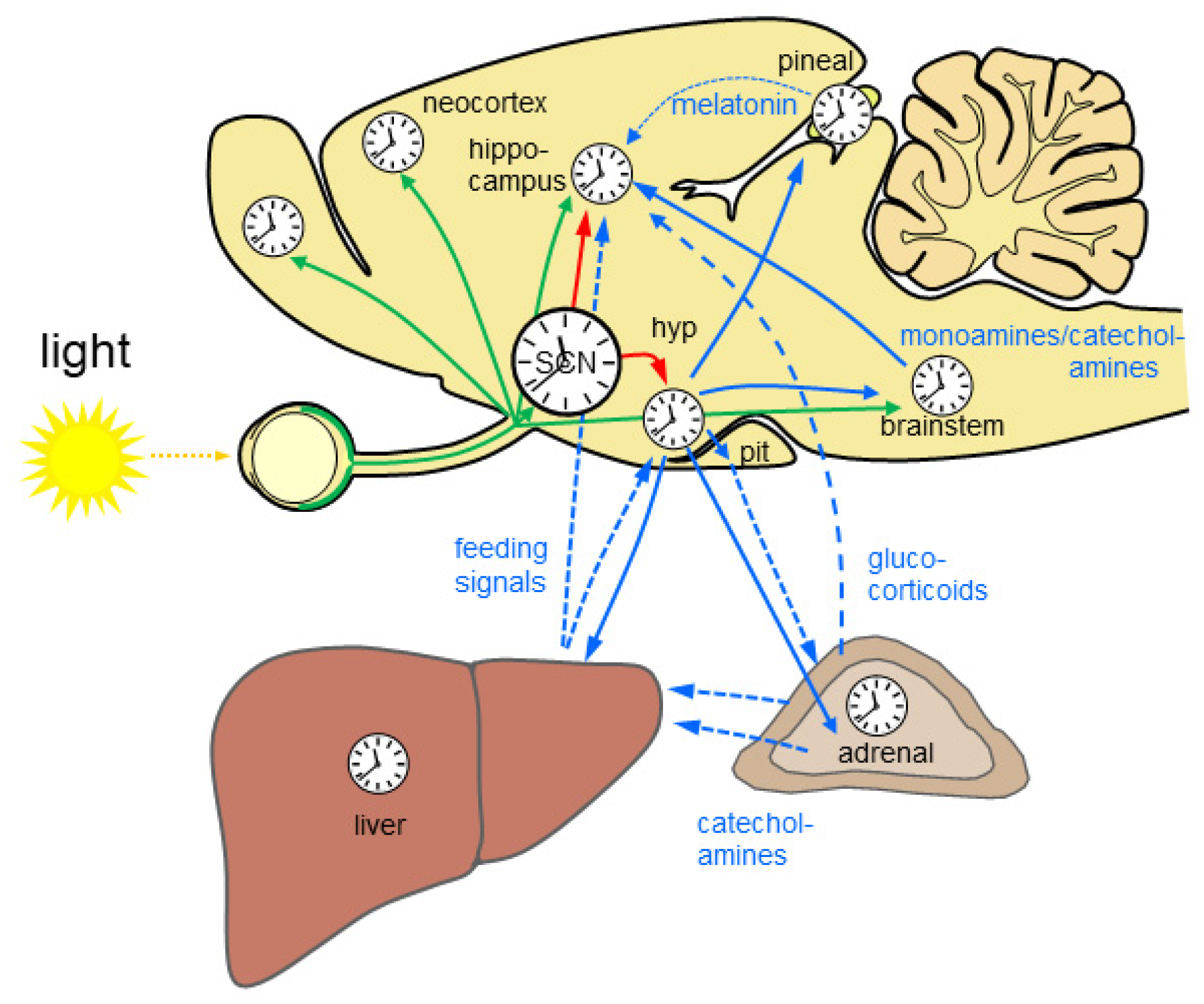

In mammals, the circadian clock is hierarchically organized in a circadian system. The central circadian rhythm generator is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. Rhythmic output of the SCN governs subsidiary circadian oscillators in the brain and the periphery. The SCN and the subsidiary oscillators consist of more or less strongly coupled cellular oscillators, each comprising a molecular clockwork composed of transcriptional/translational feedback loops of clock genes (reviewed in [3]). The SCN controls subsidiary circadian oscillators in the brain primarily via neuronal connections while peripheral oscillators are regulated via the rhythmic function of the autonomous nervous system [4] and the endocrine system [5]. The hormone of darkness, melatonin, and the stress hormone glucocorticoid [6] (see below) are important rhythmic signals for subsidiary circadian oscillators in the brain and in the periphery. The light input into the circadian system is provided by a subset of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs). There is increasing evidence that rhythmic light information is not only provided to the SCN but also directly or indirectly to many other brain regions, thus driving time-of day-dependent rhythmic brain function (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The mammalian circadian system is highly complex and hierarchically organized. Almost all brain regions and organs comprise a molecular clockwork (clocks) which controls rhythmic cell function. Rhythmic light information is provided directly and indirectly to many brain regions (green arrows) and drives time-of-day-dependent rhythms in brain and periphery. The central circadian rhythm generator which is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus is entrained by light. SCN lesion results in loss of circadian rhythms. Rhythmic output of the SCN governs subsidiary circadian oscillators in the brain (red arrows). Different nuclei in the hypothalamus (hyp) control rhythmic physiology and behavior via neuronal connections including the autonomous nervous system (blue solid arrows) and endocrine signals (blue dashed arrows) via the pituitary (pit). Rhythmic endocrine signal from the pineal gland and the periphery (blue dashed lines) provide additional rhythmic signals for the brain. The liver is depicted exemplarily for the gastrointestinal system. Monoamines and catecholamines from the brain stem provide important rhythmic drive for alertness and motivation at the level of the forebrain. Based on [7][8][9].

Figure 1. The mammalian circadian system is highly complex and hierarchically organized. Almost all brain regions and organs comprise a molecular clockwork (clocks) which controls rhythmic cell function. Rhythmic light information is provided directly and indirectly to many brain regions (green arrows) and drives time-of-day-dependent rhythms in brain and periphery. The central circadian rhythm generator which is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus is entrained by light. SCN lesion results in loss of circadian rhythms. Rhythmic output of the SCN governs subsidiary circadian oscillators in the brain (red arrows). Different nuclei in the hypothalamus (hyp) control rhythmic physiology and behavior via neuronal connections including the autonomous nervous system (blue solid arrows) and endocrine signals (blue dashed arrows) via the pituitary (pit). Rhythmic endocrine signal from the pineal gland and the periphery (blue dashed lines) provide additional rhythmic signals for the brain. The liver is depicted exemplarily for the gastrointestinal system. Monoamines and catecholamines from the brain stem provide important rhythmic drive for alertness and motivation at the level of the forebrain. Based on [7][8][9].2.2. Light Input into the Circadian System—Entrainment and Masking

Two main mechanisms help to specialize in a nocturnal or a diurnal niche [10]. In the mechanism called entrainment, light serves as a signal for the SCN, to match the period and the phase to the environmental oscillator, the light/dark regime. Adjusting the period is necessary, as the endogenous rhythm, persisting in constant darkness, is close to but not exact 24 h. The SCN in turn helps to anticipate the rhythmic changes in the environment and controls activity during the dark or the light phase. This is important, as many nocturnal mammals live in dark burrows and experience the environmental light conditions only when leaving the safe surrounding of the nest. Entrainment is adaptive, as the lengths of the light and dark phase change according to the seasons, depending on the latitude. In the mechanism called masking, light directly affects behavior obscuring the control from the circadian clock [11]. Masking is especially prominent in nocturnal species, and, here, light can have two opposite effects on activity depending on irradiance levels. In dim light, activity is increased compared to complete darkness. This enhancing effect of dim light, which is presumably due to increased confidence based on visual input [12], is called positive masking [10]. However, in complete darkness, activity is higher, despite the absence of visual cues, than under standard (bright) light conditions. This suppressive effect of bright light on activity is called negative masking [10]. Similarly, nocturnal animals prefer dark or dimly illuminated areas over brightly illuminated areas. This light aversion is strong enough to counteract the natural tendency to explore a novel environment, as shown by the light–dark test [13], a paradigm extensively used for tests on classic anxiolytics (benzodiazepines) [13], as well as anxiolytic-like compounds, such as serotonergic drugs or drugs acting on neuropeptide receptors (reviewed in [14]). In both diurnal and nocturnal mammals, light at night also elicits acute effects on physiological parameters, such as core body temperature and heart rate, as well as hormone secretion (see below). Importantly, the detection of visual information in the mammalian retina is conveyed by two parallel pathways, the rod–cone system for image-forming-vision and the melanopsin-based system of the ipRGCs for non-image-forming irradiance detection. Although ipRGCs are essential for the adaptive physiological responses to light, such as the pupillary light reflex [15], as well as circadian entrainment [16][17], and contribute to scotopic vision [18], both the rod–cone system and the ipRGCs seem to contribute to masking and light aversion [19]. Importantly, many commonly used laboratory mouse strains carry mutations that affect visual and/or non-visual physiology (reviewed in [20]).

Under natural conditions, entrainment and masking work in a complementary fashion [21]. However, in the laboratory, the two mechanisms can be segregated. As mentioned above, entrainment is highly adaptive to different photoperiods. In most animal facilities, the standard photoperiod is 12 h light and 12 h dark (LD 12:12), although some animal facilities have opted for different light conditions (e.g., LD 16:8), as the photoperiod has a high impact on reproduction in some species. The circadian clock also rapidly entrains to a phase shift one experiences when travelling across time zones or if the LD cycle is inverted. The re-entrainment capacity after jet lag is dependent on intrinsic factors, such as the robustness of the circadian clock or the signaling of hormones, such as melatonin [22]. Furthermore, the speed of re-entrainment to a phase shift depends on the direction; entrainment is usually faster in response to a phase delay than a phase advance [23]. Interestingly, this is the same in the diurnal human [24]. However, in nocturnal animals, brief light pulses during the early and late night are strong resetting cues for phase delays and advances of the circadian clock, respectively [25]. At the cellular level, photic resetting of the SCN molecular clockwork involves activation of the p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade, phosphorylation/activation of the transcription factor cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB) [26], the induction of the marker of neuronal activity c-Fos [27], inhibitors of DNA binding proteins [28], and expression of the clock gene Per1 [29]. In order to study entrainment in the absence of the interfering masking effects of light, nocturnal animals can be housed under a so-called skeleton photoperiod, consisting of two discrete pulses of light during the early (dawn) and the late (dusk) light phase [30]. For entrainment to this lighting schedule, the intergeniculate leaflet is essential, which receives direct photic information from the ipRGCs [31].

2.3. The Brain Molecular Clockwork

Various brain functions, such as sleep, wake, foraging, food intake, alertness, emotion, motivation, and cognitive performance, controlled by different brain regions, show circadian rhythms. Moreover, any information is processed in a temporal context. Consistently, many brain regions harbour circadian oscillators, which are governed by the SCN [32]. At the cellular level, these oscillators are composed of single cells each harbouring a molecular clockwork composed of transcriptional/translational feedback loops of clock genes. The clock genes encode for activators of transcription, such as CLOCK and its forebrain-specific analog NPAS2 [33], BMAL1, and ROR, as well as the repressors of transcription PER1 and PER2, CRY1, CRY2, and REV-ERBα [3].

The molecular clockwork drives the rhythmic expression of clock controlled gene (see below) and posttranscriptional processes (reviewed in [34]) and modulates the chromatin landscape [35], thus regulating rhythmic cell function at multiple levels. The molecular clockwork in the SCN and subordinate extra-SCN brain circadian oscillators drives various rhythms in neuron and glia function including ATP concentration [36], neuronal electrical activity (reviewed in [37]), metabolism [38], redox homeostasis (reviewed in [39]), tyrosine hydroxylase expression in dopaminergic neurons [40], dopamine receptor signalling in the hippocampus [41], and extracellular glutamate homeostasis [42]. In addition, some rhythms in the SCN are time-of day-dependent and do not persist in constant darkness, such as rhythmic expression of connexion 30 [43], which contribute to astrocyte gap junctions and hemichannels (reviewed in [44]), as well as the stability of circadian rhythms and re-entrainment under challenging conditions [43]. Circadian clock gene expression in the SCN and the hippocampus persists with high robustness in vitro, indicating a strong coupling of single cell oscillators, while it damps rapidly in other brain regions, indicating a weak coupling [45][46][47]. Mice with a targeted deletion of the essential clock gene Bmal1 are arrhythmic under constant environmental conditions [48], so a loss of function in a single gene strongly affects circadian rhythmicity. In mouse models for compromised molecular clockwork function, such as Bmal1-deficient mice, Per1/2 double mutants, and Cry1/Cry2 double mutants, circadian rhythms are abolished, while various parameters of physiology and behaviour are rhythmic under the LD 12:12 conditions due to masking [48][49][50]. This emphasizes the strong impact of the environmental light/dark conditions on rhythmic brain function. In this context, it is important to note that Cry1/Cry2 double mutants and Bmal1-deficient mice show deficits in retinal visual physiology [51] and, consequently, impaired visual input into the circadian system [52][53]. Nevertheless, even under LD 12:12 conditions, many brain functions, such as spatial memory consolidation and contextual fear [54][55], adult neurogenesis [56], and sleep architecture [57] are affected in Bmal1-deficient mice, indicating the importance of this clock gene/transcription factor for general brain function.

2.4. Rhythmic Gene and Protein Expression in the Brain

About 43% of all coding genes and about 1000 noncoding RNAs show circadian rhythms in transcription somewhere in the body, largely in an organ/tissue-specific manner [58][59][60]. The rhythmic transcriptome in peripheral organs is dependent on the SCN [60] but continues to oscillate in vitro for a few cycles [61]. Only 22% of circadian rhythmic mRNA is driven by de novo transcription, indicating that the molecular clock drives transcription and posttranslational modification [35]. Moreover, the epigenetic landscape is modulated in a circadian manner [35]. A comparable number of transcripts show a circadian oscillation in the SCN and the liver, while only about 10% of them show an overlap [59]. The core clock genes Arntl (encoding for Bmal1), Dbp, Nr1d1 and Nr1d2 (encoding for Rev-Erb alpha and beta, respectively), Per1, Per2, and Per3, as well as the clock controlled genes Usp2, Tsc22d3, and Tspan4 oscillate in many organs and parts of the brain [58]. Importantly, many commonly used drugs target the products of the circadian genes, so the timed application of these drugs, chronotherapy, might maximize efficacy, and minimize side effects [58]. In accordance with the important role of the brain stem in the regulation of autonomous and vital functions, more than 30% of the drug-target circadian genes listed in the study by Zhang et al. (2014) are rhythmically expressed in this part of the brain. In the retina, about 277 genes show a circadian rhythm, implicated in a variety of functions, including synaptic transmission, photoreceptor signalling, intracellular communication, cytoskeleton reorganization, and chromatin remodelling [62]. Intriguingly, in LD 12:12, about 10 times as many genes oscillate, indicating that the LD cycle drives the rhythmic expression of a large number of genes in the retina [62]. In the forebrain synapses, a comparable amount of genes (2085, thus 67% of synaptic RNAs) show a time-of-day-dependent rhythm, and a high percentage of these genes remain rhythmic in constant darkness (circadian) [63]. Interestingly, the rhythmic genes in the forebrain synapses can be segregated into two temporal domains, predusk and predawn, relating to distinct functions; predusk mRNAs relate to synapse organization, synaptic transmission, cognition, and behaviour, while predawn mRNAs relate to metabolism, translation, and cell proliferation or development [63]. The oscillation of the synaptic proteome resembles those of the transcriptome [63] and a high percentage show an oscillation in the phosphorylation state [64].

2.5 Sleep Deprivation, Epilepsy, and Glucocorticoids Affect Gene and Protein Expression in the Brain

Sleep deprivation induced by gentle handling, cage tapping, and the introduction of novel objects during the light/inactive phase affects clock gene expression in the cerebral cortex [65] and leads to a reduction in transcript oscillation in the entire brain to about 20% [66]. This indicates that the sleep disruption itself, and/or the manipulation, as well as the associated additional light exposure, which mice usually do not experience while sleeping, strongly affects rhythmic transcription. On the other hand, it shows that only 20% of the rhythmic transcriptome in the brain is resilient to sleep deprivation, manipulation, and light exposure during the light/inactive phase. In forebrain synapses, sleep deprivation has a higher impact on the proteome and on rhythmic protein phosphorylation than on the transcriptome [63][64]. In this context, it is important to note that traditional sleep deprivation protocols using sensory-motor stimulation induces stress associated with a rise in circulating corticosterone [67], an important temporal signal within the circadian system. Corticosterone strongly contributes to the sleep-deprivation-induced forebrain transcriptome [68]. Among the genes assigned to the corticosterone surge are clock genes, as well as genes implicated in sleep homeostasis, cell metabolism, and protein synthesis, while the transcripts that respond to sleep loss independent of corticosterone relate to neuroprotection [68]. The time-of-day-dependent oscillation in hippocampal transcriptome and proteome is affected by temporal lobe epilepsy [69]. Although epilepsy could be considered a chronic stress model [70], little is known on the contribution of glucocorticoids in these alterations. More research avoiding stress as a confounder is needed to explore the effect of sleep and neurological disorders on rhythmic brain function.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23052778

References

- Davies, W.I.L.; Collin, S.P.; Hunt, D.M. Molecular ecology and adaptation of visual photopigments in craniates. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 3121–3158.

- Maor, R.; Dayan, T.; Ferguson-Gow, H.; Jones, K.E. Temporal niche expansion in mammals from a nocturnal ancestor after dinosaur extinction. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1889–1895.

- Reppert, S.M.; Weaver, D.R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 2002, 418, 935–941.

- Buijs, R.M.; La Fleur, S.E.; Wortel, J.; Van Heyningen, C.; Zuiddam, L.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Kalsbeek, A.; Nagai, K.; Niijima, A. The suprachiasmatic nucleus balances sympathetic and parasympathetic output to peripheral organs through separate preautonomic neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 464, 36–48.

- Kalsbeek, A.; Palm, I.F.; La Fleur, S.E.; Scheer, F.; Perreau-Lenz, S.; Ruiter, M.; Kreier, F.; Cailotto, C.; Buijs, R.M. SCN Outputs and the Hypothalamic Balance of Life. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2006, 21, 458–469.

- Balsalobre, A.; Brown, S.A.; Marcacci, L.; Tronche, F.; Kellendonk, C.; Reichardt, H.M.; Schütz, G.; Schibler, U. Resetting of Circadian Time in Peripheral Tissues by Glucocorticoid Signaling. Science 2000, 289, 2344–2347.

- Pasquier, D.A.; Reinoso-Suarez, F. The topographic organization of hypothalamic and brain stem projections to the hippocampus. Brain Res. Bull. 1978, 3, 373–389.

- Korf, H.-W.; von Gall, C. Circadian Physiology. In Neuroscience in the 21st Century; Pfaff, D.W., Volkow, N.D., Eds.; Springer Science+Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016.

- Fernandez, D.C.; Fogerson, P.M.; Ospri, L.L.; Thomsen, M.B.; Layne, R.M.; Severin, D.; Zhan, J.; Singer, J.H.; Kirkwood, A.; Zhao, H.; et al. Light Affects Mood and Learning through Distinct Retina-Brain Pathways. Cell 2018, 175, 71–84.e18.

- Mrosovsky, N. Masking: History, Definitions, and Measurement. Chronol. Int. 1999, 16, 415–429.

- Aschoff, J. Exogenous and Endogenous Components in Circadian Rhythms. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1960, 25, 11–28.

- Thompson, S.; Philp, A.R.; Stone, E.M. Visual function testing: A quantifiable visually guided behavior in mice. Vis. Res. 2008, 48, 346–352.

- Crawley, J.; Goodwin, F.K. Preliminary report of a simple animal behavior model for the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1980, 13, 167–170.

- Bourin, M.; Hascoët, M. The mouse light/dark box test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 463, 55–65.

- Lucas, R.J.; Hattar, S.; Takao, M.; Berson, D.M.; Foster, R.G.; Yau, K.-W. Diminished Pupillary Light Reflex at High Irradiances in Melanopsin-Knockout Mice. Science 2003, 299, 245–247.

- Panda, S.; Sato, T.K.; Castrucci, A.M.; Rollag, M.D.; DeGrip, W.J.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Provencio, I.; Kay, S.A. Melanopsin (Opn4) Requirement for Normal Light-Induced Circadian Phase Shifting. Science 2002, 298, 2213–2216.

- Ruby, N.F.; Brennan, T.J.; Xie, X.; Cao, V.; Franken, P.; Heller, H.C.; O’Hara, B.F. Role of Melanopsin in Circadian Responses to Light. Science 2002, 298, 2211–2213.

- Ecker, J.L.; Dumitrescu, O.N.; Wong, K.; Alam, N.M.; Chen, S.-K.; LeGates, T.; Renna, J.M.; Prusky, G.T.; Berson, D.M.; Hattar, S. Melanopsin-Expressing Retinal Ganglion-Cell Photoreceptors: Cellular Diversity and Role in Pattern Vision. Neuron 2010, 67, 49–60.

- Hattar, S.; Lucas, R.J.; Mrosovsky, N.; Thompson, S.; Douglas, R.H.; Hankins, M.W.; Lem, J.; Biel, M.; Hofmann, F.; Foster, R.G.; et al. Melanopsin and rod–cone photoreceptive systems account for all major accessory visual functions in mice. Nature 2003, 424, 75–81.

- Peirson, S.N.; Brown, L.; Pothecary, C.A.; Benson, L.A.; Fisk, A.S. Light and the laboratory mouse. J. Neurosci. Methods 2018, 300, 26–36.

- Aschoff, J.; Von Goetz, C. Masking of circadian activity rhythms in hamsters by darkness. J. Comp. Physiol. A Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 1988, 162, 559–562.

- Pfeffer, M.; Rauch, A.; Korf, H.; Von Gall, C. The Endogenous Melatonin (MT) Signal Facilitates Reentrainment of the Circadian System to Light-Induced Phase Advances by Acting Upon MT2 Receptors. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 415–429.

- Reddy, A.B.; Field, M.D.; Maywood, E.S.; Hastings, M.H. Differential Resynchronisation of Circadian Clock Gene Expression within the Suprachiasmatic Nuclei of Mice Subjected to Experimental Jet Lag. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 7326–7330.

- Wever, R.A. Phase shifts of human circadian rhythms due to shifts of artificial Zeitgebers. Chronobiologia 1980, 7, 303–327.

- Gillette, M.U.; Mitchell, J.W. Signaling in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: Selectively responsive and integrative. Cell Tissue Res. 2002, 309, 99–107.

- Ginty, D.D.; Kornhauser, J.M.; Thompson, M.A.; Bading, H.; Mayo, K.E.; Takahashi, J.S.; Greenberg, M.E. Regulation of CREB Phosphorylation in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus by Light and a Circadian Clock. Science 1993, 260, 238–241.

- Zhang, Y.; Kornhauser, J.; Zee, P.; Mayo, K.; Takahashi, J.; Turek, F. Effects of aging on light-induced phase-shifting of circadian behavioral rhythms, Fos expression and creb phosphorylation in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 1996, 70, 951–961.

- Duffield, G.E.; Robles-Murguia, M.; Hou, T.Y.; McDonald, K.A. Targeted Disruption of the Inhibitor of DNA Binding 4 (Id4) Gene Alters Photic Entrainment of the Circadian Clock. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9632.

- Gau, D.; Lemberger, T.; von Gall, C.; Kretz, O.; Le Minh, N.; Gass, P.; Schmid, W.; Schibler, U.; Korf, H.; Schütz, G. Phosphorylation of CREB Ser142 Regulates Light-Induced Phase Shifts of the Circadian Clock. Neuron 2002, 34, 245–253.

- Pittendrigh, C.S.; Daan, S. A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. J. Comp. Physiol. 1976, 106, 223–252.

- Edelstein, K.; Amir, S. The Role of the Intergeniculate Leaflet in Entrainment of Circadian Rhythms to a Skeleton Photoperiod. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 372–380.

- Inouye, S.T.; Kawamura, H. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in a mammalian hypothalamic “island” containing the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 5962–5966.

- Reick, M.; Garcia, J.A.; Dudley, C.; McKnight, S.L. NPAS2: An Analog of Clock Operative in the Mammalian Forebrain. Science 2001, 293, 506–509.

- Green, C.B. Circadian Posttranscriptional Regulatory Mechanisms in Mammals. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a030692.

- Koike, N.; Yoo, S.-H.; Huang, H.-C.; Kumar, V.; Lee, C.; Kim, T.-K.; Takahashi, J.S. Transcriptional Architecture and Chromatin Landscape of the Core Circadian Clock in Mammals. Science 2012, 338, 349–354.

- Yamazaki, S.; Ishida, Y.; Inouye, S.-I.T. Circadian rhythms of adenosine triphosphate contents in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, anterior hypothalamic area and caudate putamen of the rat—Negative correlation with electrical activity. Brain Res. 1994, 664, 237–240.

- Colwell, C.S. Linking neural activity and molecular oscillations in the SCN. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 553–569.

- Schwartz, W.J.; Gainer, H. Suprachiasmatic Nucleus: Use of 14 C-Labeled Deoxyglucose Uptake as a Functional Marker. Science 1977, 197, 1089–1091.

- Musiek, E.; Lim, M.M.; Yang, G.; Bauer, A.Q.; Qi, L.; Lee, Y.; Roh, J.H.; Ortiz-Gonzalez, X.; Dearborn, J.; Culver, J.P.; et al. Circadian clock proteins regulate neuronal redox homeostasis and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 5389–5400.

- Chung, S.; Lee, E.J.; Yun, S.; Choe, H.K.; Park, S.B.; Son, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Dluzen, D.E.; Lee, I.; Hwang, O.; et al. Impact of circadian nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha on midbrain dopamine production and mood regulation. Cell 2014, 157, 858–868.

- Hasegawa, S.; Fukushima, H.; Hosoda, H.; Serita, T.; Ishikawa, R.; Rokukawa, T.; Kawahara-Miki, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ohta, M.; Okada, S.; et al. Hippocampal clock regulates memory retrieval via Dopamine and PKA-induced GluA1 phosphorylation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14.

- Brancaccio, M.; Patton, A.; Chesham, J.E.; Maywood, E.S.; Hastings, M.H. Astrocytes Control Circadian Timekeeping in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus via Glutamatergic Signaling. Neuron 2017, 93, 1420–1435.e5.

- Ali, A.A.H.; Stahr, A.; Ingenwerth, M.; Theis, M.; Steinhäuser, C.; Von Gall, C. Connexin30 and Connexin43 show a time-of-day dependent expression in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus and modulate rhythmic locomotor activity in the context of chronodisruption. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 61.

- Xing, L.; Yang, T.; Cui, S.; Chen, G. Connexin Hemichannels in Astrocytes: Role in CNS Disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 23.

- Abe, M.; Herzog, E.D.; Yamazaki, S.; Straume, M.; Tei, H.; Sakaki, Y.; Menaker, M.; Block, G.D. Circadian Rhythms in Isolated Brain Regions. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 350–356.

- Wang, L.M.-C.; Dragich, J.M.; Kudo, T.; Odom, I.H.; Welsh, D.K.; O’Dell, T.J.; Colwell, C.S. Expression of the Circadian Clock Gene Period2 in the Hippocampus: Possible Implications for Synaptic Plasticity and Learned Behaviour. ASN Neuro 2009, 1, AN20090020.

- Schmal, C.; Herzog, E.D.; Herzel, H. Measuring Relative Coupling Strength in Circadian Systems. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2018, 33, 84–98.

- Bunger, M.K.; Wilsbacher, L.D.; Moran, S.M.; Clendenin, C.; Radcliffe, L.A.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Simon, M.C.; Takahashi, J.S.; Bradfield, C.A. Mop3 Is an Essential Component of the Master Circadian Pacemaker in Mammals. Cell 2000, 103, 1009–1017.

- Van Der Horst, G.T.J.; Muijtjens, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Takano, R.; Kanno, S.-I.; Takao, M.; De Wit, J.; Verkerk, A.; Eker, A.P.M.; Van Leenen, D.; et al. Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature 1999, 398, 627–630.

- Van Gelder, R.N.; Gibler, T.M.; Tu, D.; Embry, K.; Selby, C.P.; Thompson, C.L.; Sancar, A. Pleiotropic effects of cryptochromes 1 and 2 on free-running and light-entrained murine circadian rhythms. J. Neurogenet. 2002, 16, 181–203.

- Selby, C.P.; Thompson, C.; Schmitz, T.M.; Van Gelder, R.; Sancar, A. Functional redundancy of cryptochromes and classical photoreceptors for nonvisual ocular photoreception in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 14697–14702.

- Pfeffer, M.; Müller, C.M.; Mordel, J.; Meissl, H.; Ansari, N.; Deller, T.; Korf, H.-W.; Von Gall, C. The Mammalian Molecular Clockwork Controls Rhythmic Expression of Its Own Input Pathway Components. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 6114–6123.

- Öztürk, M.; Ingenwerth, M.; Sager, M.; von Gall, C.; Ali, A. Does a Red House Affect Rhythms in Mice with a Corrupted Circadian System? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2288.

- Kondratova, A.A.; Dubrovsky, Y.V.; Antoch, M.P.; Kondratov, R.V. Circadian clock proteins control adaptation to novel environment and memory formation. Aging 2010, 2, 285–297.

- Wardlaw, S.M.; Phan, T.X.; Saraf, A.; Chen, X.; Storm, D.R. Genetic disruption of the core circadian clock impairs hippocampus-dependent memory. Learn. Mem. 2014, 21, 417–423.

- Ali, A.; Schwarz-Herzke, B.; Stahr, A.; Prozorovski, T.; Aktas, O.; Von Gall, C. Premature aging of the hippocampal neurogenic niche in adult Bmal1- deficient mice. Aging 2015, 7, 435–449.

- Laposky, A.; Easton, A.; Dugovic, C.; Walisser, J.; Bradfield, C.; Turek, F. Deletion of the mammalian circadian clock gene BMAL1/Mop3 alters baseline sleep architecture and the response to sleep deprivation. Sleep 2005, 28, 395–409.

- Zhang, R.; Lahens, N.F.; Ballance, H.I.; Hughes, M.E.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Pfeffer, M.; Maronde, E.; Bonig, H. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: Implications for biology and medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16219–16224.

- Panda, S.; Antoch, M.P.; Miller, B.H.; Su, A.I.; Schook, A.B.; Straume, M.; Schultz, P.G.; Kay, S.A.; Takahashi, J.; Hogenesch, J.B. Coordinated Transcription of Key Pathways in the Mouse by the Circadian Clock. Cell 2002, 109, 307–320.

- Akhtar, R.; Reddy, A.B.; Maywood, E.S.; Clayton, J.D.; King, V.M.; Smith, A.G.; Gant, T.; Hastings, M.H.; Kyriacou, C.P. Circadian Cycling of the Mouse Liver Transcriptome, as Revealed by cDNA Microarray, Is Driven by the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 540–550.

- Duffield, G.E.; Best, J.D.; Meurers, B.H.; Bittner, A.; Loros, J.J.; Dunlap, J.C. Circadian Programs of Transcriptional Activation, Signaling, and Protein Turnover Revealed by Microarray Analysis of Mammalian Cells. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 551–557.

- Storch, K.-F.; Paz, C.; Signorovitch, J.; Raviola, E.; Pawlyk, B.; Li, T.; Weitz, C.J. Intrinsic Circadian Clock of the Mammalian Retina: Importance for Retinal Processing of Visual Information. Cell 2007, 130, 730–741.

- Noya, S.B.; Colameo, D.; Brüning, F.; Spinnler, A.; Mircsof, D.; Opitz, L.; Mann, M.; Tyagarajan, S.K.; Robles, M.S.; Brown, S.A. The forebrain synaptic transcriptome is organized by clocks but its proteome is driven by sleep. Science 2019, 366, eaav2642.

- Brüning, F.; Noya, S.B.; Bange, T.; Koutsouli, S.; Rudolph, J.D.; Tyagarajan, S.K.; Cox, J.; Mann, M.; Brown, S.A.; Robles, M.S. Sleep-wake cycles drive daily dynamics of synaptic phosphorylation. Science 2019, 366, eaav3617.

- Wisor, J.P.; O’Hara, B.F.; Terao, A.; Selby, C.P.; Kilduff, T.S.; Sancar, A.; Edgar, D.M.; Franken, P. A role for cryptochromes in sleep regulation. BMC Neurosci. 2002, 3, 20.

- Maret, S.; Dorsaz, S.; Gurcel, L.; Pradervand, S.; Petit, B.; Pfister, C.; Hagenbuchle, O.; O’Hara, B.F.; Franken, P.; Tafti, M. Homer1a is a core brain molecular correlate of sleep loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20090–20095.

- Nollet, M.; Wisden, W.; Franks, N.P. Sleep deprivation and stress: A reciprocal relationship. Interface Focus 2020, 10, 20190092.

- Mongrain, V.; Hernandez, S.A.; Pradervand, S.; Dorsaz, S.; Curie, T.; Hagiwara, G.; Gip, P.; Heller, H.C.; Franken, P. Separating the Contribution of Glucocorticoids and Wakefulness to the Molecular and Electrophysiological Correlates of Sleep Homeostasis. Sleep 2010, 33, 1147–1157.

- Debski, K.J.; Ceglia, N.; Ghestem, A.; Ivanov, A.I.; Brancati, G.E.; Bröer, S.; Bot, A.M.; Müller, J.A.; Schoch, S.; Becker, A.; et al. The circadian dynamics of the hippocampal transcriptome and proteome is altered in experimental temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaat5979.

- Cano-López, I.; Gonzalez-Bono, E. Cortisol levels and seizures in adults with epilepsy: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 103, 216–229.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!