Nowadays, Indonesian palm oil faces agrarian, environmental, and social issues and has been subject to sharp criticism from the international community for many years. To answer this problem, the Indonesian government implemented a strategy through certification which ensured the achievement of sustainability standards, especially on the upstream side of the palm oil supply chain. The implementation of Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) was an ultimate instrument that applied in particular to smallholders oriented towards managing land legal issues, plantation business licenses, plant seeds, and environmental management and to farmer organizations at the local level. However, this process faced quite complex challenges in the form of structural barriers that are very constraining.

- governance

- ISPO

- certification

- sustainability policy

- smallholders

1. Introduction

2. The Oil Palm Governance in Indonesia

2.1. The Absence of Some Regulations to Support ISPO Policy

2.2. The Power of ISPO Policy as Institutional Driving Force

This ISPO certification has become the main key performance indicator of the Plantation Office of East Kalimantan Province especially for environmental indicators. The major economic role of oil palm in providing income and employment opportunities has put the sector particularly important for East Kalimantan Province economy. The provincial government had been therefore concerned to increase the number of ISPO-certified companies, yearly. There had been IUP (Plantation Business Permit) of 2,525,839 hectares of the total allocation of 3,269,561 hectares in spatial planning allocated for oil palm plantation area. Providing better regulations for ISPO implementation will be of importance. (Mr. UR, Head of the Plantation Office of East Kalimantan Province) (Statement conveyed in Focus Group Discussion (FGD): East Kalimantan Sustainable Oil Palm Dynamics in Indonesia ISPO Certification to Challenges in the European Market, 1 October 2020)

“In general, there is a complexity in ISPO certification implementation processes. In the case of legality issue, the government strongly urges land legality, because any non-legalized plantations bring no socio-economic benefits to the government and environment. For plantations that have not been properly legalized, of course, certification processes will burden the state budgetary if the certification program should be borne by the government. In the context of financial efficiency, I agree that the issue of sustainability must be referred to the company. This is because the government will be burdened much by the expenditure of bearing the certification costs to administer these non-legalized oil-palm-related business units. However, putting the burden on the companies makes the government to feel unpleasant. This is because, the researchers let the certification to run imperfectly. (Mr. DI, Head of Regional Development Planning Office of Jambi Province, 2021) (Idem)”.

2.3. The Effect of ISPO Policy on Local Territory

“I really appreciate the Jambi Provincial Government, and the District Government of Merangin, for providing all facilities to ISPO certification process. The Jambi government really helped the implementation of palm oil certification. For example, in processing STDB and SPPL, the researchers collaborated with the government offices. The office was amazingly fast in processing documents. The service had been designed users (smallholders) friendly. the researchers often met with friends from other regions outside Jambi complaining complexity of the process to follow. The thing that was found in Jambi Provincial Government offices was quite different from the services provided by other regional governments” (Mr. SLK, Famer Association of Tanjung Sehati, Jambi) (Statement conveyed in Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with the stakeholders of Jambi Province Sustainable Oil Palm Dynamics in Indonesia ISPO Certification to Challenges in the European Market, October 2020)

“The non-governmental organization SETARA bears the initial financing for ISPO certification processes. They prepare to give financial assistance but what about the financial support for surveillance audit in the 2nd year, 3rd year or 4th year? Who will bear the cost of surveillance? Is it possible to encourage large oil palm companies, where independent smallholders supplied their fruits, to participate bearing these costs? But the most likely to do is to encourage the involvement of the Palm Oil Plantation Fund Management Agency (Badan Pengelola Dana Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit or BPDPKS) belonging to the government of Indonesia to participate. The BPDPKS could allocate funds to help financial support for ISPO certification processes of independent smallholders in Indonesia”.

2.4. Imbalance of Multi-Level Authorities of ISPO Policy

“Supporting STDB (and other licenses administration) facilitation is not easy task for district government institutions. Several obstacles immediately appeared. The facts show that the central government delegates the facilitation of STDB management to district government authority in the regions. The administration STDB included mapping out the planted area of each single smallholder. However, this delegation of authority is not accompanied by supportive budget or financial support. Everyone knows, the location of oil palm plantations belonging to smallholders is spatially spread in the sub-district and cross-village areas. Meanwhile, the number and qualifications of human resources to do the job are limited at district government. In addition, the availability of supporting equipment (for mapping out the planted area) is limited as well. With these various limitations, it is impossible for us to optimally support the ISPO certification process. Still, the researchers witness sheer number of agrarian problems relating to plantation in the forest area (that need to be better managed). All of these jobs are beyond ability to handle”. (Mr. ABS—Plantation Office of Kutai Kartanegara District of East Kalimantan Province).

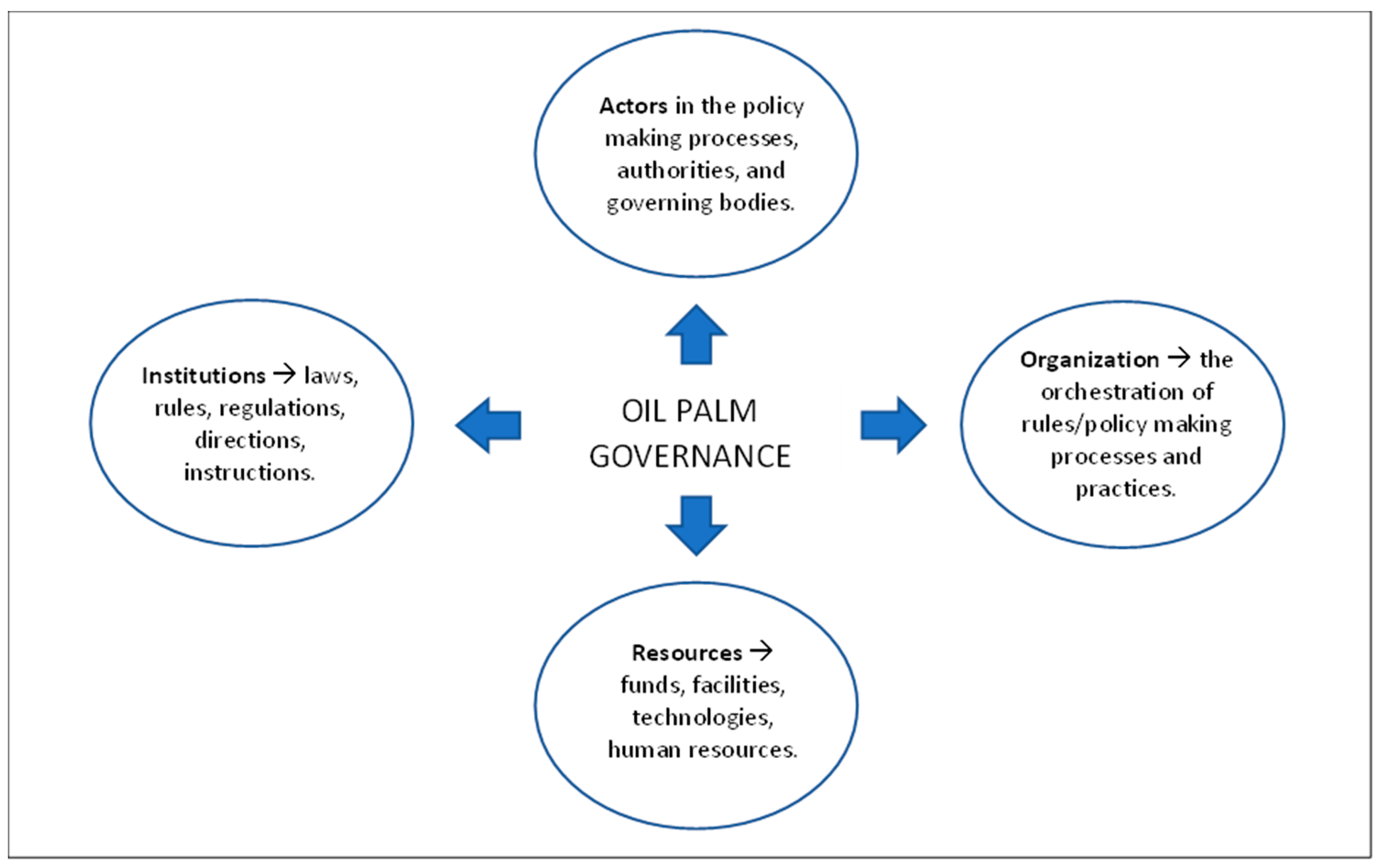

2.5. On the Theory of Low-Functioning Governance

- There was serious absence of co-ordination as well as mutual support, mutual understanding, and communication that brought about the institutional or functional disconnection among those related to the palm oil certification mission. This situation gave rise to the absence of a coherent, integrated, and mutual enforcement among the authorities, as well as the governing institutions of the regional and local governing bodies.

- There were resource weaknesses at each level of the policy-making processes and arenas along the hierarchy of the palm oil government administration. They were especially weak in terms of the technical and management capability, financial capacity, and human capital that was involved in the formulation of policy and regulation. It needs strong external assistance if the palm oil governance is to be improved.

- There was a widespread misinterpretation of the idea of sustainability and palm oil certification due to poor communication and interaction among the stakeholders that were involved in the policy-making processes and the people of the governing bodies, as well as the oil palm business actors in local/regional government.

- The stakeholders of the local/regional governance level had very little knowledge on why the oil palm plantations should follow the legality standards and sustainability procedures so strictly. On the contrary, they failed to understand how better production opportunities may result in beneficial outcomes after the ISPO certification had been made.

2.6. Mitigation Measures: The Way Forward

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14031820

References

- Aguiar, L.K.; Martinez, D.C.; Caleman, S.M.Q. Consumer Awareness of Palm Oil as an Ingredient in Food and Non-Food Products. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 24, 297–310.

- Capecchi, S.; Amato, M.; Sodano, V.; Verneau, F. Understanding beliefs and concerns towards palm oil: Empirical evidence and policy implications. Food Policy 2019, 89, 101785.

- Mayr, S.; Hollaus, B.; Madner, V. Palm oil, the RED II and WTO law: EU sustainable biofuel policy tangled up in green? Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2021, 30, 233–248.

- Koh, L.P.; Lee, T.M. Sensible consumerism for environmental sustainability. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 151, 3–6.

- Padfield, R.; Drew, S.; Syayuti, K.; Page, S.; Evers, S.; Campos-Arceiz, A.; Kangayatkarasu, N.; Sayok, A.; Hansen, S.; Schouten, G.; et al. Landscapes in transition: An analysis of sustainable policy initiatives and emerging corporate commitments in the palm oil industry. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 744–756.

- Vijay, V.; Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Smith, S.J. The Impacts of Oil Palm on Recent Deforestation and Biodiversity Loss. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159668.

- Li, T. After the land grab: Infrastructural violence and the “Mafia System” in Indonesia’s oil palm plantation zones. Geoforum 2018, 96, 328–337.

- McCarthy, J.F. Certifying in Contested Spaces: Private regulation in Indonesian forestry and palm oil. Third World Q. 2012, 33, 1871–1888.

- Brad, A.; Schaffartzik, A.; Pichler, M.; Plank, C. Contested territorialization and biophysical expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia. Geoforum 2015, 64, 100–111.

- Alonso-Fradejas, A.; Liu, J.; Salerno, T.; Xu, Y. Inquiring into the political economy of oil palm as a global flex crop. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 43, 141–165.

- Rulli, M.C.; Casirati, S.; Dell’Angelo, J.; Davis, K.F.; Passera, C.; D’Odorico, P. Interdependencies and telecoupling of oil palm expansion at the expense of Indonesian rainforest. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 499–512.

- Hospes, O. Marking the success or end of global multi-stakeholder governance? The rise of national sustainability standards in Indonesia and Brazil for palm oil and soy. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 425–437.

- Watts, J.D.; Pasaribu, K.; Irawan, S.; Tacconi, L.; Martanila, H.; Wiratama, C.G.W.; Musthofa, F.K.; Sugiarto, B.S.; Manvi, U.P. Challenges faced by smallholders in achieving sustainable palm oil certification in Indonesia. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105565.

- Schoneveld, G.C.; van der Haar, S.; Ekowati, D.; Andrianto, A.; Komarudin, H.; Okarda, B.; Jelsma, I.; Pacheco, P. Certification, good agricultural practice and smallholder heterogeneity: Differentiated pathways for resolving compliance gaps in the Indonesian oil palm sector. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101933.

- Dharmawan, A.H.; Mardiyaningsih, D.I.; Komarudin, H.; Ghazoul, J.; Pacheco, P.; Rahmadian, F. Dynamics of Rural Economy: A Socio-Economic Understanding of Oil Palm Expansion and Landscape Changes in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 213.

- Martens, K.; Kunz, Y.; Rosyani, I.; Faust, H. Environmental Governance Meets Reality: A Micro-Scale Perspective on Sustainability Certification Schemes for Oil Palm Smallholders in Jambi, Sumatra. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 33, 634–650.

- Brandi, C.; Cabani, T.; Hosang, C.; Schirmbeck, S.; Westermann, L.; Wiese, H. Sustainability Standards for Palm Oil: Challenges for smallholder certification under the RSPO. J. Environ. Dev. 2015, 24, 292–314.

- Jelsma, I.; Woittiez, L.S.; Ollivier, J.; Dharmawan, A.H. Do wealthy farmers implement better agricultural practices? An assessment of implementation of Good Agricultural Practices among different types of independent oil palm smallholders in Riau, Indonesia. Agric. Syst. 2019, 170, 63–76.

- Apriani, E.; Kim, Y.-S.; Fisher, L.A.; Baral, H. Non-state certification of smallholders for sustainable palm oil in Sumatra, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105112.

- Raharja, S.; Marimin; Machfud; Papilo, P.; Safriyana; Massijaya, M.Y.; Asrol, M.; Darmawan, M.A. Institutional strengthening model of oil palm independent smallholder in Riau and Jambi Provinces, Indonesia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03875.

- Glasbergen, P. Smallholders do not eat certificates. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 243–252.

- Naylor, R.L.; Higgins, M.M.; Edwards, R.B. Decentralization and the environment: Assessing smallholder oil palm development in Indonesia. Ambio 2019, 48, 1195–1208.

- Pacheco, P.; Levang, P.; Dermawan, A.; Schoneveld, G. The palm oil governance complex: Progress, problems and gaps. In Achieving Sustainable Cultivation of Oil Palm Volume 1: Introduction, Breeding and Cultivation Techniques; Rival, A., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1786761040.

- Faludi, A. Multi-level (territorial) governance: Three criticisms. Plan. Theory 2012, 13, 197–211.

- Antlöv, H.; Wetterberg, A.; Dharmawan, L. Village governance, community life, and the 2014 Village Law in Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2016, 52, 161–183.

- Cramb, R.; Curry, G.N. Oil palm and rural livelihoods in the Asia–Pacific region: An overview. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2012, 53, 223–239.

- Jessop, R. Hollowing out the ‘nation-state’ and multi-level governance. In A Handbook of Comparative Social Policy, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 11–26.

- Astari, A.J.; Lovett, J.C. Does the rise of transnational governance “hollow-out” the state? Discourse analysis of the mandatory Indonesian sustainable palm oil policy. World Dev. 2019, 117, 1–12.

- Wilson, C.; Morrison, T.; Everingham, J.-A. Linking the ‘meta-governance’ imperative to regional governance in resource communities. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 50, 188–197.

- Schouten, G.; Hospes, O. Public and Private Governance in Interaction: Changing Interpretations of Sovereignty in the Field of Sustainable Palm Oil. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4811.

- Peters, B.G. Governance is where you find it. Asian J. Political Sci. 2016, 24, 309–318.

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M. The two orders of governance failure: Design mismatches and policy capacity issues in modern governance. Policy Soc. 2014, 33, 317–327.

- Hudson, B.; Hunter, D.; Peckham, S. Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: Can policy support programs help? Policy Des. Pract. 2019, 2, 1–14.

- Hoornbeek, J.A.; Peters, B.G. Understanding policy problems: A refinement of past work. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 365–384.