Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Estrogens are among important contributing factors to many sex differences in neuroendocrine regulation of energy homeostasis induced by stress. Research in this field is warranted since chronic stress-related psychiatric and metabolic disturbances continue to be top health concerns, and sex differences are witnessed in these aspects.

- estrogen

- estrogen receptor

- hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

- energy-homeostasis

1. Introduction

Characteristic sex differences in energy metabolism and its dysregulation, induced by psychological stressors (e.g., restraint stress) and dietary stressors, such as under-feeding (e.g., dieting and fasting) and over-feeding (e.g., feeding a high-fat diet [HFD]), are witnessed in humans [1][2][3]. Besides regulating reproductive characteristics and functions, estrogens account for many sex differences in energy balance via regulating feeding behavior and energy metabolism [4]. Estrogens are heavily recognized for their protective effects on metabolism witnessed in both women and men [4]. Because one of the best ways to understand mechanisms of energy homeostasis in a laboratory setting is to perturb it, researchers discuss examples of stress-induced effects throughout. They generalize that stress-induced disturbance and threat to energy homeostasis, no matter the original stimulus, converge on activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Thus, researchers include specific examples from dietary stressors to psychological stressors. In order to comprehensively explain effects of estrogens on neuroendocrine regulation of energy homeostasis, researchers delve into fundamentals that refresh and expand readers’ understanding of the female reproductive cycles in humans and rodents, hormonal control of sexual differentiation of the brain, and the neurocircuitry underlying energy homeostasis.

1.1. Overview of Neuroendocrine Regulation of Energy Homeostasis

Homeostasis of energy metabolism is critical for survival. Accordingly, the neurobiology underlying these processes is constantly adapting to reflect the homeostatic needs of individual organisms, food availability and demands, and food wanting and value. The central nervous system (CNS) communicates with various peripheral organs and tissues via sympathetic efferents (i.e., the splanchnic nerves) and parasympathetic efferents (i.e., the vagus nerve) to control multiple aspects of energy expenditure, intake, and digestion and absorption [5]. Vagal afferents can either be stimulated directly by gastrointestinal tract tension changes from food or indirectly by chemical stimuli activating taste receptors, and subsequent release of gastrointestinal peptides [5]. The released peptides may induce appetite (e.g., ghrelin) or satiety (e.g., gastric leptin, cholecystokinin, glucagon-like peptide 1, and peptide YY) [5]. Circulating nutrients influence feeding through brainstem signaling to hypothalamic circuits [5]. Hypothalamic circuits are canonically known as the homeostatic circuits of energy metabolism [6]. Other notable peptides and their receptors involved in hypothalamic circuits of feeding and energy metabolism known to have anorexigenic or orexigenic functions are cannabinoid receptor type 1 [7] and cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript [8].

Feeding is not only guided by homeostatic energy needs which determine the number of calories ingested, but is also regulated by rewarding value of food comprising neuropeptide Y (NPY) [9] and dopamine [10] pathways in the hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic nuclei, which are associated with the sensory inputs of food such as smell and taste and modulated by physiological states such as hunger and satiety [11]. Control of energy homeostasis involves other aspects regulated by hypothalamic circuitry besides feeding, including regulation of lipid metabolism [12], distribution of adipose tissue [12], glucose metabolism [13], and insulin sensitivity [13]. Stress has been reported to alter feeding behavior, energy expenditure, and glucose and lipid metabolism [14].

1.2. Overview of Estrogen Regulation of Energy Homeostasis

Estrogens possess many different biological functions, and they are one of major factors underlying key metabolic and behavioral differences between men and women. One commonly cited indicator of how estrogen regulates metabolism is the prevalence of obesity and insulin resistance increasing among women after menopause when levels of endogenous estrogens decline [15]. For example, in an analysis of large-scale polling on a national level that included over 2500 American women, incidence of obesity increased from 37.0% in women 20–39 years of age to 44.6% in women 40–59 years of age [16]. Additionally, menopause is associated with increased central body fat accumulation in previously normal weight women, posited to be due to their declined estrogen levels [17]. Akin to postmenopausal compared with premenopausal women, ovariectomized rodents with depleted levels of circulating estrogen significantly increase their food intake and body weight gain [1][2][3]. Therefore, both human and animal studies support important roles of estrogen in metabolic regulation. Estrogens interact with estrogen receptors (ER) within brain regions underlying homeostatic regulation of energy metabolism have been studied to elucidate molecular mechanisms responsible for sex differences in energy homeostasis.

2. Energy Homeostasis across Reproductive Cycles Regulated by Estrogen

2.1. Reproductive Cycles in Humans and Rodents

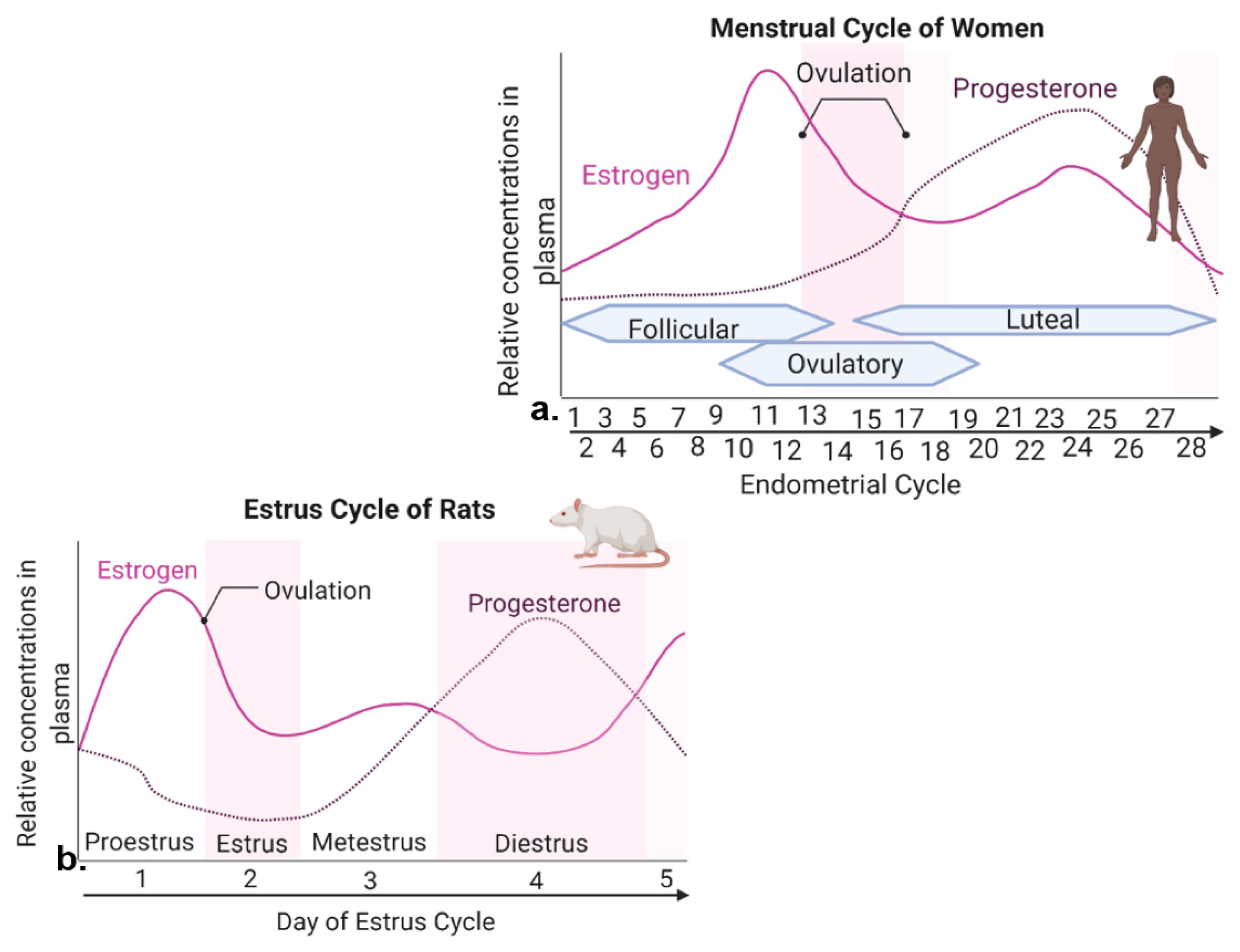

Rodent models are widely used in order to uncover molecular estrogen interactions in energy homeostasis. Therefore, it is worthwhile to briefly review woman and rodent reproductive cycles, noting their similarities and differences (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Levels of estrogen and progesterone during woman menstrual cycle and rodent estrous cycle. (a) The menstrual cycle of women takes place in ~28 days and consists of three prominent phases. The follicular phase is defined as the beginning of menstruation when shedding of the endometrium and bleeding occurs. During the beginning of this phase, estrogen and progesterone levels are low. Bleeding marks the start of a slight increase in follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. FSH levels decrease and one follicle proceeds to develop, producing estrogen. The ovulatory phase is marked by a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH, with ovulation occurring ~16–32 h post surge. Estrogen levels start to decrease, and progesterone increases. During the luteal phase, FSH and LH decrease, and the corpus luteum forms, which produces progesterone. Estrogen levels remain high, reaching its second largest peak. If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum degenerates, no longer producing progesterone, and estrogen levels decline, eventually causing the breakdown of uterus endometrium lining and the start of a new follicular phase. (b) The estrous cycle of rodents lasts ~4–5 days. Similar peaks of estrogen and progesterone are seen in menstrual cycle of women and estrous cycle of rats.

In women, the reproductive cycle is the menstrual cycle, also referred to as the endometrial cycle, which occurs ~28 days and consists of three prominent phases known as follicular, ovulatory, and luteal phases [18] (Figure 1a). The follicular phase distinguishes the beginning of menstruation, when shedding of the endometrium and bleeding occur [18]. During the beginning of this phase, the levels of estrogen and progesterone are low. Bleeding marks the start of a slight increase in follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, which causes the development of follicles in the ovaries [18]. FSH levels then decrease and only one follicle proceeds to develop, which produces estrogen [18]. The ovulatory phase is marked by a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH, causing ovulation (i.e., egg release) ~16–32 h post surge [18]. Estrogen levels start to decrease, and progesterone increases. During the luteal phase, levels of FSH and LH decrease, and the follicle forms into a corpus luteum, which produces progesterone and estrogen [18]. Estrogen levels are increased, reaching the second largest peak. High levels of estrogen and progesterone cause the uterus lining to thicken to prepare for possible implantation of a fertilized egg [18]. If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum degenerates, no longer producing progesterone, and as hormone levels decline, they eventually cause the breakdown of uterus endometrium lining and the start of a new follicular phase [18].

The rodent form of the reproductive cycle is called the estrous cycle [19], which occurs over a period of ~4–5 days. It consists of four main phases: proestrus, estrus, metestrus and diestrus [19] (Figure 1b), which correspond to three phases of the human menstrual cycle [19][20]. Notice that during both human and rodent cycles, as in many mammals, there are two large peaks in estrogen and one peak in progesterone levels (Figure 1) [18][19]. Specifically, in both rodents and women, the highest peak of estrogen proceeds ovulation [18][19]. The estrous cycle of rodents begins with proestrus, which is akin to the follicular phase in women that marks menstruation [19][20]. During proestrus, there is a rise in circulating estrogen and a small surge in prolactin, along with a rise in FSH and LH levels [19]. Proestrus is followed by a sharp decrease in estrogen levels and the start of ovulation, marking the estrous phase of rodents [19]. After estrus, metestrus and diestrus occur next, and are homologous to the early and late secretary phases of the human endometrial cycle, in which the progesterone peak takes place [19][20] (Figure 1). In summary, naturally cycling female rodents are avidly used laboratory models of women, with regular reproductive cycles across which similar feeding behavior and metabolic changes are witnessed in response to hormone fluctuation.

2.2. Energy Homeostasis across Female Reproductive Cycles

The reproductive cycles and related fluctuating levels of estrogens affect caloric intake and macronutrient selection differently. In many species including humans, caloric intake changes across reproductive cycles due to changes in meal size, with females eating the most calories when estrogen levels are low during metestrus, and eating the fewest calories when estrogen levels are high immediately prior to ovulation [17].

Interestingly, suppression of caloric intake by estrogen ceases when palatable food choices are offered alongside regular diet in female rhesus monkeys [21]. Food choice and macronutrient intake are also affected by the menstrual cycle in women. Self-assessed food craving and macro- and micro-nutrient intake in 259 healthy women was analyzed for a period of two complete menstrual cycles [22]. During the late luteal phase when estrogen levels are at their lowest level prior to menstruation, appetite and food craving for chocolate and sweet and salty flavors were higher, comparing with follicular and ovulatory phases when estrogen levels increase and peak during late follicular phase and beginning of ovulation [22]. Interestingly, total protein intake and percentage of caloric intake from protein were greater during the mid-luteal phase with the second peak of estrogen levels, comparing with the ovulatory phase following the first and higher peak of estrogen (Figure 1a) [22].

In summary, the relationship between circulating hormone levels, feeding behavior, and energy metabolism is complex, and estrogen effects are dynamic across the female cycles in women and experimental animals.

2.3. Female Cycles Regulated by Estrogen

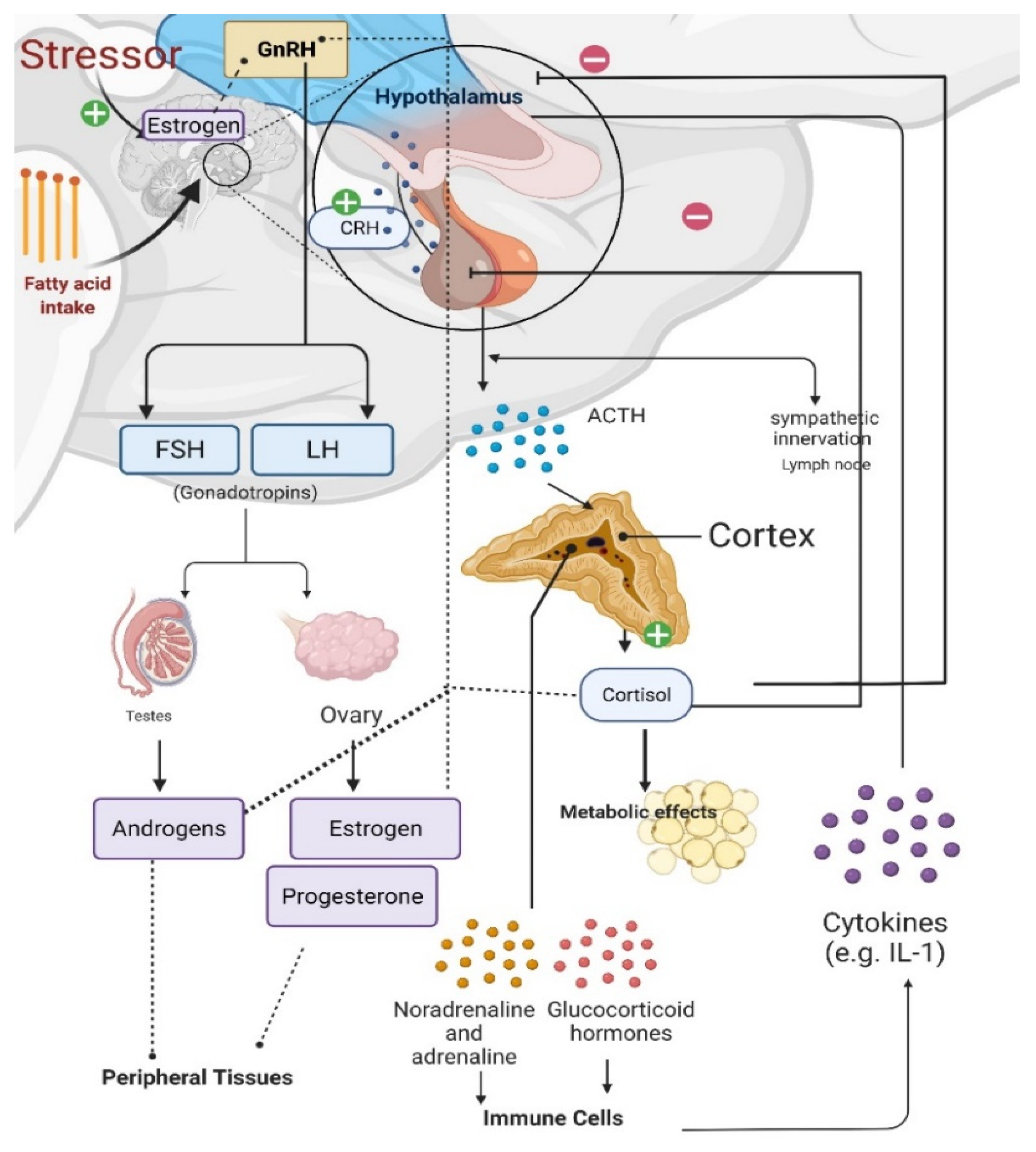

Estrogens plays critical roles in regulating great variety of physiological and behavioral functions. In females, the majority of estrogens, predominantly of the type 17β-estradiol (17β-E2) are synthesized in the periphery (i.e., ovaries) from cholesterol via the steroidogenic pathway involving a series of biochemical reactions [23]. Estrogen steroidogenesis also occurs in Leydig and germ cells of the testis in males, although levels of produced estrogen are relatively low [24]. In both males and females, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus triggers the anterior pituitary to secrete gonadotropins LH and FSH, which act on the gonads to stimulate steroidogenesis and gametogenesis [25] (Figure 2). In females, ovarian 17β-E2 synthesis and release from the ovaries negatively and positively regulates GnRH release in a pulsatile manner, although many effects of CNS-derived neuroestradiol on GnRH have been found to be more responsible for regulating GnRH (Figure 2) [25][26][27][28].

Figure 2. Effects of stress on the gonadal axis, immune cells, and metabolism. Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) release from the hypothalamus causes the anterior pituitary to secrete gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH]), which stimulate gonadal steroidogenesis. Estradiol synthesis and release from the ovaries regulates GnRH release. Estrogens can also be synthesized in the brain of males and females from androgens via aromatase in neurons; and estrogens can be synthesized in and have various effects at peripheral tissues. When the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is stimulated, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus triggers adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release from the anterior pituitary and increased cortisol production in the adrenal glands. Cortisol provides negative feedback to both the hypothalamus and pituitary; however, prolonged stress impairs this negative feedback regulation, causing long-lasting psychological and metabolic maladies. Prolonged fatty acid intake causes proliferative cytokines in the hypothalamus of males, which is protected in females.

Prolonged stress and increased glucocorticoid levels induce immune responses, elevate circulating cytokine levels, and dysregulate GnRH expression [25]. Therefore, the HPA axis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, and immune cells all interact with each other (Figure 2) [29][30]. During the HPA axis response to stress, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) is released from the hypothalamus, causing the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary and subsequent production of cortisol (in rodents)/corticosterone (in humans) from the adrenal cortex [29][31]. Sympathetic activation during stress also regulates energy metabolism along with cardiovascular and pulmonary responses via sympathoneural (i.e., sympathetic innervation) and sympathoadrenomedullary (i.e., noradrenaline and adrenaline) systems (Figure 2) [32].

Major sex differences exist in stress-induced and stress-related metabolic disorders or disease states, pointing to differential interactions between the HPG axis, HPA axis, and immune cells [29][33][34]. For example, prolonged HFD feeding causes inflammation with elevated proinflammatory cytokines in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and cortex of males but not females [35]. A recent experiment underlying female metabolic protection against HFD feeding has demonstrated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) as a regulator of ERα transcription [35]. Specifically, chronic HFD exposure for 16 weeks causes increased proinflammatory cytokines, but reduced PGC-1α and ERα transcription, in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) of male mice, causing a metabolic dysfunction phenotype of myocardial complications. Conversely, both PGC-1α knockout (KO) and ERα overexpression resulted in protection from these metabolic complications [35]. PGC-1α effects are likely to be upstream of ERα. Even in male mice, ERα can be protective against HFD feeding-related metabolic disorders. Novel regulators of ERα are still being discovered. Future studies that delve into the molecular details and underlying mechanisms of such sex differences await discovery.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11050879

References

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Sex differences in metabolic homeostasis, diabetes, and obesity. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2015, 6, 14.

- Chella Krishnan, K.; Mehrabian, M.; Lusis, A.J. Sex differences in metabolism and cardiometabolic disorders. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2018, 29, 404–410.

- Shi, H.; Seeley, R.J.; Clegg, D.J. Sexual differences in the control of energy homeostasis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 396–404.

- Xu, Y.; López, M. Central regulation of energy metabolism by estrogens. Mol. Metab. 2018, 15, 104–115.

- Camilleri, M. Peripheral mechanisms in appetite regulation. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 1219–1233.

- Yeo, G.S.H.; Heisler, L.K. Unraveling the brain regulation of appetite: Lessons from genetics. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1343–1349.

- Koch, M. Cannabinoid receptor signaling in central regulation of feeding behavior: A mini-review. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 293.

- Lau, J.; Herzog, H. CART in the regulation of appetite and energy homeostasis. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 313.

- Pelletier, G.; Simard, J. Dopaminergic regulation of pre-proNPY mRNA levels in the rat arcuate nucleus. Neurosci. Lett. 1991, 127, 96–98.

- Huang, X.F.; Yu, Y.; Zavitsanou, K.; Han, M.; Storlien, L. Differential expression of dopamine D2 and D4 receptor and tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in mice prone, or resistant, to chronic high-fat diet-induced obesity. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 135, 150–161.

- Rolls, E.T. Taste, olfactory and food texture reward processing in the brain and the control of appetite. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 488–501.

- Pa, B. The regulation of adipose tissue regulation in humans. Int. J. Obes. Relat Metab. Disord 1996, 20, 291–302.

- Ono, H. Molecular mechanisms of hypothalamic insulin resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1317.

- Rabasa, C.; Dickson, S.L. Impact of stress on metabolism and energy balance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 71–77.

- De Paoli, M.; Zakharia, A.; Werstuck, G.H. The role of estrogen in insulin resistance: A review of clinical and preclinical data. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1490–1498.

- Flegal, K.M.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Trends in obesity among adults in the united states, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016, 315, 2284–2291.

- Asarian, L.; Geary, N. Sex differences in the physiology of eating. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 305, R1215–R1267.

- Mihm, M.; Gangooly, S.; Muttukrishna, S. The normal menstrual cycle in women. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 124, 229–236.

- Ajayi, A.F.; Akhigbe, R.E. Staging of the estrous cycle and induction of estrus in experimental rodents: An update. Fertil. Res. Pract. 2020, 6, 5.

- Heape, W. Memoirs: The “sexual season” of mammals and the relation of the “pro-oestrum” to menstruation. J. Cell Sci. 1900, s2-44, 1–70.

- Johnson, Z.P.; Lowe, J.; Michopoulos, V.; Moore, C.J.; Wilson, M.E.; Toufexis, D. Oestradiol differentially influences feeding behaviour depending on diet composition in female rhesus monkeys. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 25, 729–741.

- Gorczyca, A.M.; Sjaarda, L.A.; Mitchell, E.M.; Perkins, N.J.; Schliep, K.C.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Mumford, S.L. Changes in macronutrient, micronutrient, and food group intakes throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy, premenopausal women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1181–1188.

- Cui, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, R. Estrogen synthesis and signaling pathways during aging: From periphery to brain. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 197–209.

- Hess, R. Estrogen in the adult male reproductive tract: A review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1, 52.

- Tzoupis, H.; Nteli, A.; Androutsou, M.E.; Tselios, T. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and GnRH receptor: Structure, function and drug development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 6136–6158.

- Ramirez, V.D.; Abrams, R.M.; McCann, S.M. Effect of estradiol implants in the hypothalamophypophysial region of the rat on the secretion of luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology 1964, 75, 243–248.

- Mizuno, M.; Terasawa, E. Search for neural substrates mediating inhibitory effects of oestrogen on pulsatile luteinising hormone-releasing hormone release in vivo in ovariectomized female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J. Neuroendocrinol. 2005, 17, 238–245.

- Levine, J.E.; Norman, R.L.; Gliessman, P.M.; Oyama, T.T.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Spies, H.G. In vivo gonadotropin-releasing hormone release and serum luteinizing hormone measurements in ovariectomized, estrogen-treated rhesus macaques. Endocrinology 1985, 117, 711–721.

- Handa, R.J.; Weiser, M.J. Gonadal steroid hormones and the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 197–220.

- Toufexis, D.; Rivarola, M.A.; Lara, H.; Viau, V. Stress and the reproductive axis. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 26, 573–586.

- Sheng, J.A.; Bales, N.J.; Myers, S.A.; Bautista, A.I.; Roueinfar, M.; Hale, T.M.; Handa, R.J. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: Development, programming actions of hormones, and maternal-fetal interactions. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 601939.

- Kvetnansky, R.; Lu, X.; Ziegler, M.G. Stress-triggered changes in peripheral catecholaminergic systems. Adv. Pharmacol. 2013, 68, 359–397.

- Fernández-Guasti, A.; Fiedler, J.L.; Herrera, L.; Handa, R.J. Sex, stress, and mood disorders: At the intersection of adrenal and gonadal hormones. Horm. Metab. Res. 2012, 44, 607–618.

- Pasquali, R.; Vicennati, V.; Gambineri, A.; Pagotto, U. Sex-dependent role of glucocorticoids and androgens in the pathophysiology of human obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1764–1779.

- Morselli, E.; Fuente-Martin, E.; Finan, B.; Kim, M.; Frank, A.; Garcia-Caceres, C.; Navas, C.R.; Gordillo, R.; Neinast, M.; Kalainayakan, S.P.; et al. Hypothalamic PGC-1α protects against high-fat diet exposure by regulating ERα. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 633–645.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!