Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Anthropology

Tourist activity is the main cause of seasonal activation of rural areas. The largest seasonal fluctuations were registered in mountain areas and spa resorts. For mountain areas, the highest seasonality is in the winter months (peak—January/February), and lowest is in the summer season. The seasonal character of spa centers indicates the similar trend, generally less pronounced (peak—January), however, with higher seasonality during the summer.

- rural areas

- seasonality coefficient

- nighttime lights (NTL)

- tourism

- Serbia

1. Detailed Analysis

1.1. Seasonality Coefficient Based on Nighttime Lights (Scos)

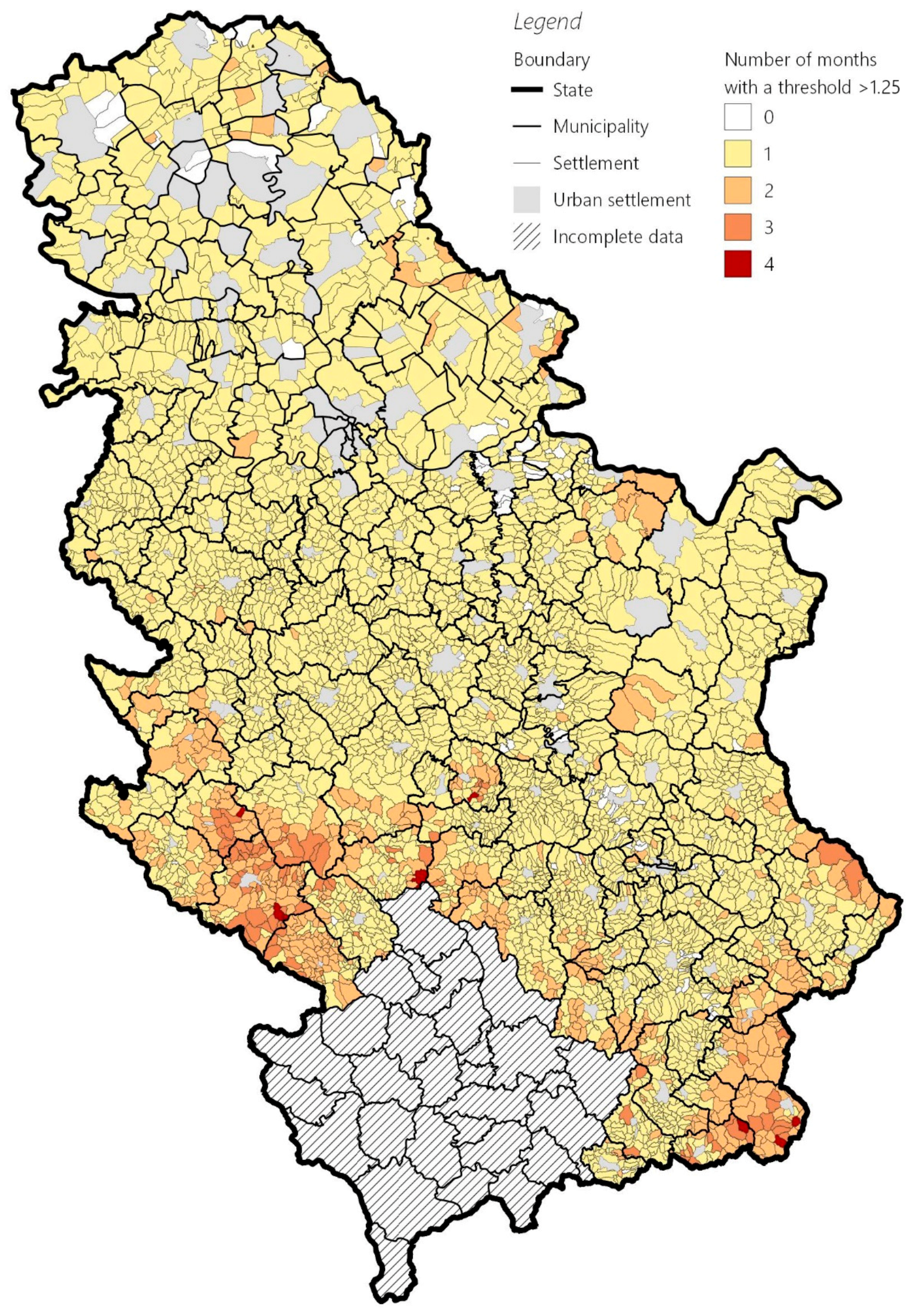

The first step in detecting seasonality was performed by calculating the seasonality coefficient based on the monthly values of NTL data. Based on this parameter, 687 settlements (15.1% of total settlements in Serbia) were selected, which show a certain degree of seasonality, i.e., in which the obtained Scos value is higher than the established threshold—1.25 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Seasonally activated settlements in Serbia, 2015–2019.

In this group, 587 settlements recorded a low seasonality distributed in two months during one year, which represents 85.4% within seasonally active settlements. This group of settlements is highly heterogeneous, in which it is impossible to identify certain spatial patterns of seasonality as well as the causes of their occurrence. As such, this group does not indicate representative seasonality of the rural areas, which led to their exclusion from deeper analysis; however, this group indicates the spatial spreading of the phenomenon seasonality on particular areas in Serbia (e.g., Zlatibor Mt., Stara planina Mt., Kopaonik Mt., Zlatar Mt., etc.) (Figure 1).

Significant variations in brightness during the year were recorded in 92 settlements (13.4%) within three months of seasonal activation, and eight settlements (1.2%) with four months of seasonal fluctuation. Considering that this is a more significant period of the pronounced seasonality, this group of 100 settlements in rural Serbia is segregated for further analysis.

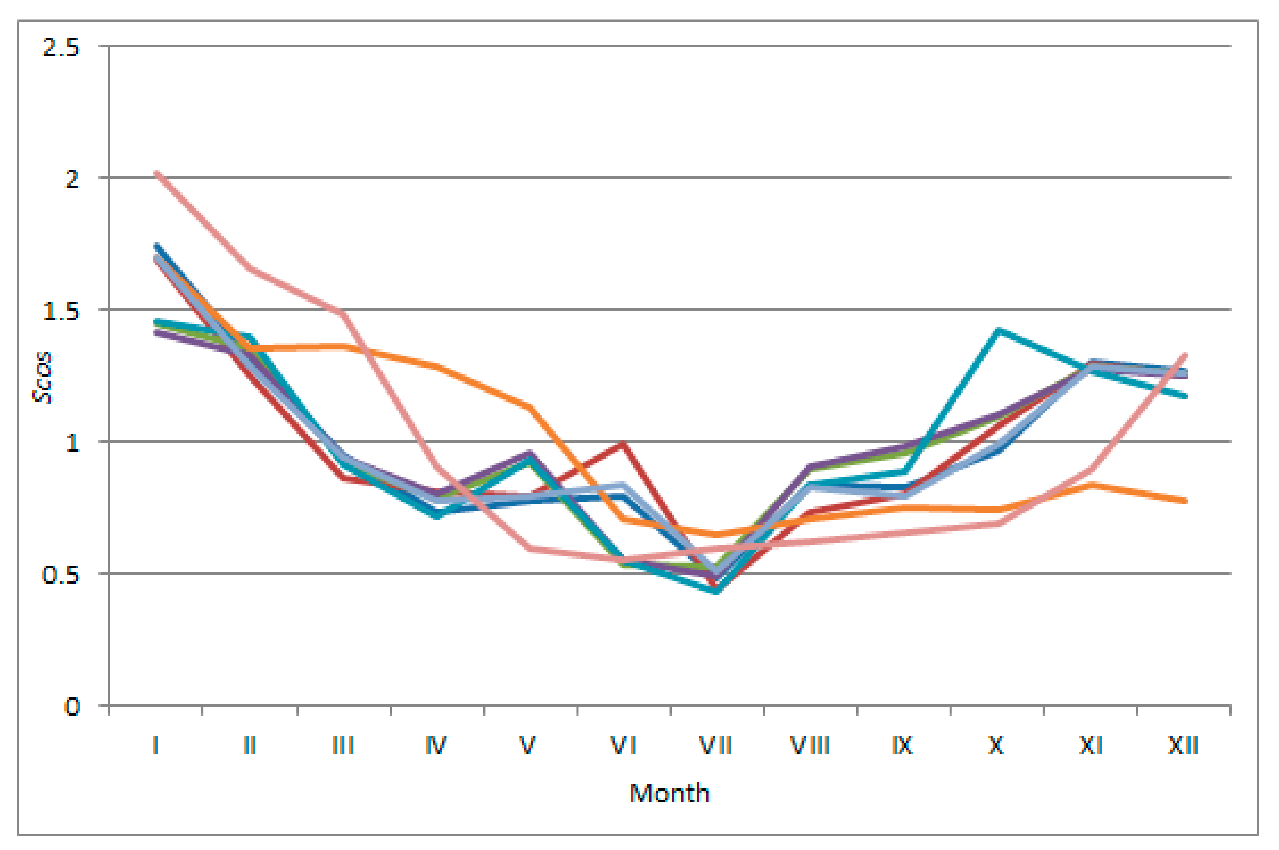

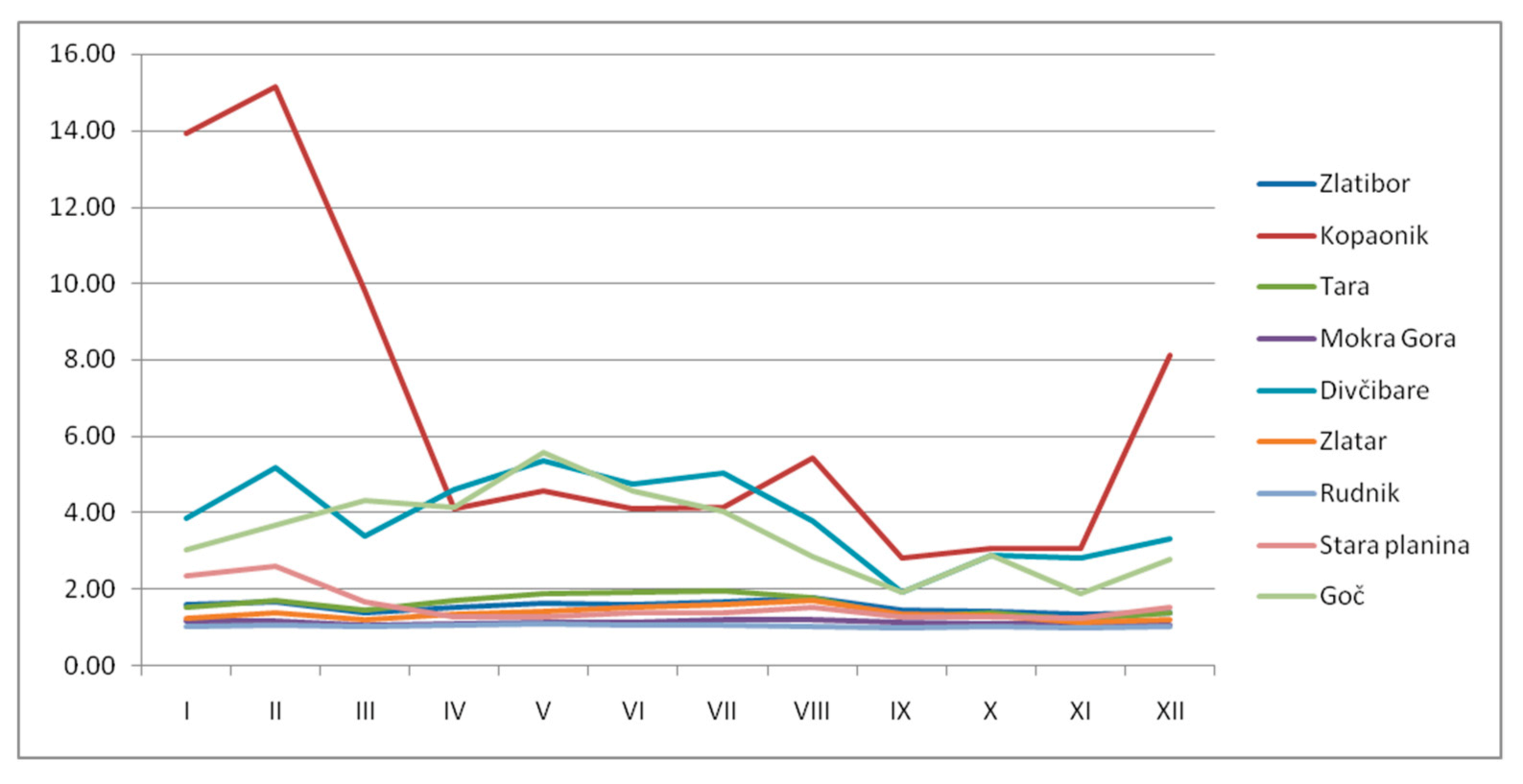

The most intensive seasonality character was registered in the eight settlements located in the southern mountainous part of the country (Figure 1). Highest values of the coefficient are in the winter months (peak is in January and February), while the lowest values are related to the summer season (Figure 2). The largest seasonal fluctuations were registered in mountain tourist areas—Kopaonik Mt., Zlatar Mt., Goč Mt., Dukat Mt., then in nature reserves and transit border areas, as well, presented on the Figure 2 with orange, purple, red and blue line.

Figure 2. Seasonality coefficient for settlements activated for 4 months per year.

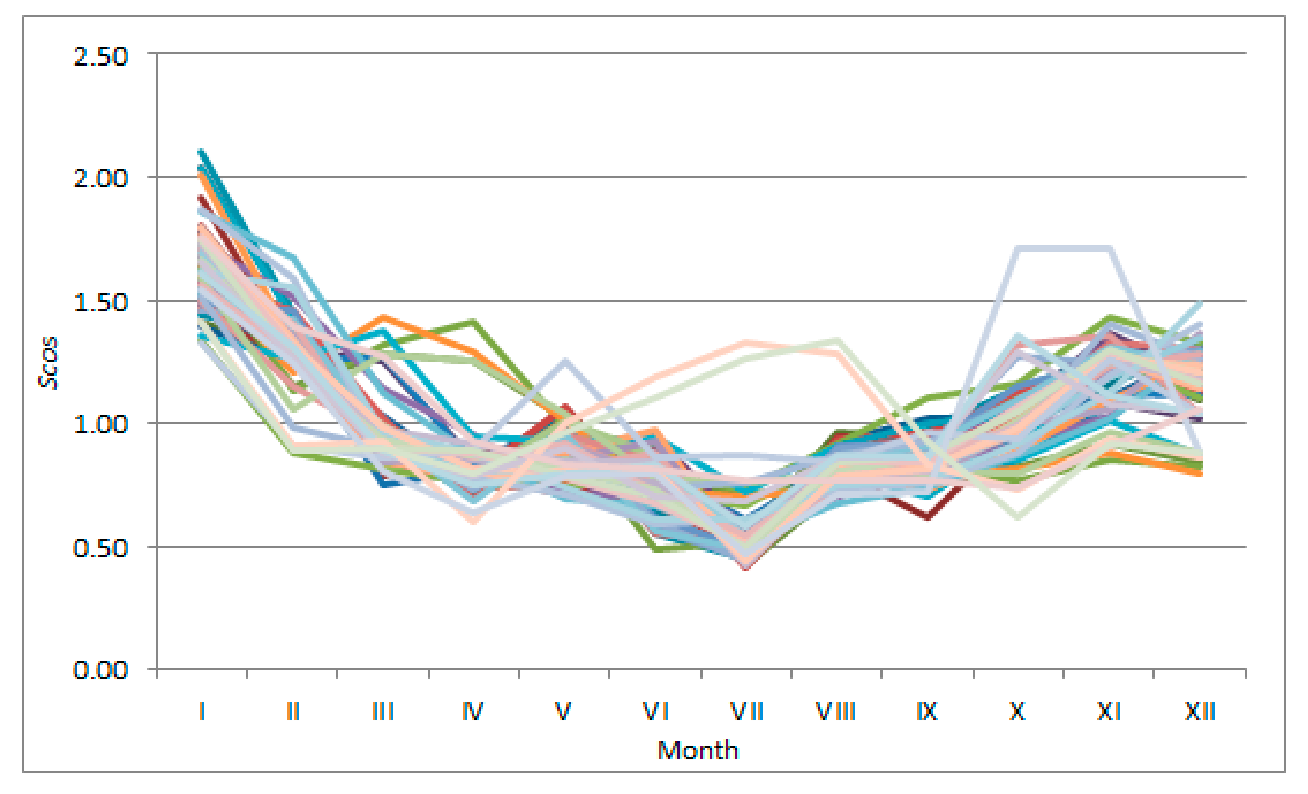

Significant seasonality in the use of rural areas is observed in settlements where higher values of the coefficient are registered for three months during the year, as well. This group of settlements is numerous and has a heterogeneous structure compared to the previous one, however, showing a certain rule of seasonal activation. The Figure 3 shows the trend of seasonality in this group of settlements (93), presented with different line colors. The seasonality peak is characteristic for winter months (January, February, December), while the decrease of seasonality is related to the summer season (Figure 3). The identified spatial patterns of seasonality that the previous group has shown fully correspond to this group as well, however, with wider territory coverage. So, the seasonality was influenced by tourist activity in the mountainous area—Kopaonik Mt., Zlatar Mt., Zlatibor Mt., Stara planina Mt., Goč Mt., Golija Mt., Vršačke planine Mt. and Dukat Mt., seasonal agricultural activities (Pešter Plateau), transit areas, nature reserves—Uvac, Pčinja, Jerma, etc., lakes—Zlatarsko jezero Lake, Vlasinsko jezero Lake, etc., and spa centers, as well (Figure 1). Some locations recorded the peaks during the spring months, which are related to excursion tourism in the lower mountain and accessible areas (Goč Mt., Vršačke planine Mt.), while the summer peak is noticed in places located near frequent infrastructure corridors, which is associated with transit tourism.

Figure 3. Seasonality coefficient for settlements activated for 3 months per year.

1.2. Seasonality Coefficient Based on Official Statistics (Scot)

The official statistical data recording the seasonal trends on the territory of Serbia are limited, since they relate to the most attractive and valorised tourist places. This refers to monthly fluctuations in the number of tourists within the mountain tourist areas and spa resorts. Based on that, the derived seasonality coefficient indicates deviations from the average monthly values, and highlights a problem which should be further studied.

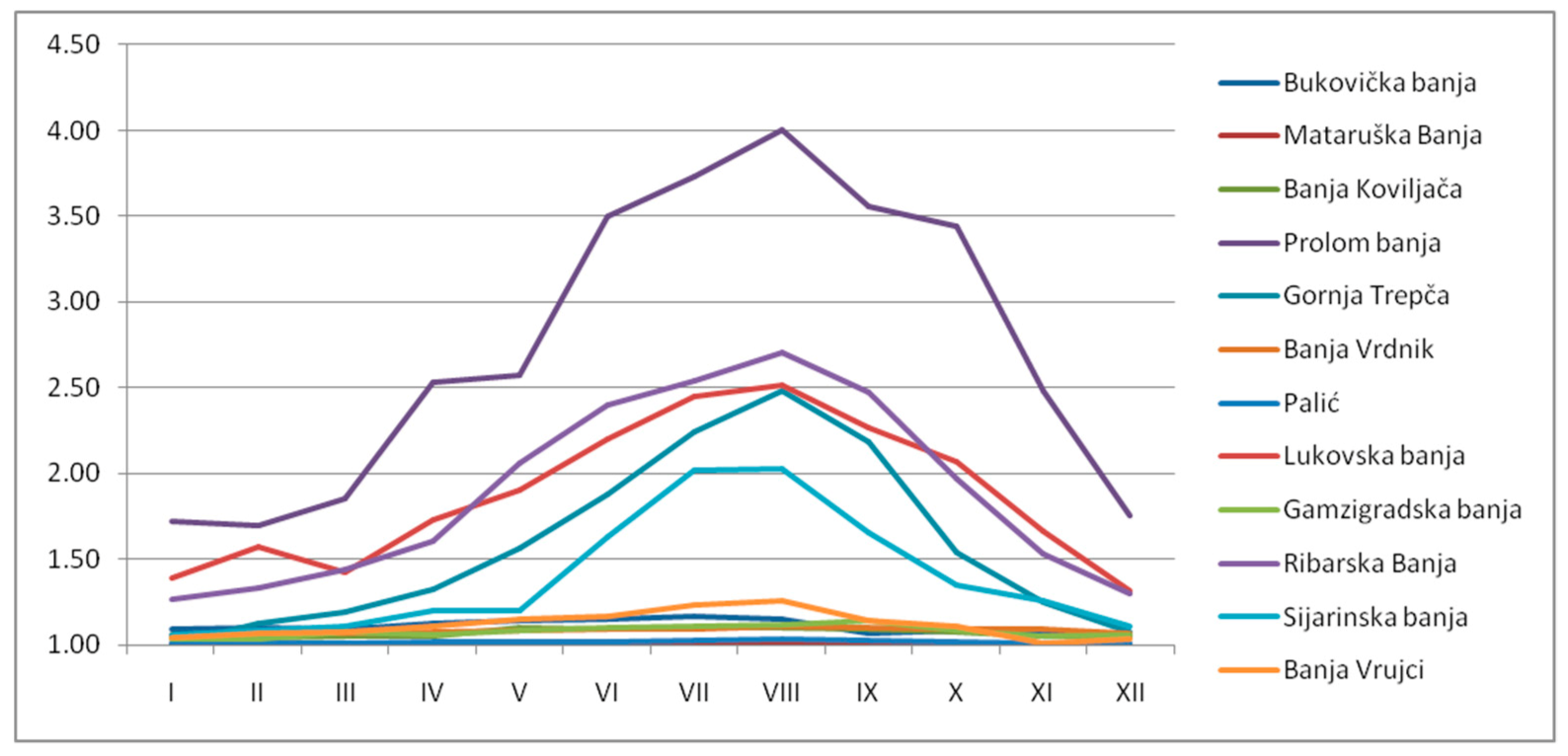

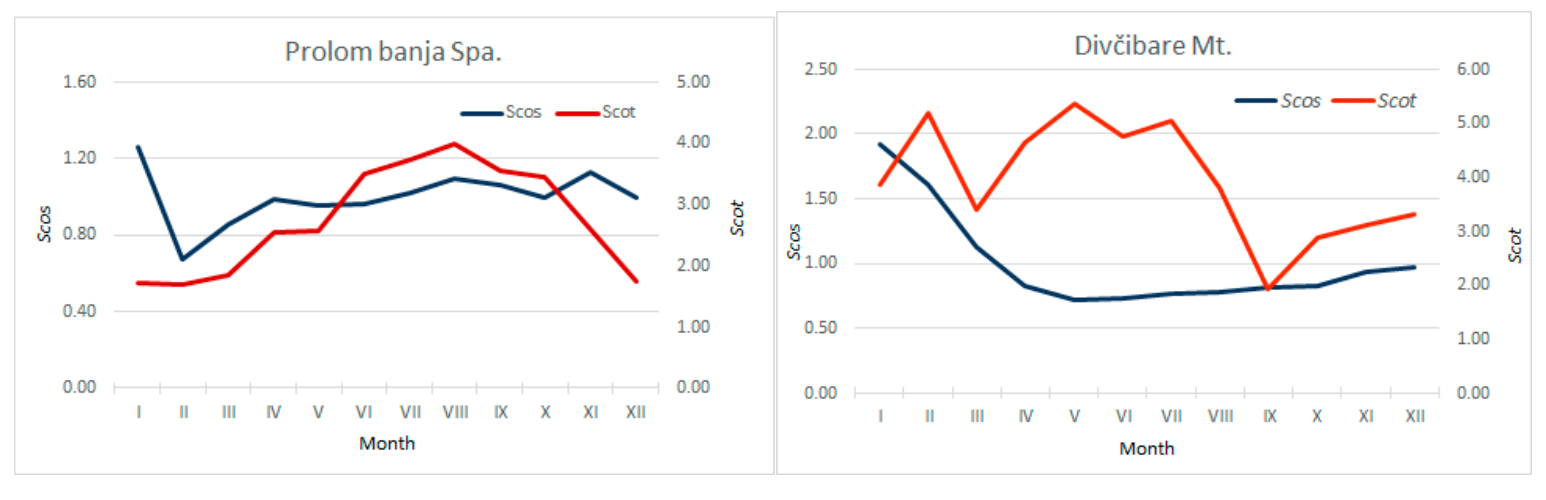

Generally speaking, the seasonal coefficient values, related to a narrow data set on tourist trends, showed minor oscillations. However, they can be observed for certain limited areas. The seasonality coefficient values vary as a direct result of the number of tourist arrivals’ oscillations. Observing the spa tourist places in the rural area of Serbia, it can be noticed that the seasonal character is related to the summer season, when the highest coefficient values are recorded (Figure 4). For some spa centers, there are very high seasonality coefficients (Prolom Spa, Lukovska Spa, Ribarska Banja Spa, Gornja Trepča Spa) (Figure 4), while in others, the seasonality is fairly equal. Some of the spa centers have a weak tourist offer and a small number of visitors (Gamzigrad Spa, Rusanda Spa, Mataruška banja Spa), so no oscillations are detected. On the other hand, others, some spa centers have continuity in the number of visitors during the year (Palić Spa, Bukovička Banja Spa, Banja Koviljača Spa, Vrdnik Spa and Kanjiža Spa), where seasonal oscillations are negligible.

Figure 4. Seasonality of the spa touristic centers, 2015–2019.

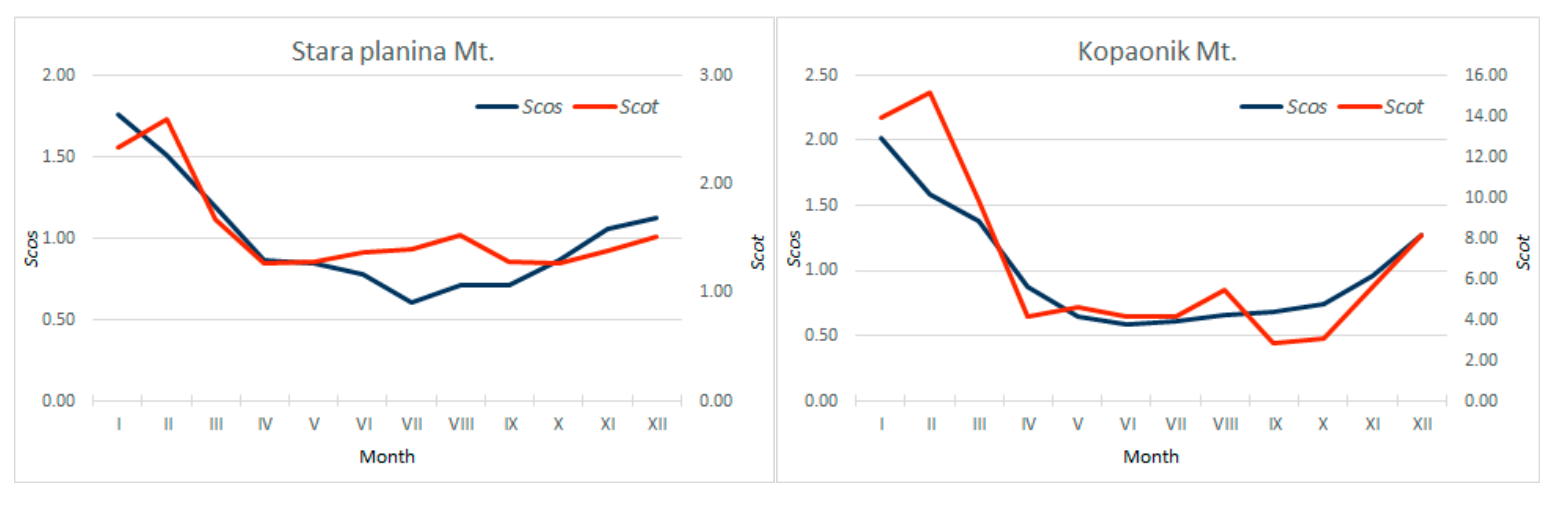

Tourist mountain areas have a more pronounced seasonality, which is especially emphasized for Kopaonik Mt., as the most important winter tourist center in Serbia. The seasonal peak is related to the winter months. Goč Mt., Stara planina Mt., and Divčibare Mt., which are smaller and less developed and equipped tourist centers, also showed significant seasonality. Some of them, like Goč Mt., Divčibare Mt., and Tara Mt., express continual higher values of the seasonal coefficient during the spring and summer months, as well, which indicates various visitors’ preferences and diversified tourist activities. The second peak has been clearly noticed for Kopaonik Mt. but is more pronounced compared to the other mountainous areas (Figure 5). Other mountain places record seasonality, as well, predominantly during the winter season, but with lower coefficient values (Figure 5). Likewise, some mountain places recorded uniform coefficients during the whole year due to the fact that they have continuity in tourist traffic, such as Zlatibor Mt., which is conditioned with a reputation as a mountainous summer–winter resort and is one of the most developed tourist areas [1], and tourist turnover has become more massive during the time.

Figure 5. Seasonality of the mountain touristic centers, 2015–2019.

1.3. Intertwining of the Seasonality Coefficients

In order to determine the degree of correlation between the calculated seasonality coefficients—Scos and Scot—the seasonality coefficients for selected rural areas are intertwined (Figure 6). After performing the Pearson correlation, it was found that there is a statistically significant relation in places with more massive and specialized tourism and spatially limited occurrence of seasonality (R2 has values of 0.93, 0.86, and 0.26 for Kopaonik Mt., Stara planina Mt, and Prolom banja Spa, respectively), while in other places, the statistical significance decreases. The positive and significant correlation between two applied methods justified the use of NTL as a proxy for investigation of the seasonality phenomenon.

Figure 6. Intertwined seasonality coefficients for selected case studies.

Figure 6. Intertwined seasonality coefficients for selected case studies.1.4. Case Study of the Rural Areas Seasonal Activation Based on the Tourist Activity

Six representative mountain areas and three spa centers are singled out, in order to better understand annual seasonality distribution on a monthly basis (Table 1). The observed mountain places are the most visited destinations. However, based on the Scos seasonality coefficient, it can be noticed that the increased activation in these places varies during the year. The winter season is the most intense in both types of observed places, especially the month of January. On the contrary, for observed mountain places, during the summer period, a decrease of values is detected. However, in mountain areas with less developed and narrowed tourist offers, a slightly higher intensity of NTL is registered (e.g., Divčibare Mt., Zlatar Mt., Tara Mt.), which indicates the possibility of activation in those months, as well (Table 1).

Table 1. The monthly Scos values for the selected tourist areas (the months with the highest and lowest SOL are bolded).

| Touristic Areas (Destination) | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divčibare Mt. | 1.92 | 1.60 | 1.12 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.97 |

| Stara planina Mt. | 1.76 | 1.51 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 1.05 | 1.12 |

| Kopaoonik Mt. | 2.01 | 1.58 | 1.38 | 0.87 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 1.28 |

| Zlatar Mt. | 1.66 | 1.34 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.18 |

| Zlatibor Mt. | 1.80 | 1.34 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 1.14 |

| Tara Mt. | 1.88 | 1.32 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 1.05 | 1.06 |

| Ribarska banja Spa | 2.00 | 1.07 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 1.15 | 1.17 |

| Prolom banja Spa | 1.26 | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.0 | 1.13 | 1.0 |

| Lukovska banja Spa | 1.42 | 1.03 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 1.09 | 1.13 |

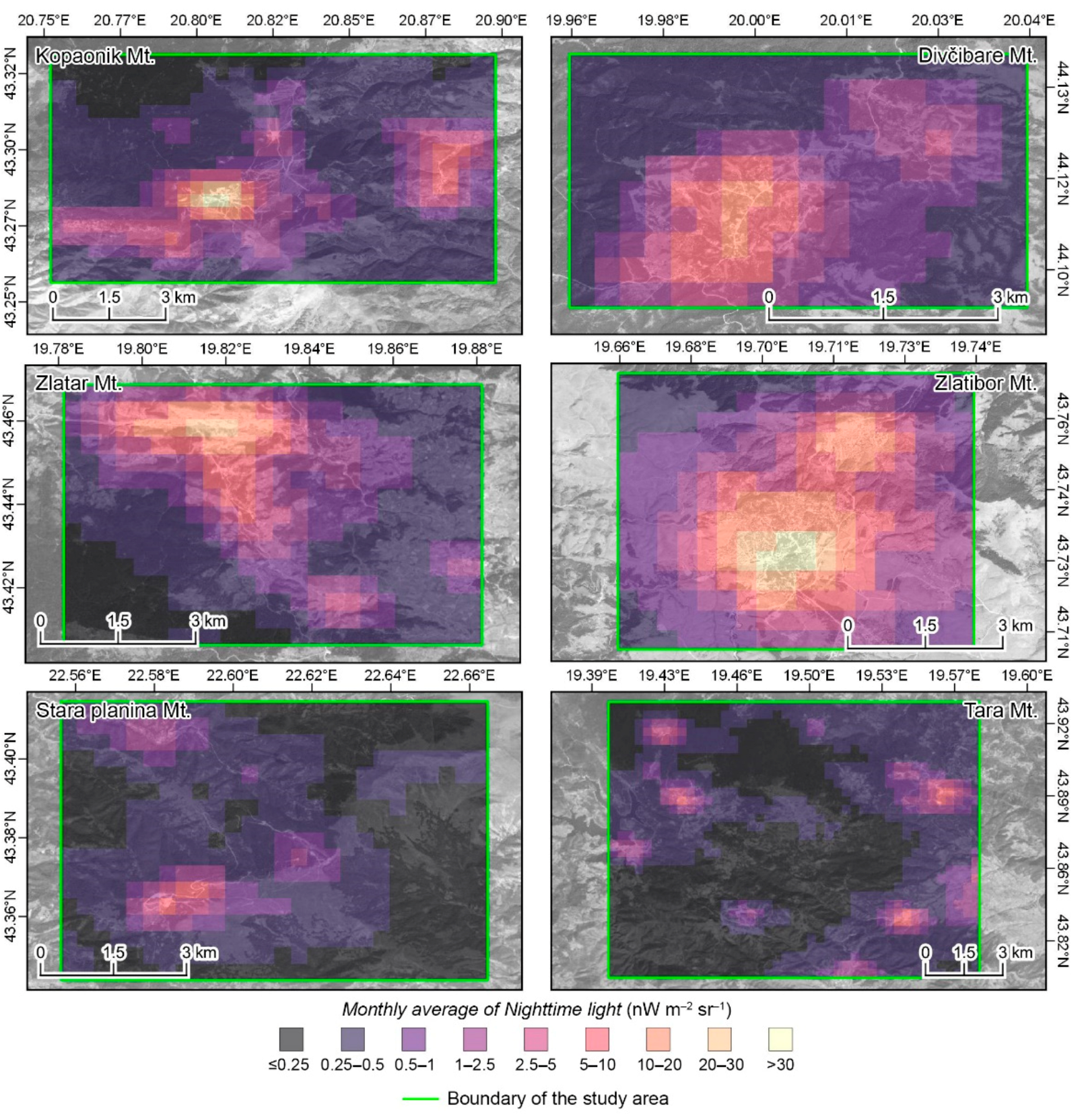

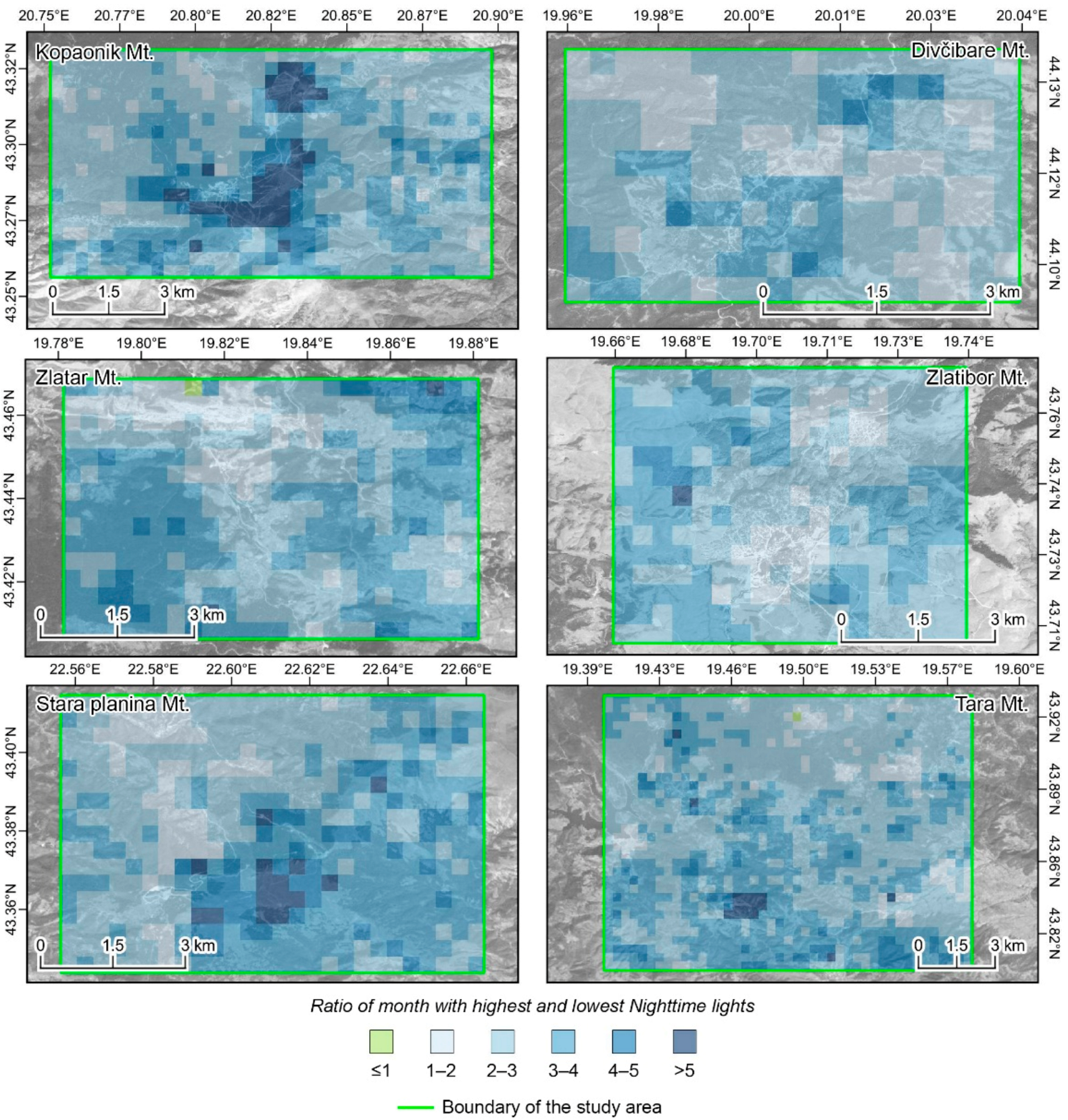

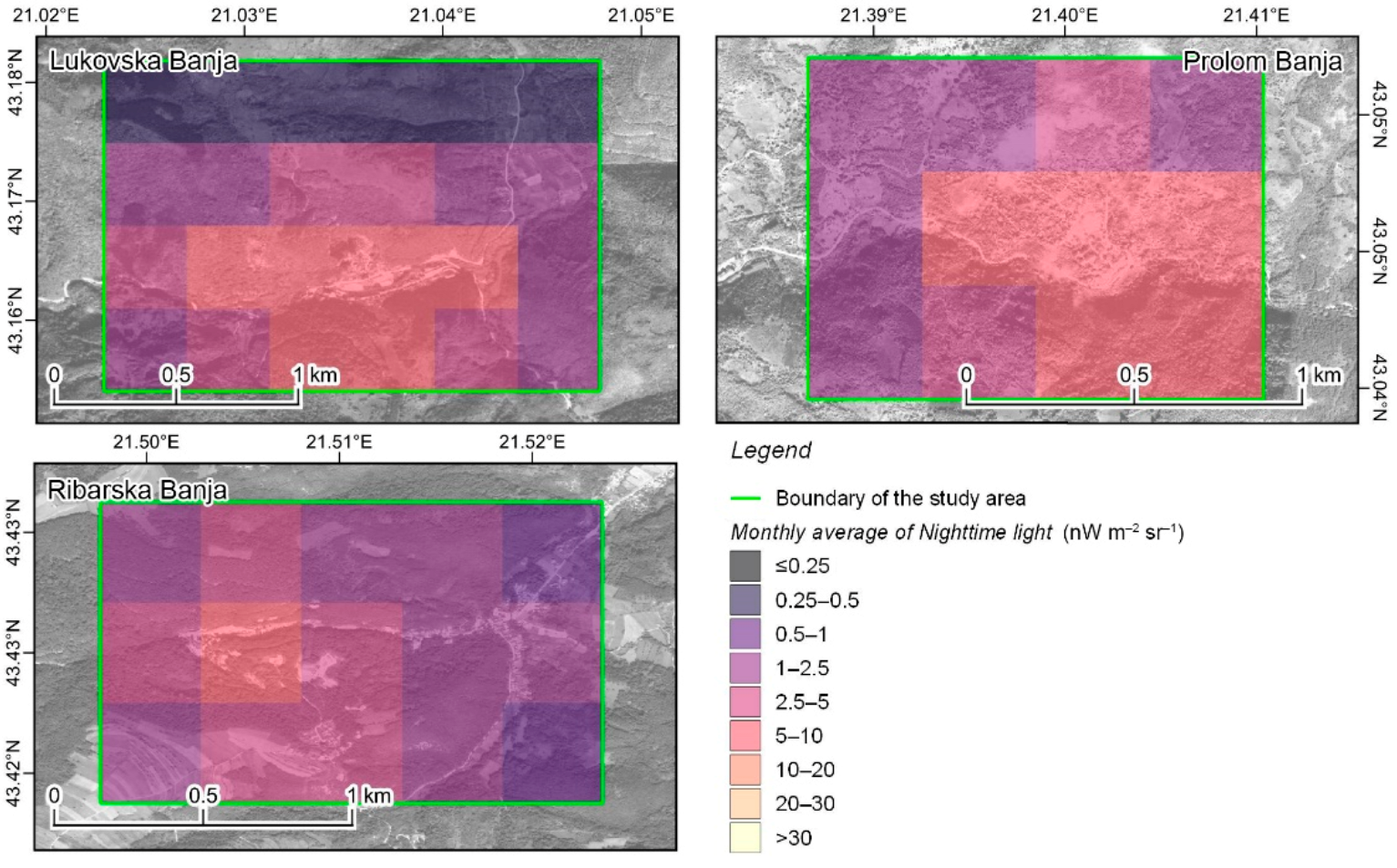

Seasonality expressed by the variation of NTL is especially pronounced in the area of Kopaonik Mt., where the highest values of the coefficient are recorded. Likewise, pronounced seasonality is present in the central part of the Kopaonik Mt. where the activity is highest and which influenced the development of secondary tourist sites (Figure 6). The NTL’s intensity gradually decreases, distancing from the central part. On the other hand, Zlatibor Mt. has developed a wider mountain area with high-intensity activity, as a result of the strong and diverse tourist offerings which led to the expansion of the tourist season, or vice versa. It is noticed that enhanced activity is provided along the access roads and in the area of weekend settlements, which indicates the influx of population in the observed period. A similar phenomenon is observed in Stara planina Mt., Zlatar Mt., and Divčibare Mt., where the spread of the phenomenon is registered, but with lower intensity of NTL. The weakest seasonality and activation of rural areas is recorded in Tara Mt., where there is a polycentric and dispersed spatial pattern of rural settlements identified, but insufficient for the integration of the surrounding area (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Average monthly nighttime lights (NTL) (2015–2019) for the selected mountain tourist areas.

However, the findings that illustrate the part of the rural area that is actually most activated during the five-year period are interesting. These results were obtained based on the ratio of the month in which the highest value of NTL intensity was recorded (January) and the month with the weakest radiance for selected cases. When it comes to mountain tourist areas, the same pattern of spatial changes has been identified. The central part of the mountain areas is exposed to the weakest changes in intensity in all cases. This is especially noticeable in Kopaonik Mt., Zlatibor Mt., Zlatar Mt., and Divčibare Mt. (Figure 8). This could be explained with the fact that the central parts of the observed areas are most densely built and with a highest concentration of tourist facilities, population, activities, and complementary functions, which have a constant radiance throughout the year. The high correlation between the intensity of NTL and infrastructure and urban fabric has been indicated by previous research [2][3][1][4][5]. On the other hand, the area outside the central core is exposed during the year to the largest seasonal fluctuations in terms of radiance intensity, which is related to the presence of the seasonal population in that area. Activation of these areas indicates the spread of primary tourist activity that has a seasonal character [1].

Figure 8. Ratio of the months with highest and lowest NTL for selected mountain areas.

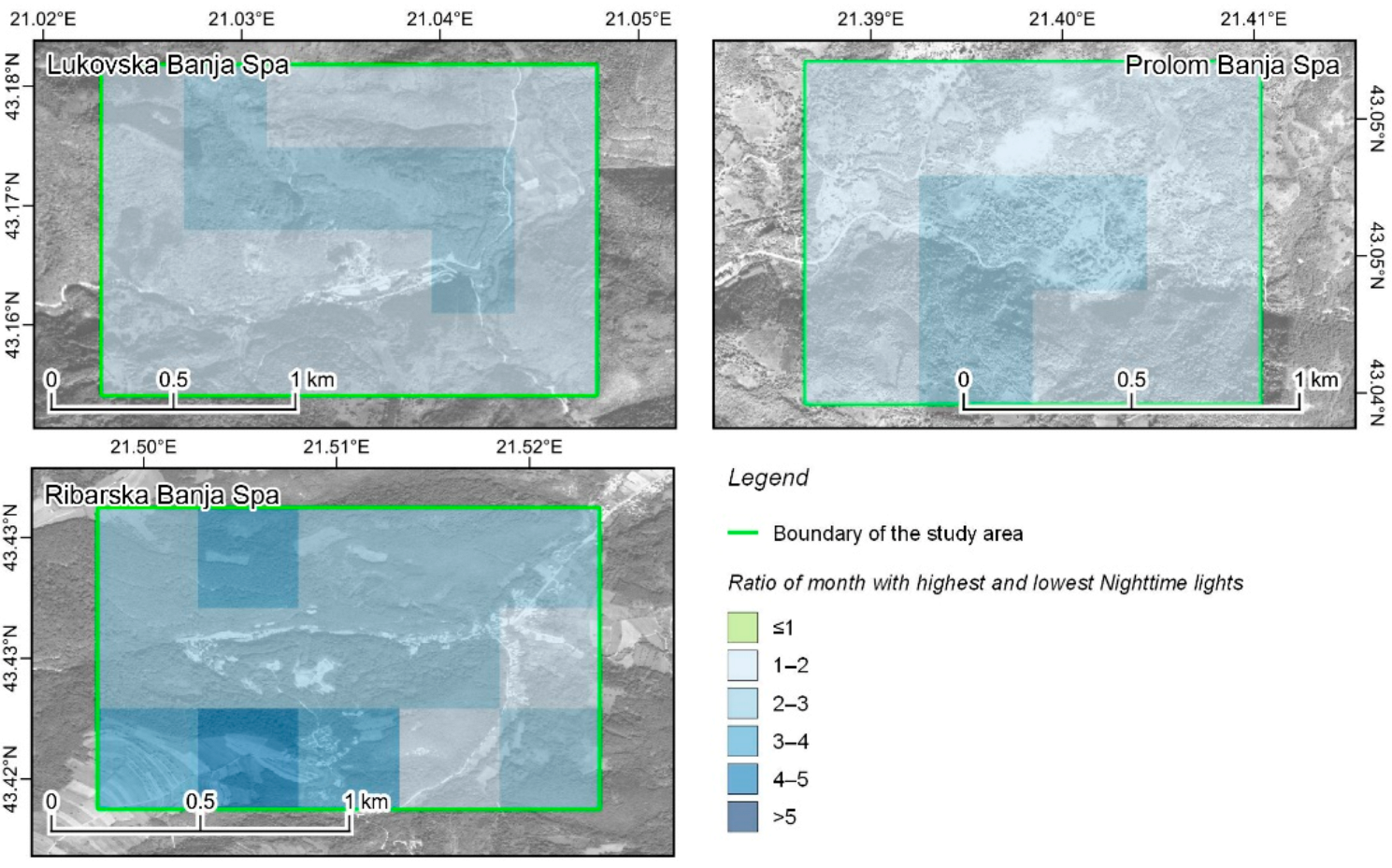

The seasonal character of spa centers is less pronounced. The peak also occurs in January, but slightly higher values of the seasonal coefficient are registered during the summer, which is related to the spa season in Serbia (Table 2). The most intense seasonality character expresses the Ribarska Banja spa resort. Generally speaking, in such places, the intensity of NTL is less intense (Figure 9). A somewhat more significant manifestation of the phenomenon in the spatial sense can be related to Prolom Banja spa, while the other two are more of a local character.

Figure 9. Average monthly NTL (2015–2019) for the selected spa centers.

On the other hand, observing the relation between the months with the highest and lowest radians in the observed period, it is clear that Ribarska Banja spa has the most pronounced seasonal character, as shown by the values of the Scos seasonality coefficient. In the other two spa centers, seasonal activity is observed along the access roads, which indicates an increase in activity and the influx of seasonal population, given that private accommodation facilities are located in these accessible zones (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Ratio of months with highest and lowest NTL for the selected spa centers.

2. Current Insights

In this research, an innovative approach based on satellite images of NTL was used, as an additional proxy for detecting seasonally activated rural areas. The obtained results showed that the cause of the most intensive seasonal movement of the population, i.e., seasonal activation of rural areas, is predominantly the tourist activity. Considering that mountainous rural areas with peripheral geographical position were identified as attractive for seasonal use (Figure 1), the role of tourism proved to be important in awakening the corpus of non-agricultural rural activities to maintain the vitality of these areas. This is in accordance with the postmodern tendencies that the development of rural areas should not be based only on agriculture, but also on other non-agricultural activities, primarily on tourism and recreation, as well as information and technology skills and services [6]. It implies the whole range of activities that integrated development of the area through common actions with other factors, such as good village infrastructure amenities, sustainable organization of public facilities and services, diversified rural economy, etc.

The concept of “new rural economy”, expressed through the model of multifunctionality, is based on providing new services by rural communities, primarily in the field of tourism and recreation [7]. This has both positive and negative implications, especially in the context of tourism seasonality. Tourism contributes to employment growth, but mainly it is seasonal or part-time work [8][9][10], which means a disproportion in employment demand [11]. During the peak season, employment is growing, absorbing the seasonal labour not just from the local community, but elsewhere, which could be a major problem, while in the off-peak season, it is the opposite situation [11]. Economic implications are related to low income during the off-peak periods and survival opportunities, which BarOn [12] called “seasonal loss”. Environmental implications are most pronounced during the peak season as a consequence of tourist concentration and the potential utilization and endangerment of fragile environments [11][13].

Current rural development in Serbia is defined as one of the main economic priorities [14], where rural tourism has an important role. Likewise, in tourism legislation, it is recognized as the most important for overall tourism development, as well as the most comprehensive solution for most tourist destinations in Serbia [15]. However, inherited conditions from previous decades contributed to low competitiveness of rural tourism in the international travel market [14]. Modern development of rural areas strives toward rural economy diversification and new context of rural areas [16][17][15].

In Serbia, most pronounced seasonal variations in activating the studied rural areas are related to winter tourism, excursion, and transit tourism. Likewise, the authors’ assumption is that second-home tourism in the form of private accommodation services occurs in seasonally activated areas, but with fewer pronounced changes. This is not visible due to the lack of official data and surveys, which is similar to the situation occurring in other countries as well, where data collected from hotels and other official registered facilities are considered as being most reliable and comparable due to the required register of each guest [18].

Obtained results indicated different seasonality types of the rural areas in Serbia, which is directly related to the scope of the tourist offer and duration of the tourist season. The general conclusion is that registered seasonality fluctuation, in the territory of Serbia, is low to moderate, pronounced only in several tourist areas that attract massive tourist movements. This conclusion is confirmed with results obtained in other seasonality research of tourism seasonality in Serbia, regardless of different applied methods [19][20].

On the other hand, a wider picture that implies comparison with the results from the neighboring countries showed a similar seasonality pattern—low overall seasonality (e.g., Macedonia [21]; however, with high seasonal activation concentrated in particular areas, such as coastal area in Croatia [22], spa centers in urban areas in Hungary [23], and spa centers with an extended tourist season in Romania [24].

In Serbia, the longest seasonal activation was detected in mountainous areas, characterized by mass tourist visits, such as with Kopaonik Mt., the largest mountain and ski destination. The most intensive seasonality in mountainous areas is registered during the winter season. In this group, there are areas with limited and less pronounced touristic offerings, but with obvious growing tendency in certain months (Stara planina Mt., Goč Mt., Golija Mt., Zlatar Mt., Tara Mt., Dukat Mt., Divčibare Mt., etc.). Areas with a less pronounced or shorter active period during the year are heterogeneous, but in the function of tourist activity, as well. Apart from winter peaks in the wider mountain area, which is associated with highly active mountain ski centers, seasonality occurs in some areas during the spring, and in the summer months, as well, however, less pronounced. Such winter tourist centers developed dual peak seasons; besides the winter snow season, an additional spring–summer season has emerged due to the promotion of mountain nature and sport activity holidays [22][19]. This season provides more diverse tourism opportunities and could represent a higher potential compared to the winter season [25].

Areas with lower seasonality, in terms of activating rural areas during the year, were registered, as well. It is expressed in less attractive tourist places, which refer mainly to spa centers with specialized tourist offerings and traffic accessibility, or smaller mountain areas (Rudnik Mt., Mokra Gora) and lakes (Zlatar Lake, Vlasina Lake, Bela Crkva Lake, etc.), natural reserves (Uvac River, Jerma River), and some transit and agricultural areas. This group has the characteristic low spring–summer seasonality, which caused their mainly local character. This is associated with a highly pronounced tourism summer trend that is oriented toward seaside destinations (Greece, Montenegro, Croatia, Turkey, etc.). The analysis of the selected spa centers confirmed the assumptions that specialised offers attract a mostly targeted group of tourists in a specific time of the season (health tourism, spa, and wellness) and remain with local character. Other studies highlight the conclusion that spa centers in Serbia still do not have a high degree of seasonal concentration of tourists [20], however, with a noticed prolonged spring–summer season between May and November [24].

As an addition to the examples of areas with high and low seasonality, the Zlatibor Mt. is distinguished with completely different results, which indicates a balanced annual tourist fluctuation. Zlatibor Mt. has diverse tourist offerings that attract massive tourist movements during the whole year, which enable the transformation of this mountain into a leading tourist center in Serbia. The summer season has a wide offering and accordingly great visit rate [24], as well as its reputation as a business and conference center [26][27]. During the winter season, Zlatibor has characteristics of a smaller ski center, which depends on climatic conditions, but it also has a wide range of other opportunities and tourist activities.

The spread of the seasonality phenomenon from the seasonal “epicenter” could be observed not only in a spatial aspect, towards awakening the surrounding settlements, but also from the aspect of diversified offerings, which affect the causes and character of seasonality during the year. The first aspect is especially pronounced in the mountainous areas such as Kopaonik Mt. and Zlatibor Mt., as well as the Stara planina Mt. Their tourism development has caused the expansion of accommodation capacities, and creation of a more diverse offer and services, fostering construction and use of infrastructure. Based on results of aforementioned case studies, spatial extension of rural area activation has been noticed during the year. Two models have been identified: (1) gradual extension of activity during the peak season in a wider mountain area toward the access roads and in the area of weekend settlements, which presents seasonally secondary tourist sites; (2) polycentric spatial development of tourist sites during the season peak, but with lower intensity. These models of seasonal activation are related to the housing pattern and accommodation units. High activity of central parts is related to the hotel complexes and good infrastructural equipment that are remarkable for valorised mountain areas (Kopaonik Mt., Stara planina Mt., and Zlatibor Mt.). On the other hand, polycentricity and diverse seasonal activation of smaller mountain areas are related to the traditional construction of second-homes that are occasionally used by non-residents. The second aspect is related to the tendency to extend the tourist season through activity diversification in order to answer the demands and preferences of a wider group of tourists [28]. Mountains with lower altitudes (Divčibare Mt., Goč Mt., Zlatar Mt.) show a more pronounced spring and summer peak, due to various factors: climate conditions (less share of snow), better infrastructure accessibility, vicinity of larger urban centers, traditional second-home tourism, etc. On the other hand, areas such as Kopaonik Mt. and Stara planina Mt. are characterized by peripheral geographical position, traffic isolation, extreme rurality, and better climate conditions, which induce monofunctional orientation toward winter tourism (ski resorts) with new tendencies of widening touristic offerings (hiking, camping, mountain biking, trekking, excursions, conferences, gastronomy, etc.) [19][29].

As well as the above-mentioned characteristics and spatial and temporal patterns in Serbia, it is obvious that seasonality driving factors are not natural conditions (climatic and environmental factors), tourist offerings and development of tourist centers, nor accommodations and infrastructure. As Ferrante et al. [18] highlighted, the main driving factors of seasonality are institutional (school and work timetable) and socio-cultural factors. However, in tourist centers that are narrowly specialised for certain activities or attract certain population groups, e.g., middle-aged people and elderly, the driving factors could be changed.

The possible expansion of seasonality research provides a variety of opportunities with different research objectives. It could be an in-depth study of hidden elements and structures within seasonality in tourism that cannot be detected by the methods used, traditional or alternative, to determine daily population movements and their activities or tourists in private accommodation, as well as seasonal labor, or other subjects of rural areas activation, as well as determination of their importance. On the other hand, as environmental pressure is already specified as an important stressor in rural areas during seasonality peak, it would be of great importance to identify and measure it, especially for tourist mountainous areas in Serbia, where seasonality is recognized as a large problem. One of the limitations of the used model is related to its application in rural areas. The applied method has limited capability to identify and monitor movement variety, such as daily circulation. For that reason, some authors suggest additional methods to complement results obtained by remote sensing, such as social sensing [30], people-centric sensing [31], urban sensing, or VGI for geographical data [2][32]. Comprehensive analysis based on intertwined results of different methods could provide deeper insight into the phenomenon of seasonality in order to better understand it and mitigate it.

Seasonal activation of rural areas is a phenomenon that tackles a wide area of legislative and strategic framework. It should be observed through the various spheres of social, economic, and spatial development, as well as at different government levels [15]. The rural issue, in the Serbian legal and planning framework, is conceptualised with the National Strategy for Rural Development and Agriculture and the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia in order to support competitiveness and encourage integral and balanced spatial development. The phenomenon of seasonality in aforementioned documents is observed through the seasonality in agricultural production, on one hand; and the seasonal settling pattern reflected by the occasional use of residential and economic facilities in rural areas, on the other. The economic aspect of the seasonality is more pronounced in the segment of tourism development (Master Plan for Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism, Strategy for Tourism Development), labour market, and sustainable development (National Sustainable Development Strategy). It is focused on balancing income during the year, occupancy rate of the accommodation, employment and seasonal labor market, performance of hospitality firms, balancing of infrastructure utilization, prolongation of the stay, encouraging activation of the off-season, diversity of tourist offerings, destination choice, etc. [13][20]. The seasonality predictability allows policy-makers, businesses, lenders, and investors to anticipate and minimize its impacts [22].

In this regard, the seasonality policy implications could be treated dually—positive and negative ones. Positive implications could be observed within general spatial development of rural areas, mitigation of the depopulation process, encouraging vulnerable group participation (women, elderly, etc.), achieving economic vitality, and social inclusion [19][33]. However, the negative impact of seasonality is emphasised. It is reflected through economic factors (employment, capacity utilisation, entrepreneurship success, etc.) related mostly to the off-peak season, [11][12]; environmental and social impacts (increased pressure, wildlife disturbance, pollution) during the peak season [11]. In that sense, although seasonality and its effects can be both positive and negative, it must be approached comprehensively through different levels of the legislative and planning framework. Strategy implementation and the spreading of tourism, activating the off-season period, and developing a more effective counter-season depends on involvement of the public and private sector, DMOs, policy-makers and their partnerships, as well as it should be treated in strategic documents [18].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14031604

References

- Čerović, S.; Knežević, M.; Sekulović, N.; Barjaktarević, B.; Đoković, F. The impact of economic crisis and non-economic factors on the tourism industry in Zlatibor. Eur. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 12, 1–9.

- Devkota, B.; Miyazaki, H.; Witayangkurn, A.; Kim, S.M. Using volunteered geographic information and nighttime light remote sensing data to identify tourism areas of interest. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4718.

- SORS. Tourist Turnover—September 2021; Statistical Release 2021; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021; 287, p. LXXI. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2021/Pdf/G20211287.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Sherbinin, A.; Balk, D.; Yager, K.; Jaiteh, M.; Poyyi, F.; Giri, C.; Wannebo, A. Social science applications of remote sensing. In A CIESIN Thematic Guide; Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Available online: https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/binaries/web/sedac/thematic-guides/tg.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Checa, J.; Nel, O. Urban intensities. The urbanization of the iberian mediterranean coast in the light of nighttime satellite images of the earth. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 115.

- Bollman, R.D. Agricultural Statistics for Rural Development; Agriculture and Rural Working Paper Series, No.49; Statistics: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001.

- Apedaile, L.P. The new rural economy. In Building for Success: Exploration of Rural Community and Rural Development; Halseth, G., Halseth, R., Eds.; Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation, Mount Allison University: Sackville, NB, Canada, 2004; pp. 111–134.

- Lopez-Sanz, J.M.; Panelas-Leguia, A.; Gotierrez-Rodriguez, P.; Cuesta-Vallino, P. Sustainable development and rural tourism in depopulated areas. Land 2021, 10, 985.

- Bontron, J.C.; Lasnier, N. Tourism: A potential source of rural employment. In Rural Employment: An International Perspective; Bollman, R.D., Bryden, J.M., Eds.; CAB International: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 427–446.

- Lopez-Sanz, J.M.; Panelas-Leguia, A.; Gotierrez-Rodriguez, P.; Cuesta-Vallino, P. Rural tourism and the sustainable development goals. a study of the variables that most influence the behavior of the tourist. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722973.

- Chung, J.Y. Seasonality in tourism: A review. e-Rev. Tour. Res. 2009, 7, 82–96.

- Baron, R.R.V. Seasonality in Tourism: A Guide to the Analysis of Seasonality and Trends for Policy Making; Economist Intelligence Unit: London, UK, 1975.

- Butler, R. Seasonality in tourism: Issues and problems. In Tourism: The State of Art; Seaton, A.V., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1994; pp. 332–339.

- Petrović, D.M.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T.; Darko, B.; Vuković, B.D.; Radovanović, M.; Jovanović, M.J.; Vuković, N. Tourism as an approach to sustainable rural development in post-socialist countries: A comparative study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 54.

- Radović, G. Underdevelopment of rural tourism in Serbia: Causes, consequences and possible directions of development. Econ. Agric. 2020, 67, 1337–1352.

- Drobnjaković, M. Development Role of the Rural Settlements in Central Serbia; Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019.

- Bogdanov, N. Small Rural Households in Serbia and Rural Non-Agricultural Economy; UNDP: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007; ISBN 978-86-7728-075-8.

- Ferrante, M.; Lo Magno, L.G.; De Cantis, S. Measuring tourism seasonality across European countries. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 220–235.

- Bratić, M.; Lesjak, M.; Đorđević, M.; Đorđević, M.; Radivojević, M. Seasonal movements in mountain tourism of Serbia: A review of methods and literature. Serb. J. Geosci. 2019, 5, 13–20.

- Pavlović, S.; Todorović, N.; Bolović, J.; Vesić, M. Variations in seasonality in spa centres of Serbia. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2021, 101, 89–110.

- Petrevska, B. Empirical analysis of seasonality patterns in tourism. J. Process Manag. New Technol. 2013, 1, 87–95.

- Corluka, G. Tourism seasonality—An overview. J. Bus. Paradig. 2019, 4, 21–43.

- Marton, G.; Hinek, M.; Kiss, R.; Csapo, J. Measuring seasonality at the major spa towns of Hungary. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2019, 68, 391–403.

- Stupariu, M.; Morar, C. Tourism seasonality in the spas of Romania. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2018, 22, 573–584.

- Dimić, M.; Radivojević, A. The complexity of the tourism product as a factor in the competitiveness of mountain destinations in Serbia. In Tourism in Function of Development of the Republic of Serbia; Cvijanović, D., Ružić, P., Andreeski, C., Gnjatović, D., Stanišić, T., Eds.; Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism, University of Kragujevac: Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia, 2017; pp. 327–342. Available online: http://www.tisc.rs/proceedings/index.php/hitmc/issue/view/4/The%20Second%20International%20Scientific%20Conference%2C%20TOURISM%20IN%20FUNCTION%20OF%20DEVELOPMENT%20OF%20THE%20REPUBLIC%20OF%20SERBIA%20-%20%D0%A2ourism%20product%20as%20a%20factor%20of%20competitiveness%20of%20the%20Serbian%20economy%20and%20experiences%20of%20other%20countries%2C%20Thematic%20Proceedings%20I (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Pavluković, V.; Vuković, S.; Cimbaljević, M. Determining Success factors for business tourism destinations: Evidence from Zlatibor (Serbia). Turizam 2021, 25, 110–120.

- Paunovic, I.; Radojevic, M. Towards green economy: Balancing market and seasonality of demand indicators in Serbian mountain tourism product development. In Trends in Tourism and Hospitality Industry; Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatia, University of Rijeka: Rijeka, Croatia, 2014; pp. 601–615. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/12415736/TOWARDS_GREEN_ECONOMY_BALANCING_MARKET_AND_SEASONALITY_OF_DEMAND_INDICATORS_IN_SERBIAN_MOUNTAIN_TOURISM_PRODUCT_DEVELOPMENT (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011.

- Mijatov, M.; Ivkov-Džigurski, A.; Pivac, T.; Košić, K. The leisure time aspects in ski centre—Kopaonik mountain case study (Serbia). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2016, 66, 291–306.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, S.; Gong, L.; Kang, C.; Zhi, Y.; Chi, G.; Shi, L. Social sensing: A new approach to understanding our socioeconomic environments. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2015, 105, 512–530.

- Campbell, A.T.; Eisenman, S.B.; Lane, N.D.; Miluzzo, E.; Peterson, R.A.; Lu, H.; Zheng, X.; Musolesi, M.; Fodor, K.; Ahn, G.-S. The rise of people centric sensing. IEEE Internet Comput. 2008, 12, 12–21.

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221.

- Remote Detection of (De)population Processes in Serbia. Available online: https://depopulacija.rs/ (accessed on 30 December 2021).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!