Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

Timely palliative care is a systematic process to identify patients with high supportive care needs and to refer these individuals to specialist palliative care in a timely manner based on standardized referral criteria.

- delivery of health care

- health care quality

- access and evaluation

- implementation

1. Introduction

Patients with cancer encounter significant supportive care needs throughout the disease trajectory, starting from the time of diagnosis [1]. These supportive care needs fluctuate with time and may include physical, psychological, social, spiritual, informational and financial concerns, often overlapping with each other, compromising patients’ quality of life. The demand for supportive care services increases with an aging patient population who often have multiple comorbid diagnoses. Moreover, there is a heightened need for supportive care in the era of novel cancer therapeutics, as patients are living longer while experiencing more chronic symptoms and adverse effects [2][3].

Over the past few decades, multiple supportive care programs have evolved to address these growing patient care needs [1]. In particular, there has been substantial development in specialist palliative care teams that provide interdisciplinary, holistic care for patients with cancer and their families [4][5][6]. Multiple randomized controlled trials have found that compared to primary palliative care provided by oncologists, early referral to specialist palliative care can improve patients’ quality of life, symptom control, mood, illness understanding, end-of-life care and survival [7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. Meta-analyses over the past 5 years have consistently reported the benefits associated with specialist palliative care [14][15][16][17][18] (Table 1). To date, the evidence on primary palliative care remains limited [19][20][21]. Thus, the focus of this article is on delivery of timely specialist palliative care.

Table 1. Meta-analyses on the outcomes of specialist palliative care for patients with cancer.

| Setting | No. of Studies | No. of Patients | Quality of Life SMD (95% CI) |

Symptoms SMD (95% CI) |

Mood SMD (95% CI) |

Survival HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kavalieratos et al. 2016 [16] | IP/OP | 11 | 1670 | 0.12 (−0.2, 0.27) |

−0.14 (−0.39, 0.10) |

0.82 (0.60, 1.13) | |

| Gartner et al. 2017 [14] | IP/OP | 5 | 828 | 0.20 (0.01, 0.38) |

−0.21 (−1.35, 0.94) |

||

| OP (early only) | 2 | 388 | 0.33 (0.05, 0.61) |

||||

| Haun et al. 2017 [15] | OP | 7 | 1614 | 0.27 (0.15, 0.38) |

−0.23 (−0.35, −0.10) |

−0.11 (−0.26, 0.03) |

0.85 (0.56, 1.28) |

| Heorger et al. 2019 [17] | OP | 8 | 2092 | 0.18 (0.09, 0.28) |

1y: 14.1% (6.5%, 21.7%) |

||

| Fulton et al. 2019 [18] | OP | 10 | 2385 | 0.24 (0.13, 0.35) |

−0.17 (−0.45, 0.11) |

−0.09 (−0.32, 0.13) |

0.84 (0.61, 1.18) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IP, inpatient; OP, outpatient; SMD, standardized mean difference.

2. What Is Timely Palliative Care?

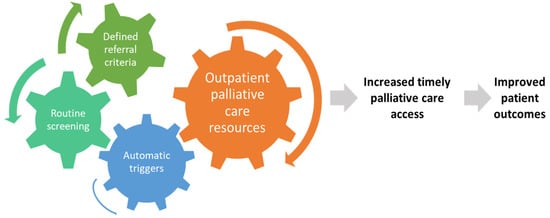

Timely palliative care is a systematic process to identify patients with high supportive care needs and to refer these individuals to specialist palliative care in a timely manner based on standardized referral criteria [22]. It requires four components: (1) routine screening of supportive care needs at the oncology clinics, (2) establishment of institution-specific consensual criteria for referral, (3) having a system in place to trigger a referral when patients meet criteria, and (4) availability of outpatient palliative care resources to provide timely access (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model for timely palliative care. Timely palliative care has four key components: routine systematic screening, a defined set of referral criteria, a mechanism to trigger referral for appropriate patients, and an adequately staffed outpatient specialist palliative care clinic. The expected outcome is a greater number of patients receiving specialist palliative care and earlier timing of referral, which would lead to improved patient outcomes such as quality of life, quality of end-of-life care, and possibly survival.

3. How Is Timely Palliative Care Different from Early Palliative Care?

The concept of early palliative care is exemplified in the landmark Temel trial, in which patients with metastatic lung cancer were referred to palliative care within 2 months of diagnosis [23]. Although what constitutes “early” has not been established, randomized trials on early palliative care typically involved patients within 2–3 months of diagnosis of advanced diseases and had an ECOG performance status of 2 or less [7][9][10][11][24][25][26][27]. Patients referred within this timeframe are typically considered to have early palliative care involvement. Of note, patients did not need to have supportive care needs to qualify for a palliative care referral in these trials. However, a recent secondary analysis of the Zimmermann trial found that patients with higher symptom burden at baseline were more likely to derive a benefit from the palliative care intervention [28].

Due to the scarcity of palliative care resources, it is not possible to provide early palliative care for all patients with advanced disease from around the time of diagnosis [29]. Moreover, some patients may not require specialist palliative care initially due to low supportive care needs or their needs have been adequately addressed by the oncology team. In contrast to early palliative care, which initiates referral based on disease trajectory, timely palliative care is referral based on needs. Similar to early palliative care, timely palliative care is often initiated in the outpatient setting and provided to a majority of patients early in the disease trajectory.

Timely palliative care is early palliative care personalized around patients’ needs and delivered at the optimal time and setting [4]. Similar to the concept of targeted therapy, oncologists may only offer treatment for selected patients with “targetable mutations” instead of treating all patients. This approach provides a more rational use of resources, minimizes unnecessary exposure to those who may be less likely to benefit, and maximizes the impact on patients offered the intervention [28].

4. Rationale for Timely Palliative Care

Although specialist palliative care teams have significant expertise managing complex symptom crises that often occur in the last months of life, palliative care interventions are best provided proactively to prevent suffering [30][22]. Optimal timing is especially important as it allows specialist palliative care teams to more effectively introduce symptom management, provide psychological support and facilitate care planning. At MD Anderson Cancer Center, the median time from outpatient palliative care referral to death is over 12 months [31]. This allows the palliative care team to have multiple visits with patients and provide comprehensive care longitudinally.

Palliative care teams can provide a variety of non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic measures to alleviate symptoms such as pain, dyspnea and nausea when they first present. Subsequent visits can allow the palliative care team to optimize symptom control by providing therapeutic trials, active titration, proper education, longitudinal monitoring, and reinforcement of treatment adherence [32][33]. Successful symptom management not only improves quality of life, but also prevents escalation of symptoms leading to avoidable emergency room visits and hospitalizations [34][35]. Optimization of physical symptoms such as fatigue and anorexia–cachexia may also allow patients to better tolerate cancer treatments. Indeed, a higher baseline quality of life is associated with improved overall survival and progression-free survival for patients undergoing chemotherapy [36][37].

In addition to physical symptoms, timely palliative care referral allows for optimal psychological care to be delivered over time. It takes time for the palliative care team to establish trust, rapport, and explore the layers of emotional and existential concerns. Acute issues (e.g., severe pain, delirium) often need to be addressed first before chronic psychological issues can be managed. Moreover, many evidence-based interventions to treat depression and anxiety, such as counseling and exercises, require weeks and months to take effect [38][39]. In addition to patients, family caregivers benefit from building longitudinal relationships with the palliative care team so they can receive the proper education, psychologic care and resources to better support the patients throughout the disease trajectory [40][41].

Similar to symptom management and psychosocial care, serious illness conversations should start well before the last months of life because patients often require time to digest prognostic information and actively prepare for the future [42][43][44]. Palliative care teams have specialized training in communication skills to facilitate discussions around sensitive subjects such as prognostic disclosures, goals-of-care conversations and advance care planning. These discussions are longitudinal by nature and need to be timed carefully. Decisions regarding end-of-life care initiated by an oncology team are best followed by an interdisciplinary team to optimize goal-concordant care. Studies have found that early palliative care not only improves illness understanding, but also quality of end-of-life care by reducing chemotherapy use, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, intensive care units admissions in the last month of life [10][45].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14041047

References

- Hui, D.; Hoge, G.; Bruera, E. Models of supportive care in oncology. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2021, 33, 259–266.

- Mo, L.; Urbauer, D.L.; Bruera, E.; Hui, D. Recommendations for supportive care and best supportive care in NCCN clinical practice guidelines for treatment of cancer: Differences between solid tumor and hematologic malignancy guidelines. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7385–7392.

- Mo, L.; Urbauer, D.L.; Bruera, E.; Hui, D. Recommendations for Palliative and Hospice Care in NCCN Guidelines for Treatment of Cancer. Oncologist 2021, 26, 77–83.

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Models of Palliative Care Delivery for Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 852–865.

- Davis, M.P.; Bruera, E.; Morganstern, D. Early integration of palliative and supportive care in the cancer continuum. In Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting 2013, Chicago, IL, USA, 31 May–4 June 2013.

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; Aapro, M.; Albreht, T.; Anderson, R.; Bruera, E.; Brunelli, C.; Caraceni, A.; Cervantes, A.; Currow, D.C.; et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e588–e653.

- Bakitas, M.; Lyons, K.D.; Hegel, M.T.; Balan, S.; Brokaw, F.C.; Seville, J.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Tosteson, T.D.; Byock, I.R.; et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 741–749.

- Bakitas, M.; Tosteson, T.; Li, Z.; Lyons, K.; Hull, J.; Li, Z.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Hegel, M.; et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1438–1445.

- Maltoni, M.; Scarpi, E.; Dall’Agata, M.; Schiavon, S.; Biasini, C.; Codeca, C.; Broglia, C.M.; Sansoni, E.; Bortolussi, R.; Garetto, F.; et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: A randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 69, 110–118.

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Admane, S.; Gallagher, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Lynch, T.J.; Lennes, I.T.; Dahlin, C.M.; Pirl, W.F. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2319–2326.

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Pirl, W.F.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Back, A.L.; Kamdar, M.; Jacobsen, J.; Chittenden, E.H.; et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care in Patients with Lung and GI Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 35, 834–841.

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730.

- Davis, M.P.; Temel, J.S.; Balboni, T.; Glare, P. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2015, 4, 99–121.

- Gaertner, J.; Siemens, W.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Antes, G.; Meffert, C.; Xander, C.; Stock, S.; Mueller, D.; Schwarzer, G.; Becker, G. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017, 357, j2925.

- Haun, M.W.; Estel, S.; Rucker, G.; Friederich, H.C.; Villalobos, M.; Thomas, M.; Hartmann, M. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD011129.

- Kavalieratos, D.; Corbelli, J.; Zhang, D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Hanmer, J.; Hoydich, Z.P.; Ikejiani, D.Z.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2104–2114.

- Hoerger, M.; Wayser, G.R.; Schwing, G.; Suzuki, A.; Perry, L.M. Impact of Interdisciplinary Outpatient Specialty Palliative Care on Survival and Quality of Life in Adults With Advanced Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 674–685.

- Fulton, J.J.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Cutson, T.M.; Porter Starr, K.N.; Kamal, A.; Ramos, K.; Freiermuth, C.E.; McDuffie, J.R.; Kosinski, A.; Adam, S.; et al. Integrated outpatient palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 123–134.

- McCorkle, R.; Jeon, S.; Ercolano, E.; Lazenby, M.; Reid, A.; Davies, M.; Viveiros, D.; Gettinger, S. An Advanced Practice Nurse Coordinated Multidisciplinary Intervention for Patients with Late-Stage Cancer: A Cluster Randomized Trial. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 962–969.

- Dyar, S.; Lesperance, M.; Shannon, R.; Sloan, J.; Colon-Otero, G. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: Results of a randomized pilot study. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 890–895.

- Schenker, Y.; Althouse, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.; White, D.B.; Chu, E.; Smith, K.J.; Resick, J.M.; Belin, S.; Park, S.Y.; Smith, T.J.; et al. Effect of an Oncology Nurse-Led Primary Palliative Care Intervention on Patients With Advanced Cancer: The CONNECT Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 1451–1460.

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Bruera, E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 356–376.

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742.

- Scarpi, E.; Dall’Agata, M.; Zagonel, V.; Gamucci, T.; Berte, R.; Sansoni, E.; Amaducci, E.; Broglia, C.M.; Alquati, S.; Garetto, F.; et al. Systematic vs. on-demand early palliative care in gastric cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial assessing patient and healthcare service outcomes. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2425–2434.

- Vanbutsele, G.; Pardon, K.; Van Belle, S.; Surmont, V.; De Laat, M.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Cocquyt, V.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 394–404.

- Temel, J.S.; Sloan, J.; Zemla, T.; Greer, J.A.; Jackson, V.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Kamdar, M.; Kamal, A.; Blinderman, C.D.; Strand, J.; et al. Multisite, Randomized Trial of Early Integrated Palliative and Oncology Care in Patients with Advanced Lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer: Alliance A221303. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 922–929.

- Franciosi, V.; Maglietta, G.; Degli Esposti, C.; Caruso, G.; Cavanna, L.; Bertè, R.; Bacchini, G.; Bocchi, L.; Piva, E.; Monfredo, M.; et al. Early palliative care and quality of life of advanced cancer patients-a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 8, 381–389.

- Rodin, R.; Swami, N.; Pope, A.; Hui, D.; Hannon, B.; Zimmermann, C. Impact of early palliative care according to baseline symptom severity: Secondary analysis of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Med. 2022.

- Schenker, Y.; Arnold, R. Toward Palliative Care for All Patients With Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1459–1460.

- Knaul, F.M.; Farmer, P.E.; Krakauer, E.L.; De Lima, L.; Bhadelia, A.; Jiang Kwete, X.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Gómez-Dantés, O.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Alleyne, G.A.O.; et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2018, 391, 1391–1454.

- Hui, D.; Anderson, L.; Tang, M.; Park, M.; Liu, D.; Bruera, E. Examination of referral criteria for outpatient palliative care among patients with advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 295–301.

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1640–1646.

- Hui, D.; Bohlke, K.; Bao, T.; Campbell, T.C.; Coyne, P.J.; Currow, D.C.; Gupta, A.; Leiser, A.L.; Mori, M.; Nava, S.; et al. Management of Dyspnea in Advanced Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1389–1411.

- Hui, D.; Kim, S.H.; Roquemore, J.; Dev, R.; Chisholm, G.; Bruera, E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014, 120, 1743–1749.

- Jang, R.W.; Krzyzanowska, M.K.; Zimmermann, C.; Taback, N.; Alibhai, S.M. Palliative care and the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, dju424.

- Cella, D.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Bushmakin, A.; Charbonneau, C.; Li, J.Z.; Kim, S.T.; Chen, I.; Michaelson, M.D.; Motzer, R.J. Quality of life predicts progression-free survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib versus interferon alfa. J. Oncol. Pract. 2009, 5, 66–70.

- Hui, D.; Darke, A.K.; Guthrie, K.A.; Subbiah, I.M.; Unger, J.M.; Hershman, D.L.; Krouse, R.S.; Bakitas, M.; O’Rourke, M.A. Association Between Health-Related Quality of Life and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of SWOG Clinical Trials. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021.

- Schmitz, K.H.; Campbell, A.M.; Stuiver, M.M.; Pinto, B.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Morris, G.S.; Ligibel, J.A.; Cheville, A.; Galvao, D.A.; Alfano, C.M.; et al. Exercise is medicine in oncology: Engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 468–484.

- Jacobsen, P.B.; Jim, H.S. Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: Achievements and challenges. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008, 58, 214–230.

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Azuero, A.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Tosteson, T.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Akyar, I.; et al. Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1446–1452.

- El-Jawahri, A.; Greer, J.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Back, A.L.; Kamdar, M.; Jacobsen, J.; Chittenden, E.H.; Rinaldi, S.P.; et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care on Caregivers of Patients with Lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1528–1534.

- Mack, J.W.; Cronin, A.; Keating, N.L.; Taback, N.; Huskamp, H.A.; Malin, J.L.; Earle, C.C.; Weeks, J.C. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4387–4395.

- Bernacki, R.E.; Block, S.D. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1994–2003.

- Wright, A.A.; Zhang, B.; Ray, A.; Mack, J.W.; Trice, E.; Balboni, T.; Mitchell, S.L.; Jackson, V.A.; Block, S.D.; Maciejewski, P.K.; et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008, 300, 1665–1673.

- Kassam, A.; Gupta, A.; Rapoport, A.; Srikanthan, A.; Sutradhar, R.; Luo, J.; Widger, K.; Wolfe, J.; Earle, C.; Gupta, S. Impact of Palliative Care Involvement on End-of-Life Care Patterns among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2506–2515.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!