Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Communication

The consumer–celebrity congruence moderated the indirect effect of consumer–brand congruence on brand preference and boycott recommendations, but not purchase intention. When brands practice CSA, consumer–brand congruence rather than consumer–celebrity congruence could play a more important role in shaping consumer behaviors.

- congruence

- corporate social advocacy (CSA)

- celebrity endorsement

1. Corporate Social Advocacy

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is generally defined as a company’s position and activities in relation to its perceived social duties, and is closely connected to brand activism, although there are important differences [1][2]. Under this umbrella exists the concept of corporate social advocacy (CSA). While the term “CSA” generally refers to a company’s public stance on socio-political issues [3], CSA has also been defined as a corporate action that may be carried out by any representative of the company in relation to partisan sociopolitical issues [4]. Some scholars have referred to corporate social advocacy (CSA) as corporate political advocacy or brand activism [5]. CSA can come in many forms, including CEO statements or speeches [6][7][8], official statements of a company [9][10][11][12], advertisements [13][14], and corporate social media posts [5][8][15].

More recently, researchers have begun to distinguish CSA from CSR [15][16]. Because CSA can often promote challenging beliefs and objectives, it is frequently distinguished from CSR, which entails charitable support for broadly popular projects [17]. Because the nature of the corporate support is different, CSR and CSA efforts generate distinctive consumer responses. While CSA often results in polarized reactions, CSR messages usually evoke support or general ambivalence from customers [2].

2. Consumer–Brand Congruence

A substantial body of literature has examined various instances of congruence that enhance consumers’ positive attitudes toward brands and influence positive behavioral intentions [18]. Congruence refers to the extent to which two or more objects share similar or important characteristics [19]. Identifying areas of congruence is important, as one’s identity can bolstered by finding and embracing an ideology (political or otherwise) that helps one to connect with others [20]. Highly congruent information combines with a person’s personal identity more so than incongruent information, encouraging highly congruent information to be viewed more favorably [21]. Studies also show that congruent information can produce more favorable attitudes and mitigate negative attitudes [22]. It has been well-documented that consumers tend to display positive attitudes toward a brand when they associate themselves with it, which is called consumer–brand congruence or consumer–brand identification [23].

The literature on consumer behavior based on congruence confirms that individuals select certain products or brands for their symbolic meanings and practical value [24][25][26][27]. People consider not only what they do with the product but also the meanings that are associated with them. Scholars refer to this cognitive match between a product or brand image and a consumer’s identity as self-image congruence or self-congruity [28][29][30][31], with research on the topic showing that it plays a significant role in motivating consumer behaviors [32][33][34].

Previous work shows that self-congruence between brands and consumers leads to positive consumer attitudes toward said brands [29][35], more effective advertising [36][37], increased purchase intention [38], and overall better brand preference [39][40], all of which are also affected by brand attitude [41]. According to a recent study on CSA, consumer–company congruence was positively associated with a consumer’s intention to purchase from companies practicing CSA, whereas consumer–company congruence was negatively associated with consumers’ boycott intention [42]. However, little is known about how an individual’s perceived congruence between themselves and a brand affects their attitude toward the brand as a reaction of brands taking a stand.

3. Consumers Intention and Preference

For scholars in the corporate communication and advertising fields, brand preference is often discussed in tandem with other measures such as brand satisfaction [43] and emotional attachment [44]. Brand satisfaction has been shown to function as a precursor to brand preference, meaning that consumer attitudes toward a brand should affect brand preference, either positively or negatively. Emotional attachment is influenced by self-congruence [45] and affects brand preference and purchase intent [46].

Brand activism provides consumers the opportunity to compare themselves to the identity of the brand within the context of moral judgments [47]. Consumer-brand identification postulates that consumers who strongly identify with a brand should have more favorable brand attitudes as well as stronger purchase intentions [38][48]. Hong and Li (2021) also found that brands that are vocal about socio-political issues will see an increase in purchase intention from consumers who hold similar viewpoints with the brand. Likewise, CSA plays a significant role in impacting brand preferences as it gives the consumer a way to have a voice, make a statement and exercise power. The products purchased, and by extension the preference of a particular brand, is a way for consumers to have agency, by sharing their views, values, beliefs, and lifestyles [49].

4. Boycotts and Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance theory, which some refer to as one of the consistency family theories, argues that some circumstances can motivate an individual to take actions that do not match their beliefs, which result in uncomfortable experiences and tension, leading the person to modify their beliefs [50]. Consumer–brand congruence is one of three constructs (along with brand–cause fit and consumer–cause fit) that interact with consistencies and inconsistencies in the minds of the consumers [9]. The focus of cognitive dissonance theory is on one’s self, which is in line with the construct of consumer–brand congruence, which deals with consumers’ identification of self-value [9][50].

In an investigation on consumer boycott behaviors, Klein et al. (2004) found that when consumers encounter an initial trigger event that generates negative attitudes, they subsequently evaluate the expected costs and benefits of a brand boycott. Consistent with other boycott literature [51][52], Klein et al. (2004) found that boycott participation is prompted by consumer beliefs that a brand has engaged in conduct that is wrong and could have negative consequences. Klein et al.’s (2004) study showed that the perceived egregiousness of the company’s action was a powerful predictor of boycott participation due to the formation of negative attitudes by consumers. This means that unexpected consumer reactions might occur as a result of brand activism [53]. Taking a stance might enrage consumers, partners, and workers who disagree with the company’s policies, which is why many businesses are afraid to do so [54][55]. This study hypothesizes that consumers may recommend boycotting as a way to show their socio-political opinion [42][56].

5. Brand Attitude

Consumer attitudes can generate both favorable and unfavorable beliefs about a brand [57]. Congruence can lead to more favorable attitudes and diminish negative attitudes [22], which results in higher purchase intentions [38], brand preferences [39][40], and a lower likelihood of boycott recommendations [58][59].

In a recent study on CSA, brand attitude mediates the relationship between consumer–brand socio-political position congruence and boycott intention, as well as purchase intention [42]. In line with these findings, earlier studies showed that when a brand and consumer have a shared position on a socio-political issue, consumers will have more favorable attitudes toward the brand and are more likely to purchase from the company; on the other hand, if consumers do not agree with the brand’s stance, consumers are more likely to hold negative attitudes toward the brand and attempt to boycott the brand [60][61]. Based on the literature, it is possible that brand attitude serves as a bridge between consumer–brand congruence and a consumer’s behavioral intentions.

6. Celebrity Endorsements

An extensive body of literature shows that celebrity endorsements lead to higher levels of consumer–brand patronage intentions [62]. Sports apparel brands choose athletes as celebrity endorsers to enhance positive attitudes and encourage merchandise sales [63][64]. In sports literature, studies show that consumers are more likely to display higher levels of purchase intention when they associate themselves with endorsed athletes [65][66]. Specifically, researchers found that companies could achieve a variety of benefits from athlete endorsements, such as a consumer’s increased probability of brand choice, intention to pay a premium price, and positive word of mouth [67][68].

However, when using controversial celebrity endorsements, research shows that these partnerships can yield negative outcomes such as negative publicity [69], negative word-of-mouth, and consumer boycotts [70]. These responses can lead to companies being required to take swift action. As example would be the ending of Kate Moss’ relationship with several fashion brands such as Burberry and H&M after reports surfaced that she had issues with substance abuse [71].

Pradhan, Duraipandian, and Sethi (2016) investigated the effect of celebrity–brand–user congruence on brand attitude and brand purchase intention. The authors suggested that future research should consider examining sports figures or movie stars as a factor that moderates the impact of personality congruence on brand attitude and purchase intention. Another relevant study examined the moderating effect of the attractiveness, experience, and similarity of an endorser on a consumer’s willingness to purchase a product [72]. The study found that consumers were more likely to purchase a product when the endorser’s credibility is moderated by the consumer’s similarity with the endorser.

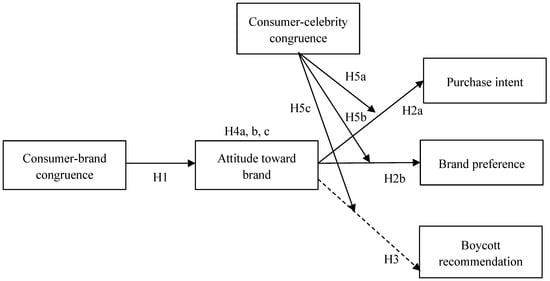

The Conceptual Model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model. Note. H4 = Indirect effects of consumer–brand congruence on purchase intent, brand preference, and boycott recommendation via attitude toward the brand. Dotted line represents a negative association.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14031811

References

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84.

- Hydock, C.; Paharia, N.; Blair, S. Should Your Brand Pick a Side? How Market Share Determines the Impact of Corporate Political Advocacy. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 57, 1135–1151.

- Dodd, M.D.; Supa, D.W. Conceptualizing and Measuring “Corporate Social Advocacy” Communication: Examining the Impact on Corporate Financial Performance. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 2–23.

- Bhagwat, Y.; Warren, N.L.; Beck, J.T.; Watson, G.F., IV. Corporate Sociopolitical Activism and Firm Value. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 1–21.

- Lim, J.S.; Young, C. Effects of Issue Ownership, Perceived Fit, and Authenticity in Corporate Social Advocacy on Corporate Reputation. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102071.

- Dodd, M.D.; Supa, D. Testing the Viability of Corporate Social Advocacy as a Predictor of Purchase Intention. Commun. Res. Rep. 2015, 32, 287–293.

- Chatterji, A.K.; Toffel, M.W. Assessing the Impact of CEO Activism. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 159–185.

- Lan, X.; Tarasevich, S.; Proverbs, P.; Myslik, B.; Kiousis, S. President Trump vs. CEOs: A Comparison of Presidential and Corporate Agenda Building. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 30–46.

- Hong, C.; Li, C. To Support or to Boycott: A Public Segmentation Model in Corporate Social Advocacy. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 160–177.

- Parcha, J.M.; Kingsley Westerman, C.Y. How Corporate Social Advocacy Affects Attitude Change Toward Controversial Social Issues. Manag. Commun. Q. 2020, 34, 350–383.

- Waymer, D.; Logan, N. Corporate Social Advocacy as Engagement: Nike’s Social Justice Communication. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102005.

- Yim, M.C. Fake, Faulty, and Authentic Stand-Taking: What Determines the Legitimacy of Corporate Social Advocacy? Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2021, 15, 60–76.

- Kim, J.K.; Overton, H.; Bhalla, N.; Li, J.-Y. Nike, Colin Kaepernick, and the Politicization of Sports: Examining Perceived Organizational Motives and Public Responses. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101856.

- Li, J.-Y.; Kim, J.K.; Alharbi, K. Exploring the Role of Issue Involvement and Brand Attachment in Shaping Consumer Response toward Corporate Social Advocacy (CSA) Initiatives: The Case of Nike’s Colin Kaepernick Campaign. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 1–25.

- Rim, H.; Lee, Y.; Yoo, S. Polarized Public Opinion Responding to Corporate Social Advocacy: Social Network Analysis of Boycotters and Advocators. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101869.

- Overton, H.; Kim, J.K.; Zhang, N.; Huang, S. Examining Consumer Attitudes toward CSR and CSA Messages. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102095.

- Hydock, C.; Paharia, N.; Weber, T.J. The Consumer Response to Corporate Political Advocacy: A Review and Future Directions. Cust. Needs Solut. 2019, 6, 76–83.

- Gupta, S.; Pirsch, J. The Company-cause-customer Fit Decision in Cause-related Marketing. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 314–326.

- Kulkarni, A.; Otnes, C.; Ruth, J.; White, T. The Role of Congruence Theory in Consumer Response to Business-To-Consumer Gift Giving. In Advances in Consumer Research; Lee, A.Y., Soman, D., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2008; Volume 35, p. 901.

- Flight, R.L.; Coker, K. Birds of a Feather: Brand Attachment through the Lens of Consumer Political Ideologies. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021. Ahead of printing.

- George, M. The Structure of Value: Accounting for Taste. In Affect and Cognition; Clark, M.S., Fiske, S.T., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 3–36. ISBN 978-1-315-80275-6.

- Moore, R.S.; Stammerjohan, C.A.; Coulter, R.A. Banner Advertiser-Web Site Context Congruity And Color Effects On Attention And Attitudes. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 71–84.

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24.

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168.

- Lee, D.; Hyman, M.R. Hedonic/Functional Congruity Between Stores and Private Label Brands. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2008, 16, 219–232.

- Leigh, J.H.; Gabel, T.G. Symbolic Interactionism: Its Effects on Consumer Behavior and Implications for Marketing Strategy. J. Consum. Mark. 1992, 9, 27–38.

- Solomon, M.R. The Role of Products as Social Stimuli: A Symbolic Interactionism Perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 319–329.

- Hosany, S.; Martin, D. Self-Image Congruence in Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 685–691.

- Sirgy, M.J.; Grewal, D.; Mangleburg, T.F.; Park, J.-O.; Chon, K.-S.; Claiborne, C.B.; Johar, J.S.; Berkman, H. Assessing the Predictive Validity of Two Methods of Measuring Self-Image Congruence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 229–241.

- Sirgy, M.J.; Grewal, D.; Mangleburg, T. Retail Environment, Self-Congruity, and Retail Patronage. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 127–138.

- Sirgy, M.J.; Su, C. Destination Image, Self-Congruity, and Travel Behavior: Toward an Integrative Model. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 340–352.

- Kressmann, F.; Sirgy, M.J.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F.; Huber, S.; Lee, D.-J. Direct and Indirect Effects of Self-Image Congruence on Brand Loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 955–964.

- Sirgy, M.J.; Samli, A.C. A Path Analytic Model of Store Loyalty Involving Self-Concept, Store Image, Geographic Loyalty, and Socioeconomic Status. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1985, 13, 265–291.

- Sirgy, M.J.; Johar, J.S.; Samli, A.C.; Claiborne, C.B. Self-Congruity versus Functional Congruity: Predictors of Consumer Behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1991, 19, 363–375.

- Ekinci, Y.; Riley, M. An Investigation of Self-Concept: Actual and Ideal Self-Congruence Compared in the Context of Service Evaluation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 201–214.

- Bjerke, R.; Polegato, R. How Well Do Advertising Images of Health and Beauty Travel across Cultures? A Self-Concept Perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 865–884.

- Hong, J.W.; Zinkhan, G.M. Self-Concept and Advertising Effectiveness: The Influence of Congruency, Conspicuousness, and Response Mode. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 53–77.

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88.

- Branaghan, R.J.; Hildebrand, E.A. Brand Personality, Self-Congruity, and Preference: A Knowledge Structures Approach. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 304–312.

- Jamal, A.; Al-Marri, M. Exploring the Effect of Self-Image Congruence and Brand Preference on Satisfaction: The Role of Expertise. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 613–629.

- Bass, F.M.; Talarzyk, W.W. An Attitude Model for the Study of Brand Preference. J. Mark. Res. 1972, 9, 93–96.

- Hong, C.; Li, C. Will Consumers Silence Themselves When Brands Speak up about Sociopolitical Issues? Applying the Spiral of Silence Theory to Consumer Boycott and Buycott Behaviors. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2021, 33, 193–211.

- Jamal, A.; Goode, M.M.H. Consumers and Brands: A Study of the Impact of Self-image Congruence on Brand Preference and Satisfaction. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2001, 19, 482–492.

- Malär, L.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D.; Nyffenegger, B. Emotional Brand Attachment and Brand Personality: The Relative Importance of the Actual and the Ideal Self. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 35–52.

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300.

- Grisaffe, D.B.; Nguyen, H.P. Antecedents of Emotional Attachment to Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1052–1059.

- Mukherjee, S.; Althuizen, N. Brand Activism: Does Courting Controversy Help or Hurt a Brand? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 772–788.

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.; Ratneshwar, S.; Sen, S. Drivers of Consumer-Brand Identification. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 406–418.

- Eyada, B. Brand Activism, the Relation and Impact on Consumer Perception: A Case Study on Nike Advertising. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2020, 12, 30–42.

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford Redwood City, CA, USA, 1957; ISBN 978-0-8047-0911-8.

- Friedman, M. Consumer Boycotts: Effecting Change through the Marketplace and Media; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999.

- Smith, N.C.; Cooper-Martin, E. Ethics and Target Marketing: The Role of Product Harm and Consumer Vulnerability. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 1–20.

- Korschun, D.; Martin, K.D.; Vadakkepatt, G. Marketing’s Role in Understanding Political Activity. J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 39, 378–387.

- Klostermann, J.; Hydock, C.; Decker, R. The Effect of Corporate Political Advocacy on Brand Perception: An Event Study Analysis. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021. Ahead of printing.

- Moorman, C. Commentary: Brand Activism in a Political World. J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 39, 388–392.

- Makarem, S.C.; Jae, H. Consumer Boycott Behavior: An Exploratory Analysis of Twitter Feeds. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 50, 193–223.

- Phelps, J.E.; Hoy, M.G. The Aad-Ab-PI Relationship in Children: The Impact of Brand Familiarity and Measurement Timing. Psychol. Mark. 1996, 13, 77–105.

- Chiu, H.-K. Exploring the Factors Affecting Consumer Boycott Behavior in Taiwan: Food Oil Incidents and the Resulting Crisis of Brand Trust. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2016, 11, 49–66.

- Klein, J.G.; Smith, N.C.; John, A. Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 92–109.

- Baek, Y.M. To Buy or Not to Buy: Who Are Political Consumers? What Do They Think and How Do They Participate? Polit. Stud. 2010, 58, 1065–1086.

- Swimberghe, K.; Flurry, L.A.; Parker, J.M. Consumer Religiosity: Consequences for Consumer Activism in the United States. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 453–467.

- Carlson, B.D.; Donavan, T. Concerning the Effect of Athlete Endorsements on Brand and Team-Related Intentions. Sport Mark. Q. 2008, 17, 154–162.

- Bush, A.J.; Martin, C.A.; Bush, V.D. Sports Celebrity Influence on the Behavioral Intentions of Generation Y. J. Advert. Res. 2004, 44, 108–118.

- Mullin, B.J.; Hardy, S.; Sutton, W.A. Sport Marketing, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-88011-877-4.

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. The Match-Up Hypothesis: Physical Attractiveness, Expertise, and the Role of Fit on Brand Attitude, Purchase Intent and Brand Beliefs. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 1–13.

- Rein, I.J.; Kotler, P.; Shields, B. The Elusive Fan: Reinventing Sports in a Crowded Marketplace; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-07-145409-4.

- Rodrigues, C.; Brandão, A.; Rodrigues, P. I Can’t Stop Hating You: An Anti-Brand-Community Perspective on Apple Brand Hate. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 1115–1133.

- Tingchi Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Minghua, J. Relations among Attractiveness of Endorsers, Match-up, and Purchase Intention in Sport Marketing in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 358–365.

- Carrillat, F.A.; O’Rourke, A.-M.; Plourde, C. Celebrity Endorsement in the World of Luxury Fashion—When Controversy Can Be Beneficial. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 1193–1213.

- Akturan, U. Celebrity Advertising in the Case of Negative Associations: Discourse Analysis of Weblogs. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 1280–1295.

- Ward, V. The Beautiful and the Damned. Available online: https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2005/12/kate-moss-cocaine-scandal (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Zahaf, M.; Anderson, J. Causality Effects between Celebrity Endorsement and the Intentions to Buy. Innov. Mark. 2008, 4, 57–65.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!