Diabetic Nephropathy (DN) is a debilitating consequence of both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes affecting the kidney and renal tubules leading to End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). As diabetes is a world epidemic and almost half of the diabetic patients develop DN in their lifetime, a large group of people is affected. Due to the complex nature of the disease, current diagnosis and treatment are not adequate to halt disease progression or provide an effective cure.

- diabetes

- nephropathy

- inflammation

- genes

- biomarker

- precision therapy

1. Introduction

Diabetes Nephropathy (DN) is a chronic kidney disease in which increasing abnormalities are developed when filtering waste and extra water from the body due to long-term hyperglycemia and hypertension. Deterioration of kidney function occurs both in Type 1 (juvenile) and Type 2 diabetes when high blood sugar levels damage micro blood vessels in the kidney. Kidney disease occurs in one of four diabetic patients [1]. In 2015, the International Diabetic Federation estimated that the prevalence of diabetes was 8.8% from ages 20 to 79 years, affecting a population of approximately 440 million people [2]. This is predicted to grow to over 550 million people by the year 2035 [3]. As diabetes is a world epidemic, a vast number of people are considered to be affected by DN.

Until recently, the extent of DN was measured by the presence of albumin in the urine of diabetic patients ( >−300 mg/mL) and defined as albuminuria or proteinuria. However, recent studies show that sufficient glomerular damage happens before the increase in albumin in the urine. Thus, new biomarkers are needed to assess the early stages of DN, as well as to measure the extent of kidney damage [4]. A proteomic study confirmed Nonalbumin Proteinuria (NAP) with the presence of alpha 1 microglobulin, globulin, nephrin and so on, as the sensitive indicators of early tubular damages [5]. When precipitation of the morning urine was analyzed with subsequent resolution by 2D gel electrophoresis, it identified a protein, kininogen-1, involved in the kalicranin–kinin system as a potential indicator, but it has not been validated in a large cohort [6].

Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) is the leading cause of End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) and is associated with increased mortality due to cardiovascular abnormalities secondary to diabetes. Although the difference between DKD and DN is difficult to distinguish clinically, DKD is used for a wide spectrum of changes in pathologies in the kidney, whereas DN is defined with distinct histological gradation. In 47 renal tissues of DKD patients, 46 types of inflammatory cells, adhesion molecules, and distinct cytokines are detected in nephropathy. The current understanding of DKD recognizes the involvement of metabolic abnormalities, hemodynamic changes, Renin–Angiotensin System (RAS) activation, and oxidative stress. While many of these approaches have been clinically implemented to slow the acceleration of DKD, current management is insufficient, both for preventing or for halting disease progression. There is a growing appreciation for the role of inflammation in modulating the process of DKD [7]. In nephropathy, the infiltration of inflammatory cells with the expression of adhesion molecules and cytokines are detected in renal tissue of DKD patients. An influx of macrophages is a principal feature during the progression of kidney diseases [8] and is highly correlated with the decline in the Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR).

Thus, the initial characterization of kidney and renal tubule damage is of prime importance in DN, as is the development of continuous improvements in therapeutic aspects. Recent advances in genetic and genomic technology have opened new avenues in developing biomarkers for the early detection of kidney damage and new therapies.

2. Brief Overview of Stages of Diabetic Nephropathy

-

(a). Glomerular lesions

-

Type 1: Glomerular Basement Membrane (GBM) Thickening.

-

Types 2: Mild (IIa) or Severe (IIb) Mesangial Expansion.

-

Types 3: Nodular Sclerosis (Kimmelstiel–Wilson lesions).

-

Types 4: Advanced Diabetic Glomerulosclerosis.

-

Interstitial abnormalities

-

Types 1: Interstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Atrophy (IFTA)

-

Types 2: Interstitial inflammatio

-

(b). Vascular lesions

-

Types 1: Arteriolar hyalinosis

-

Types 2: Presence of large vessels

-

Types 3: Arteriosclerosis

-

(c). Other glomerular lesions

3. Specialized Cells in Kidney and Renal Systems

The kidney consists of microanatomically distinct cells with specific functions. These are kidney glomerulus parietal cells, kidney glomerulus podocytes, kidney proximal tubule brush border cells, Loop of Henle thin segment cells, thick ascending limb cells, kidney distal tubule cells, collecting duct principal cells, collecting duct intercalated cells, and interstitial kidney cells. Although each cell type has an important role in maintaining the renal system, glomerular podocyte structure and function are reported to be associated with many genes. Thus, considerable efforts are directed toward the development of biomarkers and therapy of DN by manipulating genes or proteins that modulate podocyte structure and function.

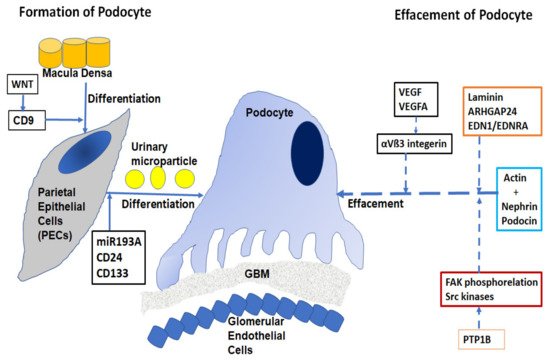

The pathogenesis of proteinuria in nephrotic diseases involves the function of the podocyte epithelial cells [10]. The filtration barrier has three layers: the glomerular epithelium, the basement membrane, and the slit diaphragm formed by the foot processes of the podocytes. The slit diaphragm is the final barrier that prevents the passage of proteins and large molecules into the urinary filtrate. Podocytes are typical epithelial cells ( Figure 1) that comprise three separate structural and functional elements: a large cell body, major extending processes, and foot processes [11].

When podocytes are injured, they undergo a process of effacement and lose their structure. Effacement is associated with proteinuria, especially in Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and diabetes. Podocyte depletion can also be correlated with the development of glomerular sclerosis and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) [12].

Approximately 40 genes have been implicated in the development of FSGS and related nephrotic diseases [13][14], including mutations in nephrin, podocin, TRPC6, actin, INF2, WT2 and, laminin/integrin receptors. Effacement of podocytes is caused by the breakdown of the actin cytoskeleton of the foot processes, allowing podocytes to be dynamic in nature with a rapidly changing ability required in filtration processes [15]. The cortical actin network binds with specialist proteins, such as nephrin and podocin of the slit diaphragm at the unique tethering points. Abnormalities of nephrin caused by mutations in the NPHS1 gene have been implicated in the autosomal recessive congenital nephrotic syndrome in a Finnish population [16]. Deletion of nonreceptor phosphatase PTP1B in podocytes conferred protection from injury and consequently, overexpression of PTP1B resulted in increased FAK phosphorylation and activity of Src kinases [17]. Laminin regulates focal adhesions, the glomerular slit diaphragm, actin-binding proteins, and actin-regulatory proteins such as small GTPases of the Rho/Rac/Cdc42 family [18]. Small GTPases are long known as important regulators of actin dynamics in podocytes. The GTPase-Activating Protein (GAP) Rho-GAP 24 (Arhgap24) was observed to be upregulated during podocyte differentiation. The crosstalk signaling between podocyte dysfunction and depletion in glomerulosclerosis is mediated by Endothelin-1 (EDN1)/Endothelin Receptor Type A (EDNRA)-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction [19]. Dysregulation of VEGF expression within the glomerulus has been reported in a wide range of nephrotic diseases [20]. The role of podocyte VEGFA in regulating αVβ3 integrin signaling in mouse GBM has been shown in vivo. αVβ3 integrin plays an important role in angiogenesis and in hypertension-induced vascular remodeling in the kidney. However, the mechanism of nephrin focal adhesion complex proteins, especially their post-translation modifications under different conditions of VEGF signaling, is unclear [21].

4. Epidemiology and Genetic Factors in DN

Familial aggregation, candidate gene approach, and Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have been widely used to identify genes that are associated with DN. Familial aggregation in DN is well observed, and familial clustering results from shared genes, environmental exposure, or their combination [22]. Several genes that predispose to diabetes have recently been identified with genetic susceptibility to the microvascular complication of nephropathy in individuals with both T1D and T2D. Polymorphisms in numerous genes are identified to play important roles in kidney diseases (reviewed by Tziastoudi et al. , 2020 [23]; Wei et al. , 2018 [24]). Some of these genes are ACE1, MTHFR, TGFB1, UMOD, PRKAG2, Apolipoprotein E, Angiotensinogen, PRKAA2, MyD88, IRAK4, TRAF6, HS6ST1 , RAB38 ACACB, PFKFB2, TNFα, IL6, IL10, IFN Gamma (IFNG), CCR5, IL8, CCL2, MCP-1, RREB1, NPHS1, NOS3, CD2AP, TRPC1, SOD1, IL1RN, GFPT2, PRKCB1, ELMO1, VEGFA, VDR, MIF1, IL1B, TNFRSF19, MMP3, MMP12, IL12RB1, EPO, GHRL, PRKCE, IL100 , IL1A, ADIPOQ, IGF1, BCL2, and GCKR.

5. Biomarkers Being Currently Developed

A wide range of biomarkers is simultaneously being developed considered to be the most useful biomarkers for DN [25]. The various approaches are 1) using biochemical pathways, 2) Mass spectrometric methods, 3) Proteomic approach, 4) miRNAs, 5) LncRNAs and 6) Autophagy. Several biomarkers are being developed, such as urinary angiotensinogen and ACE2 [26], plasma copeptin [27], plasma endostatin, serum amyloid [28], urinary NGAL, cystatin C, serum TNFR1, and TNFR2 [29]. The in vivo involvement of miR-192 in the pathogenesis of DN was demonstrated by both miR-192 gene knockout mice and mice treated with miR-192 inhibitor [30][31]. Increased miR-21 expression is documented in renal transplant patients with fibrotic kidney disease and in the urine of fibrotic patients with IgA nephropathy [32]. These miRNAs ar\e most promising agents for assessing to use as biomarkers for DN.LncRNA LINC01619 has been shown to regulate miR-27a/FoxO1 and ER stress-mediated podocyte injury in DKD [33], thus potentially could be developed as a biomarker for DN.

6. Developing Therapy Based on Inflammatory Genes

The inflammatory genes that are associated with DN could be manipulated to develop therapy fpr DN. These are TGFB1, BCL2, IGF1, ADIPOQ, IL1A, IL1RN, IL8, IL1B, MIF1, VDR, IL10, IL6, IL18, MCP-1/CCL2, VEGFA, ELMO1, IFNG, TNFα, MMP3, MMP9, MMP12, EPO, GHRL, TRAF6, and IRAK4.

Clinical studies suggested that inhibition of TGF-β/Smad and CTGF pathways could be potential targets in the treatment of glomerular diseases. TGF-β promoter blocker, pirfenidone decreased FR loss by 25% [34]. Inhibition of CTGF, using a human monoclonal antibody, FG-3019, in patients with DKD decreased albuminuria [35].

AdipoRon, an orally active synthetic adiponectin receptor agonist, ameliorated insulin resistance and reversed diabetes in db/db mice with DN specific renal features [36]. Neuroprotective agents, dexamethasone, and neurotrophins in agreement with the neural crest origin of REP cells restore Erythropoietin production and alleviate renal fibrosis[37].

Anthocyanins (Grape Seed Procyanidin (GSPE)) activates the expression of Bcl2 in diabetic mouse kidneys to suppress renal cell apoptosis. It was demonstrated that anthocyanins may exhibit protective effects against HG-induced renal injury in DN [38].

Vitamin D alone can directly suppress the HG induction of TGF-β and MCP-1 in mesangial cells by blocking Ang II accumulation [39]. Treatment of diabetic db/db mice with the MIF1 inhibitor, ISO-1, significantly decreased blood glucose levels and albuminuria and promoted wound healing in kidney tissues, suggesting that MIF1 inhibition may be a potential therapeutic strategy in DN [40].

Inhibition of MCP-1 expression with various agents, such as methanolic extract from unripe kiwi fruit (Actinidia deliciosa), dehydroabietic acid, capsaicin, curcumin modulates NFKB1, TNFα, nitric oxide, IL8, and adiponectin resulted in a reduction of DN pathogenesis with a subsequent reduction in tissue damage [41]. Lu et al., 2017 [42] suggest that curcumin is a promising treatment for DN. Its renoprotective effects occur by the inhibition of IL1B expression, NLRP3 inflammasome activity, and cleavage of caspase 1. MCC950 (also CP-456,773), was reported as a potent specific inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome [43]. These results strongly indicate that the NLRP3 inflammasome is a potential therapeutic target in DN.

Khan et al., 2005 [44] demonstrated that neutralization of endogenous TNFα reduced glomerular inflammation, crescent formation, and tubulointerstitial scarring with the preservation of renal function. TNFα blockade was effective even when introduced at the time of maximum glomerular inflammation. Bai et al., 2017 [45] demonstrated that Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) treatment proved to be effective in DN models by protecting renal function and preventing fibrosis through Lipoxin A4 (LXA4).

Combined inhibition of CCR2 and CCR5 receptors may decrease albuminuria and prevent kidney function decline in patients with DN. CCR2 blockade with an orally available small-molecule antagonist, RO5234444, alleviates proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis, and kidney failure in diabetic db/db mice [46]Gale et al., 2018 [47] indicated a modest effect of PF-04634817 in reducing albuminuria in T2D patients who received SOC treatment. Masola et al., 2012 [48] showed that sulodexide was an effective heparanase-1 inhibitor that increased MMP9-mediated switching of the autocrine loop of FGF-2.

7. Conclusion

DN is a devastating disease with progressive consequences, and about half of diabetes patients exhibit ESRD in their lifetime. Inflammatory and cytokine molecules regulate prominent genes whose products are needed to develop lesions and facilitate the progression of kidney abnormalities. For developing genomic medicine, inflammatory genes may be targeted by manipulating their mutations or even by reverting to wild type with genome corrections.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22189985

References

- Afkarian, M.; Zelnick, L.R.; Hall, Y.N.; Heagerty, P.J.; Tuttle, K.; Weiss, N.S.; De Boer, I.H. Clinical Manifestations of Kidney Disease Among US Adults With Diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA 2016, 316, 602–610.

- Federation, I.D. International Diabetes Federation IDF Diabetes Atlas; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Andersen, A.R.; Christiansen, J.S.; Andersen, J.K.; Kreiner, S.; Deckert, T. Diabetic nephropathy in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes: An epidemiological study. Diabetologia 1983, 25, 496–501.

- Sulaiman, M.K. Diabetic nephropathy: Recent advances in pathophysiology and challenges in dietary management. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 1–5.

- Ballantyne, F.C.; Gibbons, J.; O’Reilly, D.S. Urine Albumin Should Replace Total Protein for the Assessment of Glomerular Proteinuria. Ann. Clin. Biochem. Int. J. Lab. Med. 1993, 30, 101–103.

- Vitova, L.; Tuma, Z.; Moravec, J.; Kvapil, M.; Matejovic, M.; Mares, J. Early urinary biomarkers of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus show involvement of kallikrein-kinin system. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 112.

- Matoba, K.; Takeda, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Kawanami, D.; Utsunomiya, K.; Nishimura, R. Unraveling the Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3393.

- Tian, S.; Chen, S.Y. Macrophage polarization in kidney diseases. Macrophage Houst 2015, 2, e679.

- Tervaert, T.W.C.; Mooyaart, A.; Amann, K.; Cohen, A.H.; Cook, H.T.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Ferrario, F.; Fogo, A.B.; Haas, M.; De Heer, E.; et al. Pathologic Classification of Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 556–563.

- Shankland, S.J. The podocyte’s response to injury: Role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 2131–2147.

- Quaggin, S.E.; Kreidberg, J.A. Development of the renal glomerulus: Good neighbors and good fences. Development 2008, 135, 609–620.

- Wiggins, R.-C. The spectrum of podocytopathies: A unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 1205–1214.

- Hall, G.; Gbadegesin, R.A. Translating genetic findings in hereditary nephrotic syndrome: The missing loops. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2015, 309, F24–F28.

- Garg, P. A Review of Podocyte Biology. Am. J. Nephrol. 2018, 47, 3–13.

- Ronco, P. Proteinuria: Is it all in the foot? J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2079–2082.

- Kestilä, M.; Lenkkeri, U.; Männikkö, M.; Lamerdin, J.; McCready, P.; Putaala, H.; Ruotsalainen, V.; Morita, T.; Nissinen, M.; Herva, R.; et al. Positionally Cloned Gene for a Novel Glomerular Protein—Nephrin—Is Mutated in Congenital Nephrotic Syndrome. Mol. Cell 1998, 1, 575–582.

- Ma, H.; Togawa, A.; Soda, K.; Zhang, J.; Lee, S.; Ma, M.; Yu, Z.; Ardito, T.; Czyzyk, J.; Diggs, L.; et al. Inhibition of Podocyte FAK Protects against Proteinuria and Foot Process Effacement. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1145–1156.

- Lovric, S.; Ashraf, S.; Tan, W.; Hildebrandt, F. Genetic testing in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: When and how? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 1802–1813.

- Daehn, I.; Casalena, G.; Zhang, T.; Shi, S.; Fenninger, F.; Barasch, N.; Yu, L.; D’Agati, V.; Schlondorff, D.; Kriz, W.; et al. Endothelial mitochondrial oxidative stress determines podocyte depletion in segmental glomerulosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1608–1621.

- Eremina, V.; Sood, M.; Haigh, J.; Nagy, A.; Lajoie, G.; Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.-P.; Kikkawa, Y.; Miner, J.H.; Quaggin, S.E. Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 707–716.

- Garg, P.; Rabelink, T. Glomerular proteinuria: A complex interplay between unique players. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011, 18, 233–242.

- Freedman, B.I.; Bostrom, M.; Daeihagh, P.; Bowden, D.W. Genetic Factors in Diabetic Nephropathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 1306–1316.

- Tziastoudi, M.; Stefanidis, I.; Zintzaras, E. The genetic map of diabetic nephropathy: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 13, 768–781.

- Wei, L.; Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Xiong, X.; Han, Y.; Zhu, X.; Sun, L. The Susceptibility Genes in Diabetic Nephropathy. Kidney Dis. 2018, 4, 226–237.

- Colhoun, H.M.; Marcovecchio, M.L. Biomarkers of diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 996–1011.

- Burns, K.D.; Lytvyn, Y.; Mahmud, F.; Daneman, D.; Deda, L.; Dunger, P.D.; Deanfield, J.; Dalton, R.N.; Elia, Y.; Har, R.; et al. The relationship between urinary renin-angiotensin system markers, renal function, and blood pressure in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2017, 312, F335–F342.

- Velho, G.; El Boustany, R.; Lefèvre, G.; Mohammedi, K.; Fumeron, F.; Potier, L.; Bankir, L.; Bouby, N.; Hadjadj, S.; Marre, M.; et al. Plasma Copeptin, Kidney Outcomes, Ischemic Heart Disease, and All-Cause Mortality in People With Long-standing Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2288–2295.

- Dieter, B.P.; McPherson, S.M.; Afkarian, M.; De Boer, I.H.; Mehrotra, R.; Short, R.; Barbosa-Leiker, C.; Alicic, R.Z.; Meek, R.L.; Tuttle, K. Serum amyloid a and risk of death and end-stage renal disease in diabetic kidney disease. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2016, 30, 1467–1472.

- Garg, V.; Kumar, M.; Mahapatra, H.S.; Chitkara, A.; Gadpayle, A.K.; Sekhar, V. Novel urinary biomarkers in pre-diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2015, 19, 895–900.

- Bhatt, K.; Kato, M.; Natarajan, R. Mini-review: Emerging roles of microRNAs in the pathophysiology of renal diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2016, 310, F109–F118.

- Kato, M.; Arce, L.; Wang, M.; Putta, S.; Lanting, L.; Natarajan, R. A microRNA circuit mediates transforming growth factor-β1 autoregulation in renal glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 358–368.

- Lin, L.; Gan, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, W.; Sun, Y.; Tang, X.; Kong, D.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. MicroRNA-21 inhibits SMAD7 expression through a target sequence in the 3′ untranslated region and inhibits proliferation of renal tubular epithelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 707–712.

- Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Gong, R. Long noncoding RNA: An emerging player in diabetes and diabetic kidney disease. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 1321–1339.

- Cho, M.E.; Smith, D.C.; Branton, M.H.; Penzak, S.R.; Kopp, J. Pirfenidone Slows Renal Function Decline in Patients with Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 906–913.

- Adler, S.G.; Schwartz, S.; Williams, M.E.; Arauz-Pacheco, C.; Bolton, W.K.; Lee, T.; Li, N.; Neff, T.B.; Urquilla, P.R.; Sewell, K.L. Phase 1 Study of Anti-CTGF Monoclonal Antibody in Patients with Diabetes and Microalbuminuria. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1420–1428.

- Okada-Iwabu, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Iwabu, M.; Honma, T.; Hamagami, K.I.; Matsuda, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tanabe, H.; Kimura-Someya, T.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 2013, 503, 493–499.

- Asada, N.; Takase, M.; Nakamura, J.; Oguchi, A.; Asada, M.; Suzuki, N.; Yamamura, K.-I.; Nagoshi, N.; Shibata, S.; Rao, T.N.; et al. Dysfunction of fibroblasts of extrarenal origin underlies renal fibrosis and renal anemia in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3981–3990.

- Wei, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Chen, S.; Hou, B.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Duan, H. Anthocyanins inhibit high glucose-induced renal tubular cell apoptosis caused by oxidative stress in db/db mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 1608–1618.

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, W.; Sun, L.; Szeto, F.L.; Wong, K.E.; Li, X.; Kong, J.; Li, Y.C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 targeting of NF-kappaB suppresses high glucose-induced MCP-1 expression in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2007, 72, 193–201.

- Lan, H.Y.; Yang, N.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Xue, Q.Y.; Mu, W.; Isbel, N.M.; Metz, C.N.; Bucala, R.; Atkins, R.C. Expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in human glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 499–509.

- Panee, J. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 (MCP-1) in obesity and diabetes. Cytokine 2012, 60, 1–12.

- Lu, M.; Yin, N.; Liu, W.; Cui, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, E. Curcumin Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy by Suppressing NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling. BioMed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1516985.

- Coll, R.C.; Hill, J.R.; Day, C.J.; Zamoshnikova, A.; Boucher, D.; Massey, N.L.; Chitty, J.L.; Fraser, J.A.; Jennings, M.P.; Robertson, A.A.V.; et al. MCC950 directly targets the NLRP3 ATP-hydrolysis motif for inflammasome inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 556–559.

- Khan, S.B.; Cook, H.T.; Bhangal, G.; Smith, J.; Tam, F.W.; Pusey, C.D. Antibody blockade of TNF-α reduces inflammation and scarring in experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 1812–1820.

- Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, L.; Jiang, H. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reverse Diabetic Nephropathy Disease via Lipoxin A4 by Targeting Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β)/smad Pathway and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 3069–3076.

- Sayyed, S.G.; Ryu, M.; Kulkarni, O.P.; Schmid, H.; Lichtnekert, J.; Grüner, S.; Green, L.; Mattei, P.; Hartmann, G.; Anders, H.-J. An orally active chemokine receptor CCR2 antagonist prevents glomerulosclerosis and renal failure in type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 68–78.

- Gale, J.D.; Gilbert, S.; Blumenthal, S.; Elliott, T.; Pergola, P.E.; Goteti, K.; Scheele, W.; Perros-Huguet, C. Effect of PF-04634817, an Oral CCR2/5 Chemokine Receptor Antagonist, on Albuminuria in Adults with Overt Diabetic Nephropathy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2018, 3, 1316–1327.

- Masola, V.; Onisto, M.; Zaza, G.; Lupo, A.; Gambaro, G. A new mechanism of action of sulodexide in diabetic nephropathy: Inhibits heparanase-1 and prevents FGF-2-induced renal epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 213.