Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, increasing with age and comorbidities. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a chronic sleep disorder more common in older men. It has been shown that OSA is linked to AF. Nonetheless, the prevalence of OSA in patients with AF remains unknown because OSA is significantly underdiagnosed.

- atrial fibrillation

- arrhythmia

- obstructive sleep apnea

1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, with high mortality and morbidity [1,2,3]. Its incidence and the social and economic burden of AF on healthcare systems worldwide are rising significantly [1,2,4,5,6,7]. Unfortunately, despite extensive research, the mechanisms underlying AF are complex and not completely understood yet [1,2,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common chronic disorder affecting about 2–4% of the adult population, being more common in old men [19]. The condition is characterized by repetitive episodes of the complete or partial collapse of the upper airway during sleep, with a consequent cessation/reduction of the airflow [20]. Sleep apnea has been implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including arrhythmias, hypertension, heart failure (HF), and stroke [21,22]. A link between AF and OSA [23,24,25,26] has been described, and it has been assessed that these two pathological conditions share many common unmodifiable and modifiable risk factors, including sex, age, obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking, Helicobacter pylori infection, etc. [3,14,27,28,29].

Nonetheless, the prevalence of OSA in patients with AF is unknown because OSA is generally underdiagnosed [19,20]. Furthermore, controversy over this association and its directionality exists, because of the high incidence of cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities in patients with OSA and AF. Patients with OSA have a higher incidence of AF than the general population [23,25,30].

2. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Atrial Fibrillation

2.1. Relation between OSA and AF

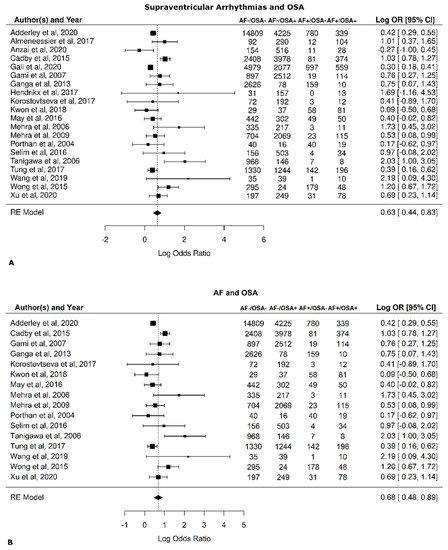

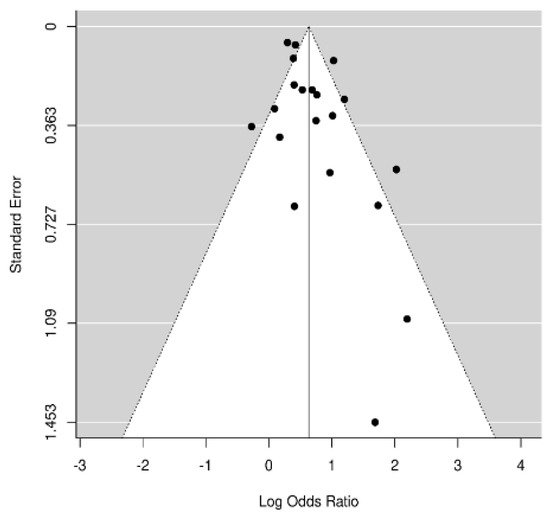

The composite log odds ratio for all the studies was 0.63 (p < 0.001), indicating a strong positive link between the two diseases. More specifically, the balance between AF+ and AF− in patients with OSA is 1.88 greater than this ratio in patients without OSA. In other words, the incidence of AF is 88% higher in patients with OSA. The log of the odds ratios (Log OR) for supraventricular arrhythmias and OSA (Figure 1A) and AF and OSA (Figure 1B) are shown in Figure 1 (funnel diagram in Figure 2). There was no significant difference between those papers that refer to supraventricular arrhythmias and those that refer to AF (0.63 [0.44, 0.83] vs. 0.68 [0.48, 0.89], respectively).

Figure 1. Risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Forest plots. (A) All references, including those that did not discriminate between arrhythmia in general and AF, were examined [30,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. (B) Only references that include only AF were examined [39,41,43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Figure 2. Risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Funnel plot.

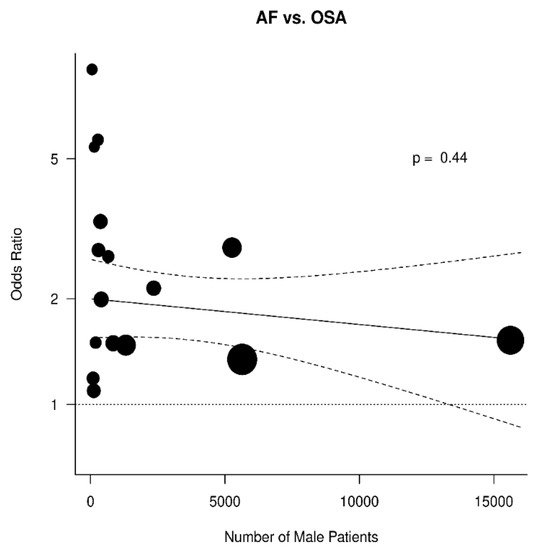

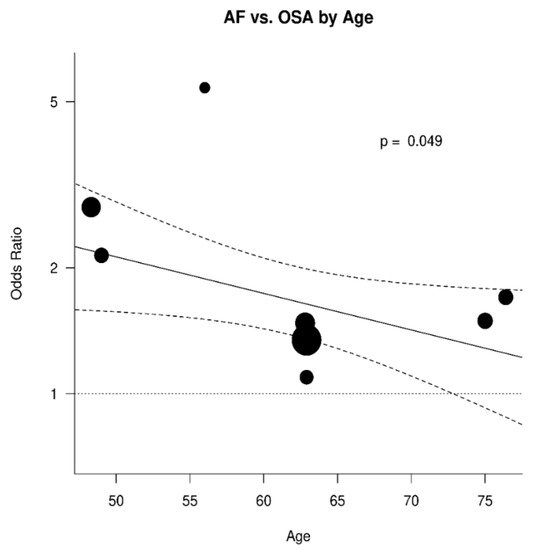

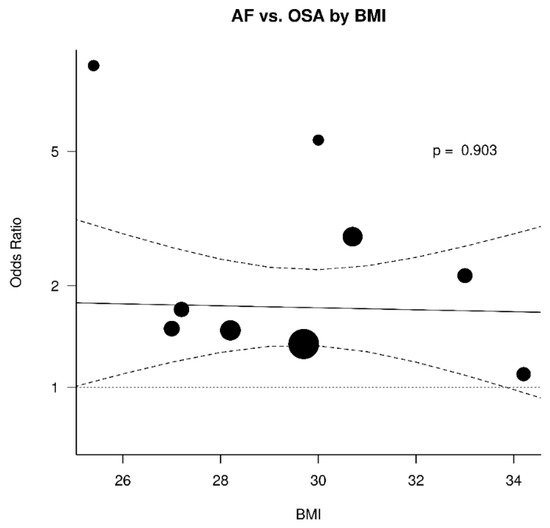

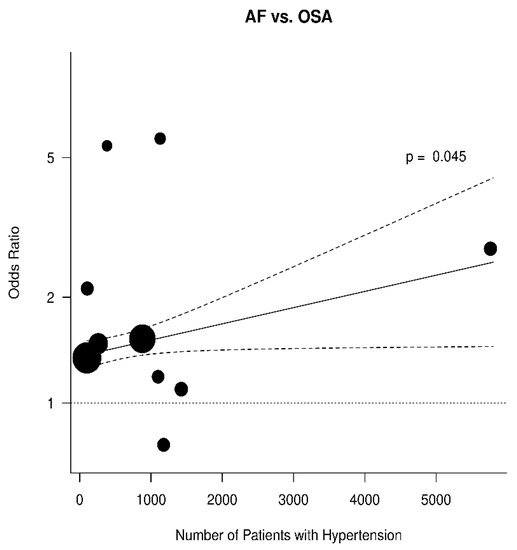

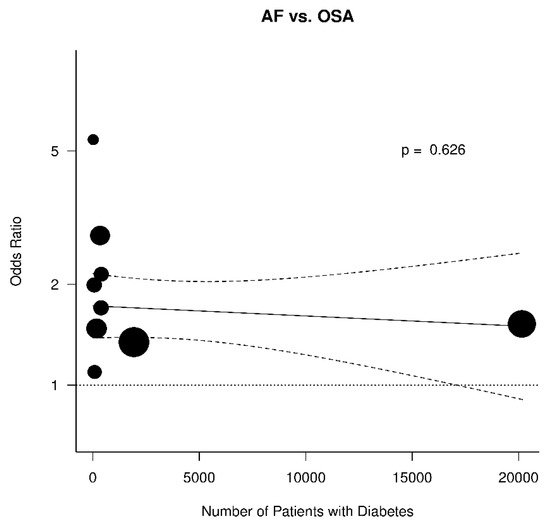

The results were further analyzed for the possible effects of sex, age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and BMI. The respective diagrams are shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. Age (p = 0.04) and hypertension (p = 0.04) were found to affect the incidence of OSA in AF patients. An increase of 5 years corresponded to a reduction by 9.4% in incidence of AF. In contrast, no effect was found for sex (0.44), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.62), and BMI (p = 0.9).

Figure 3. Effect of sex in the odds ratio for atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Figure 4. Effect of age in the odds ratio for atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Figure 5. Effect of body mass index (BMI) in the odds ratio for atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Figure 6. Effect of hypertension in the odds ratio for atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Figure 7. Effect of diabetes mellitus in the odds ratio for atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

2.4. Discussion

A significant association between OSA and AF has been advocated [58] as well as a significant “interplay” between these two pathological entities [58]. A recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) has confirmed this association [59].

In contrast, the prevalence of central sleep apnea (CSA) in patients with AF is less clarified, although it is high in patients with HF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [60].

However, OSA and AF share many common risk factors [61]. Therefore, the association of OSA and AF might be due to shared CVD and obesity. Hence, a direct link between the two diseases is still debated since the close association between CVD and both these pathologies, might obscure a directly causal relationship between OSA and AF. We performed a review of the published paper, involving 54,271 patients assessing the incidence of AF in OSA patients. We found a strong association between OSA and AF. Indeed, we found that the incidence of AF is 88% higher in patients with OSA.

This confirms the results from Chao et al. including 579,521 patients, of which 4082 had OSA. After a 9.2-year average follow-up, the incidence of AF was 0.7% in patients without OSA and 1.38% in patients with OSA (p < 0.001) [62]. Nonetheless, OSA and AF share many common risk factors therefore, the presence of one may promote the development of the other. Hence it is not clear whether this association is primary or mediated by shared risk factors. For this reason, we wanted to go further, carrying out a meta-regression to test whether this association was independent, or it was the results of the interaction of OSA with other shared cardiovascular risks with common pathophysiological mechanisms. The risk factors that the two diseases have include: Obesity or high body max index (BMI), older age, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, dyslipidemia, and male gender [61,63,64,65].

Of the abovementioned factors, age and hypertension were found in this meta-analysis to significantly contribute to the correlation between AF and OSA. These factors are independently related to both AF and OSA. Additionally, these risk factors are also closely interrelated. Hypertension results from multiple genetic and environmental factors, however, it is closely related to the aging process and the resulting increasing arterial stiffness [66].

Increased age was found to be correlated with 9.4% reduced incidence of AF in patients with OSA (p < 0.05). Although children and adolescents can also have OSA, the prevalence of the disease is significantly higher in adults and increases with age [67]. The prevalence of AF is also associated with aging. Therefore, the mechanisms involved into such a reduction in AF incidence are not entirely known.

The second factor that was found to be correlated with increased incidence of AF in patients with OSA was hypertension that contributes to the development of anatomical abnormalities that lead to the development of AF [68].

A recent meta-analysis showed that daytime, nighttime, and 24-h systolic blood pressure (BP) are similarly associated with future AF and that ambulatory systolic BP is a better predictor than clinic BP [69]. The mechanism involved in the effect of hypertension on AF is not well known but two main mechanisms are proposed. First, hypertension can cause hemodynamic changes and an increase of pressure in the left atrium leading to enlargement of the atrium, and second, hypertension-related activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and autonomic dysregulation can also induce fibrosis in the left atrium (LA) contributing to the development of AF [70].

Hypertension and OSA have several common factors in pathophysiology, including gender, obesity, lifestyle, impaired quality of sleep, RAAS, and increased fluid distribution [63]. OSA is a cause of secondary hypertension as apneas during the night can result in surges in blood pressure and subsequently elevated average systolic and diastolic pressure.

The other factors that were examined, namely BMI, diabetes, smoking, dyslipidemia, and sex were not found to influence the correlation between OSA and AF even though they are known to be predictors for both OSA and AF.

Although these connections are still speculative, there are possible pathophysiological links between AF and OSA. Having OSA may lead to initiation or exaggeration of the effects of AF through a series of mechanisms [71]. OSA patients, can develop negative intrathoracic pressure [72]. This negative pressure may lead to an increase of afterload as well as atrial stretch [61]. As a result, there can be left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and electrical remodeling leading to increased chances of AF [61]. OSA may also lead to smaller refractory and action potential periods that arise from the increased vagal and sympathetic activity leading to structural and electrical remodeling in the atria that contribute to the onset of AF [73]. Furthermore, a rise in CO2 and reduction of O2, leads to an increase in inflammation and oxidative stress that may also contribute to the development of AF [74]. So, OSA may lead to initiation or worsening of AF via the distortion of the normal electrophysiological mechanisms of the heart [26,58,75,76]. Under this perspective it can be hypothesized that treatment of OSA may contribute to reducing the AF symptoms and this hypothesis is supported by research data. In a recent meta-analysis, it was interestingly shown that CPAP treatment of OSA is associated with a reduction of AF recurrence in patients who were not treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or electrical cardioversion(ECV) [77]. In addition, non-selective B blockers (BB) may reduce heart rate (HR) during OSA and avoid bradycardias.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11051242

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!