The Teotihuacan quadruple flutes are among the most elaborate ceramic fipple flute instruments documented for Mesoamerica.

- Teotihuacan

- musical instruments

- sonic artefacts

- aerophones

1. Quadruple Flute Organology

2. The Three Best-Preserved Teotihuacan Quadruple Flutes

3. Previous Reconstruction Attempts and Current Playing Condition of the Finds

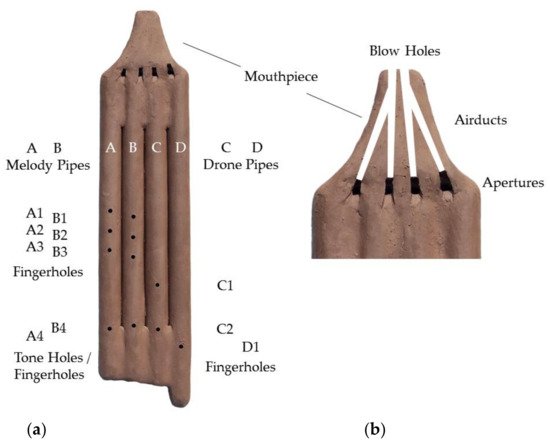

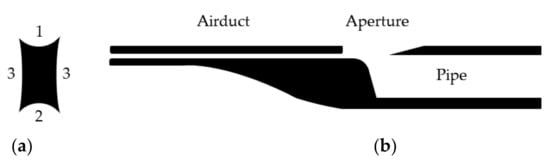

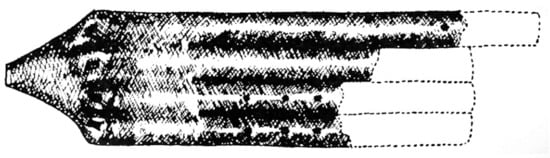

As mentioned before, the Zacuala quadruple was subject to at least three restoration/reconstruction attempts, which are not fully correct according to current research. Notably, the reconstructions resulted in differing total lengths of the sonic artefact, ranging between 63.5 cm in the first 3 and, after a prolongation of the length of pipe D, 74.5 cm in the last reconstruction. On the other hand, the width of 13.2 cm and the height of 3.8 cm were always maintained and correspond to the original size (the height equivalent to the maximum outer diameter of the pipes). From the preserved part of the original find only a sketch has been published (Figure 5). The sketch does not include several parts of the distal end of some of the pipes, one fragment still presenting a fingerhole/tone hole inserted erroneously on the inferior side of the instrument (in pipe A in the first reconstruction and in pipe C in the second reconstruction). In the first reconstruction, pipes A–C have been given the same length, with the length of pipe D only a few millimetres larger. For the second reconstruction, the length of pipe D has been enlarged, and for the last attempt even more. During the second reconstruction attempt also the diameter of some of the fingerholes, originally presenting between 4.5–5.5 mm, has been substantially modified, resulting in diameters between 2.9–5.5 mm. According to the pre-Columbian flute design, usually presenting only small deviations of the fingerhole diameters of not more than 0.5–1.0 mm in one and the same instrument, the present condition must be challenged. In addition, due to the lack of knowledge on comparative material, the fingerholes and tone holes of the unpreserved parts in pipe A (A4), B (B4), and C (C1; C2) were never included. The fingerhole/tone hole currently situated on the inferior side of pipe C, most probably corresponds to A4, and the corresponding fragment to pipe A. The Anahuacalli-1 quadruple also has not been restored fully and satisfyingly, especially in terms of the length of pipe D and the omission of some of the fingerholes of pipes B (B2; B3), C (C1) and D (D1).

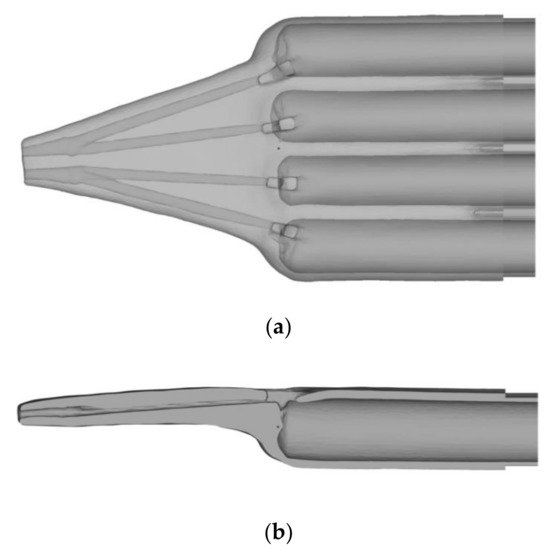

4. Manufacture and Design of Playable Reproductions with Copied and Reconstructed Parts

-

producing four tubes with flat pieces of clay wrapped around wooden bars;

-

joining the four tubes by filling an amount of clay in between the tubes in the upper and lower section of the pipes and in between the tubes on the inferior side;

-

cutting the four apertures in the tubes;

-

producing the mouthpieces in two parts (a larger lower and a smaller upper section, the latter presenting the blow holes): the inferior side of the lower section with four flat sticks in the size of the airducts, then covered by the superior side of the lower section; the same repeated with the upper section;

-

joining the lower section of the mouthpiece with the tubes by bringing the remaining sticks in line with the edges; carefully removing the sticks and testing the sound; for support adding clay at the joint of the inferior side of the mouthpiece and the four tubes;

-

joining the upper section of the mouthpiece with the lower section; removing the sticks and testing the sound; eventually adjusting the position of the mouthpiece so that all airducts are aligned well with the apertures, especially the edges;

-

bringing the form of the aperture into shape and testing the sound; eventually slightly adjusting the airduct-aperture configuration;

-

perforating the fingerholes/tone holes with a reed tube by measuring the position of the fingerhole A2 and from there on deducting all other fingerholes/tone holes; then testing the sound; eventually slightly adjusting the individual size of the fingerholes/tone holes;

-

finishing by smoothing the entire surface, eventually applying engobe and partially polishing the surface.

-

drying and firing. With the respective preparation, construction and drying processes of the individual pieces, at least three work days of 4 to 5 h each are required for production, and then at least a couple of days for the drying process, before the instrument can be fired.

Notes

1. So far documented are approximately 40 fragmented mouthpieces from the Teotihuacan Mapping Project at the Research Laboratory of the Arizona State University, San Juan Teotihuacán (RL-ASU), for a selection see [1] (p. 74–76, Figure 5); finds from Atetelco, La Ventilla and other excavation sites at the Ceramoteca of the Zona de Monumentos Arqueológicos de Teotihuacán, San Martín Teotihuacán (C-ZMAT, Inv. 10-600289; 10-599898; Elem. 19897; 57888; further finds without inventory no.), for a selection see [1] (p. 71, 74–76, Figure 2); finds from Zacuala, Yayahuala and Tetitla, see [3] (p. 236, Figure 126), [4] (p. 106, Figure 83D,E); and two finds from Teopancazco, see [2] (p. 202, 205, Figures. 4.47–4.48). For a distribution map, based on the finds stored in the RL-ASU and the C-ZMAT, see [1] (p. 83, Figure 9).

2. The miniatures are produced with a flat inferior side and the superior side simulating the instrument in relief, frequently simulating the fingerholes, apertures, and decoration, see [1] (pp. 76-81: Figures 6–8); [3] (pp. 237–238, 240, Figures 127–129); [5] (p. 379, Figure 268); [6] (p. 13, Table 4); [7] (p. 46, Photo 129); [8] (p. 3, Photo 130). A series of finds is stored in the RL-ASU and the C-ZMAT; one further find in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (MNA), the latter without inventory number.

3. Samuel Martí gave the length of 53.5 cm for the first restoration/reconstruction [13] (pp. 48–49, Figure 28), but when bringing his top view photograph to scale (and taking into account the photographic distortion of the object resulting from the position of the photographer and the angle of her or his camera) it becomes clear that a typo occurred, as an instrument of 53.5 cm in length would present a width of not more than 10.8 cm. When bringing the photograph to the scale of 63.5 cm in length and recompute the photographic distortion, the width of 13.2 cm is matched.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/heritage5010009

References

- Arndt, D.J. The Quadruple Flutes of Teotihuacan Resurfaced. In Flower World–Music Archaeology of the Americas; Stöckli, M., Howell, M., Eds.; Ekho Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 3, pp. 67–100.

- Zalaquett Rock, F.A.; Espino Ortiz, D.S.; Vázque Campa, V. Instrumentos sonoros procedentes de las excavaciones de Teopancazco. In Teopancazco Como Centro de Barrio Multiétnico de Teotihuacan: Los Sectores Funcionales y el Intercambio a Larga Distance; Manzanilla, L.R., Ed.; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; pp. 181–212.

- Séjourné, L. Arquitectura y Pintura en Teotihuacán; Siglo XXI Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 1966.

- Séjourné, L. Un Palacio en la Ciudad de los Dioses ; INAH: Mexico City, Mexico, 1959.

- Manzanilla, L. Anatomía de un Conjunto Residencial Teotihuacano en Oztayahualco, Vol 1: Las Excavaciones; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1993.

- Sugiyama, S. Censer Symbolism and the State Polity in Teotihuacán. 2002. Available online: http://www.famsi.org/reports/97050/97050Sugiyama01Text.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Sugiyama, S.; Censer Symbolism and the State Polity in Teotihuacán, III. Anthropomorphic Attributes of Deities and Characters. 2002. Available online: http://www.famsi.org/reports/97050/97050Sugiyama01Images3.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Sugiyama, S.; Censer Symbolism and the State Polity in Teotihuacán, IV. Other motifs: Different Representations and Symbols. 2002. Available online: http://www.famsi.org/reports/97050/97050Sugiyama01Images4.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Both, A.A. Sonic Artefacts of Teotihuacan, Mexico (Horns, Trumpets, and Pipes). Acoustics 2021, 3, 507–544.

- Boiles, C. La flauta triple de Tenenexpan. La Palabra Y El Hombre 1965, 34, 213–222.

- Zalaquett Rock, F.A.; Espino Ortiz, D.S. Flautas triples de Jaina y Copán: Un estudio arqueoacústico. Ancient Mesoamerica 2018, 30, 419–438.

- Branly, M.D.Q. (Ed.) Teotihuacan: Geheimsnisvolle Pyramidenstadt; Exhibition Catalogue; Somogy éditions d’art/museé du quai Branly: Paris, France, 2009.

- Martí, S. Alt-Amerika; Musikgeschichte in Bildern, Volume 2; Musik des Altertums, Lieferung 7; VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik: Leipzig, Germany, 1970.

- Castellanos, P. Horizontes de la Música Precortesiana; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1970.

- Séjourné, L. Arqueología de Teotihuacan: La cerámica; Fondo de Cutura Económico: Mexico City, Mexico; Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1966.

- Martí, S. Instrumentos Musicales Precortesianos; INA: Mexico City, Mexico, 1955.