Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Millets are termed as “yesterday’s coarse grains and today’s nutri-cereals.” Millets are considered to be “future crops” as they are resistant to most of the pests and diseases and adapt well to the harsh environment of the arid and semi-arid regions of Asia and Africa.

- millets

- Processing

1. Introduction

Millets are termed as “yesterday’s coarse grains and today’s nutri-cereals.” Millets are considered to be “future crops” as they are resistant to most of the pests and diseases and adapt well to the harsh environment of the arid and semi-arid regions of Asia and Africa [1]. Millets are small-seeded grains, the most common and important for food being sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), finger millet (Eleusine carocana), teff (Eragrostis tef), proso millet (Panicum miliaceum), kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum), foxtail millet (Setaria italica), little millet (Panicum sumatrense) and fonio (Digitaris exilis) [1]. After decades of negligence, nutri-cereals are making a strong comeback in the Indian cereal’s production segment. India dominates the global production of millets with a total share of about 40.62% and an estimated production of about 10.91 million tonnes during 2018–2019 [2]. Although India ranks first in nutri-rich millet production and second in rice and pulses across the globe, it also—unfortunately—ranks second in child malnutrition incidences. India is home to more than one-third of the world’s malnourished children [3]. By contrast, the country has also become a hub for diabetic and overweight populace, putting the country under a double burden of malnutrition [4]. The majority of millets are three to five times more nutritious than most cereals (rice, Oryza sativa; wheat, Triticum aestivum; maize, Zea mays) in terms of vitamins, fiber, proteins, and minerals (calcium and iron) and are gluten-free; hence, they are known as “superfoods” [2]. The nutri-rich millets are the viable solution to reduce the rising incidences of malnutrition and metabolic disorders and can enhance the nutrition and food security of the country.

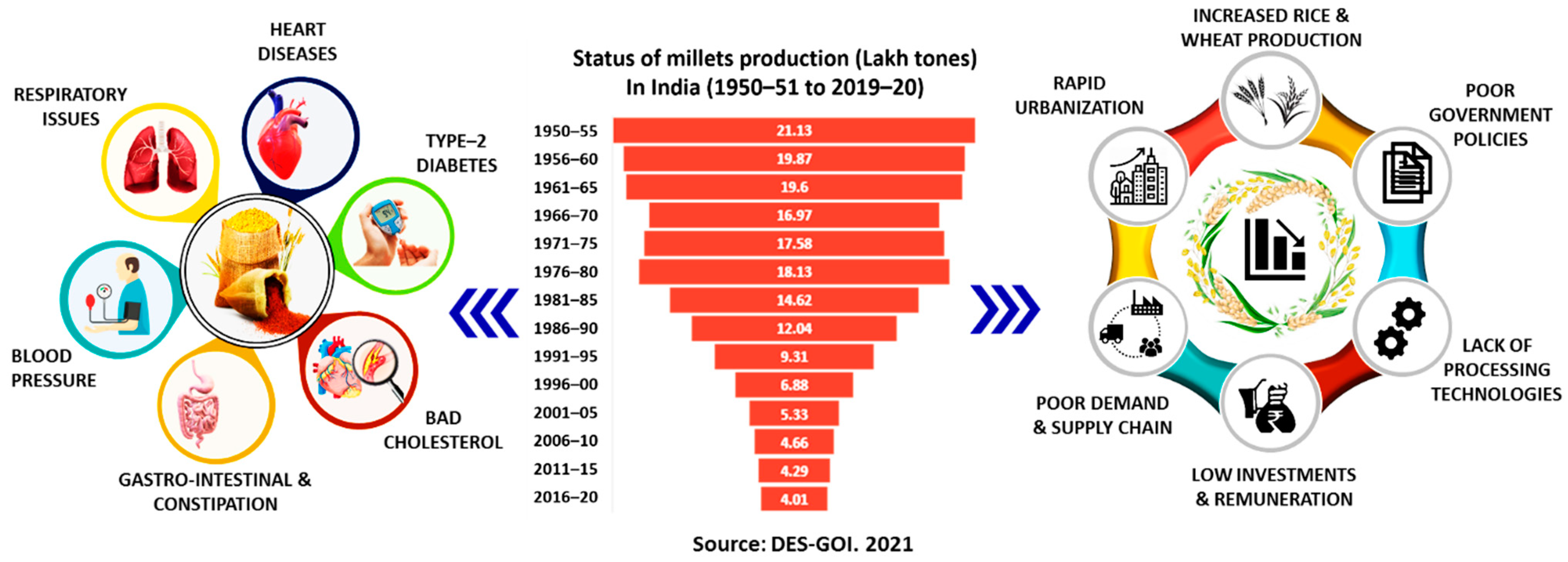

Millets are a highly nutritious crop and contain considerable amounts of vitamins and minerals. Millets are a good source of energy, dietary fiber, slowly digestible starch, and resistant starch, and thus provide sustained release of glucose and thereby satiety [5][6]. Compared to cereals, millets are a good source of protein- and sulphur-containing amino acids (methionine and cysteine) and have a better fatty acid profile [5][7]. However, millets contain a limited amount of lysine and tryptophan, which varies with the cultivar. Millets are rich in vitamin E and vitamin B and in minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, manganese, potassium, and iron [1][8]. The abundant nutrients of millets provide multiple benefits such as reducing the incidence of cancer [9][10], obesity and diabetes [11], cardiovascular diseases [12][13], gastrointestinal problems [14], migraine, and asthma [1][15]. Consumption of millets helps manage hyperglycemia due to their lente carbohydrate and high dietary fiber content, thus making millets a perfect food for the diabetic populace [3][15]. Therefore, millets play an important role in the modern diet as a potential source of essential nutrients, especially in underdeveloped and developing countries [16]. Although millets have a diversified and high food value, their consumption, especially by the Indian populace, has not reached a significant level due to various factors, depicted in Figure 1. Recently, these grains have been slowly fueling the start-up revolution to improve nutri-rich food availability and create employment.

Figure 1. Millets: health benefits, production, and challenges in India. Data taken from various issues [17].

Millets are usually processed before consumption to remove the inedible portions, extend the shelf life, and improve nutritional and sensory properties. Primary processing techniques such as dehulling, soaking, germination, roasting, drying, polishing and milling (size reduction) are followed to make millets fit for consumption. At the same time, modern or secondary processing methods such as fermenting, parboiling, cooking, puffing, popping, malting, baking, flaking, extrusion, etc., are used to develop millet-based value-added processed food products [8]. Although these processing techniques aim to enhance the digestibility and nutrient bioavailability, a significant amount of nutrients are lost during subsequent processing [18]. This review article aims to provide an overview of the effect of processing techniques on the nutritional properties of important Indian millets, viz. pearl millet, proso millet, kodo millet, foxtail millet, and little millet.

2. Nutritional Profile of Millets

The nutritional content of food is an important factor in the maintenance of a human body’s metabolism and wellness. The nutritional content is critical for developing and maximizing the human genetic potential. Millet’s nutrition is comparable to major staple cereals (rice, wheat, and maize), since they are an abundant source of carbohydrates, protein, dietary fiber, micronutrients, vitamins and phytochemicals. Millets provide energy ranging from 320–370 kcal per 100 g of consumption (Table 1). Millets have a larger proportion of non-starchy polysaccharides and dietary fiber compared to staple cereals and comprise 65–75% carbohydrates. Millets with high dietary fiber provide multiple health benefits such as improving gastrointestinal health, blood lipid profile, and blood glucose clearance. Millets with minimal gluten and low glycemic index are healthy options for celiac disorder and diabetes [19]. Millets are also rich in health-promoting phytochemicals such as phytosterols, polyphenols, phytocyanins, lignins, and phyto-oestrogens. These phytochemicals act as antioxidants, immunological modulators, and detoxifying agents, preventing age-related degenerative illnesses such as cardiovascular diseases, type-2 diabetes, and cancer [1]. A study [20] reported that millets contain about 50 different phenolic groups and their derivatives with potent antioxidant capacity, such as flavones, flavanols, flavononols, and ferulic acid. A significant amount of phenolic components, which are important antioxidants in millets, are found in bounded form in proso and finger millet and in free form in pearl millet [21]. Another study [22] reported that proso millet comprises various phytochemicals such as syringic acid, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, and p-coumaric. It has also been reported that almost 65% of the phenolics are present in the bound fraction. The presence of these phytochemicals and important antioxidants indicates the potential benefits of millets to human health. A detailed summary of the nutritional profile of selected Indian millets is discussed below and highlighted in Table 1.

-

Proso millet has a higher nutritional value when compared with staple cereals as it contains a higher concentration of minerals and dietary fiber (Table 1). Proso millet is a rich source of vitamins and minerals such as iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), potassium (K), phosphorus (P), zinc (Zn), magnesium (Mg), vitamin B-complex, niacin, and folic acid. Proso millet contains essential amino acids in significantly higher quantities, except for lysine, the limiting amino acid. However, proso millet has an almost 51% higher essential amino acid index than wheat [23]. Moreover, the products prepared from proso millet exhibit a lower glycemic response than staple cereal-based products. A review reported that products prepared from proso millet show a significantly lower glycemic index (GI) compared to wheat- and maize-based products [24].

-

Pearl millet shows an energy value comparable to the staple cereals. Pearl millet contains a lesser amount of carbohydrates than the staple cereals, and it mainly contains high amylose starch (20–22%), and the insoluble dietary fiber fraction helps in exhibiting a lower glycemic response. Pearl millet protein is gluten-free and contains a higher prolamin fraction, making it suitable for people with gluten sensitivity. The amino acid score in pearl millet is good; however, it is poor source of lysine, threonine, tryptophan, and other sulphur-containing amino acids [22][25]. Pearl millet is high in omega-3 fatty acids and also important nutritional fatty acids such as alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid. It also contains other micronutrients such as Fe, Zn, copper (Cu), K, Mg, P, manganese (Mn), and B-vitamins [22].

-

Kodo millet provides an energy value similar to the other millets and staple cereals. However, with the exception of finger millet, the protein content of kodo millet is lower than that of other selected millets and it provides gluten-free protein (Table 1). Kodo millets contains high amounts of vitamins and minerals, especially B-complex vitamins, B6, niacin and folic acid, Fe, Ca, Mg, K, and Zn. Kodo millet is very easy to digest and thus can be beneficial for infant and geriatric product formulation.

-

Foxtail millet has a greater nutritional value compared to major cereals such as wheat and rice due to its copious dietary fiber content, resistant starch, vitamins, minerals, and essential amino acids, except for lysine and methionine, but it is richer than most cereals. Among the selected millets, foxtail millet contains the highest protein (Table 1). Foxtail millet also contains a high amount of stearic and linoleic acids, which helps in maintaining a good lipid profile.

-

Finger millet has the highest carbohydrate content among the selected millets. However, carbohydrates consist primarily of slowly digestible starch, dietary fiber, and resistant starch and thus offer a low glycemic index compared to most common cereals such as rice and wheat [26]. Finger millet contains around 7% protein (Table 1), which is less than that of other millets, but it has a good amino acid score and contains more threonine, lysine, and valine than other millets. Subsequently, micronutrients such as Ca, Fe, Mg, K, and Zn, as well as B-vitamins, especially niacin, B6, and folic acid, are abundantly available.

-

The nutritional value of little millet is comparable to other cereal and millet crops. It contains around 8.7% protein and balanced amino acids, and it is a rich source of sulphur-containing amino acids (cysteine and methionine) and lysine, which is lacking in most cereals [27]. It is generally considered to induce a lower glycemic response due to the presence of abundant dietary fiber, resistant starch, and slowly digestible starch [28]. It is also a good source of micronutrients such as Fe, P, and niacin. Recently, many value-added products have been prepared using little millet to capitalize on the health benefits of little millet.

Table 1. Nutritional profile of millets in comparison with cereals (per 100 g).

| Grains | Energy (kcal) |

Protein (g) |

Carbohydrate (g) |

Starch (g) |

Fat(g) | Dietary Fiber (g) |

Minerals (g) |

Ca (mg) |

P (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorghum | 334 | 10.4 | 67.6 | 59 | 1.9 | 10.2 | 1.6 | 27 | 222 |

| Pearl millet | 363 | 11.6 | 61.7 | 55 | 5 | 11.4 | 2.3 | 27 | 296 |

| Finger millet | 320 | 7.3 | 66.8 | 62 | 1.3 | 11.1 | 2.7 | 364 | 283 |

| Proso millet | 341 | 12.5 | 70.0 | - | 1.1 | - | 1.9 | 14 | 206 |

| Foxtail millet | 331 | 12.3 | 60.0 | - | 4.3 | - | 3.3 | 31 | 290 |

| Kodo millet | 353 | 8.3 | 66.1 | 64 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 15 | 188 |

| Little millet | 329 | 8.7 | 65.5 | 56 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 17 | 220 |

| Barnyard millet | 307 | 11.6 | 65.5 | - | 5.8 | - | 4.7 | 14 | 121 |

| Maize | 334 | 11.5 | 64.7 | 59 | 3.6 | 12.2 | 1.5 | 8.9 | 348 |

| Wheat | 321 | 11.8 | 64.7 | 56 | 1.5 | 11.2 | 1.5 | 39 | 306 |

| Rice | 353 | 6.8 | 74.8 | 71 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 10 | 160 |

3. Antinutrient Profile of Millets

Antinutrients are phytochemical compounds that plants produce naturally for their defense. These antinutritional factors hinder nutrient absorption, leading to reduced nutrient bioavailability and utilization [31]. When consumed uncooked, products containing antinutrients and chemical compounds may be detrimental or even pose health issues in humans, such as micronutrient malnutrition, nutritional deficiency, and bloating. Plant-based foods mainly contain antinutrients such as tannins, phytates, oxalates, trypsin, and chymotrypsin inhibitors [32]. One of the disadvantages of millets is a higher concentration of antinutritional factors compared to wheat and rice. Finger millet contains polyphenols, tannins (0.61%), phytates (0.48%), trypsin inhibitors, and oxalates, which may interfere with the bioavailability of micronutrients and protein digestibility. The goitrogenic compounds in pearl millet are derivatives of phenolic flavonoids, such as C-glycosyl flavones, and their metabolites are responsible for the development of off-odors in the flour during storage [33]. Antinutritional factors due to metal chelation and enzyme inhibition capacity decrease nutrients bioavailability, mainly of minerals and proteins. However, in recent years, antinutritional factors such as polyphenolic compounds have been reported as nutraceuticals for their contribution to antioxidant properties [1]. Most secondary metabolites that function as antinutrients may cause extremely detrimental biological reactions, while others are actively used in nutrition and pharmacologically active drugs. The need of eliminating antinutrients is fulfilled by pretreatment or processing techniques of food grains, such as debranning, soaking, germination, fermentation, and autoclaving. These methods add value to food by enhancing the bioavailability of a few cations such as Ca, Fe, and Zn and also the proteins absorption [8].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods11040499

References

- Rao, D.B.; Malleshi, N.G.; Annor, G.A.; Patil, J.V. Nutritional and health benefits of millets. In Millets Value Chain for Nutritional Security: A Replicable Success Model from India; Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR): Hyderabad, India, 2017; p. 112.

- Ashoka, P.; Gangaiah, B.; Sunitha, N. Millets-foods of twenty first century. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 2404–2410.

- Nainwal, K. Conservation of minor millets for sustaining agricultural biodiversity and nutritional security. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, SP1, 1576–1580.

- Dutta, M.; Selvamani, Y.; Singh, P.; Prashad, L. The double burden of malnutrition among adults in India: Evidence from the national family health survey-4 (2015-16). Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, 11.

- Nithiyanantham, S.; Kalaiselvi, P.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Zengin, G.; Abirami, A.; Srinivasan, G. Nutritional and functional roles of millets—A review. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, 1–10.

- Annor, G.A.; Tyl, C.; Marcone, M.; Ragaee, S.; Marti, A. Why do millets have slower starch and protein digestibility than other cereals? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 66, 73–83.

- Anitha, S.; Govindaraj, M.; Kane-Potaka, J. Balanced amino acid and higher micronutrients in millets complements legumes for improved human dietary nutrition. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 74–84.

- Birania, S.; Rohilla, P.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, N. Post harvest processing of millets: A review on value added products. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 8, 1824–1829.

- Ramadoss, D.P.; Sivalingam, N. Vanillin extracted from Proso and Barnyard millets induce apoptotic cell death in HT-29 human colon cancer cell line. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 1422–1437.

- Yang, R.; Shan, S.; Zhang, C.; Shi, J.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Inhibitory Effects of Bound Polyphenol from Foxtail Millet Bran on Colitis-Associated Carcinogenesis by the Restoration of Gut Microbiota in a Mice Model. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 68, 3506–3517.

- Vedamanickam, R.; Anandan, P.; Bupesh, G.; Vasanth, S. Study of millet and non-millet diet on diabetics and associated metabolic syndrome. Biomedicine 2020, 40, 55–58.

- Hegde, P.S.; Rajasekaran, N.S.; Chandra, T.S. Effects of the antioxidant properties of millet species on oxidative stress and glycemic status in alloxan-induced rats. Nutr. Res. 2005, 25, 1109–1120.

- Ren, X.; Yin, R.; Hou, D.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Diao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Hu, X.; et al. The glucose-lowering effect of foxtail millet in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance: A self-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1509.

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Ren, Q. The Effect of Millet Porridge on the Gastrointestinal Function in Mice. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 6, 152–157.

- Gowda, N.N.; Taj, F.; Subramanya, S.; Ranganna, B. Development a table top centrifugal dehuller for small millets. AMA Agric. Mech. Asia Africa Latin Am. 2020, 51, 72–78.

- Anbukkani, P.; Balaji, S.J.; Nithyashree, M.L. Production and consumption of minor millets in India-a structural break analysis. Ann. Agric. Res. New Ser. 2017, 38, 1–8.

- DES-GOI. Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2020. In (Various Issues). Directorate of Economics and Statistics; Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2020.

- Nazni, S.; Devi, S. Effect of processing on the characteristics changes in barnyard and foxtail millet. J. Food Process. Technol. 2016, 7, 1–9.

- Sharma, N.; Niranjan, K. Foxtail millet: Properties, processing, health benefits, and uses. Food Rev. Int. 2018, 34, 329–363.

- Azad, M.O.K.; Jeong, D.I.; Adnan, M.; Salitxay, T.; Heo, J.W.; Naznin, M.T.; Lim, J.D.; Cho, D.H.; Park, B.J.; Park, C.H. Effect of different processing methods on the accumulation of the phenolic compounds and antioxidant profile of broomcorn millet (Panicum Miliaceum L.) Flour. Foods 2019, 8, 230.

- Chandrasekara, A.; Shahidi, F. Content of insoluble bound phenolics in millets and their contribution to antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6706–6714.

- Zhang, L.; Liu, R.; Niu, W. Phytochemical and antiproliferative activity of proso millet. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104058.

- Kalinova, J.; Moudry, J. Content and quality of protein in proso millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) varieties. Plant Foods. Hum. Nutr. 2006, 61, 45–49.

- Das, S.; Khound, R.; Santra, M.; Santra, D.K. Beyond bird feed: Proso millet for human health and environment. Agriculture 2019, 9, 64.

- Nambiar, V.S.; Dhaduk, J.J.; Sareen, N.; Shahu, T.; Desai, R. Potential functional implications of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) in health and disease. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 62–67.

- Gull, A.; Jan, R.; Nayik, G.A.; Prasad, K.; Kumar, P. Significance of finger millet in nutrition, health and value added products: A Review. J. Environ. Sci. Comput. Sci. Eng. Technol. Sect. C Eng. Technol. 2014, 3, 1601–1608.

- Neeharika, B.; Suneetha, W.J.; Kumari, B.A.; Tejashree, M. Organoleptic properties of ready to reconstitute little millet smoothie with fruit juices. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2020, 78–82.

- Patil, K.B.; Chimmad, B.V.; Itagi, S. Glycemic index and quality evaluation of little millet (Panicum miliare) flakes with enhanced shelf life. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6078–6082.

- NIN. Indian Food Compostion Tables; IIMR (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GoI): Hyderabad, India, 2017.

- IIMR. Nutritional and Health Benefits of Millets; Indian Institute of Millets Research: Hyderabad, India; ICAR: New Delhi, India, 2017.

- Bora, P.; Ragaee, S.; Marcone, M. Characterisation of several types of millets as functional food ingredients. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 714–724.

- Popova, A.; Mihaylova, D. Antinutrients in plant-based foods: A Review. Open Biotechnol. J. 2019, 13, 68–76.

- Taylor, J.R.N.; Emmambux, M.N. Gluten-free foods and beverages from millets. In Gluten-Free Cereal Products and Beverages; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 119–148.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!