Liver cancer is currently regarded as the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally and is the sixth most diagnosed malignancy. Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have attracted favorable attention as nanocarriers for gene therapy, as they possess beneficial antioxidant and anticancer properties. The study aimed to formulate, fully characterize SeNPs for their ability to bind, protect and efficiently deliver a luciferase reporter to liver cells in vitro. Targeted nanocomplexes showed significant transgene expression and were taken up into the cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Overall, these SeNPs showed good potential as gene or drug delivery vehicles.

1. Introduction

Liver cancer has the second-highest cancer-related mortality rate worldwide. It comprises heterogeneous groups of malignant tumors, which include hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA), mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CCA), fibrolamellar HCC (FLC) and paediatric neoplasm hepatoblastoma [

1,

2]. HCC is a primary liver cancer that stems from hepatocytes and accounts for 90% of all primary liver cancers [

3]. It is expected that over a million people will be affected annually by the year 2025 [

4]. Several pathways may be affected by HCC, including oxidative stress and detoxifying pathways, metabolism of iron pathways and DNA repair mechanisms [

5,

6]. Current cancer treatments include surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. However, these treatments have had minimal influence on reducing cancer mortality and become less effective if the tumor cells metastasize to other parts of the body [

7]. Furthermore, there are multiple obstacles associated with cancer treatments, including tumour heterogeneity, drug resistance and systematic toxicities throughout the body [

8,

9].

A promising form of treatment is gene therapy, which is used to correct or improve the symptoms of a disease by introducing an exogenous gene into cells that may modify a defective gene or initiate cell death. Gene therapy requires an efficient, safe and specific delivery system with a high gene insertion capacity and transfection rate and an administration method that is noninvasive or harmful [

10]. Inorganic nanoparticles are promising prospects as nonviral vectors. They possess numerous beneficial properties for cellular gene delivery, including efficient biocompatibility, storage stability, ease of preparation, wide availability, the potential of targeted delivery [

11] and low cytotoxicity [

12]. Interactions between nanoparticles (NPs) and biomolecules are essential for the successful loading and cellular transfection. Furthermore, for gene and drug delivery to achieve the desired success, novel strategies and pharmaceutical drug leads need to be developed [

13]. Nanomaterials in the form of NPs, nanofibers [

14] and spindles [

15] have been produced from organic and inorganic material. Several NPs have been utilized to date and have been generally classified as organic, carbon-based or inorganic NPs [

16]. Among the various inorganic NPs such as gold, silver, platinum, selenium and mesoporous silica that has been researched to date, selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have shown great potential in nanomedicine.

SeNPs have displayed increased biocompatibility and bioavailability that has matched other inorganic delivery vectors [

17,

18]. They possess low toxicity compared to various selenium compounds and exhibit potential therapeutic and diagnostic roles, thus making SeNPs likely elements for applications in clinical and biomedical fields [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. SeNPs have beneficial biological properties compared to inorganic and organic selenium compounds, as they have greater efficiency as a cofactor for thioredoxin reductase and glutathione peroxidase [

21,

25,

26,

27]. In addition to Se being an essential micronutrient, it is critical to normal body function, and its supplementation to treat various diseases have been recorded [

22]. Owing to these benefits, the application of SeNPs to liver-directed gene therapy may be a viable option, considering the possibility of synergistic therapeutic effects using SeNPs as delivery agents. SeNPs have been recently reported for the liver-directed delivery of mRNA [

28].

Uncoated SeNPs lack stability, which could affect the physicochemical characteristics of the NP [

29]. Surface modifications with a cationic surfactant allow for electrostatic interactions between an NP and a negatively charged biomolecule, e.g., DNA. Loading of the biomolecule is dependent on the charge density, modifier structure and length of the organic chain. The modifier may also protect the bound biomolecule [

26]. The SeNPs used in this study were functionalized and stabilized with poly-L-lysine (PLL). Lysine possesses attractive properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, hydrophobicity [

30], low toxicity and no antigenicity [

31]. Lysine residues bind to the surface of the SeNPs via electrostatic interactions due to the presence of two NH

3+ groups, providing greater stability and a cationic surface [

32]. Furthermore, the exposed NH

3+ groups on lysine residues allow electrostatic interaction and complex formation with nucleic acids [

19]. This makes PLL a suitable surface modification of inorganic NPs for gene delivery.

Cell specificity can be achieved by introducing a cell recognition component onto the NP surface, allowing the NP to enter the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME). Active targeting is accomplished by attaching targeting ligands on the surface of the NPs, enabling the NPs to bind to desired cognate receptors that are over-expressed on the target tumor cells and not expressed on normal cells [

33,

34]. The asialoorosomucoid receptor (ASGP-R) abundantly found on the surface of hepatocytes has a high affinity for ligands that contain terminal galactose residues [

35]. For efficient targeting of the asialoorosomucoid receptor (ASGP-R), the PLL–SeNPs was further modified with the galactose containing moiety, lactobionic acid (LA). The LA was conjugated onto the amino group of PLL via EDC/NHS coupling, followed by the introduction of the synthesized SeNPs to the newly formed LA–PLL coating, producing targeted LA–PLL–SeNPs. LA had been used successfully as a liver-targeting ligand in recent studies [

28,

36].

The use of PLL–SeNPs as nonviral gene delivery vehicles that can bind and protect their genetic cargo and bring about significant transgene expression has not been fully explored. Hence, this proof of principle study was designed to utilize these LA–PLL–SeNPs as liver-targeted delivery vehicles of the pCMV–Luc DNA reporter gene.

2. Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

The formation and functionalization of the SeNPs were first visually confirmed, with SeNPs appearing orange and the PLL-functionalized SeNPs displaying the characteristic red color, as reported previously [

37]. UV-vis and FTIR spectroscopy were further utilized to confirm the synthesis and functionalization of the SeNPs.

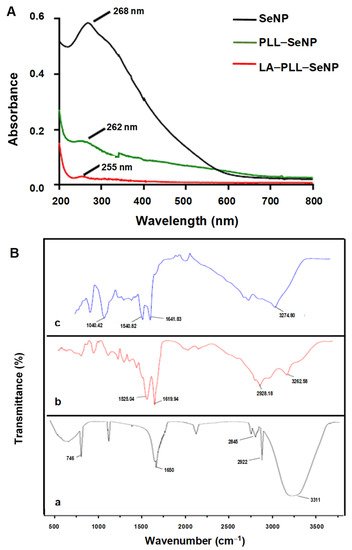

Figure 1A shows the UV-vis spectra of the synthesized NPs. All NPs possessed characteristic peaks with the SeNPs exhibiting a λmax at 268 nm. PLL–SeNP had a λmax at 262 nm, and LA–PLL–SeNP had a λmax at 255 nm, indicating a blue shift from the original SeNP upon each modification. Notably, the absorbance of the FSeNPs was much lower than that of the SeNPs.

Figure 1. (A) UV-vis spectra of SeNP, PLL–SeNP and LA–PLL–SeNP; (B) FTIR spectra of (a) SeNP, (b) PLL–SeNP and (c) LA–PLL–SeNP.

FTIR reflected the characteristic bands for the SeNPs and FSeNPs (

Figure 1B). The uncoated SeNPs (a) exhibited peaks at 3311 cm

−1, accounting for the hydroxyl group (−OH); two sharp peaks at 2845 cm

−1 and 2922 cm

−1; indicating C–H symmetric and asymmetric stretching respectively; and a peak at 1650 cm

−1, indicating the amide I of α-helical structures [

38]. A broad absorption peak was observed for PLL–SeNP (b) at 2928.18 cm

−1, indicating C–H stretching [

39]; at 3262.58 cm

−1, indicating an amide A; and two peaks at 1619.94 and 1525.04 cm

−1 corresponding to a β-sheet conformation of PLL on the SeNP surface [

40]. For the LA–PLL–SeNPs (c), there was a redshift in the amide A absorption peaks from 3262.58 cm

−1 to 3274.80 cm

−1, as well as for the amide I and II absorption peaks from 1619.94 and 1525.04 cm

−1 to 1641.83 and 1540.82 cm

−1, respectively. A distinct peak at 1040.42 cm

−1 indicated C−O stretching. This confirmed LA–PLL–SeNP synthesis.

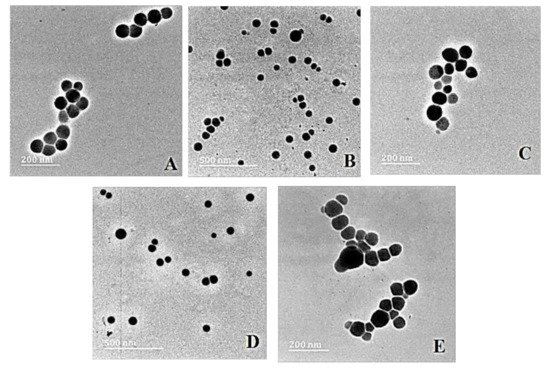

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provided the ultrastructural characteristics of the NPs and their nanocomplexes with pDNA, revealing spherical particles with no significant agglomeration (Figure 2).

Figure 2. TEM images of (A) SeNP, (B) PLL–SeNP, (C) LA–PLL–SeNP, (D) pDNA–PLL–SeNP and (E) pDNA–LA–PLL–SeNP. Scale Bar = 200 nm (A,C,E) and 500 nm (B,D).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was used to determine the size, zeta potential (ζ) and polydispersity of the NPs and nanocomplexes. The results (

Table 1) confirmed that the NPs and their nanocomplexes fell within the nanometer range (0–200 nm), which is considered a desirable feature for the use of NPs in nanomedicine [

41,

42]. The zeta potentials obtained alluded to NPs and nanocomplexes with moderate to good stability. The PDI values were all below 0.1, suggesting a monodisperse population.

Table 1. Nanoparticle and nanocomplex sizes, zeta potential and polydispersity index (PDI) from NTA. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 10).

| Nanoparticles |

Nanocomplexes |

| |

Size (nm) |

ζ Potential (mV) |

PDI |

pDNA:NP Ratio (w/w) |

Size (nm) |

ζ Potential (mV) |

PDI |

| SeNP |

75.7 ± 0.8 |

−12.1 ± 0.2 |

0.00011 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| PLL–SeNP |

84.7 ± 10 |

28.6 ± 10 |

0.014 |

1:2.7 |

118.7 ± 16.3 |

−26.9 ± 0.6 |

0.0189 |

| LA–PLL–SeNP |

124.3 ± 3.2 |

25.0 ± 6.3 |

0.00066 |

1:14 |

164.5 ± 77 |

−21.1 ± 0.3 |

0.0219 |

3. pDNA Binding and Cell-Based Assays

The band shift assay showed that both PLL-SeNP and LA-PLL-SeNP optimally bound the pDNA at varying ratios (Table 2). These NPs also protected the pDNA against nuclease digestion. Nanocomplexes exhibited no significant cytotoxicity on the HEK293, HeLa and HepG2 cells, in addition to little or no apoptosis observed. Significant gene expression was noted in all cell lines with a receptor competition assay confirming that the nanocomplexes entered the HepG2 cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis (Figure 3).

| Nanocomplex |

Optimal Binding Ratio (w/w) |

| PLL-SeNP:pDNA |

1:2.7 |

| LA-PLL-SeNP:pDNA |

1:14 |

Figure 3. Competition assay showing the transfection activity of LA-PLL-SeNP nanocomplexes in the HepG2 cells after blocking of the ASGP-R by excess LA. Data are represented as mean ±SD (n=3). **** (p < 0.0001) shows statistical significance between targeted nanocomplex without competitor vs targeted nanocomplexes with competitor (excess LA).

4. Overall Summary and Discussion

An ascorbic acid reduction successfully synthesized the SeNPs. Ascorbic acid’s biocompatibility and good reducing ability resulted in the formation of spherical NPs, with lower toxicity than that achieved using other reducing agents [

46]. The SeNPs were modified and stabilized with the cationic polymer, poly-L-lysine (PLL), which also conferred positive charges, and the ligand lactobionic acid (LA), which facilitated targeting of the asialoorosomucoid receptor (ASGP-R), over-expressed on hepatocytes (HepG2 cells). UV-vis spectroscopy confirmed the presence of the SeNPs (λmax = 268 nm) [

28] with the PLL and LA modified SeNPs displaying a blueshift in the spectrum, in addition to a drop in the absorbance. Capping agents influence the SPR, as it is the first material encountered on the NP. This encapsulation affects the electron oscillations around the NP, yielding variations in the SPR band [

39], as evidenced for the functionalized SeNPs.

NTA provides an insight into the NP’s potential to bind and compact the pDNA and their suitability as gene delivery vehicles. The NPs were below 125 nm while the nanocomplexes were below 170 nm in size, suggesting their potential for use as delivery vehicles since NPs below 200 nm have been reported as favorable delivery systems [

41,

42]. Liver-directed lipid-based delivery systems around 141 nm in diameter have shown targeted gene expression in parenchymal cells in vivo. In comparison, larger systems (>200 nm) seemed to achieve good gene expression in non-parenchymal cells [

47]. Furthermore, complexes >150 nm are restricted from traversing the liver tissue’s sinusoidal fenestrae [

48]. Hence, it is vital to reduce the size of the nanocomplexes to achieve enhanced ASGP-R-mediated targeting [

49]. The colloidal stability and the surface charge of the NPs are represented by the ζ potential [

41]. NPs with a ζ potential that falls within a range of <−25 mV and >+25 mV are considered to be colloidally stable [

50], boding well for in vivo applications. The addition of PLL to the SeNP surface resulted in greater stability of the NP with an increased ζ potential. However, the inclusion of LA to the PLL–SeNPs reduced the ζ potential and the positive charges on the NP, which could be attributed to the masking of positive charges of the PLL by the LA. The nanocomplexes all possessed low negative ζ potentials, which may be due to the nature of the pDNA conformation in the nanocomplex. It was noted that nanocomplexes <100 nm in size and with low zeta potentials (close to zero) were able to target the hepatocytes [

49] successfully. These nanocomplexes did show the ability to target the HepG2 cells in vitro. The PDI provides information on the size uniformity of the NPs, with PDI values below 0.1 being an indication of a monodisperse sample population. In contrast, PDI values greater than 0.4 indicate a polydisperse sample with a higher tendency to aggregate [

51]. Hence, these FSeNPs and their respective nanocomplexes were monodisperse with a low tendency to agglomerate.

Both PLL–SeNP and LA–PLL–SeNPs could efficiently bind and compact the pDNA, as evidenced by the electrophoretic mobility shift and dye displacement assays. The cationic nature of the PLL allowed for the electrostatic interaction of the anionic phosphate backbone of the pDNA with the protonated terminal lysine residues [

52]. This efficiently bound and compacted the pDNA and prevented its migration through the agarose gel. As the NP concentration increased, a point of electroneutrality was reached where the negative charges of the pDNA were completely neutralized by the positive charges of the NPs. This neutral state indicated the optimum binding ratio of the pDNA to the NP. A greater amount of the LA–PLL–SeNP than PLL–SeNP was required to bind the same amount of pDNA. As mentioned above, the LA may have shielded some of the positive charges of the PLL, leading to a reduction in the binding affinity of the targeted nanocomplex for the pDNA.

The ability of NPs to compact nucleic acids is important for gene delivery applications. Ethidium bromide (EB) is a fluorescent dye that intercalates between nucleic acids’ bases. It is important to note that the dye displacement assay provides information on the amount of the NP required to compact the pDNA, whereas the electrophoretic mobility shift assay indicates the minimum amount of the FSeNP needed to bind the pDNA. Although the targeted NPs produced a higher fluorescence decay than the untargeted NPs, there was a considerable difference in the amount of NPs needed to displace the EB. The targeted NPs required a higher amount than the untargeted NPs. This trend was also observed in the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. A lower concentration of the untargeted NPs may be needed since a longer segment of PLL can progressively condense more pDNA [

33]. The lower compaction of pDNA by the PLL–SeNP may be due to the conformation of the PLL encapsulating the SeNP. Since PLL may have existed primarily as β-sheets on the surface of the NP, it may have influenced the pDNA condensation as β-sheet conformations of PLL bound to NPs tend to aggregate [

24,

27,

53].

The FSeNPs were also capable of protecting the pDNA from degradation. However, most of the pDNA remained well-bound despite the use of SDS to liberate the pDNA. Similar results were found where SDS could not fully release the DNA from the nanocomplex were reported [

34,

54,

55]. The high compaction ability of the pDNA by the FSeNPs may have contributed to the inability of the SDS to release the pDNA from the nanocomplex fully. Hence, the pDNA remained in the wells.

The nanocomplexes further showed low or no cytotoxicity in vitro. Se is metabolized in the liver, accounting for the HepG2 cells displaying the highest cell viability of more than 80%. Furthermore, the kidney plays a role in the metabolism and excretion of seleno-species [

17,

38,

41,

43,

56,

57], which could explain the high cell viability of the HEK293 cells, as well. The cytotoxic effects of SeNPs have been previously reported [

22] and may be due to the concentration of sodium selenite. In the current study, a lower concentration of sodium selenite was used (0.005 M), resulting in negligible cytotoxic effects. The cytotoxicity of the SeNPs is also dependent on the concentration used [

17,

56,

58,

59]. Since low concentrations of the FSeNPs were required to bind the pDNA fully, no significant cytotoxicity was observed for the targeted and nontargeted SeNPs in all the three cell lines

The luciferase gene derived from the firefly (

Photinus pyralis) was used to evaluate transfection activity based on the evaluation of protein produced. Luminescence produced from the protein’s (luciferase enzyme) reaction with the substrate luciferin are measured and taken as being directly proportional to the concentration of the luciferase enzyme present [

57]. This is directly related to the number of cells that have been successfully transfected. The nanocomplex size can influence the cellular uptake efficiency as well as the pathway taken. Nanocomplexes that are between 120–150 nm in size are internalized via clathrin/caveolin mediated endocytosis [

31,

36,

60]. Since PLL–SeNP was smaller than the LA–PLL–SeNP, it allowed for sufficient cellular uptake across all cell lines. However, due to the inclusion of the targeting moiety, LA-mediated cellular uptake via RME was achieved since the LA–PLL–SeNPs were recognized by the abundantly expressed ASGP-R on the HepG2 cells. The HepG2 cells are good models for the ASGP-R as they have been reported to possess over 225,000 ASGP-Rs per cell [

61]. Wu and Wu [

62] were the first researchers to demonstrate ASGP-R-mediated gene delivery to HepG2 cells. They used a delivery system that included asialoorosomucoid cross-linked to PLL. In this study, the LA-mediated uptake occurred through a specific interaction with the galactose moiety of LA and the ASGP-R, which has a high affinity for terminal galactose moieties and N-acetylgalactosamine [

37,

49]. To confirm RME, the HepG2 cells were incubated with excess LA (25× more than that which is present on LA–PLL–SeNP), which blocked the ASGP-Rs, preventing recognition of the targeted nanocomplexes and ultimately decreasing overall luciferase activity for the targeted nanocomplexes. The use of chitosan modified SeNPs has shown successful targeted delivery of mRNA to HepG2 cells using LA as a targeting ligand [

28] and to KB cells using folate as the targeting ligand [

63]. In addition, they have recently shown successful delivery of pDNA in vitro [

64]. Overall, these PLL modified nanocomplexes were able to successfully bind, protect and deliver the pDNA in vitro, showing great promise in the use of these FSeNPs as nonviral gene delivery vehicles.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23031492