The whole milk product (and individual milk ingredients) from different species could impact cardiometabolic health.

- milk

- cardiometabolic health

- metabolism

- glycaemia

- energy expenditure

- appetite

- obesity

- type II diabetes

1. Introduction

The consumption of cow dairy products is a dominant feature in the diet of many cultures globally, particularly among Western communities. There is some evidence from epidemiological studies and systematic reviews alike that dairy intake is inversely linked with the risk of developing metabolic syndrome [1][2][3]. More pertinently, a body of data supports a negative association between milk intake and the risk of developing dysglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension [1][4]. However, with gold-standard data from long-term randomised controlled trials (RCTs) featuring type II diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence as primary endpoints not currently available, the causality of these findings remains to be confirmed [5]. Nonetheless, putative explanations for a possible metabolic syndrome risk reduction include a direct modulation of the glycaemic response [2][6], and an indirect modulation of body weight through upregulation of postprandial thermogenesis [6][7][8] and/or suppression of appetite [9][10][11]. Features of, or responses to, milk that might contribute to any cardiometabolic protection include the bioactive peptide content [12][13]; fatty acid (FA) content [14], e.g., conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) [15]; glycaemic index (GI) [16][17]; promotion of satiety [18]; mineral content, particularly calcium, magnesium, and potassium [19][20][21][22]; and folate bioavailability [23].

Although there is growing data on the acute and chronic health benefits of cow milk, albeit not yet conclusive, whether milk from alternative (non-bovine) sources could provide comparable or superior cardiometabolic protection has not yet been comprehensively reviewed.

2. Current Status of Cow Milk Alternatives

The worldwide commercial production of cow milk decisively eclipses the relatively minor contributions from alternative animal species (Table 1). Nonetheless, these milks remain valuable primary sources for many countries and communities globally.

Table 1. Mean contribution of individual species’ milks towards global production. [24]

| Milk Origin | Global Milk Production (%) | Global Milk Production (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Cow | 81.3 | 714,400,000,000 |

| Buffalo | 14.8 | 130,300,000,000 |

| Goat | 2.2 | 18,900,000,000 |

| Sheep | 1.3 | 11,800,000,000 |

| Camel | 0.4 | 3,200,000,000 |

Values rounded to nearest 0.1 percent or 109 kg.

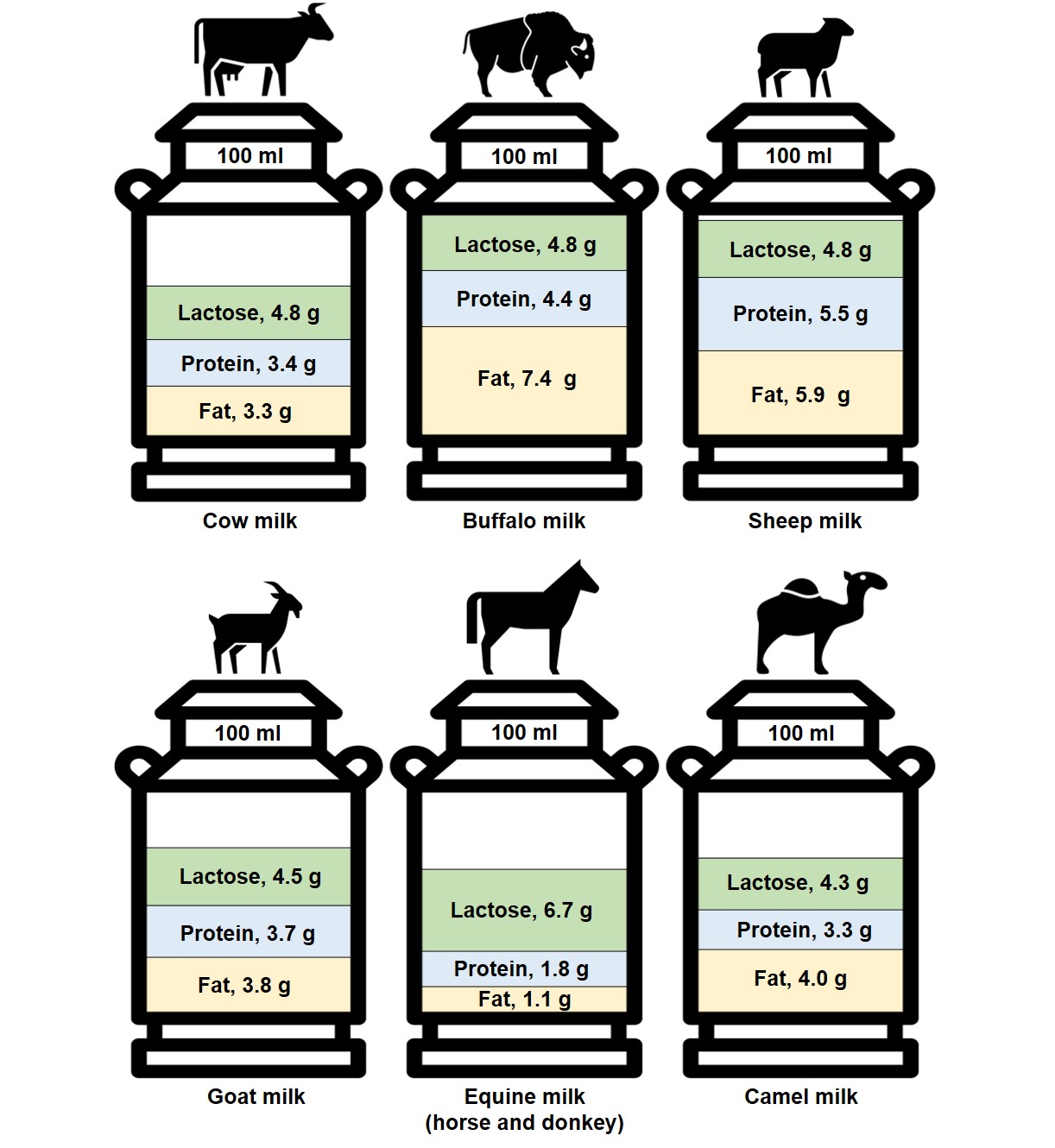

Owing to the specific make-up of proteins (e.g., β-lactoglobulin; β-lg) and sugars (e.g., lactose) within cow milk, the global prevalence of cow milk allergy and intolerance is notably high. Approximately 65% of adults worldwide have a suboptimal capacity to digest and absorb lactose [25]. In Asian and American Indian populations, the reported prevalence of lactose intolerance is closer to 100% [26][27]. However, with marked compositional differences (see Figure 1), hypoallergenicity and improved tolerability have been indicated following the ingestion of goat [28], sheep [29], camel [30], buffalo [31], and donkey [32] milk, as compared to cow milk. It should be noted that throughout this review buffalo milk refers to the produce of animals of the Bubalus genus.

Lastly, non-dairy substitutes for milk, including soy, oat, rice, and nut ‘milk beverages’ have received growing attention. These plant-based alternatives are formulated through the disintegration of plant material, extraction in water, and subsequent homogenisation, which produces a ‘milk’ reminiscent of the consistency and appearance of animal milk [33]. Despite a typically substandard macronutrient profile relative to mammalian milk, plant-based ‘milks’ possess distinct functional ingredients, lower allergenicity and greater affordability, which have impelled a noticeable surge in demand and production.

Figure 1. The composition of different species’ milk by fat, protein, and lactose content per 100 mL [22][29][34][35]. Equine milk values represent the mean nutrient content in mare and donkey milks.

3. Application to Cardiometabolic Health

3.1. Influence of Milk Origin on Energy Balance & Obesity

3.1.1. Appetite Regulation

3.1.2. Energy Expenditure

3.1.3 Nutrient Processing

3.1.4. Body Weight and Composition

3.2 Influence of Milk Origin on Insulinaemia, Glycaemia, and Type II Diabetes

3.2.1. Insulinaemia

3.2.2 Glycaemia

3.2.3. Type II Diabetes

3.3. Influence of Milk Origin on Cardiovascular Health

4. Conclusions

The effect of milk origin on cardiometabolic health is an emerging area of research. There is some data, although primarily from compositional analyses [35][144], in vitro studies [145], animal studies [146], and acute clinical RCTs [147][148][149], that milk from non-bovine origin (notably sheep and goat milk) could prove to be a viable substitute to cow milk for the maintenance, or even enhancement, of cardiometabolic health. However, a collation of the compositional differences and postulated therapeutic utility, indicate that the level of evidence required to form nutritional recommendations surrounding milk origin is currently lacking. Nonetheless, there are some interesting results, albeit largely from preliminary studies, that have generated excitement around sheep milk consumption for the possible attenuation of cardiometabolic risk. This interest is largely based upon its favourable profile of lipids (for example, MCTs, CLA), protein (for example,, leucine), and minerals (for example, calcium). In theory, these compounds could provide protection from obesity, T2D, and CVD through the modulation of postprandial glycaemia, lipidaemia and aminoacidaemia; nutrient processing; postprandial thermogenesis; and/or appetite. Comparably, with desirable nutritional compositions and some promising early findings, goat and buffalo milk may also prove to be robust alternatives to cow milk. However, as with sheep milk, there is currently a stark absence of high-quality research in humans. Hence, as remains pertinent for cow milk, to substantiate any claims that the consumption of cow-milk alternatives can improve cardiometabolic health, causal data from long-term clinical RCTs, ideally with T2D and/or CVD events as the primary endpoint, are required. Evidence from large-scale studies that support the conjectures formed could not only be of value to individuals allergic or intolerant to cow milk, but potentially also to those at an increased risk of cardiometabolic disease.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14020290

References

- Pereira, M.A.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Van Horn, L.; Slattery, M.L.; Kartashov, A.I.; Ludwig, D.S. Dairy consumption, obesity, and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: The CARDIA Study. JAMA 2002, 287, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, R.A.; Poppitt, S.D. Milk protein for improved metabolic health: A review of the evidence. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Chen, C.; Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Jacobs, D.R.; Shikany, J.M.; Kahe, K. Calcium Intake Is Inversely Related to Risk of Obesity among American Young Adults over a 30-Year Follow-Up. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2383–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorning, T.K.; Raben, A.; Tholstrup, T.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Givens, I.; Astrup, A. Milk and dairy products: Good or bad for human health? An assessment of the totality of scientific evidence. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppitt, S.D. Cow’s Milk and Dairy Consumption: Is There Now Consensus for Cardiometabolic Health? Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 574725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheson, K.J.; Blondel-Lubrano, A.; Oguey-Araymon, S.; Beaumont, M.; Emady-Azar, S.; Ammon-Zufferey, C.; Monnard, I.; Pinaud, S.; Nielsen-Moennoz, C.; Bovetto, L. Protein choices targeting thermogenesis and metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, H.; Steiniger, J.; Noack, R.; Steglich, H.D. Diet-induced thermogenesis in man: Thermic effects of single proteins, carbohydrates and fats depending on their energy amount. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 1984, 28, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzen, J.; Frederiksen, R.; Hoppe, C.; Hvid, R.; Astrup, A. The effect of milk proteins on appetite regulation and diet-induced thermogenesis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; James, A.; Flint, A.; Astrup, A. Increased satiety after intake of a chocolate milk drink compared with a carbonated beverage, but no difference in subsequent ad libitum lunch intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhorst, M.A.; Nieuwenhuizen, A.G.; Hochstenbach-Waelen, A.; van Vught, A.J.; Westerterp, K.R.; Engelen, M.P.; Brummer, R.J.; Deutz, N.E.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Dose-dependent satiating effect of whey relative to casein or soy. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 96, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Joanisse, D.R.; Chaput, J.P.; Miegueu, P.; Cianflone, K.; Almeras, N.; Tremblay, A. Milk supplementation facilitates appetite control in obese women during weight loss: A randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, I.; Artacho, R.; Olalla, M. Milk protein peptides with angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory (ACEI) activity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.C. Milk nutritional composition and its role in human health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjogren, P.; Rosell, M.; Skoglund-Andersson, C.; Zdravkovic, S.; Vessby, B.; de Faire, U.; Hamsten, A.; Hellenius, M.L.; Fisher, R.M. Milk-derived fatty acids are associated with a more favorable LDL particle size distribution in healthy men. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whigham, L.D.; Watras, A.C.; Schoeller, D.A. Efficacy of conjugated linoleic acid for reducing fat mass: A meta-analysis in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.; Leeds, A.A.; Dore, C.J.; Madeiros, S.; Brading, S.; Dornhorst, A. Glycaemic index as a determinant of serum HDL-cholesterol concentration. Lancet 1999, 353, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, F.S.; Brand-Miller, J.C.; Foster-Powell, K.; Buyken, A.E.; Goletzke, J. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values 2021: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maersk, M.; Belza, A.; Holst, J.J.; Fenger-Gron, M.; Pedersen, S.B.; Astrup, A.; Richelsen, B. Satiety scores and satiety hormone response after sucrose-sweetened soft drink compared with isocaloric semi-skimmed milk and with non-caloric soft drink: A controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iso, H.; Stampfer, M.J.; Manson, J.E.; Rexrode, K.; Hennekens, C.H.; Colditz, G.A.; Speizer, F.E.; Willett, W.C. Prospective study of calcium, potassium, and magnesium intake and risk of stroke in women. Stroke 1999, 30, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Folsom, A.R.; Melnick, S.L.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Sharrett, A.R.; Nabulsi, A.A.; Hutchinson, R.G.; Metcalf, P.A. Associations of serum and dietary magnesium with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, insulin, and carotid arterial wall thickness: The ARIC study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, L.K. Dairy food consumption, blood pressure and stroke. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, W.; Verraes, C.; Cardoen, S.; De Block, J.; Huyghebaert, A.; Raes, K.; Dewettinck, K.; Herman, L. Consumption of raw or heated milk from different species: An evaluation of the nutritional and potential health benefits. Food Control. 2014, 42, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeuffer, M.; Schrezenmeir, J. Milk and the metabolic syndrome. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAOSTAT Statistics Database. 2018. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Itan, Y.; Jones, B.L.; Ingram, C.J.; Swallow, D.M.; Thomas, M.G. A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, T.D.; Crane, G.G.; Davis, A.E. Lactose intolerance in various ethnic groups in South-East Asia. Australas. Ann. Med. 1968, 17, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, T. Genetics and epidemiology of adult-type hypolactasia. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1994, 202, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W. Overview of Bioactive Components in Milk and Dairy Products. In Bioactive Components in Milk and Dairy Products; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar, C.F.; Pimentel, T.C.; Ferrao, L.L.; Almada, C.N.; Santillo, A.; Albenzio, M.; Mollakhalili, N.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Nascimento, J.S.; Silva, M.C.; et al. Sheep Milk: Physicochemical Characteristics and Relevance for Functional Food Development. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Agamy, E.I.; Nawar, M.; Shamsia, S.M.; Awad, S.; Haenlein, G.F. Are camel milk proteins convenient to the nutrition of cow milk allergic children? Small Rumin. Res. 2009, 82, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, W.J.; Phipatanakul, W. Tolerance to water buffalo milk in a child with cow milk allergy. Ann. Allergy Asthma. Immunol. 2009, 102, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroccio, A.; Cavataio, F.; Montalto, G.; D’Amico, D.; Alabrese, L.; Iacono, G. Intolerance to hydrolysed cow’s milk proteins in infants: Clinical characteristics and dietary treatment. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2000, 30, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, S.; Tyagi, S.K.; Anurag, R.K. Plant-based milk alternatives an emerging segment of functional beverages: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3408–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhammar, E.; Wijesinha-Bettoni, R.; Stadlmayr, B.; Nilsson, E.; Charrondiere, U.R.; Burlingame, B. Composition of milk from minor dairy animals and buffalo breeds: A biodiversity perspective. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 445–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barłowska, J.; Szwajkowska, M.; Litwińczuk, Z.; Król, J. Nutritional value and technological suitability of milk from various animal species used for dairy production. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Martin, E.; Garcia-Escobar, E.; Ruiz de Adana, M.S.; Lima-Rubio, F.; Pelaez, L.; Caracuel, A.M.; Bermudez-Silva, F.J.; Soriguer, F.; Rojo-Martinez, G.; Olveira, G. Comparison of the Effects of Goat Dairy and Cow Dairy Based Breakfasts on Satiety, Appetite Hormones, and Metabolic Profile. Nutrients 2017, 9, 877.

- Milan, A.M.; Hodgkinson, A.J.; Mitchell, S.M.; Prodhan, U.K.; Prosser, C.G.; Carpenter, E.A.; Fraser, K.; Cameron-Smith, D. Digestive Responses to Fortified Cow or Goat Dairy Drinks: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1492.

- Alferez, M.J.; Barrionuevo, M.; Lopez Aliaga, I.; Sanz-Sampelayo, M.R.; Lisbona, F.; Robles, J.C.; Campos, M.S. Digestive utilization of goat and cow milk fat in malabsorption syndrome. J. Dairy Res. 2001, 68, 451–461.

- Sanchez-Moya, T.; Planes-Munoz, D.; Frontela-Saseta, C.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Lopez-Nicolas, R. Milk whey from different animal species stimulates the in vitro release of CCK and GLP-1 through a whole simulated intestinal digestion. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7208–7216.

- Uchida, M.; Ohshiba, Y.; Mogami, O. Novel dipeptidyl peptidase-4-inhibiting peptide derived from beta-lactoglobulin. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 117, 63–66.

- Tulipano, G.; Cocchi, D.; Caroli, A.M. Comparison of goat and sheep β-lactoglobulin to bovine β-lactoglobulin as potential source of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-4) inhibitors. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 24, 97–101.

- Vargas-Bello-Perez, E.; Marquez-Hernandez, R.I.; Hernandez-Castellano, L.E. Bioactive peptides from milk: Animal determinants and their implications in human health. J. Dairy Res. 2019, 86, 136–144.

- Luhovyy, B.L.; Akhavan, T.; Anderson, G.H. Whey proteins in the regulation of food intake and satiety. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 704S–712S.

- Bendtsen, L.Q.; Lorenzen, J.K.; Bendsen, N.T.; Rasmussen, C.; Astrup, A. Effect of dairy proteins on appetite, energy expenditure, body weight, and composition: A review of the evidence from controlled clinical trials. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 418–438.

- St-Onge, M.P.; Jones, P.J. Physiological effects of medium-chain triglycerides: Potential agents in the prevention of obesity. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 329–332.

- Ceballos, L.S.; Morales, E.R.; Martinez, L.P.; Extremera, F.G.; Sampelayo, M.R. Utilization of nitrogen and energy from diets containing protein and fat derived from either goat milk or cow milk. J. Dairy Res. 2009, 76, 497–504.

- Seaton, T.B.; Welle, S.L.; Warenko, M.K.; Campbell, R.G. Thermic effect of medium-chain and long-chain triglycerides in man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 44, 630–634.

- Scalfi, L.; Coltorti, A.; Contaldo, F. Postprandial thermogenesis in lean and obese subjects after meals supplemented with medium-chain and long-chain triglycerides. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 53, 1130–1133.

- Matsuo, T.; Matsuo, M.; Taguchi, N.; Takeuchi, H. The thermic effect is greater for structured medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols versus long-chain triacylglycerols in healthy young women. Metabolism 2001, 50, 125–130.

- Dulloo, A.G.; Fathi, M.; Mensi, N.; Girardier, L. Twenty-four-hour energy expenditure and urinary catecholamines of humans consuming low-to-moderate amounts of medium-chain triglycerides: A dose-response study in a human respiratory chamber. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 50, 152–158.

- Hill, J.O.; Peters, J.C.; Yang, D.; Sharp, T.; Kaler, M.; Abumrad, N.N.; Greene, H.L. Thermogenesis in humans during overfeeding with medium-chain triglycerides. Metabolism 1989, 38, 641–648.

- Matsuo, T.; Takeuchi, H. Effects of structured medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols in diets with various levels of fat on body fat accumulation in rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 91, 219–225.

- Haenlein, G. Goat milk in human nutrition. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 51, 155–163.

- Lasekan, J.B.; Rivera, J.; Hirvonen, M.D.; Keesey, R.E.; Ney, D.M. Energy expenditure in rats maintained with intravenous or intragastric infusion of total parenteral nutrition solutions containing medium- or long-chain triglyceride emulsions. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 1483–1492.

- Posati, L.P.; Orr, M.L. Composition of Foods—Dairy and Egg Products: Raw, Processed, Prepared; Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture: Beltsville, MD, USA, 1976.

- Acheson, K.J.; Blondel-Lubrano, A.; Oguey-Araymon, S.; Beaumont, M.; Emady-Azar, S.; Ammon-Zufferey, C.; Monnard, I.; Pinaud, S.; Nielsen-Moennoz, C.; Bovetto, L. Protein choices targeting thermogenesis and metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 525–534.

- Boirie, Y.; Dangin, M.; Gachon, P.; Vasson, M.P.; Maubois, J.L.; Beaufrere, B. Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 14930–14935.

- Ravussin, E.; Lillioja, S.; Anderson, T.E.; Christin, L.; Bogardus, C. Determinants of 24-hour energy expenditure in man. Methods and results using a respiratory chamber. J. Clin. Investig. 1986, 78, 1568–1578.

- Claeys, W.; Verraes, C.; Cardoen, S.; De Block, J.; Huyghebaert, A.; Raes, K.; Dewettinck, K.; Herman, L. Consumption of raw or heated milk from different species: An evaluation of the nutritional and potential health benefits. Food Control. 2014, 42, 188–201.

- Layman, D.K. The role of leucine in weight loss diets and glucose homeostasis. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 261S–267S.

- Smilowitz, J.T.; Dillard, C.J.; German, J.B. Milk beyond essential nutrients: The metabolic food. Aust. J. Dairy Technol. 2005, 60, 77.

- Zemel, M.B.; Shi, H.; Greer, B.; Dirienzo, D.; Zemel, P.C. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 1132–1138.

- Zemel, M.B.; Richards, J.; Milstead, A.; Campbell, P. Effects of calcium and dairy on body composition and weight loss in African-American adults. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 1218–1225.

- Booth, A.O.; Huggins, C.E.; Wattanapenpaiboon, N.; Nowson, C.A. Effect of increasing dietary calcium through supplements and dairy food on body weight and body composition: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1013–1025.

- Mohammad, M.A.; Sunehag, A.L.; Rodriguez, L.A.; Haymond, M.W. Galactose promotes fat mobilization in obese lactating and nonlactating women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 374–381.

- Thorning, T.K.; Raben, A.; Tholstrup, T.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Givens, I.; Astrup, A. Milk and dairy products: Good or bad for human health? An assessment of the totality of scientific evidence. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32527.

- Mack, P. A preliminary nutrition study of the value of goat’s milk in the diet of children. In Yearbook of the American Goat Society; American Goat Society, Inc.: Mena, AR, USA, 1952.

- Razafindrakoto, O.; Ravelomanana, N.; Rasolofo, A.; Rakotoarimanana, R.D.; Gourgue, P.; Coquin, P.; Briend, A.; Desjeux, J.F. Goat’s milk as a substitute for cow’s milk in undernourished children: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Pediatrics 1994, 94, 65–69.

- Lejeune, M.P.; Kovacs, E.M.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Additional protein intake limits weight regain after weight loss in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 281–289.

- Park, Y.; Juárez, M.; Ramos, M.; Haenlein, G. Physico-chemical characteristics of goat and sheep milk. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 68, 88–113.

- Guo, H.Y.; Pang, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, S.W.; Dong, M.L.; Ren, F.Z. Composition, physiochemical properties, nitrogen fraction distribution, and amino acid profile of donkey milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 1635–1643.

- Park, Y. Rheological characteristics of goat and sheep milk. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 68, 73–87.

- Shamsia, S. Nutritional and therapeutic properties of camel and human milks. Int. J. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2009, 1, 052–058.

- Kanwal, R.; Ahmed, T.; Mirza, B. Comparative analysis of quality of milk collected from buffalo, cow, goat and sheep of Rawalpindi/Islamabad region in Pakistan. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2004, 3, 300–305.

- Barłowska, J. Nutritional Value and Technological Usability of Milk From Cows of 7 Breeds Maintained in Poland. Postdoctoral Thesis, Agriculture Academy, University of Life Sciences, Lublin, Poland, 2007.

- Mohapatra, A.; Shinde, A.K.; Singh, R. Sheep milk: A pertinent functional food. Small Rumin. Res. 2019, 181, 6–11.

- Pfeuffer, M.; Schrezenmeir, J. Milk and the metabolic syndrome. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 109–118.

- McGregor, R.A.; Poppitt, S.D. Milk protein for improved metabolic health: A review of the evidence. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 46.

- Ha, E.; Zemel, M.B. Functional properties of whey, whey components, and essential amino acids: Mechanisms underlying health benefits for active people (review). J. Nutr. Biochem 2003, 14, 251–258.

- Master, P.B.Z.; Macedo, R.C.O. Effects of dietary supplementation in sport and exercise: A review of evidence on milk proteins and amino acids. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1225–1239.

- Astrup, A. The satiating power of protein—A key to obesity prevention? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 1–2.

- Leidy, H.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Astrup, A.; Wycherley, T.P.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Woods, S.C.; Mattes, R.D. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1320S–1329S.

- Kim, J.E.; O’Connor, L.E.; Sands, L.P.; Slebodnik, M.B.; Campbell, W.W. Effects of dietary protein intake on body composition changes after weight loss in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 210–224.

- Hansen, T.T.; Astrup, A.; Sjodin, A. Are Dietary Proteins the Key to Successful Body Weight Management? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Assessing Body Weight Outcomes after Interventions with Increased Dietary Protein. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3193.

- Barłowska, J.; Szwajkowska, M.; Litwińczuk, Z.; Król, J. Nutritional value and technological suitability of milk from various animal species used for dairy production. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 291–302.

- Berrazaga, I.; Micard, V.; Gueugneau, M.; Walrand, S. The Role of the Anabolic Properties of Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Sources in Supporting Muscle Mass Maintenance: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1825.

- Scholz-Ahrens, K.E.; Ahrens, F.; Barth, C.A. Nutritional and health attributes of milk and milk imitations. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 19–34.

- van Vliet, S.; Burd, N.A.; van Loon, L.J. The Skeletal Muscle Anabolic Response to Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Consumption. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1981–1991.

- Poppitt, S.D. Milk proteins and human health. In Milk Proteins; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 651–669.

- Balthazar, C.F.; Pimentel, T.C.; Ferrao, L.L.; Almada, C.N.; Santillo, A.; Albenzio, M.; Mollakhalili, N.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Nascimento, J.S.; Silva, M.C.; et al. Sheep Milk: Physicochemical Characteristics and Relevance for Functional Food Development. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 247–262.

- Marten, B.; Pfeuffer, M.; Schrezenmeir, J. Medium-chain triglycerides. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 1374–1382.

- Recio, I.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Juárez, M.; Ramos, M. Bioactive components in sheep milk. In Bioactive Components in Milk and Dairy Products; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 83–104.

- Zemel, M.B.; Teegarden, D.; Van Loan, M.; Schoeller, D.; Matkovic, V.; Lyle, R.; Craig, B. Role of dairy products in modulating weight and fat loss: A multi-center trial. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 4–5.

- Zemel, M.B. Role of calcium and dairy products in energy partitioning and weight management. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 907S–912S.

- Nuttall, F.Q.; Gannon, M.C. Quantitative importance of dietary constituents other than glucose as insulin secretagogues in type II diabetes. Diabetes Care 1988, 11, 72–76.

- Coe, S.; Ryan, L. Impact of polyphenol-rich sources on acute postprandial glycaemia: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e24.

- Gunnerud, U.; Holst, J.J.; Ostman, E.; Bjorck, I. The glycemic, insulinemic and plasma amino acid responses to equi-carbohydrate milk meals, a pilot- study of bovine and human milk. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 83.

- Floyd, J.C., Jr.; Fajans, S.S.; Conn, J.W.; Knopf, R.F.; Rull, J. Stimulation of insulin secretion by amino acids. J. Clin. Investig. 1966, 45, 1487–1502.

- van Loon, L.J.; Saris, W.H.; Verhagen, H.; Wagenmakers, A.J. Plasma insulin responses after ingestion of different amino acid or protein mixtures with carbohydrate. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 96–105.

- Jakubowicz, D.; Froy, O. Biochemical and metabolic mechanisms by which dietary whey protein may combat obesity and Type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. Biochem 2013, 24, 1–5.

- Frid, A.H.; Nilsson, M.; Holst, J.J.; Bjorck, I.M. Effect of whey on blood glucose and insulin responses to composite breakfast and lunch meals in type 2 diabetic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 69–75.

- Jakubowicz, D.; Froy, O.; Ahren, B.; Boaz, M.; Landau, Z.; Bar-Dayan, Y.; Ganz, T.; Barnea, M.; Wainstein, J. Incretin, insulinotropic and glucose-lowering effects of whey protein pre-load in type 2 diabetes: A randomised clinical trial. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1807–1811.

- Comerford, K.B.; Pasin, G. Emerging Evidence for the Importance of Dietary Protein Source on Glucoregulatory Markers and Type 2 Diabetes: Different Effects of Dairy, Meat, Fish, Egg, and Plant Protein Foods. Nutrients 2016, 8, 446.

- Pietrzak-Fiecko, R.; Kamelska-Sadowska, A.M. The Comparison of Nutritional Value of Human Milk with other Mammals’ Milk. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1404.

- Sun, L.; Tan, K.W.J.; Han, C.M.S.; Leow, M.K.; Henry, C.J. Impact of preloading either dairy or soy milk on postprandial glycemia, insulinemia and gastric emptying in healthy adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 56, 77–87.

- Sun, L.; Tan, K.W.; Siow, P.C.; Henry, C.J. Soya milk exerts different effects on plasma amino acid responses and incretin hormone secretion compared with cows’ milk in healthy, young men. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 1216–1221.

- Agrawal, R.; Singh, G.; Nayak, K.; Kochar, D.; Sharma, R.; Beniwal, R.; Rastogi, P.; Gupta, R. Prevalence of diabetes in camel-milk consuming Raica rural community of north-west Rajasthan. Int. J. Diab. Dev. Ctries. 2004, 24, 109–114.

- Yagil, R.; Zagorski, O.; Van Creveld, C.; Saran, A. Science and Camel’s Milk Production. In Proceedings of the Chameux et Dromedaries, Animaux Laitiers (Dromedaries and Camels, Milking Animals); Saint Martin, G., Ed.; Expansion Scientifique Francais: Paris, France; pp. 75–89. Available online: https://bengreenfieldfitness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Science-and-camel%E2%80%99s-milk-production.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Zagorski, O.; Maman, A.; Yaffe, A.; Meisler, A.; Van Creveld, C.; Yagil, R. Insulin in milk-a comparative study. Int. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 13, 241–244.

- Agrawal, R.P.; Jain, S.; Shah, S.; Chopra, A.; Agarwal, V. Effect of camel milk on glycemic control and insulin requirement in patients with type 1 diabetes: 2-years randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1048–1052.

- Cano, M.P.G.; Van Nieuwenhove, C.; Chaila, Z.; Bazan, C.; Gonzalez, S. Effects of short-term mild calorie restriction diet and renutrition with ruminant milks on leptin levels and other metabolic parameters in mice. Nutrition 2009, 25, 322–329.

- Belury, M.; Vanden Heuvel, J. Modulation of diabetes by conjugated linoleic acid. Adv. Conjug. Linoleic Acid Res. 1999, 1, 404–411.

- Poppitt, S.D. Cow’s Milk and Dairy Consumption: Is There Now Consensus for Cardiometabolic Health? Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 574725.

- Li, K.; Sinclair, A.J.; Zhao, F.; Li, D. Uncommon Fatty Acids and Cardiometabolic Health. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1559.

- Riserus, U.; Arner, P.; Brismar, K.; Vessby, B. Treatment with dietary trans10cis12 conjugated linoleic acid causes isomer-specific insulin resistance in obese men with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1516–1521.

- Ryder, J.W.; Portocarrero, C.P.; Song, X.M.; Cui, L.; Yu, M.; Combatsiaris, T.; Galuska, D.; Bauman, D.E.; Barbano, D.M.; Charron, M.J.; et al. Isomer-specific antidiabetic properties of conjugated linoleic acid. Improved glucose tolerance, skeletal muscle insulin action, and UCP-2 gene expression. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1149–1157.

- Atkinson, F.S.; Brand-Miller, J.C.; Foster-Powell, K.; Buyken, A.E.; Goletzke, J. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values 2021: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1625–1632.

- Foster-Powell, K.; Miller, J.B. International tables of glycemic index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 62, 871S–890S.

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.; Taylor, R.H.; Barker, H.; Fielden, H.; Baldwin, J.M.; Bowling, A.C.; Newman, H.C.; Jenkins, A.L.; Goff, D.V. Glycemic index of foods: A physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 362–366.

- Jeske, S.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Evaluation of Physicochemical and Glycaemic Properties of Commercial Plant-Based Milk Substitutes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 26–33.

- Cataldi, T.R.; Angelotti, M.; Bianco, G. Determination of mono-and disaccharides in milk and milk products by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2003, 485, 43–49.

- Ercan, N.; Nuttall, F.Q.; Gannon, M.C.; Redmon, J.B.; Sheridan, K.J. Effects of glucose, galactose, and lactose ingestion on the plasma glucose and insulin response in persons with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1993, 42, 1560–1567.

- Pereira, M.A.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Van Horn, L.; Slattery, M.L.; Kartashov, A.I.; Ludwig, D.S. Dairy consumption, obesity, and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: The CARDIA Study. JAMA 2002, 287, 2081–2089.

- Aune, D.; Norat, T.; Romundstad, P.; Vatten, L.J. Dairy products and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1066–1083.

- Huth, P.J.; Park, K.M. Influence of dairy product and milk fat consumption on cardiovascular disease risk: A review of the evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 266–285.

- Riserus, U.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Dietary fats and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Prog. Lipid Res. 2009, 48, 44–51.

- Lordan, R.; Zabetakis, I. Invited review: The anti-inflammatory properties of dairy lipids. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 4197–4212.

- Astrup, A.; Magkos, F.; Bier, D.M.; Brenna, J.T.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Hill, J.O.; King, J.C.; Mente, A.; Ordovas, J.M.; Volek, J.S.; et al. Saturated Fats and Health: A Reassessment and Proposal for Food-Based Recommendations: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 844–857.

- Paszczyk, B.; Tońska, E.; Łuczyńska, J. Health-promoting value of cow, sheep and goat milk and yogurts. Mljekarstvo Časopis Za Unaprjeđenje Proizv. I Prerade Mlijeka 2019, 69, 182–192.

- Salamon, R.; Salamon, S.; Csapó-Kiss, Z.; Csapó, J. Composition of mare’s colostrum and milk I. Fat content, fatty acid composition and vitamin contents. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Aliment. 2009, 2, 119–131.

- Barreto, Í.M.L.G.; Rangel, A.H.d.N.; Urbano, S.A.; Bezerra, J.d.S.; Oliveira, C.A.d.A. Equine milk and its potential use in the human diet. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 1–7.

- Sowers, J.R.; Epstein, M.; Frohlich, E.D. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: An update. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1053–1059.

- Tuomilehto, J.; Lindstrom, J.; Hyyrynen, J.; Korpela, R.; Karhunen, M.L.; Mikkola, L.; Jauhiainen, T.; Seppo, L.; Nissinen, A. Effect of ingesting sour milk fermented using Lactobacillus helveticus bacteria producing tripeptides on blood pressure in subjects with mild hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2004, 18, 795–802.

- Turpeinen, A.M.; Ikonen, M.; Kivimaki, A.S.; Kautiainen, H.; Vapaatalo, H.; Korpela, R. A spread containing bioactive milk peptides Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro, and plant sterols has antihypertensive and cholesterol-lowering effects. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 621–627.

- Turpeinen, A.M.; Jarvenpaa, S.; Kautiainen, H.; Korpela, R.; Vapaatalo, H. Antihypertensive effects of bioactive tripeptides-a random effects meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2013, 45, 51–56.

- Minervini, F.; Algaron, F.; Rizzello, C.G.; Fox, P.F.; Monnet, V.; Gobbetti, M. Angiotensin I-converting-enzyme-inhibitory and antibacterial peptides from Lactobacillus helveticus PR4 proteinase-hydrolyzed caseins of milk from six species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5297–5305.

- Politis, I.; Theodorou, G. Angiotensin I-converting (ACE)-inhibitory and anti-inflammatory properties of commercially available Greek yoghurt made from bovine or ovine milk: A comparative study. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 58, 46–49.

- Murakami, M.; Tonouchi, H.; Takahashi, R.; Kitazawa, H.; Kawai, Y.; Negishi, H.; Saito, T. Structural analysis of a new anti-hypertensive peptide (beta-lactosin B) isolated from a commercial whey product. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1967–1974.

- Park, Y.W. Overview of Bioactive Components in Milk and Dairy Products. In Bioactive Components in Milk and Dairy Products; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 3–12.

- Geerlings, A.; Villar, I.; Zarco, F.H.; Sánchez, M.; Vera, R.; Gomez, A.Z.; Boza, J.; Duarte, J. Identification and characterization of novel angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors obtained from goat milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3326–3335.

- Silva, S.V.; Pihlanto, A.; Malcata, F.X. Bioactive peptides in ovine and caprine cheeselike systems prepared with proteases from Cynara cardunculus. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3336–3344.

- Morgan, T.; Nowson, C.; Snowden, R.; Teow, B.H.; Hadji, E.; Hodgson, M.; Anderson, A.; Wilson, D.; Adam, W. The effect of sodium potassium, calcium and magnesium on blood pressure. Recent Adv. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 2, 94.

- Houston, M.C.; Harper, K.J. Potassium, magnesium, and calcium: Their role in both the cause and treatment of hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2008, 10, 3–11.

- Pietrzak-Fiecko, R.; Kamelska-Sadowska, A.M. The Comparison of Nutritional Value of Human Milk with other Mammals’ Milk. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Moya, T.; Planes-Munoz, D.; Frontela-Saseta, C.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Lopez-Nicolas, R. Milk whey from different animal species stimulates the in vitro release of CCK and GLP-1 through a whole simulated intestinal digestion. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7208–7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.P.G.; Van Nieuwenhove, C.; Chaila, Z.; Bazan, C.; Gonzalez, S. Effects of short-term mild calorie restriction diet and renutrition with ruminant milks on leptin levels and other metabolic parameters in mice. Nutrition 2009, 25, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Martin, E.; Garcia-Escobar, E.; Ruiz de Adana, M.S.; Lima-Rubio, F.; Pelaez, L.; Caracuel, A.M.; Bermudez-Silva, F.J.; Soriguer, F.; Rojo-Martinez, G.; Olveira, G. Comparison of the Effects of Goat Dairy and Cow Dairy Based Breakfasts on Satiety, Appetite Hormones, and Metabolic Profile. Nutrients 2017, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, A.M.; Hodgkinson, A.J.; Mitchell, S.M.; Prodhan, U.K.; Prosser, C.G.; Carpenter, E.A.; Fraser, K.; Cameron-Smith, D. Digestive Responses to Fortified Cow or Goat Dairy Drinks: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, A.M.; Samuelsson, L.M.; Shrestha, A.; Sharma, P.; Day, L.; Cameron-Smith, D. Circulating Branched Chain Amino Acid Concentrations Are Higher in Dairy-Avoiding Females following an Equal Volume of Sheep Milk Relative to Cow Milk: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 553674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]