Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Aristolochic acids are known for nephrotoxicity, and implicated in multiple cancer types such as hepatocellular carcinomas.

- aristolochic acid analogues

- biological sources

- natural products

- virtual screening

1. Introduction

Human beings have a long history of taking herbaceous plants as medicines, and there is no doubt that the natural compounds derived from these biological sources are the treasure of potential drug candidates [1][2][3]. Nevertheless, no one can afford to neglect the dark side of an herbal medicine. Take the genus Aristolochia, for instance: Species of Aristolochia have been used for centuries as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in Asian countries and as herbal medicines in many other parts of the world [4]. But until the early 1990s, a weight loss treatment with Aristolochia fangchi (TCM name: Guang Fang Ji) at a Belgian clinic caused kidney failure, and then the medical event drew the attention of people for this toxic herbal medicine [5][6][7]. Epidemiological studies showed that the aristolochic acids (aristolochic acid I and aristolochic acid II) contained in Aristolochia are responsible for a high risk of nephrotoxicity and upper urinary tract carcinoma [8][9][10]. Furthermore, Ng et al. demonstrated that the aristolochic acids and their derivatives are widely implicated in hepatocellular carcinoma [11].

In the mechanism insights into the nephrotoxicity and carcinogenicity of aristolochic acids, a number of metabolites are further metabolized to aristolactams, which can be bio-activated by cytosolic and microsomal enzymes, and cause apoptosis in human proximal tubular cells and porcine renal tubular cells [12][13][14]. On the other hand, aristolochic acids-derived DNA adducts showed distinctive mutational signature, and cased the mutations in known cancer driver genes [11][15][16][17]. Aristolochic acid may be one of the strongest known mutagenic natural products on the human genome, comparing with mutation rates of smoking-associated lung cancer and UV radiation-associated melanoma [16][18][19]. Therefore, definite genotoxic and mutagenic mechanisms are involved in the medicinal plants that contain aristolochic acids.

In view of the above-mentioned toxicity showed by aristolochic acids and their derivatives, characteristics of molecular structure, which, similar to aristolochic acids, should be taken into account for reported nephrotoxicity and carcinogenicity, and the additional chemical space of the natural compounds, are classified as Aristolochic Acid Analogues (AAAs). The known AAAs primarily exist in the genera Aristolochia and Asarum [20][21], and, recently, more undocumented AAAs have been isolated from natural sources [22][23][24]. The suspected toxicity of biological products that contain AAAs deserves further investigation to reassure consumers that these products are safe, as discussed in a recent research by Ang P et al. [25]. However, there is no specific ban of medicinal and edible herbs containing AAAs in certain countries, especially those that are not included in Aristolochiaceae family and easily accessible; for example, the plant Houttuynia cordata (Chinese common name: Yu Xing Cao or Zhe Er Gen) is still widely used in China as potherb and even raw material of TCM injections [26][27]. Therefore, it was suppose that there are more toxic natural products that should be classified as AAAs beyond the existing studies, and the AAAs widely exist in some species which have not attracted considerable attention. A computational approach was described of delving deeper into AAAs, seeking out sufficient naturally occurring AAAs by virtual screening, and clarifying the relationships between AAAs and their biological sources, to find out the implicit chemical space of undocumented AAAs and the wide coverage of organisms that contain AAAs.

The approach of structure-based virtual screening is applicable for the computational task of searching and discovering exceptional molecules in a chemical database [28][29], and the targets of virtual screening implemented could be naturally occurring AAAs. In the theoretical base of the used virtual screening, the conception is finding out the specific features of reported natural molecules that are categorized as AAAs, to determine which chemical structure is an analogue to aristolochic acids. In Structure Activity Relationship (SAR) or Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies, Molecular Similarity (MS) has been used to measure the similarity between molecular structures [30][31]. Calculations of MS based on substructures may be more suitable than those based on molecular descriptors; in consideration of these concepts, some studies compare the scaffold of different compounds to determine the MS values and propose the similarity of biological activity by eliminating R-substituents [32][33][34]. Scaffold structure-based methods show better performance in obtaining structures with the same biological activity and finding out similar compounds among different families during the screening process [35]. Thus, the Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) of reported aristolochic acids can make the representation of the main features of AAAs.

2. Chemical Space of Naturally Occurring Aristolochic Acid Analogues

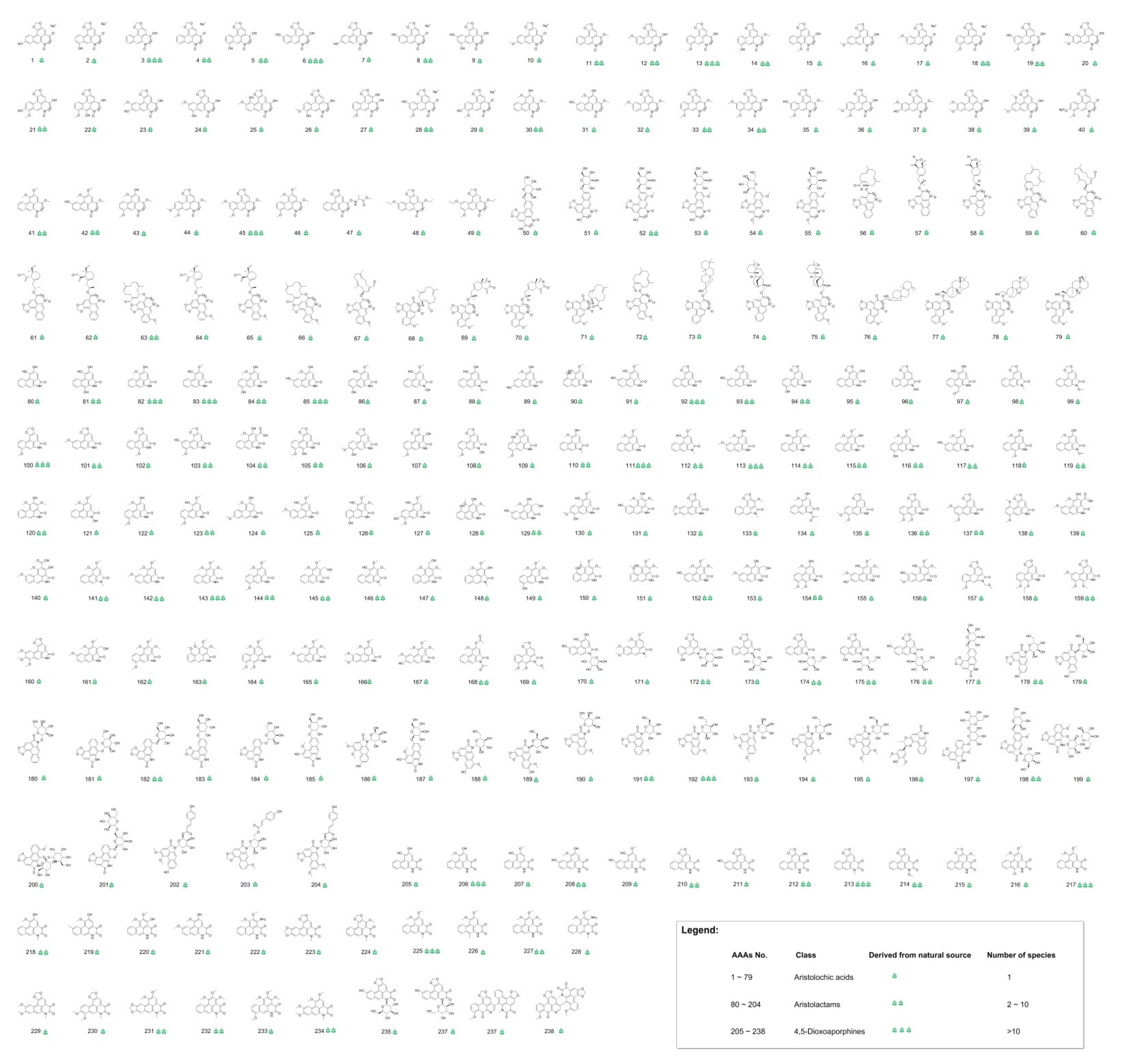

Comprehensive classification of AAAs is based on molecular structural features of reported AAAs, and three categories of AAAs are classified as aristolochic acids, aristolactams and 4,5-dioxoaporphines. The used approach of virtual screening resulted in 238 naturally occurring AAAs (the serial number of aristolochic acid analogues listed under each structure is defined as “AAAs No.”), including 79 aristolochic acids (AAAs No. 1–79), 125 aristolactams (AAAs No. 80–204) and 34 4,5-dioxoaporphines (AAAs No. 205–238). The AAAs are all reported as natural products and having specific species of biological sources; 80 AAAs are present in more than 2 species, and 17 AAAs are present in more than 10 species, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The result of naturally occurring aristolochic acid analogues obtained by virtual screening.

As observed from computed molecular properties data, the molecules of AAAs consist of at least 3 and up to 15 oxygen atoms and at least 1 nitrogen atom and have an average molecular weight value of 381.24. The Calculated LogP (CLogP) and Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) values of AAAs scatter in the range of −2.33–7.96 and 38.77–237.53, as showed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The scatter plot of molecular properties of aristolochic acid analogues.

3. Coverage of Biological Sources Containing Aristolochic Acid Analogues

A total of 175 species of biological sources are revealed to contain AAAs. The biological sources include not only species of Aristolochiaceae but various plants in 13 families of the class Magnoliopsida (Figure 3). The biological sources are reported to contain at least 1 AAAs, 22 of them containing more than 10 AAAs, and the species of Aristolochia kaempferi is reported to contain the maximum number of AAAs. Aristolochic acid I (AAAs No. 13) and aristolochic acid II (AAAs No. 3), which are considered to be the main constituents responsible for the nephrotoxic and carcinogenic effects, are present in 52 species; it is particularly remarkable that these two compounds are widespread in the species of Aristolochiaceae and Ranunculaceae. According to the investigation, 44 species of the biological sources have been used as TCM, including Aristolochia kaempferi (TCM name: Han Zhong Fang Ji), Aristolochia contorta (TCM name: Ma Dou Pu), Aristolochia manshuriensis (TCM name: Guan Mu Tong), and Aristolochia mollissima (TCM name: Xun Gu Feng), which not only contain more than 20 AAAs, but also are reported to contain both aristolochic acid I and aristolochic acid II.

Figure 3. The taxonomic distribution of species containing aristolochic acid analogues.

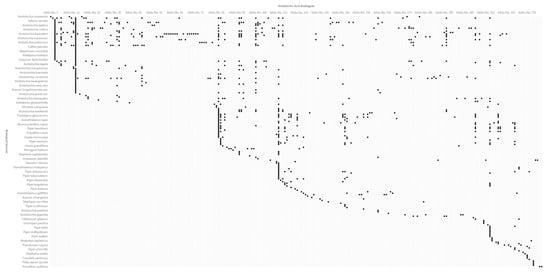

4. Relationship of Aristolochic Acid Analogues and Their Biological Sources

In the relationship matrix analysis (Figure 4) of AAAs and their biological sources, it was found that the same AAAs can originate from various species, which may be irrelevant in biological taxonomy, and the three categories of AAAs (aristolochic acids, aristolactams and 4,5-dioxoaporphines) may coexist in a specific species of biological sources. The genus Aristolochia covers the most diverse of AAAs, which may be a significant factor of toxicity of the plants belonging to this genus. The table of relational data between AAAs and their biological sources was achieved in order to see which species of biological source contain a specific AAAs based on column “AAAs No.” and the table of AAAs data, for example, the analysis of species containing aristolochic acid I (AAAs No. 13). Similarly, AAAs that are present in a specific species can be found based on column “Biological Sources” and the table of biological source data, for example, the analysis of AAAs that are present in the species of Aristolochia kaempferi or the TCM “Han Zhong Fang Ji”. Moreover, all of the 781 records of relational data are accompanied with references, from which the AAAs were reported.

Figure 4. Relationship matrix analysis of aristolochic acid analogues and their biological sources.

5. Conclusions

In silico toxicology estimation is not intended as a substitute for appropriate animal or clinical studies, and computer-predicted toxicity data of AAAs are not enough to determine the potential hazard of their biological sources. However, with the panorama of AAAs and their biological sources, there will be a toxicological profile of species containing AAAs. In view of the fact that the biological sources involve a considerable number of TCMs that can be easily available by online purchases, the result data may act as warnings to herbal medicine abuse.

Abbreviations

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| AAAs | Aristolochic Acid Analogues |

| SAR | Structure Activity Relationship |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship |

| MS | Molecular Similarity |

| MCS | Maximum Common Substructure |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom11091344

References

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216.

- Butler, M.S. The Role of Natural Product Chemistry in Drug Discovery. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 2141–2153.

- The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1217–1220.

- Heinrich, M.; Chan, J.; Wanke, S.; Neinhuis, C.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Local uses of Aristolochia species and content of nephrotoxic aristolochic acid 1 and 2—A global assessment based on bibliographic sources. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 108–144.

- Vanherweghem, J.L. A new form of nephropathy secondary to the absorption of Chinese herbs. Bull. Mem. Acad. R. Med. Belg. 1994, 149, 128–135.

- Vanherweghem, J.L. Misuse of herbal remedies: The case of an outbreak of terminal renal failure in Belgium (Chinese herbs nephropathy). J. Altern. Complement. Med. 1998, 4, 9–13.

- Debelle, F.D.; Vanherweghem, J.L.; Nortier, J.L. Aristolochic acid nephropathy: A worldwide problem. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 158–169.

- De Broe, M.E. On a nephrotoxic and carcinogenic slimming regimen. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1999, 33, 1171–1173.

- Grollman, A.P.; Shibutani, S.; Moriya, M.; Miller, F.; Wu, L.; Moll, U.; Jelakovic, B. Aristolochic acid and the etiology of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12129–12134.

- Nortier, J.L.; Martinez, M.-C.M.; Schmeiser, H.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Bieler, C.A.; Petein, M.; Vanherweghem, J.-L. Urothelial Carcinoma Associated with the Use of a Chinese Herb (Aristolochia fangchi). N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1686–1692.

- Ng, A.W.T.; Poon, S.L.; Huang, M.N.; Lim, J.Q.; Boot, A.; Yu, W.; Rozen, S.G. Aristolochic acids and their derivatives are widely implicated in liver cancers in Taiwan and throughout Asia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaan6446.

- Stiborová, M.; Frei, E.; Arlt, V.M.; Schmeiser, H.H. Metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid, a risk factor for Balkan endemic nephropathy. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2008, 658, 55–67.

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Shu, B.; Li, F.; Bao, Q.; Zhang, L. Toxicities of aristolochic acid I and aristololactam I in cultured renal epithelial cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010, 24, 1092–1097.

- Balachandran, P.; Wei, F.; Lin, R.-C.; Khan, I.A.; Pasco, D.S. Structure activity relationships of aristolochic acid analogues: Toxicity in cultured renal epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 1797–1805.

- Hoang, M.L.; Chen, C.-H.; Sidorenko, V.S.; He, J.; Dickman, K.G.; Yun, B.H.; Rosenquist, T.A. Mutational Signature of Aristolochic Acid Exposure as Revealed by Whole-Exome Sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 197ra102.

- Poon, S.L.; Pang, S.-T.; McPherson, J.R.; Yu, W.; Huang, K.K.; Guan, P.; Teh, B.T. Genome-Wide Mutational Signatures of Aristolochic Acid and Its Application as a Screening Tool. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 197ra101.

- Chen, C.-H.; Dickman, K.G.; Moriya, M.; Zavadil, J.; Sidorenko, V.S.; Edwards, K.L.; Grollman, A.P. Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8241–8246.

- Imielinski, M.; Berger, A.H.; Hammerman, P.S.; Hernandez, B.; Pugh, T.J.; Hodis, E.; Meyerson, M. Mapping the Hallmarks of Lung Adenocarcinoma with Massively Parallel Sequencing. Cell 2012, 150, 1107–1120.

- Berger, M.F.; Hodis, E.; Heffernan, T.P.; Deribe, Y.L.; Lawrence, M.S.; Protopopov, A.; Garraway, L.A. Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. Nature 2012, 485, 502–506.

- Kumar, V.; Poonam; Prasad, A.K.; Parmar, V.S. Naturally occurring aristolactams, aristolochic acids and dioxoaporphines and their biological activities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003, 20, 565.

- Michl, J.; Ingrouille, M.J.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Heinrich, M. Naturally occurring aristolochic acid analogues and their toxicities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 676–693.

- Ji, H.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; Wu, W.; Yao, C.; Yao, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, D. Two New Aristolochic Acid Analogues from the Roots of Aristolochia contorta with Significant Cytotoxic Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 44.

- Ma, H.; Dong, C.; Zhou, X.; Bu, M.; Yu, S. Aristololactam derivatives from the fruits of Aristolochia contorta Bunge. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2505–2509.

- Ma, Q.; Wei, R.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Sang, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, H. Bioactive alkaloids from the aerial parts of Houttuynia cordata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 195, 166–172.

- Ang, L.P.; Ng, P.W.; Lean, Y.L.; Kotra, V.; Kifli, N.; Goh, H.P.; Lee, K.S.; Sarker, M.M.R.; Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Ming, L.C. Herbal products containing aristolochic acids: A call to revisit the context of safety. J. Herb. Med. 2021, 28, 100447.

- Wang, L.; Cui, X.; Cheng, L.; Yuan, Q.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Deng, S.; Shang, H.; Bian, Z. Adverse events to Houttuynia injection: A systematic review. J. Evid.-Based. Med. 2010, 3, 168–176.

- Cheung, T.P.; Xue, C.; Leung, K.; Chan, K.; Li, C.G. Aristolochic Acids Detected in Some Raw Chinese Medicinal Herbs and Manufactured Herbal Products—A Consequence of Inappropriate Nomenclature and Imprecise Labelling? Clin. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 371–378.

- Santibáñez-Morán, M.G.; López-López, E.; Prieto-Martínez, F.D.; Sánchez-Cruz, N.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Consensus virtual screening of dark chemical matter and food chemicals uncover potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 25089–25099.

- Xu, T.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Dai, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Virtual Screening for Reactive Natural Products and Their Probable Artifacts of Solvolysis and Oxidation. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1486.

- Maggiora, G.; Vogt, M.; Stumpfe, D.; Bajorath, J. Molecular similarity in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 57, 3186–3204.

- Riniker, S.; Landrum, G.A. Similarity Maps—A Visualization Strategy for Molecular Fingerprints and Machine-Learning Methods. J. Cheminf. 2013, 5, 43.

- Vogt, M.; Stumpfe, D.; Geppert, H.; Bajorath, J. Scaffold hopping using two-dimensional fingerprints: True potential, black magic, or a hopeless endeavor? guidelines for virtual screening. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 12, 5707–5715.

- Hu, Y.; Stumpfe, D.; Bajorath, J. Recent advances in scaffold hopping. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1238–1246.

- Kunimoto, R.; Vogt, M.; Bajorath, J. Maximum common substructure-based Tversky index: An asymmetric hybrid similarity measure. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 523–531.

- Antelo-Collado, A.; Carrasco-Velar, R.; García-Pedrajas, N.; Cerruela-García, G. Maximum common property: A new approach for molecular similarity. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 61.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!