Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Area Studies

Alien species are among the five drivers of environmental change with the largest relative global impacts. In particular, horticulture is a major introduction pathway of alien plants, but, together with intentional introductions, plants can also be introduced and spread via human-mediated involuntary pathways as contaminants and stowaways.

- invasive alien species

- pathways

- Regulation EU 1143/2014

- agriculture

1. Introduction

Invasive alien species are among the five drivers of environmental change with the largest relative global impacts [1]. Recently, Pyšek et al. [2] reviewed negative impacts that severely affect invaded areas, warning that they are accelerating and will further increase in the future: invasive alien species break down biogeographic realms, affect native species richness and abundance, also increasing their risk of extinction, influence the genetic composition of native populations, change native animal behaviour, alter phylogenetic diversity across communities, and modify trophic networks. Many invasive alien species also change ecosystem functioning and the delivery of ecosystem services by altering nutrient and contaminant cycling, hydrology, habitat structure, and disturbance regimes. Human health and economy can also be deeply altered by invasive alien species. Intrinsically, an alien species is a taxon of which the presence in a region is attributable to human transport, whether deliberate or accidental, which has enabled it to overcome otherwise impassable biogeographical barriers of its native geographic distribution [3][4]. Consequently, biological invasions and their accelerating rate are a global consequence of an increasingly connected world and the increase in human population size [2][5][6] .

In total, 13,168 plant species, corresponding to 3.9% of the extant global vascular flora, have become naturalized alien species somewhere else on the globe as a result of human activity [7]. As a result of the increasing rate of biological invasion, the contribution of specific introduction pathways and their changes over time are receiving increasing attention from scientists and policymakers [8]. Intentional introductions by man in new ranges have been fundamental to alien plant spread and naturalization at global level [9]. Humans have cultivated alien plants from the Late Pleistocene onwards, but the introduction of alien plants of economic value drastically increased since the 15th century, when Europeans started exploring the world [10]; today, biological invasions are synonymous with international trade [6]. Generally, economic plants (ornamental, fodder, food, medicinal plants, etc.) experienced major success and often became naturalized as they had more opportunities for introduction and spread than most non-cultivated species, because they are actively propagated and repeatedly planted in large numbers over large areas [10]. In particular, horticulture is a major introduction pathway of alien plants [11].

However, together with intentional introductions, plants can also be introduced and spread via involuntary human-mediated pathways. This is the case of plants or their propagules accidentally being transported as contaminants and/or stowaways. Plants are not among the organisms that are most frequently associated with these unintentional pathways (e.g., insects); however, the risk of their introduction and spread through contaminated commodities or as hitchhikers on means of transport has been recorded (today and in the past) and cannot be overlooked [12][13]. Seeds, spores, fragments of plants, sister clones, or plantlets are both viable propagules and resistance units suitable to be accidentally transported through various vectors along pathways, both for short and long distances. Recurring accidental introduction of alien plants to new areas can be the prelude to an invasion on a large scale; this has been the case, for example, of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L., which was likely introduced as contaminant of grain commodities from North America to Europe and elsewhere, and today it is a widespread invasive alien plant with highly detrimental effects on human health and agriculture [14]).

As a historic epicentre of migration, tourism, trade, and agriculture, Europe represents a hub for alien species introduction [15]. Beyond phytosanitary measures (Regulation (EU) no. 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants), since 2015, Regulation (EU) no. 1143/2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species came into force in the European Union (EU) to manage biological invasions and mitigate their impacts [16]. Built on the statement that “prevention is better than cure”, the regulation introduces some renown IAS management pillars into the legislation corpus, such as the promotion of early-warning and surveillance systems, rapid eradications to prevent establishment and long-term mitigation, as well as control mechanisms; in addition, it recognizes the key role of both deliberate and accidental introductions of invasive alien species and requires Member States to develop tailored action plans to address priority pathways [17]. All efforts are addressed to manage a list of priority species, classed as invasive alien species of Union concern. Following this preventive approach, the list includes organisms, both occurring and absent, but that are likely to be introduced into the EU. All invasive alien species of Union concern have severe real or potential detrimental effects on biodiversity, economy, and health in the European Union, as well as in other continents. According to the regulation, the adoption of a ban at the Union level on intentionally or negligently bringing into the Union these species is essential. Restrictions on reproducing, growing, transporting, buying, selling, using, exchanging, keeping, and releasing invasive alien species of Union concern are key in the strategy of regulation. Focusing in particular on invasive alien plants of Union concern (IAPUC), as these species have been introduced and have spread mainly as ornamental plants for a long time, restrictions have mostly translated to trade and possession bans. However, for almost all IAPUC, an accidental pathways can be identified, which should be managed in order to prevent proliferation, and a small percentage of these are taxa of which introduction and spread is mainly related to unintentional human-mediated vectors (or not clearly understood pathways). Nonetheless phytosanitary measures and efforts applied at the EU level, criticisms in inspections, and implementation of biosecurity protocols remain, and risks to keep involuntary pathways active are not remote [6]. Agriculture, in its widest meaning (including horticulture and sub-sectors as livestock, agro-forestry, and aquaculture), represents a sector that is severely impacted by invasive alien species [18] and, at the same time, is likely to be one of the main factors responsible of biological invasions [13].

2. Accidental Introduction and Secondary Spread in Agriculture-Related Activities: Contaminants’ and Stowaways’ Pathways

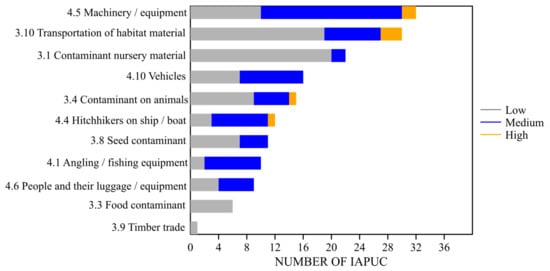

The most frequently cited agricultural pathways of accidental transportation for IAPUC are listed in Figure 1 gives a simplified overview.

Figure 1. IAPUC introduced and spread as contaminants and/or stowaway in agriculture: representativeness of unintentional pathways of introduction and spread and their likelihood (grey = low, blue = medium, orange = high).

Sub-category “4.5 Machinery/equipment” resulted to be the most frequent pathway of accidental transportation of IAPUC as stowaway, followed by the contamination of habitat material (“3.10 Transportation of habitat material (soil, vegetation, wood…)”). Both are quite general pathways (not requiring specific plant adaptations or conditions) that are easy to detect or infer, as are those involving the transport on vehicles (“4.10 Vehicles (car, train, etc.)”) and vessels (“4.4 Hitchhikers on ship/boat (excluding ballast water and hull fouling”), which is particularly relevant for aquatic IAPUC. The role of machinery and equipment was already found to be important for plants by Pergl et al. [13], especially for their secondary spread rather than their primary introduction in the EU, and the same can be said for pathway related to the transportation of habitat material and contamination of nursery plans. On the contrary, pathways related to the contamination of seeds, foods, and animals were less frequently cited for IAPUC, while, for Pergl et al. [13], at least seed contamination had a main role in the introduction and spread of alien plants. Such discrepancies are likely related to the different samples of the analysed species with respect to the broad group of alien plants analysed by Pergl et al. [13]. A few IAPUC are crop weeds, a category which usually includes species that most likely become “contaminants”.

The likelihood of IAPUC being introduced or spread through a new range through one of the considered accidental pathways is generally not very high (Figure 1). In particular, this is true for their introduction to a new area, as, for the most part, voluntary IAPUC introduction pathways are more likely (e.g., ornamental plant trade). With respect to the introduction stage, accidental pathways are more likely to act in the spread of IAPUC; however, the likelihood is meanly low or moderate. In few cases there is a high chance that species could be spread via accidental pathways, but it can happen in the case of transportation and spread via habitat materials (mostly soil) (e.g., Acacia saligna, Ailanthus altissima), machinery and equipment (e.g., Pennisetum setaceum), and marginally through animals (e.g., livestock), as seed contaminant and hitchhiker on vessels. More often, pathways related to transportation of habitat material and presence as hitchhikers on machinery and equipment, vehicles and other means of transportation are moderately likely. However, even if the likelihood is not always high, attention on agriculture-related pathways should be maintained. Insights about involuntary pathways are given in following sections.

2.1. Stowaways: Machinery, Equipment, Vehicles and Vessels

The main routes that could lead to the introduction and spread of IAPUC as stowaways are “4.5 Machinery/equipment”, followed by “4.10 Vehicles (car, train, etc.)” and “4.4 Hitchhikers on ship/boat (excluding ballast water and hull fouling)”, which is of key importance for macrophytes; minor pathways for IAPUC are “4.1 Angling/fishing equipment” and “4.6 People and their luggage/equipment (in particular tourism)” (Figure 1).

In agriculture, machinery and equipment can refer to a broad selection of items eligible to work as stowaway vectors, both on land and on inland waters. Firstly, this category can include both machinery and powered (e.g., trimmers) or hand tools (e.g., hoes, rakes, spades). Devices can be specific for agriculture or employable also for other activities, such as loaders, excavators on land or weed cutting buckets, dredges in inland waters can also be used, for example, in construction sites, channels cleaning, etc. All these vectors have in common that viable plant propagules can be accidentally transported directly, nested in the machine body or implements (e.g., embedded in cracks, crevices, and components) or with the litter, soil, or mud attached to external or internal parts of the machines and devices (e.g., tire treads, tracks). Because of their structure and size, large-sized machinery is more viable to be an efficient stowaway vector than small-sized powered or hand tools, of which the dimensions and body structure are generally not highly suitable for the attachment of high amounts of viable propagules; despite this, their role as stowaway vectors should not be neglected.

This pathway has clear affinities with another important pathway for IAPUC, “4.10 Vehicles (car, train, etc.)” (Figure 1), which is related to the accidental introduction and spread of IAPUC via means of transportation (cars, vans, lorries, trucks, trains) [19]. Even if not exclusively related to agriculture, vehicles for transportation are commonly used in farming and forestry contexts; furthermore, in the patchwork of cultivated lands that characterize wide regions of the EU, agricultural areas are often crossed by linear infrastructure (from highways to rural or forest roads), with a consequent potential of remarkable propagule pressure from this kind of pathway. The mechanism of transportation of IAPUC as hitchhikers on vehicles is the same as in the “machinery/equipment” pathways (physical attachment to the body or components of the vehicle); seeds can be accumulated differently in different parts of vehicles [20]. Vehicles can accrue a wide variety of seeds and plant propagules, and driving surface, road conditions, and seasons affect the rate of accrual. The type of vehicle also has relevance; for example, it has been observed that, on unpaved roads (where the risk of gaining propagules is likely to be higher than on paved roads), tracked vehicles accrue more seeds than small and large 4-wheel-drive vehicles and that the rates of accrual dramatically increase under wet conditions, which make surfaces muddy [21]. These considerations can also be extended to the machinery pathway, whose contribution to propagules dispersal can be affected by machinery types, as well as soil conditions [22][23].

It is very important to underline that the risk of transporting viable plant propagules via vehicles, machinery, and equipment (VME) is strictly related to previous “in field” use in invaded sites, condition that would allow the attachment of viable propagules of plants to vehicles, machines, and tools. Consequently, the second-hand VME trade has a predominant role with respect to brand-new articles on the market in introducing and spreading IAPUC [24]. This pathway has relevance both at small and large scales. Locally, VME can be routinely used at different sites, following operational relocations, with a consequent spread or introduction of propagules in different places at a small scale; Ansong and Pickering [20] found that seeds can be dispersed over hundreds of kilometres by cars, even if they usually fall off after shorter distances. At a wider scale, the second-hand VME trade can work as vectors of introduction at the international level thanks to the resistance of viable plant propagules.

In France, the spread of Andropogon virginicus has been assumed to be related to the movement of forest machinery in pinewoods management [25]. Lygodium japonicum is a climbing fern that is likely to be transported as a stowaway via VME with certain ease. Rhizomes and roots fragments may remain viable for several days if embedded in soil within machinery or equipment, which protects them from desiccation [26], but spores are viable for longer (up to 5 years), and are likely to be found on the surfaces and crevices of VME, as well as on quite small powered and hand tools. A thorough analysis by Hutchinson and Langeland [27] revealed the presence of spores (also attached to fern micro-fragments) and gametophytes of L. microphyllum, especially on chainsaws, sprayers, and machetes, used in controlling exotic ferns in the USA; operators themselves resulted in being active pathways of transportation of viable propagules (Figure 1). This is also expected to happen with spores of L. japonicum, due to the similarities in life history, reproductive biology, habitus and living environments between these two congener ferns [28]. Other successful cases of transportation through VME can be associated with many other plants. For example, seeds of Impatiens glandulifera Royle, a very prolific annual plant, can be successfully transported as hitchhikers on agricultural machinery (e.g., mowers, tractor wheels) [29], as well as those of Asclepias syriaca L. that are not dispersed by wind [30]; seeds and fragments of plants of Pueraria montana can be accidentally introduced or spread via VME, both in agricultural and other contexts, including snow removal activities [31][32]. Information about the likelihood of being transported as stowaways on VME can come from different sources, and are linked both to scientific investigations and anecdotal and case-specific observations. Furthermore, evidence can also come from data gathered in sectors other than agriculture and forestry, representing valid information as the mechanisms and vectors types are comparable to those employed in farming and silviculture. An exemplificative case is represented by Microstegium vimineum, of which transportation and spread as a stowaway on machinery and vehicles has been investigated during routine rural road maintenance along a forest road in the USA [22].

Additionally, vehicles may promote the spread of viable propagules of invasive alien plants thanks to the airflow created by their passage [32]. This mechanism of human-mediated dispersal is usually relevant, especially for species producing seeds adapted to anemochory (winged or plumed seeds/fruit). For example, samaras of A. altissima can be transported for more than 150 m in the slipstream of vehicles along highways [33]; dried seed-containing pods of Acacia saligna (as other Fabaceae) have the potential to be moved by vehicle passage and by wind [34][35][36]. The potential of being moved by airflow should not be disregarded for other species producing seeds that are not specialized to anemochorous dispersal, but that can be wind-dispersed, even if more slowly and for smaller distances, as demonstrated for the non-IAPUC Brassica napus (round and smooth seeds) and Ambrosia artemisiifolia (hooked cypselae) according to von der Lippe [32].

In freshwater environments, seeds, but more than often fragments of macrophytes, with highly regenerative capacity and resistance to desiccation, can be successfully transported as hitchhikers to new sites on VME [37]. Obviously, together with VME, the transport of hitchhikers on vessels is a highly relevant pathway for aquatic or amphibious IAPUC (“4.4 Hitchhikers on ship/boat (excluding ballast water and hull fouling)”); in fact, for all of them, this is a potential pathway (Figure 1). Pathways related to VME and vessels can operate both in aquatic and terrestrial (riparian) environments; transportation can occur entirely along watercourses (natural and artificial) or banks, but it can also include overland routes as well, both at local and international scales (e.g., international trade, second-hand market). Among aquatic IAPUC, Elodea nuttallii, Lagarosiphon major, and also Myriophyllum aquaticum, can be accidentally transported on vessels, boat trailers, and aquatic weed machinery, which can be moved from site to site along the same watercourse or changing water systems if transported to sites that are not interconnected. It is likely that the helophyte Gymnocoronis spilanthoides takes advantage of hitchhiking on cleaning machines, which seasonally mow the vegetation along channels in rice fields in Italy [38]. For amphibious IAPUC living on the shores of waterbodies, such as Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb. or Ludwigia sp.pl., the contribution of terrestrial VME accessing banks should not be overlooked in their accidental transportation to new sites.

Obviously not all IAPUC have the same likelihood to be transported thanks to VME and vessels. These pathways are not considered highly likely for all IAPUC where it is considered possible. For example, the EPPO [39] indicated that the transportation of viable propagules of Lysichiton americanus (Hultén and St. John) (pieces of rhizome) through machinery and vehicles is a remote possibility due to depth of the rhizomes of the plant, and the few management measures in the habitats where it occurs (wet or waterlogged forests). Another case regards seed-containing pods and seeds of Prosopis juliflora that are not considered highly prone to adhere to machinery and vehicles by experts [40]. Among macrophytes, for Eichhornia crassipes, it is less likely to be transported as hitchhikers on machinery and boats than other macrophytes, due to the conspicuous nature of its propagules (which usually are not small, undetectable ramets) [41].

2.2. Stowaways: Minor Pathways

Secondary to pathways involving VME and vessels, “4.1 Angling/fishing equipment” and “4.6 People and their luggage/equipment (in particular tourism)” are other potential routes of accidental introduction and spread for IAPUC (Figure 1). Angling/fishing equipment is a relevant pathway for most aquatic IAPUC, while transportation thanks to attachment to clothes, footwear, and personal equipment is less frequent. Both pathways can be effective at local and international scales. Beyond the potential trade of unclean equipment, there is also the risk of directly introducing contaminated items previously used in sites abroad; for example, analysing British anglers’ movements in Europe, Smith et al. [42] found frequent fishing trips abroad, often on distances covered within the time frame that alien invasive species have been shown to survive on damp angling equipment (e.g., from Great Britain to Western Europe and vice versa), with a consequent potential impact on the entry of propagules into new areas from other countries. Analysing the pathway “People and their luggage/equipment (in particular tourism)” is relevant to provide the magnitude of risk of introducing and spreading IAPUC through human-vectored seed dispersal in other words on clothes, footwear, personal equipment, as an alternative form of epizoochory on mammals’ fur or hooves [43]. Factors that affect this pathway include several variables, such as the type of clothing and fabric, their position on plants, seeds morphology and seed traits, such as adhesive and attachment structures [20]. This pathway is usually especially relevant for Poaceae [43][20], as also happens for IAPUC; secondary to Poaceae, Apiaceae with Heracleum spp. could be transported attached to clothes [44]. There are no specific studies focused on human-vectored seed dispersal in agriculture and forestry, but it is expected to be as relevant as other categories, such as runners and hikers [45], keeping in mind that the amount of seeds likely to be transported by soil attached to footwear can be remarkable (3 seeds per gram of soil) [46].

2.3. Contaminants: Habitat and Nursery Material

The category “3.10 Transportation of habitat material (soil, vegetation, wood, etc.)” is one of the most frequently cited pathways of introduction and spread for IAPUC (Figure 1). Specifically, for this pathway, the main role is played by the transport of soils contaminated with viable propagules of plants. and only in few cases does the contamination regard different materials (e.g., hay). Soil has already been cited as a media facilitating the accrual of propagules on VME, or it can represent the mean of contamination in nursery plants (“3.1 Contaminant nursery material”). In this case, soil has to be considered a commodity itself, which is traded and/or transported as growing media (not a relatively small amount associated with plants) [19], waste, and also for restoration activities (e.g., backfilling material in quarry restoration) [47]. It can be a relevant pathway, especially for terrestrial and amphibious IAPUC, while it is usually not cited for aquatic species, even if it cannot be excluded that short-distance transport of wet soil (ensuring the right conditions to maintain propagules viable against desiccation) could actively contribute to spread. Viable propagules eligible to be transported as soil contaminants are seeds or spores and fragments of plants with regenerative capacity (mostly fragments of rhizomes and roots). Regarding seeds, their viability and quantity/density in soil are determinant variables for successful dispersal along this pathway. All IAPUC likely to be accidentally transported in soil can produce quite long-lasting soil seed banks with seed viability generally spanning from a few years to decades. In addition to a persistent soil seed bank, prolific viable seed production is another trait usually common to these IAPUC. For Acacia saligna seeds, density in soil is variable, but can exceed 15,000 seeds m−2 [48][49] and a density of 10,000–100,000 seedlings m−2 has been found for Gunnera tinctoria [50]. Seeds of A. saligna have a funicle and aril (elaiosome) and are suited to myrmecochorous dispersal; ants can also contribute to their accumulation in the first soil layer [48]. The soil seed bank of Impatiens glandulifera can reach exceptionally high densities (32,000 seeds m−2) and even if most seeds germinate during the spring following their dispersal, according tothe annual plant strategy, a small part of these can maintain viability for 4 years [51][52]. I. glandulifera frequently colonizes riparian habitats, so its seeds can be mostly found in riverine top soil and gravel, which\ can be vectors of transport, even if they are moved in small amounts due to the high density of seeds [29][52].

Together with seeds, highly-regenerative fragments of IAPUC can be transported, embedded in soils, ready to sprout when solicited. Beyond prolific seed production, the key of success of Asclepias syriaca is in its rhizome, thanks to its below-ground modified stem, is due to the plants forming a viable “bud bank” in soil and, in case of disturbance (e.g., soil excavation), fragmentation of the rhizome produces viable units able to generate new plants (clones), thanks to sprouting from buds [30]. Another interesting case is the highly invasive Ailanthus altissima. In addition to an amazing production of seeds, this IAPUC can also be effectively transported with soils thanks to its highly regenerative dispersal units; fragments of stem or root with adventive buds, even small-sized ones (<1 cm), can maintain viability, even after environmental stress (e.g., submersion), generating new clones and boosting the dispersal of the plant [53][54][55].

The movement of contaminated soil can contribute to IAPUC dispersal, both at local and international scales. It is quite easy to figure out how this pathway works at a local scale, thinking about the excavation of soil and its re-use or disposal at other sites during a wide array of agricultural activities. At the international scale, soil trade volume and characteristics are not easy to trace, even at the EU level. It is relevant to notice that within the EU there are no particular restrictions or requirements for the inspection of soils moving from one Member State to another and only a small proportion of soil entering the EU is inspected at points of entry for the transportation of associated harmful organisms, and inspection intensity largely varies between EU Member States [56]. Consequently, the contribution of this pathway can be relevant in introducing and spreading IAPUC from other countries, inside or outside the EU.

Beyond soil, some IAPUC can be accidentally transported with other types of habitat material, even if other vectors seem to be less relevant in the EU. The most frequently cited vector is hay and, among IAPUC, it especially is noteworthy in the context of Poaceae. For Andropogon virginicus, Pennisetum setaceum, Ehrharta calycina, and Microstegium vimineum the accidental introduction through import of contaminated hay has been cited, even if evidence about the real role of this pathways is lacking. For example, even if transport of hay (and livestock) is observed for A. virginicus in Australia (secondary spread), on the other hand, its introduction through contaminated hay from USA to Europe has to be inferred; there is no published evidence of A. virginicus being transported as part of hay material from the USA, while there is evidence that hay is imported into the EU and that seed material of A. virginicus can potentially be included [57]. The same can be said for E. calycina [58]. For M. vimineum, this pathway is simply cited [59] and, for P. setaceum, hay contamination is only supposed to have a role in the primary introduction to Australia [60]. A peculiar case is represented by the fern Lygodium japonicum, of which spores can be contaminants of pine straw. Clear evidence of contamination has been observed in the USA where the fern is invasive in pine plantations related to specific pine straw production; even if pine straw is not imported from the USA to the EU and this has to be considered a minor pathway [26], this information gives a measure of the high dispersal potential of the fern.

The contamination of nursery material is another relevant involuntary pathway of introduction and spread for several IAPUC. Responsible for this contamination are usually seeds, spores, or fragments of contaminant plants that “accidentally colonize” soils or water where terrestrial or aquatic nursery plants are grown. This is possible if contaminant plant propagules occur in the nursery, conditions that today are likely to happen mostly outside of EU borders, where there are no restrictions on trade and the possession of IAPUC. For example, both Alternanthera philoxeroides and L. japonicum have been found to be contaminants in bonsai imported from China [61][62]. Persicaria perfoliata can be a contaminant of nursery plants through growing media (e.g., Rhododendron L. stock, forestry trees) [63]. Among aquatic IAPUC, Hydrocotyle ranunculoides has been found to be a contaminant of cultivated H. vulgaris in Europe, but before entry into force of Regulation 1143/2014 [64]. Due to the scarce detectability of propagules and their large use, aquatic plants, such as Elodea nuttallii and Lagarosiphon major, are often cited as contaminant of other aquarium plants, even if direct observations are missing for both species [65][66]. Especially for IAPUC of which identification can be criticized (e.g., macrophytes), the contamination of nursery plants can be related also to the “accidental” use of mislabeled species [67], especially for species whose congeners are regularly traded (e.g., Cenchrus L. or Pennisetum Rich., Ludwigia L., Myriophyllum L.).

A non-negligible number of IAPUC is likely to be accidentally transported with livestock; species can be attached to fur, with soil to clogs, and they can be found in dung. As already said, seeds of A. virginicus may have been spread in Australia through livestock and possibly through hay used for animals [57]. Seeds of E. calycina are likely to be transported attached to fur, but can also be found in the dung of animals grazing contaminated hay [68]. Livestock eating its pods could also contribute to the spread of Prosopis juliflora, even if this has not been observed in the EU [69]. On the other hand, propagules of Gymnocoronis spilanthoides can be transported attached to animal hooves [70].

2.4. Contaminants: Minor Pathways

IAPUC are not frequently cited as contaminant of seeds or foods (Figure 1), probably because few of them are weeds of crops and are rarely used as plant for food or in food-making processes. Anyway for several IAPUC these pathways can be key in their introduction and spread in new ranges. One of these is Parthenium hysterophorus L., forb devoid of any economic interest, and was primarily introduced as contaminant outside its native range [71]. Seeds of P. hysteorphorus have been found to be contaminants of seeds for planting (cereals, vegetables, field crops, pasture seed, seeds for animal consumption—“3.8 Seed contaminant”) and seeds for human consumption (grains—“3.3 Food contaminant”), especially introduced by shipments coming from the USA [71]. In this case, these pathways are likely to be very effective in the primary introduction of P. hysteorphorus in its invasive range. In fact, in the EU, even if the plant is not yet naturalized but has been recorded as a casual occurrence, P. hysteorphorus has been found, especially near entry points of grains and other seeds or mills [71], supporting the relevance of the introduction of the species as a contaminant of seeds for planting or food and the risk of its establishment. Among IAPUC not yet naturalized in the EU, this species is one of the most worrying as it could be introduced and spread following a wide array of pathways and it would probably find suitable conditions in Europe [72]. Other IAPUC can be contaminant of birdseed (Alternanthera philoxeroides, Microstegium vimineum) or seeds for planting (Persicaria perfoliata has been introduced, most likely with the importation of Ilex sp. seeds to Pennsylvania, USA) [63]. Even if it has to be considered as a pathway of secondary importance, Heracleum mantegazzianum has been found to be a contaminant of seeds of other Apiaceae for food use (Carum carvi L., source of cumin) and its seeds have been transported as spice (golpar), probably due to misidentification [73]. Cortaderia jubata and Myriophyllum aquaticum use different mechanism of contamination: basing on evidences regarding C. selloana (Schult. & Schult.f.) Asch. & Graebn., seeds of C. jubata could be transported as food contaminant due to attachment to the hairy surface of kiwi fruits (Actinidia deliciosa (A. Chev.) C.F. Liang & A.R. Ferguson) [72][74], while fragments of M. aquaticum could be accidentally transported as contaminants of stocked fish [75].

Misidentification of plants or their parts can be also the basis for accidental transportation as food contaminant. As example, viable roots of Pueraria montana, can be wrongly attributed to other plants with similar roots (e.g., Dioscorea sp., Manihot esculenta Crantz, Maranta arundinacea L.); furthermore, seeds of the plant can be transported as contaminant of seeds for planting [32]. Alternanthera philoxeroides can be confused with A. sessilis (L.) R.Br. ex DC., which is consumed as a vegetable in Asia (Sri Lanka) and can be traded as food, even if this should be not a highly relevant pathway to the EU [76].

Lygodium japonicum is the only IAPUC that can be transported via the timber trade, even if this pathway is not considered highly likely (Figure 1).

2.5. Not Relevant Categories of Pathways for IAPUC

Two contaminant pathways related to agriculture were found to be irrelevant for the introduction or spread of IAPUC. These were “3.2 Contaminated bait” and “3.6 Contaminant on plants (excluding parasites and species transported by host and vector)”. The first refers to the unintentional or accidental introduction of contaminant species transported alongside bait species [19]; this is a peculiar and specific pathway and this result is not unexpected in that it has no relevance for IAPUC. Contrarily, it is quite surprising that the other pathway “3.6 Contaminant on plants” has been found to be not relevant for IAPUC. Its irrelevance can be related to a real lack of evidences or to the interpretation of the pathway itself. CBD includes in this category cases related to species introduced unintentionally as contaminants on plants or plant products transported through human related activities, but plants are those currently off the market, excluded from commercial nursery trade (e.g., plants being transported for non-commercial reasons or plants originally from the commercial nursery trade that have left the trade and been purchased by and used/planted by an end user) [19]. Already, Pergl et al. [13] pointed out that the interpretation of this pathway could be tricky. According to available guidelines, researchers found no match for this category with IAPUC. However, as it considers “out of market” movements, not easy to be tracked, the relevance of this pathway should not be completely excluded.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agronomy12020423

References

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100.

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1511–1534.

- Richardson, D.M.; Pysek, P.; Rejmanek, M.; Barbour, M.G.; Panetta, F.D.; West, C.J. Naturalization and invasion of alien plants: Concepts and definitions. Divers. Distrib. 2000, 6, 93–107.

- Essl, F.; Bacher, S.; Genovesi, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Jeschke, J.M.; Katsanevakis, S.; Kowarik, I.; Kühn, I.; Pyšek, P.; Rabitsch, W.; et al. Which Taxa Are Alien? Criteria, Applications, and Uncertainties. BioScience 2018, 68, 496–509.

- Bonnamour, A.; Gippet, J.M.W.; Bertelsmeier, C. Insect and plant invasions follow two waves of globalisation. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 2418–2426.

- Hulme, P.E. Unwelcome exchange: International trade as a direct and indirect driver of biological invasions worldwide. One Earth 2021, 4, 666–679.

- van Kleunen, M.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Pergl, J.; Winter, M.; Weber, E.; Kreft, H.; Weigelt, P.; Kartesz, J.; Nishino, M.; et al. Global exchange and accumulation of non-native plants. Nature 2015, 525, 100–103.

- Essl, F.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Booy, O.; Brundu, G.; Brunel, S.; Cardoso, A.-C.; Eschen, R.; Gallardo, B.; Galil, B.; et al. Crossing Frontiers in Tackling Pathways of Biological Invasions. BioScience 2015, 65, 769–782.

- Lambdon, P.W.; Lloret, F.; Hulme, P.E. How do introduction characteristics influence the invasion success of Mediterranean alien plants? Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 10, 143–159.

- van Kleunen, M.; Xu, X.; Yang, Q.; Maurel, N.; Zhang, Z.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Kreft, H.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P.; et al. Economic use of plants is key to their naturalization success. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3201.

- Guo, W.; van Kleunen, M.; Pierce, S.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Kreft, H.; Maurel, N.; Pergl, J.; Seebens, H.; Weigelt, P.; et al. Domestic gardens play a dominant role in selecting alien species with adaptive strategies that facilitate naturalization. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 628–639.

- Cossu, T.A.; Lozano, V.; Stuppy, W.; Brundu, G. Seed contaminants: An overlooked pathway for the introduction of non-native plants in Sardinia (Italy). Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2020, 154, 843–850.

- Pergl, J.; Brundu, G.; Harrower, C.A.; Cardoso, A.C.; Genovesi, P.; Katsanevakis, S.; Lozano, V.; Perglová, I.; Rabitsch, W.; Richards, G.; et al. Applying the Convention on Biological Diversity Pathway Classification to alien species in Europe. NeoBiota 2020, 62, 333–363.

- Montagnani, C.; Gentili, R.; Smith, M.; Guarino, M.F.; Citterio, S. The Worldwide Spread, Success, and Impact of Ragweed (Ambrosia spp.). Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2017, 36, 139–178.

- Haubrock, P.J.; Turbelin, A.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Novoa, A.; Taylor, N.G.; Angulo, E.; Ballesteros-Mejia, L.; Bodey, T.W.; Capinha, C.; Diagne, C.; et al. Economic costs of invasive alien species across Europe. NeoBiota 2021, 67, 153–190.

- Black, R.; Bartlett, D.M.F. Biosecurity frameworks for cross-border movement of invasive alien species. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 105, 113–119.

- Brundu, G.; Armeli Minicante, S.; Barni, E.; Bolpagni, R.; Caddeo, A.; Celesti-Grapow, L.; Cogoni, A.; Galasso, G.; Iiriti, G.; Lazzaro, L.; et al. Managing plant invasions using legislation tools: An analysis of the national and regional regulations for non-native plants in Italy. Ann. Bot. 2020, 10, 1–12.

- Paini, D.R.; Sheppard, A.W.; Cook, D.C.; De Barro, P.J.; Worner, S.P.; Thomas, M.B. Global Threat to Agriculture from Invasive Species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7575–7579.

- IUCN. Guidance for Interpretation of the CBD Categories of Pathways for the Introduction of Invasive Alien Species; Technical Note Prepared; IUCN for the European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; 80p.

- Ansong, M.; Pickering, C. Weed seeds on clothing: A global review. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 203–211.

- Rew, L.J.; Brummer, T.J.; Pollnac, F.W.; Larson, C.D.; Taylor, K.T.; Taper, M.L.; Fleming, J.D.; Balbach, H.E. Hitching a ride: Seed accrual rates on different types of vehicles. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 547–555.

- Rauschert, E.S.J.; Mortensen, D.A.; Bloser, S.M. Human-mediated dispersal via rural road maintenance can move invasive propagules. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 2047–2058.

- Lemke, A.; Buchholz, S.; Kowarik, I.; Starfinger, U.; von der Lippe, M. Interaction of traffic intensity and habitat features shape invasion dynamics of an invasive alien species (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) in a regional road network. NeoBiota 2021, 64, 155–175.

- IPPC ISPM 41 International Movement of Used Vehicles, Machinery and Equipment. Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/en/publications/84343/ (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Andropogon virginicus Included on the Union List. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/ec8eba63-7854-42c7-b558-01083e4cbf7a/TSSR%20Task%202018%20Andropogon%20virginicus.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- EPPO. Pest Risk Analysis for Lygodium japonicum; EPPO: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/LYFJA/documents (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Hutchinson, J.T.; Langeland, K.A. Potential spread of Lygodium microphyllum spores by herbicide applicators. Wildland Weeds 2006, 9, 13–15.

- Lott, M.S.; Volin, J.C.; Pemberton, R.W.; Austin, D.F. The reproductive biology of the invasive ferns Lygodium microphyllum and L. japonicum (Schizaeaceae): Implications for invasive potential. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 1144–1152.

- Helsen, K.; Diekmann, M.; Decocq, G.; De Pauw, K.; Govaert, S.; Graae, B.J.; Hagenblad, J.; Liira, J.; Orczewska, A.; Sanczuk, P.; et al. Biological flora of Central Europe: Impatiens glandulifera Royle. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2021, 50, 125609.

- Follak, S.; Bakacsy, L.; Essl, F.; Hochfellner, L.; Lapin, K.; Schwarz, M.; Tokarska-Guzik, B.; Wołkowycki, D. Monograph of invasive plants in Europe N°6: Asclepias syriaca L. Bot. Lett. 2021, 168, 1–30.

- Kartzinel, T.R.; Hamrick, J.L.; Wang, C.; Bowsher, A.W.; Quigley, B.G.P. Heterogeneity of Clonal Patterns among Patches of Kudzu, Pueraria montana var. lobata, an Invasive Plant. Ann. Bot. 2015, 116, 739–750.

- Bravo, M.A. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Included on the Union List: Pueraria Montana . Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/4cd6cb36-b0f1-4db4-915e-65cd29067f49/library/60e6c8b4-abc9-470c-b52e-1903a5d4d3de/details (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- von der Lippe, M.; Bullock, J.M.; Kowarik, I.; Knopp, T.; Wichmann, M. Human-Mediated Dispersal of Seeds by the Airflow of Vehicles. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52733.

- Säumel, I.; Kowarik, I. Propagule morphology and river characteristics shape secondary water dispersal in tree species. Plant Ecol. 2013, 214, 1257–1272.

- Danin, A. The inclusion of adventive plants in the second edition of Flora Palaestina. Willdenowia 2000, 30, 305–314.

- Brundu, G.; Lozano, V.; Branquart, E. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Considered for Inclusion on the Union List: Acacia Saligna. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/7685ce4c-b6c4-4fd7-96b6-0c360ffbffa4/TSSR%20Task%202018%20Acacia%20saligna.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Heidbüchel, P.; Hussner, A. Falling into pieces: In situ fragmentation rates of submerged aquatic plants and the influence of discharge in lowland streams. Aquat. Bot. 2020, 160, 103164.

- Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Barcheri, G.; Ballerini, C.; Cauzzi, P.; Guzzon, F. Gymnocoronis spilanthoides (Asteraceae, Eupatorieae), a new naturalized and potentially invasive aquatic alien in S Europe. Willdenowia 2016, 46, 265–273.

- EPPO. Lysichiton americanus. EPPO Bull. 2006, 36, 7–9.

- Pasiecznik, N. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Considered for Inclusion on the Union List: Prosopis juliflora. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/30b8a728-06b9-401f-a940-9531636e8fe9/TSSR%20Task%202018%20Prosopis%20juliflora.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Coetzee, J.; Hill, M. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Included on the Union List—Pontederia Crassipes . Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/4cd6cb36-b0f1-4db4-915e-65cd29067f49/library/2aa973a2-e6a6-4cb0-bf1d-6c9c8bbd7f92/details?download=true (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Smith, E.R.C.; Bennion, H.; Sayer, C.D.; Aldridge, D.C.; Owen, M. Recreational angling as a pathway for invasive non-native species spread: Awareness of biosecurity and the risk of long distance movement into Great Britain. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 1135–1159.

- Lukács, K.; Valkó, O. Human-vectored seed dispersal as a threat to protected areas: Prevention, mitigation and policy. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 31, e01851.

- EPPO. Heracleum mantegazzianum, Heracleum sosnowskyi and Heracleum persicum. EPPO Bull. 2009, 39, 489–499.

- Smith, K.; Kraaij, T. Research note: Trail runners as agents of alien plant introduction into protected areas. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100315.

- McNeill, M.; Phillips, C.; Young, S.; Shah, F.; Aalders, L.; Bell, N.; Gerard, E.; Littlejohn, R. Transportation of nonindigenous species via soil on international aircraft passengers’ footwear. Biol. Invasions 2011, 13, 2799–2815.

- Gentili, R.; Casati, E.; Ferrario, A.; Monti, A.; Montagnani, C.; Caronni, S.; Citterio, S. Vegetation cover and biodiversity levels are driven by backfilling material in quarry restoration. CATENA 2020, 195, 104839.

- Strydom, M.; Veldtman, R.; Ngwenya, M.Z.; Esler, K.J. Invasive Australian Acacia seed banks: Size and relationship with stem diameter in the presence of gall-forming biological control agents. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181763.

- Richardson, D.M.; Kluge, R.L. Seed banks of invasive Australian Acacia species in South Africa: Role in invasiveness and options for management. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 10, 161–177.

- Gioria, M.; Osborne, B.A. Biological Flora of the British Isles: Gunnera tinctoria. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 243–264.

- Skálová, H.; Moravcová, L.; Čuda, J.; Pyšek, P. Seed-bank dynamics of native and invasive Impatiens species during a five-year field experiment under various environmental conditions. NeoBiota 2019, 95, 75–95.

- Čuda, J.; Alov, H.S.K.; Sek, P.P.Y. Spread of Impatiens glandulifera from riparian habitats to forests and its associated impacts: Insights from a new invasion. Weed Res. 2020, 60, 8–15.

- Kowarik, I.; Säumel, I. Biological flora of central Europe: Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007, 8, 207–237.

- Sladonja, B.; Sušek, M.; Guillermic, J. Review on Invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle) Conflicting Values: Assessment of Its Ecosystem Services and Potential Biological Threat. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1009–1034.

- Kowarik, I.; Säumel, I. Water dispersal as an additional pathway to invasions by the primarily wind-dispersed tree Ailanthus altissima. Plant Ecol. 2008, 198, 241–252.

- IUCN. Legal Provisions on Soil Import. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/96fbf64a-c3e8-49ab-bb5f-efb6cdc16e85/Legal%20provisions%20on%20soil%20import.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- EPPO. Andropogon virginicus L. EPPO Bull. 2019, 49, 61–66.

- EPPO. Ehrharta calycina Sm. EPPO Bull. 2019, 49, 55–60.

- EPPO. Microstegium vimineum (Trin.) A. Camus. EPPO Bull. 2016, 46, 14–19.

- Friedel, M.H. Uninvited guests: How some weeds of arid Australia arrived as stowaways and became widespread. In Proceedings of the 19th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference, Port Augusta, Australia, 25–28 September 2017; Australian Rangeland Society: Port Augusta, Australia; pp. 1–3.

- EPPO. Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb. EPPO Bull. 2016, 46, 8–13.

- Bohn, K.K. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Considered for Inclusion on the Union List: Lygodium Japonicum. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/26860e47-a81c-4b09-a127-201df2c1bd66/TSSR%20Task%202018%20Lygodium%20japonicum.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Tewksbury, L. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Included on the Union List—Persicaria perfoliata. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/4cd6cb36-b0f1-4db4-915e-65cd29067f49/library/092330a5-62d0-48b8-b12e-bc8424f33fbb/details (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Robert, H.; Lafontaine, R.M.; Beudels-Jamar, R.C.; Delsinne, T. Risk Analysis of the Water Pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (L.F.; 1781)—Risk Analysis Report of Non-Native Organisms in Belgium; Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences for the Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; 59p.

- Hussner, A. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Included on the Union List: Elodea nuttallii; Technical Note; IUCN for the European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Hussner, A. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to the Species Included on the Union list—Lagarosiphon major. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/4cd6cb36-b0f1-4db4-915e-65cd29067f49/library/f01f7025-1a53-4dc2-8d7b-760e1e00345b/details?download=true (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Oele, D.L.; Wagner, K.I.; Mikulyuk, A.; Seeley-Schreck, C.; Hauxwell, J.A. Effecting compliance with invasive species regulations through outreach and education of live plant retailers. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 2707–2716.

- EPPO. Pest Risk Analysis for Ehrharta calycina; EPPO: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://pra.eppo.int/pra/3aca29b4-9c25-4b25-8fad-66de6d494eba (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- EPPO. Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC. EPPO Bull. 2019, 49, 290–297.

- USDA. Weed Risk Assessment for Gymnocoronis spilanthoides (D. Don ex Hook. & Arn.) DC. (Asteraceae)—Senegal Tea Plant; United States Department of Agriculture: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2017.

- EPPO. Parthenium hysterophorus L. Asteraceae—Parthenium Weed. EPPO Bull. 2014, 44, 474–478.

- Panetta, F.D. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to Species Included on the Union List: Parthenium hysterophorus. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/4cd6cb36-b0f1-4db4-915e-65cd29067f49/library/ab5c3d3a-4978-46da-b416-3efb44b24f6d/details?download=true (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- EPPO. PM 9/9 (2) Heracleum mantegazzianum, H. sosnowskyi and H. persicum. EPPO Bull. 2020, 50, 515–524.

- USDA. Weed Risk Assessment for Cortaderia jubata (Lemoine ex Carrière) Stapf (Poaceae)—Jubata Grass; United States Department of Agriculture: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2014.

- Newman, J.; Duenas, M.A. Information on Measures and Related Costs in Relation to the Species Included on the Union List: Myriophyllum heterophyllum and Myriophyllum aquaticum. Technical Note Prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/4cd6cb36-b0f1-4db4-915e-65cd29067f49/library/6926c6f9-9c87-4da0-a507-10186e14ed8a/details?download=true (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- EPPO. Pest Risk Analysis for Alternanthera philoxeroides; EPPO: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: http://www.eppo.int/QUARANTINE/Pest_Risk_Analysis/PRA_intro.htm (accessed on 20 December 2021).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!